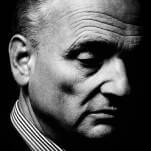

The book’s title is borrowed from the songbook of one of Earle’s musical heroes, Hank Williams—but Earle goes one further, casting Williams as a character in the novel. Or rather, Williams’ ghost: Set in Texas in 1963, a decade after the country great mysteriously died at age 29, I’ll Never Get Out follows Williams’ spirit as it haunts the fictional Doc Ebersole, a middle-aged junkie who performs abortions in San Antonio’s seedy South Presa Strip. Ostensibly based on P.H. Cardwell, a real-life physician who facilitated Williams’ morphine habit, Doc can see and hear Williams’ ghost only when he’s high—and their drug-aided relationship is a contentious one riddled with guilt and the weight of Williams’ burgeoning legend.

Doc himself acknowledges that his haunting may be all in his head—that is, until the ghost is seen by Graciela, a teenage illegal from Mexico who shacks up in Doc’s boarding-house room after being abandoned by her boyfriend post-abortion. But that isn’t Graciela’s only supernatural ability: After she cuts her wrist on a fence while waving at Jacqueline Kennedy the day before her husband’s assassination in Dallas, the wound fails to close. Thus stigmatized, she begins to heal the pushers and prostitutes of South Presa—which brings her to the attention of vicious Irishman Paddy Killen, a local priest and former pugilist who has his own reasons for seeing Graciela made a saint.

While Earle draws Doc in evocative detail, he paints most of the rest of his characters in broad strokes and hands them painfully on-the-nose dialogue. In particular, Graciela feels more like a prop than a person. And his juggling of the specters of Williams and Kennedy starts to fall apart halfway through the book, as does the plot; after an absorbing buildup full of eye-gouging imagery and lyrically bleak insights into junkie logic, the story comes off the rails and rambles toward a ramshackle conclusion. And while Earle ultimately fails to make his mash-up of myth-spinning and magic realism cohere into anything more solid than Williams’ ghost, the attempt is shot through with bursts of dirty brilliance.