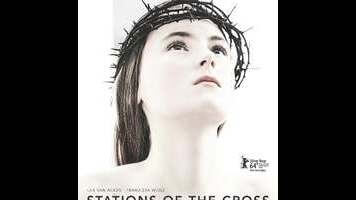

Adopting the basic structure of a passion play, Stations Of The Cross depicts a few eventful days in the life of this new “warrior for Christ,” studying the toll a serious commitment to the faith takes on her body and mind. Maria, played with trembling fervor by newcomer Lea Van Acken, comes from a family of ultra-devout Catholics. (They belong to the Society Of Saint Pius X, which is strict even by Catholic standards.) Maria is all of 14, but can’t shake the conviction that she should literally give her life to God—a sacrifice she hopes will cure her little brother of the muteness he’s been afflicted with since birth. Intense commitment aside, temptations surround her: At the library, she meets Christian (Moritz Knapp), a young fellow believer who invites her to join his church choir and sing gospel and soul songs—the devil’s music, according to her domineering, fanatical mother (Franziska Weisz). But Christian’s intentions seem, well, fairly Christian. And when Maria confesses her attraction to the boy, it’s an almost comically chaste fantasy: the desire to have his arm around her while they go to church together.

Revisiting an aesthetic strategy he introduced in his first feature, Neun Szenen, German director Dietrich Brüggemann tells Maria’s story in 14 single-shot scenes, most of them filmed from a fixed camera angle and all of them named—per the film’s title—for something that happened to Christ en route to crucifixion. Some of these chapter headings will make less sense than others, at least to secular viewers: While “Jesus’ clothes are taken away” is a perfectly appropriate way to describe the scene where our sick heroine undresses at the doctor’s office, several “stations” of Maria’s ordeal relate more obliquely to their scriptural inspiration. The larger point here seems to be that fundamentalism turns faith into a burden; when you deprive yourself of everything, religion can break your spirit instead of raising it. That may sound like a pretty clear anti-theological slant, but Brüggemann—working with his sister and regular screenwriter, Anna—flirts more with ambivalence, especially in a closing passage that raises serious questions about the ultimate value of Maria’s increasingly extreme acts of devotion. (The final image seems designed to divide interpretation down lines of belief or a lack thereof.)

Formally, Stations Of The Cross is a rigorous achievement; there’s a purity, cinematic if not spiritual, to the way Brüggemann carefully composes each static shot, as though they all really were paintings to be arranged in succession along a line of pews. It’s less successful on a dramatic level: Again, only the most passing knowledge of the Passion is required to predict Maria’s eventual fate, and the film is as rigidly controlled, and often as severe, as her life under the word. Intentionally schematic, Stations benefits immensely from little cracks in its design: tender moments shared between Maria and the French exchange student (Lucie Aron) staying with her family; one of Maria’s siblings running wild through the back of a meticulously framed shot, a rolled-up scrap of paper his telescope to the heavens; and the drops of dry comedy that arrive periodically, like shows of benevolence from the creative power above.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.