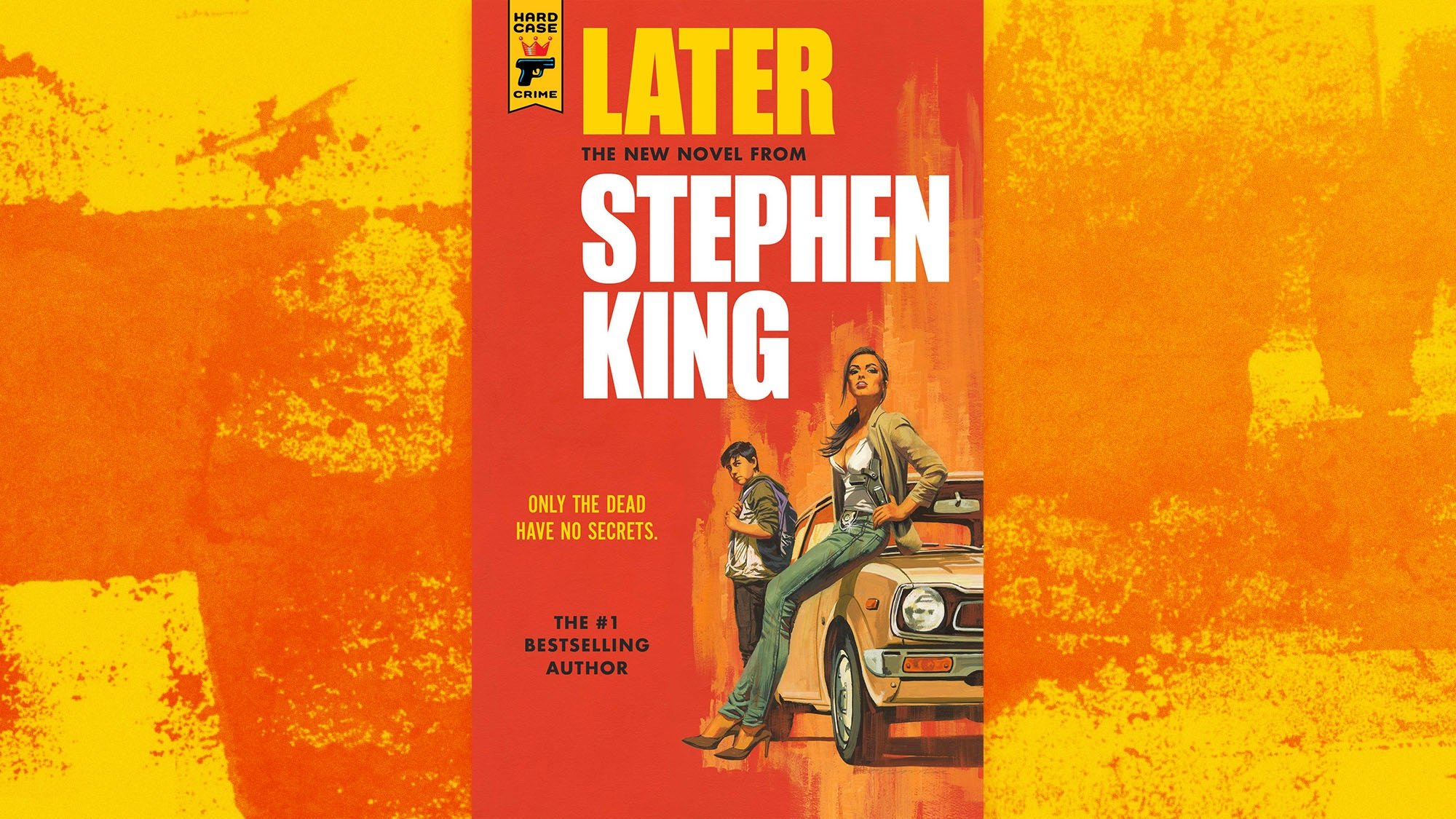

If Hard Case Crime is devoted to publishing “the best in hard-boiled crime fiction,” then why did it put out Later? Because Stephen King wrote it, dummy. It’s the genre legend’s third release via the imprint, and easily the most out of step with the publisher’s central thesis. Is there crime? Sure, but Later isn’t a crime novel, let alone a hard-boiled one. There’s no antihero, no femme fatale, no cynicism, no focus on institutionalized social corruption. In short, there’s nothing all that pulpy about it. That’s not a bad thing, of course; it’s just not the grimy, scintillating read its tawdry cover suggests.

Dead people aren’t scary, though. They’re disinterested. And they fade into the ether after a few hours. And, this is the big one, they’re seemingly incapable of telling lies. These are the “rules,” as Jamie’s come to understand them, and they prove mighty useful for those in his orbit, including his single mother, Tia, a publisher hobbled by the 2008 financial crisis. When her company’s star author croaks just a few chapters into his new novel, for instance, it’s on Jamie to suss the plot from his lingering spirit. It’s a clever spin on an old trope, and King mines morbid humor from Jamie’s own lack of interest in serving as ghost translator. But it isn’t long before we’re reminded that rules were made to be broken. There’s more in the stars than ghosts and dead people.

And there’s more in Later than its trim 260 pages might suggest. King, who tends to stretch stories out like taffy, crowds Jamie’s encounters with the undead (and their “gooshy” wounds) with a mad bomber, a shady detective, and a sordid drug lord. It’s in those scenes, stuffed as they are with pills and guns and ball gags, that King attempts to hard-boil his story, but there’s nothing here that hasn’t been reheated a dozen times over on cable—aside from how Jamie’s link to the dead affects everything. And while Later’s vision of the dead is plenty creepy on its own, it takes on added resonance when King weaves it in with the events of one of his most-loved novels, one familiar to even his most casual readers. It’s inessential, the twist, but plenty interesting in the larger realm of King’s oeuvre, which the author’s knotted into a literary universe all his own. Spiritually, consider it akin to Night Shift’s “One For The Road” or the titular tale from last year’s If It Bleeds. Narratively, however, Later recalls recent King novellas like Gwendy’s Button Box and Mr. Harrigan’s Phone, simple stories that wrap a complex moral choice in a character’s supernatural ability.

Later also shares some DNA with its Hard Case predecessor, 2013’s amusement park mystery Joyland, though primarily in voice and structure. Both feature amiable narrators sorting through the traumas of youth as adults, and both are preoccupied by a special lady in their lives. For Joyland’s Devin, it’s his first love; for Jamie, it’s Tia. Later’s big, gooshy heart beats for her and Jamie’s bond, which is sweet, offbeat, and not without its secrets. King has always had a knack for funneling the complicated inner realities of adults through the eyes of children, and some of Later’s most affecting passages find Jamie piecing together his mother’s struggles via empty wine bottles and scraps of overheard chatter. Kids have a way of figuring out what their parents won’t tell them, for better or worse.

For many a King protagonist, flexing your otherworldly ability means inviting spirits from that other world into your own. That’s true both literally and figuratively in Later, which posits that unfettered access to the truth is both a blessing and a curse. If sometimes dead is better, to quote an old King standard, then so too is ignorance.

Author photo: Shane Leonard

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.