Splitting the difference between Frank Capra and John Le Carré, Steven Spielberg’s Bridge Of Spies mounts an ode to the little guy of American idealism within the realpolitik of the Cold War. Textured with ink-blot shadows, ripples of snow and rain, and pinpricks of bright primary color—a neon sign seeping red into a puddle, a bar humming blue—it’s one of the most handsome movies of Spielberg’s latter-day phase, and possibly the most eloquent. Inspired by the real-life exploits of attorney-turned-international-negotiator James B. Donovan, Bridge Of Spies turns a secret prisoner exchange between the CIA and the KGB into a tense and often disarmingly funny cat-and-mouse game, in which an insurance lawyer with a bad cold finds himself having to outwit both sides in the name of a democratic value.

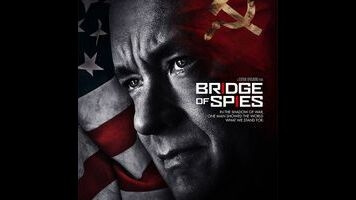

Largely set in an early ’60s East Berlin that is equal parts theater of the absurd and painter’s palette smeared with shades of gray, the movie stars Tom Hanks as Donovan, who is drafted as the pro-bono defense attorney for KGB agent Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance, superb), and then finds himself representing the CIA when it comes time to trade Abel for downed U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers (Austin Stowell). Donovan, however, also wants to secure the release of an economics student who found himself on the wrong side of the newly built Berlin Wall—an exchange complicated by the fact that said student has zero value for American counterintelligence, and is being held by the East German authorities rather than the Soviets.

Co-written by Joel and Ethan Coen, Bridge Of Spies often skews toward satire, lampooning everything from anti-Communist groupthink and nuclear hysteria to the Eastern Bloc’s bizarre mix of pageantry and secrecy, which finds the sneezing, coughing hero having to maneuver his way around fatuous functionaries and inept impostors. (A revealing reference: Looking for a phone booth in West Berlin, Donovan finds himself in front of a theater that’s playing Billy Wilder’s fast-paced Cold War send-up One, Two, Three.) And yet, one would be hard-pressed to classify the movie as a comedy.

The premise all but invites a run-down of Spielbergisms: the mission-of-principle of Saving Private Ryan meets the quick-footed mid-century intrigue of Catch Me If You Can in Lincoln’s smoke-filled, curtains-drawn back rooms of government. (It’s no coincidence that two of those films also star Hanks, who is cast here as a figure of fundamental gosh-darned decency who would seem unlikely if he weren’t played by Tom Hanks.) What it is, though, is the most purely expressive workout of a theme Spielberg has tackled before, in Lincoln and the earlier Amistad: the moment when the misty-eyed principles of American democracy get measured against its laws and policies.

It’s been a given for going on four decades now that Spielberg is about as confident a director as this country’s likely to produce. Even when he gets sappy—which he has more and more since aging his way into the pantheon of so-called great American directors—the one-time blockbuster upstart still directs the heck out of everything, with a command of the nuts and bolts of film grammar that’s easy to take for granted, but which still puts him in a different category from just about everyone working in Hollywood today. (Even something as corny as The Terminal has a sense of finesse.) Bridge Of Spies is the director’s most straightforward genre piece since War Of The Worlds; not coincidentally, it’s also his best film in a decade.

Shooting in roomy anamorphic widescreen and making only the most sparing use of Thomas Newman’s score, Spielberg renders the negotiation as a conflict of colors and forms, which comes to a head at the snow-covered Glienicke Bridge—the notorious prisoner exchange point connecting Potsdam with West Berlin, framed here as a corridor of white between two masses of shadow. Bridge Of Spies is full of thick, broad strokes: the courtroom rising at Abel’s trial cuts straight into children reciting the Pledge Of Allegiance before being shown an atomic scare film; a failed escape at the Berlin Wall gets a delayed rhyme in a shot of children gamely leaping chain-link fences in Brooklyn, and so on and so forth.

But even when it errs on the side of the heavy-handed, Spielberg’s direction retains a canvas-like quality. Large chunks of Bridge Of Spies may consist of men sitting and talking in evasive doublespeak, but the movie always articulates itself visually, and its two most suspenseful sequences are both effectively wordless: the opening, in which FBI agents pursue Abel through the streets and subways of late ’50s New York, and the crash of Powers’ U-2 spy plane during a surveillance mission over the Soviet Union. An ode to holding fast to moral principles, geopolitics be damned, becomes a hurrah for old-fashioned big-screen storytelling.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.