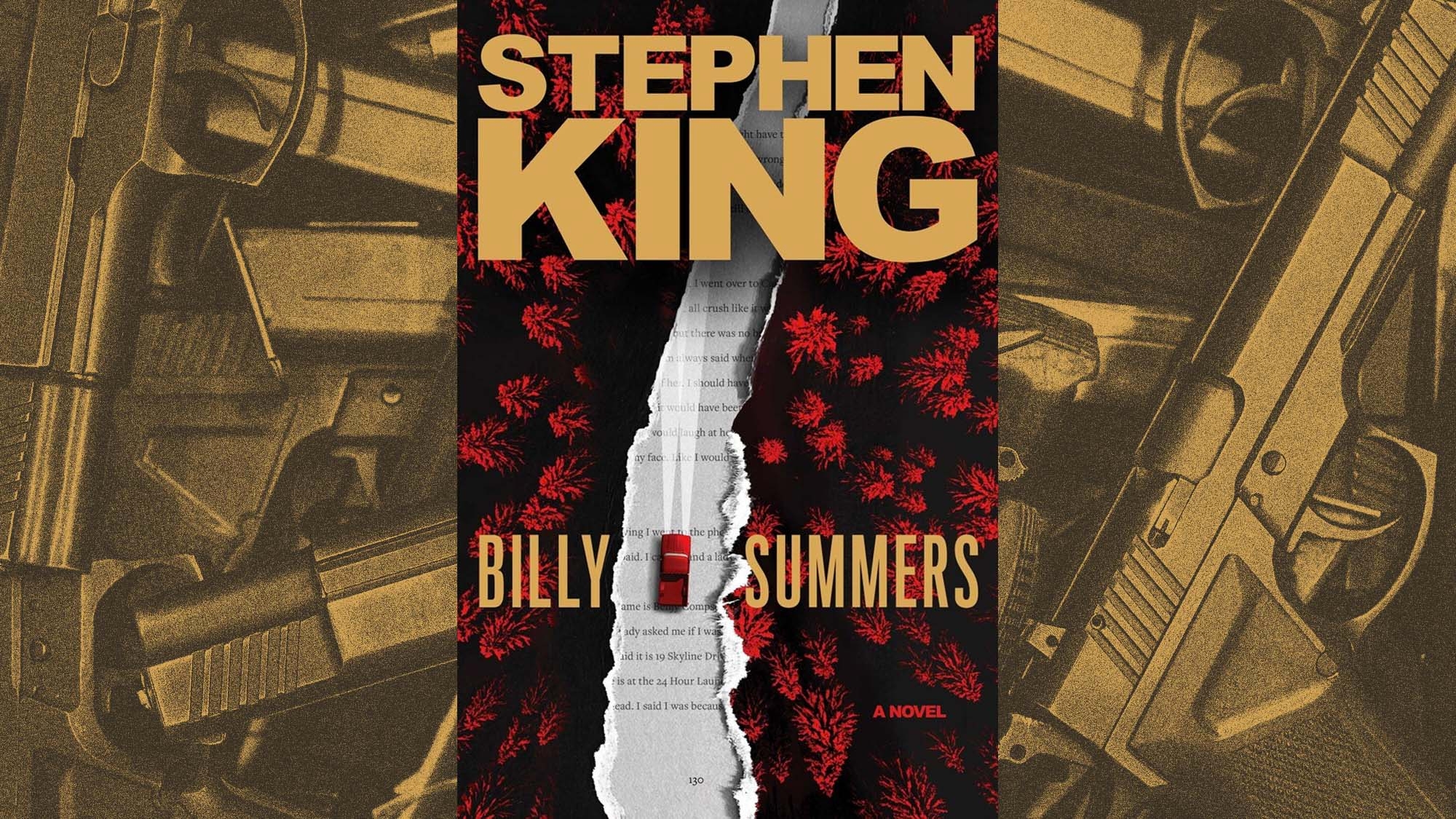

Stephen King evokes John Wick and pandemic anxiety in the tense, fractured Billy Summers

The first half of King’s new crime novel is some of his best work in years. The second half is a different story.

The final page of Billy Summers—Stephen King’s latest effort to master pulp crime fiction just as he tamed horror several decades ago—includes, like many of King’s books, a note saying when he wrote it. In most of King’s novels, this addendum serves as little more than a cheery footnote, a reminder of the hard work and the sheer amount of time that must be poured into the author’s brick-heavy tomes to bring them to life. But in Billy Summers, those dates arrive with a meaning that no one could have anticipated when King first sat down to craft his story of a hitman with a heart of gold: June 12, 2019 – July 3, 2020.

