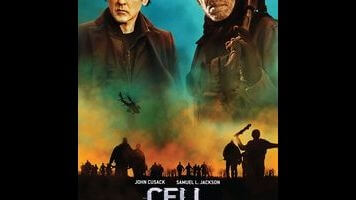

About those names: Cell may function finest as the 1408 reunion no one asked for, with John Cusack and Samuel L. Jackson again joining forces to headline another adaptation of lesser King. Neither star is giving it their all—the former sometimes looks more inconvenienced than terrified—but neither are they quite phoning it in (har har), and their presence provides an air of professionalism that’s otherwise in short supply. Cusack plays Clay Riddell, another of King’s surrogate everymen, in this case a graphic novelist returning from a work trip at the exact moment that every operational cellular device begins broadcasting a rage-inducing signal. Escaping a bloody mob scene at the airport, he ends up allied with a cool-headed stranger (Samuel L. Jackson) and a frazzled teenager (Isabelle Fuhrman); determined to make it to his son and estranged wife in Vermont, Clay leads this makeshift family on an episodic road trip, crossing New England on foot and encountering various survivors along the way.

King set Cell’s harrowing early scenes in Boston, but the movie was filmed in and around Atlanta, and the first signs of budgetary restriction arrive during the opening set-piece, relocated from Boston Common to a nondescript terminal. It’s sloppy instead of chaotic, Williams capturing the gory details—people thrown to their death from balconies; a man munching on his dog—in erratic, shaky-cam close-up and with not nearly enough extras to convincingly convey the pandemonium, before punctuating the carnage with a plane crash straight out of a Syfy original movie. The effects in general, from a series of digital explosions to a climactic horde of the infected, betray limited resources. Then again, Williams largely botches most of the small-scale skirmishes too, getting the least out of backyard gunfights. His decision to run the credits over oversized black bars, effectively obscuring the first few shots of his own film, implies a troubling disinterest in imagery.

Cell picks up some once Clay and his posse hit the road, and the film shifts to the durable dramatic scenario of desperate people bouncing from shelter to shelter, always on the move but never safe. King’s conception of the zombies (or “Phoners,” as they’re amusingly nicknamed) is novel enough: Sprinting with the breakneck speed of the 28 Days Later variety, they move in hive-mind swarms, all on the same “network,” and communicate by emitting an atonal blare of modem noise. But the film cuts corners in ways unrelated to budget. Despite all the downtime spent squatting in darkened buildings, none of the characters ever gain much nuance or dimension—they talk, but say little of substance. Nor does the film properly communicate the breakdown of society, which seems to happen in the space of about an hour and which the characters accept immediately.

Identifying King’s tics and tropes—vague psychic links; an author’s work becoming real; bonding over classic rock—will provide modest pleasures, at least for those who have binged on his prose. Cell is one the novelist’s hodgepodges of familiar ideas, and there’s fun in seeing how it blends elements from Romero’s Dead series, Invasion Of The Body Snatchers (the 1978 version, with the inhuman screaming), and Nightmare On Elm Street (note the deformed dream invader) with King’s own, earlier post-apocalyptic milestone, The Stand. But reading the book would offer the same mélange, minus the subpar effects and careless staging. On screen, Cell is diverting enough, provided one can forgive its chintz factor and just key into its Walking Dead moodiness. But it’s not a good sign when a movie leaves you wishing that Eli Roth had directed it instead.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.