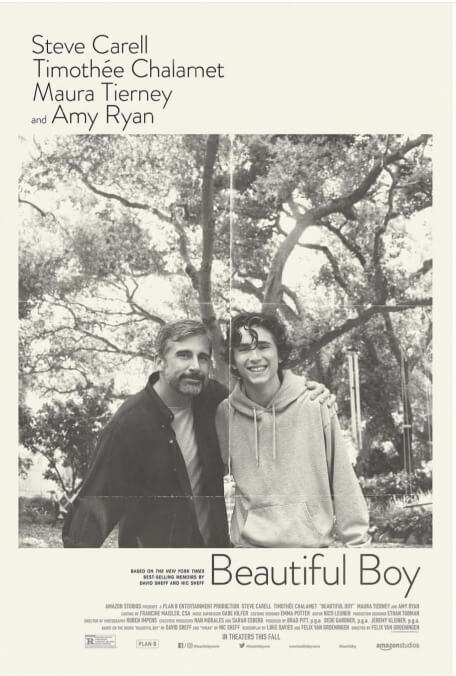

Steve Carell and Timothée Chalamet anchor the father-son addiction drama Beautiful Boy

“Relapse is a part of recovery.” That’s what the specialist at the clinic tells David Sheff (Steve Carell) the first time his teenage son, Nic (Timothée Chalamet), runs out on rehab. To this distraught parent, it sounds like a canned platitude—and maybe it is, at least in the sense that they dust it off every time someone under their care falls off the wagon. But David will learn to see the hard truth in the phrase, probably around the second time that Nic, having fought his way again to sobriety, finds his way back to crystal meth. Beautiful Boy is all about the cycle of addiction: the denial, the lies, the good highs, the bad highs, the pleading for help, the going clean, the itch, the backslide, rinse and repeat. But it’s also about another cycle, experienced in parallel by the loved ones. They, too, can get locked in a closed loop, their own recurrent pattern of hope and despair, broken only when the abuser really kicks the habit—or, sadly, when those in the abuser’s life come to believe that they never will.

This isn’t just a true story. It’s two of them in one: different angles on the same family trauma, tied together into a helix. Director Felix Van Groeningen and his cowriter, Luke Davies, have adapted a pair of memoirs—one by the real David Sheff, sharing the hopelessness he felt standing on the sidelines of a battle against dependency, and the other by the real Nic Sheff, offering his firsthand account of what methamphetamine does to your mind, body, and relationships. Beautiful Boy communicates the father’s ordeal a little more clearly than the son’s; it’s hyper-specific on David’s cocktail of evolving emotions—panic, anger, guilt, horror—and a little vaguer on Nic’s. But the split point of view, coupled with a wealth of ripped-from-experience details, is a welcome approach to a subject so frequently explored that you’re lucky to get a drop of fresh insight out of it.

After one of those needless start-in-the-middle prologues, Beautiful Boy rewinds back a year to the start of the family’s crisis (or, rather, to when Nic’s crisis became everyone’s to shoulder). David, a San Francisco-based writer, is sick with worry for his 18-year-old son, who’s been missing for two days. When Nic does return, he’s clearly coming down hard from something; though he insists it was a one-time mistake, David convinces him to commit to a month-long rehabilitation program. This is the beginning of a grueling pattern. From here, the film traces his on-off war with the disease: trading the supervision of his father and stepmother, Karen (Maura Tierney), for that of his mother, Vicki (Amy Ryan), in Los Angeles; disappearing for weeks on end; swearing off drugs for long stretches, only to be sucked back into the vice grip of his vice.

Van Groeningen, a Belgian filmmaker whose breakthrough, The Broken Circle Breakdown, also concerned a family rocked by tragedy, pulls us forward through the weeks, months, and years, flowing from one grueling anecdote to the next. He also leaps backwards in time to explore the foundation of the father-son relationship (It’s Jack Dylan Grazer, who plays the preteen Nic, is a dead ringer for Chalamat), and to get us into David’s agonizing self-reflection. Did he say the wrong thing when they talked about drugs? Is there something he could have done to prevent this? At times, Van Groeningen’s churning, pop-and-rock-driven montage threatens to simplify the Sheffs’ pain: He turns Nic’s first semester of college into a glorified Sigur Rós music video—needle drop has a dual meaning here—and there are perhaps one too many shots of Carrell, in what may be his least comic turn ever, staring pensively into the middle distance. But the nonlinear structure can’t abstract the animated, wrenchingly physical power of Chalamet’s acting. If anything, it layers the Call Me By Your Name star’s performance, constantly contrasting his lows—tweaking outbursts, crestfallen spirals of self-loathing after a setback—with what it looks like when Nic is centered and whole and clean.

For as much as Van Groeningen may have pulled from both of his mirrored source materials, for as deep as Chalamet digs into his character’s skirmish with own urges, Beautiful Boy holds us outside of his struggle. We’re made to understand David, to see how some of the man’s anguish is a curdled form of shame, what Nic correctly identifies as embarrassment over how his son failed to live up to his and the world’s expectations. (“This isn’t who we are,” David blurts out in a moment of selfish frustration.) But the movie can’t quite crack the nagging discontent that sent Nic reaching for artificial euphoria in the first place. That imbalance could be by design, of course. Maybe we’re meant to see Nic the way David does, to just observe his self-destructive actions and wonder what’s really going on in his head. Either way, there’s a real integrity to how this perceptive addiction drama avoids easy arcs and simple resolutions, right up until an ending that makes you wonder if you’re seeing the final disruption of a cruel cycle or just the calm before it begins its rotation anew.