To be clear, Billy Summers is not a pandemic novel, at least not in the traditional sense. Outside of a few allusions to the COVID-19 lockdowns, King resists the urge to import details directly from a reality that has sometimes felt cribbed from the pages of his most famous works. But the steadily growing cabin fever is nevertheless inescapable as one dives deeper into the book, and a first act of stunning formal control gives way to a second half that is frequently unfocused, lurid, and, at times, clichéd. All of which builds to a climax that seems to pull from the darkest recesses of home-brewed Twitter and cable news paranoia; it’s wish fulfillment for those living in a world where the rich and powerful orchestrate acts of monstrous evil, while we’re all stuck at home, brokenly clicking along. The action then settles, almost miraculously, into an epilogue that brings the book’s best qualities back to the forefront.

But first: That opening half, which sees its title contract killer shacking up in a nondescript Midwestern city, waiting several months for his next target to be delivered to a nearby courthouse. In the meantime, the Iraq vet-turned-freelance-sniper must blend in with the locals, a setup King uses to get the wheels spinning on a delicious engine of tension. By the time the date of the hit arrives, our uber-competent undercover anti-hero is running something like five different identities in an effort to keep everyone—his neighbors, his employees, himself—in the dark about what’s actually going on. The most prominent of these is also the one that tips the book into more recognizable King territory, as Billy’s employers (having bought into his persona as a slow-witted murder-savant) mockingly set him up as a first-time novelist to explain his extended stay in town.

If Billy Summers has a thesis—beyond the burbling morass of vengeance fantasies that threaten to transform the second half into something akin to Stephen King’s Death Wish—it’s in the sequences that dive into Billy’s attempts to turn his cover gig into a real one and filter his life story into prose. King has written so many author-protagonists over the years that it’s tipped over from a running joke into simply being part of the background radiation of his oeuvre. But he’s rarely put this much time and energy into depicting the actual cathartic work of the job, up to and including drafting whole chapters of Billy’s writing as he processes his abusive childhood and military service to untangle the web of identities he’s crafted around himself. The rapture with which Billy realizes he can finally peek out from behind the masks and speak in his own voice (if only to himself) could have been corny in another book, but in King’s hands, it comes off as infectiously genuine. In addition to those loftier ideas, these excerpts are also a chance for King to engage in a bit of metafictional gamesmanship, crafting text that reads like the work of a gifted beginner, distinct from the more familiar tone used in the rest of the book.

At least in the early going, the bulk of Billy Summers is a delightfully tense crime thriller, tracking the protagonist’s efforts to pull “one last job”—the character, an aggressive consumer of literary fiction, notes the trope himself. Ostensibly light on incident, Billy’s preparations highlight King’s sharp skills for observation—sizing up the people in his orbit for how they might help or pose a danger to his schemes—and begin to unlock some of the traumas that drove him to kill for cash. The fact that those deep-seated motives seem to have been largely pulled from The Big Book Of Professional Murderers Who Are Also Good, Sensitive Guys, We Swear, can probably be chalked up as much to the genre as King’s actual plotting. The result, despite its surface familiarity (it’s wild how much of Billy’s story tracks with HBO’s Barry, for example, to say nothing of the outright John Wick reference that pops up), is somehow both hard-boiled and human, and on par with much of King’s best work.

All of this holds true until the halfway point, when, with the pull of a trigger, King jettisons huge swaths of the tension that made Billy Summers such a compulsive, memorable read. What replaces it is a sort of surreal vigilante road trip tale, shot through with sexual violence and revenge, which adds a seemingly unintentional queasy element to the book’s central relationships. The complicated layers of identity fall away, and what we’re left with verges on the simplicity of a morality play.

It would be reductive to assume that this portion of Billy Summers (which begins with Billy locking himself away for weeks at a time and even features him bingeing NBC’s The Blacklist) was written strictly post-outbreak, and the rest before. But as the singular focus of the first act morphs into a sprawling revenge thriller that sees King invent ever-more-awful (human) monsters for his hero to hunt, it’s hard not to feel like a sheer dividing line was crossed somewhere. Certainly, it’s strange that the portions of the book in which its hero fritters away his days playing Monopoly with local kids are far more compelling than those in which he roams the country, executing crime lords and rapists. Given King’s experimentation with serialization over the years, it’s hard not to wish that the two stories—and that is, ultimately, what this feels like—could have had more separation between them, if only so the second half didn’t suffer so much by comparison.

It’s the writing that saves Billy Summers—both the prose itself and the depiction of the act. Together, they give the book the lifeline it needs as its ripped-from-the-headlines ending looms. Even in the most hoary of crime scenarios, King can still build tidal waves of tension from the smallest deviation from plan, sending Constant Readers plunging deep into the flop-sweat insecurities of his heroes as they watch a situation potentially spiral out of control. In situating Billy’s atonement in communication and creation, not violence, King manages to find a space for redemption that might otherwise have rung hollow. For a book whose only supernatural element is the occasional looming ruin of the distant Overlook Hotel—where another King writer stand-in once fared far more poorly with his isolation and “gifts”—Billy Summers is winningly optimistic about the life of the creative mind. More than almost any other King book in recent memory, it’s a product of its time, but not a victim of it.

Author photo: Shane Leonard