Still Here traces Elaine Stritch’s theatrical life from summer stock to 30 Rock

Many of us merely aspire to living a life worth reading about down to the minutest detail, but Elaine Stritch actually succeeded. Best known in 21st-century pop culture as Jack Donaghy’s acerbic mother on 30 Rock, Stritch spent the majority of her life on Broadway, while skirting TV and movie fame.

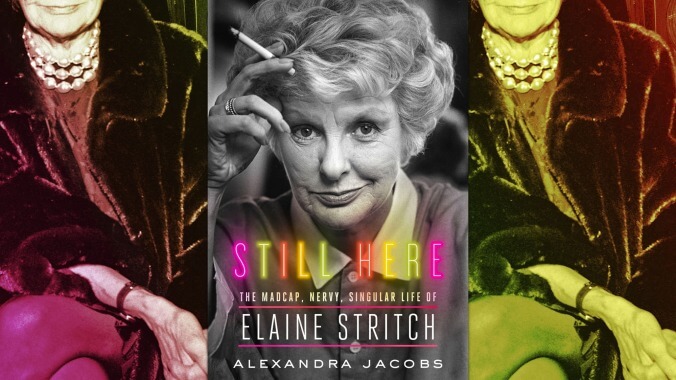

For the new extensive biography Still Here: The Madcap, Nervy, Singular Life Of Elaine Stritch, The New York Times’ Alexandra Jacobs incorporates an astonishing amount of research, including countless personal interviews and physical documents like letters and telegrams. As a result, her portrayal of Stritch is wholly fleshed out, from the actor’s earliest days as a socialite in Detroit to her time as the reigning grand dame of Broadway. That journey takes a variety of twists and turns, but includes such detours as attracting suitors like Gig Young, Ben Gazzara, and Marlon Brando; starring in various Broadway bombs; and moving from hotel to hotel, all leading to her best-known successes after decades in the theater: appearing in the 1970 Stephen Sondheim musical Company and her 2001 Tony Award-winning one-woman show At Liberty.

Still Here will be a boon to those who revel in hearing about short-lived plays and musicals like Time Of The Barracudas and Goldilocks. For everyone else, there are more familiar names along the path to Stritch’s stardom, the actor appearing in plays like Bus Stop and Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Wolff, in parts that took advantage of her acclaimed sardonic wit. She was, for example, a special favorite of Noel Coward’s. One of the book’s many humorous anecdotes involves Coward cautioning her to behave at an important party where Vivien Leigh would be in attendance. After noting that she had “behaved impeccably,” Coward scolded her: “Elaine, I asked you to behave yourself… I did not ask you to behave like a fucking geography teacher.”

Her geography teacher nights were few and far between, however, and Still Here takes an unflinching look at Stritch’s long love/hate relationship with alcohol. Despite an AA stint that she discussed on The Tonight Show, Stritch was for the most part unapologetic about her drinking, bringing the party (usually in the form of a bottle of champagne) with her wherever she went. She even worked as a bartender for awhile at Elaine’s—the famous New York nightspot—between gigs. She once won a part on the TV show The Trials Of O’Brien by walking up to Peter Falk’s table at P.J. Clarke’s and announcing, “Just get me a bottle of vodka and a floor plan.” But Jacobs points out that as Stritch’s reputation as a party girl spread, “She was drinking no more than many of her male contemporaries, but she would pay a far higher price in lost professional opportunities.”

Still Here also makes considerable effort to round out the portrait of the star, with thorns and all: Onstage she was a brilliant performer, but not a particularly generous one, often absorbing all the best lines and moments for herself. She felt like she was in competition with the kind-hearted Angela Lansbury, who got to do parts Stritch longed for like Madame Rose from Gypsy. She blew a chance to be one of The Golden Girls by swearing too much during the audition. The details of her myriad hilarious anecdotes swayed significantly as she retold and retold them.

To capture this multitude of angles, Jacobs made exhaustive efforts to speak with Stritch’s many friends and associates. She tracked down the artist charged with painting the floor of Stritch’s Sag Harbor home while the star was working out her one-woman show with an interviewer, giving her a ringside seat to the creative process.

Stritch also had close relationships with the Broadway gossip columnists who helped make her career, many of whom are quoted in Still Here. Stritch and Dorothy Kilgallen had a lifelong debate over whether it was better for a woman to be beautiful or funny. Stritch once called her up in the middle of the night to announce, “Funny is better.” She knew that a woman’s looks could only take her a certain distance in life; she herself was frequently billed as tall, blond, and striking. But especially in her later years, Stritch’s biting humor became her balm, her defense mechanism, and her signature. Coming home from a trip in which her father died at her mother’s funeral (both were in their nineties), Stritch announced to a friend, “I’ve lost my mother, I’ve lost my father, and I’ve lost my luggage!”

From studying with Brando at the bohemian Dramatic Workshop to Broadway, Stritch was seldom off the stage up until her death in 2014 at the age of 89. Still Here ends with the star saying that under the footlights “was where I lived.” This biography expertly sketches out the vast other hours of her life, painting a thorough picture of a woman who lived life on her own terms—in an age when it was exceedingly difficult to do so.