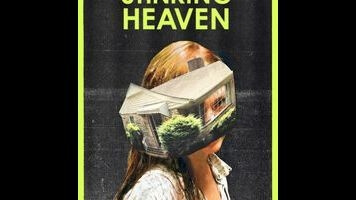

Stinking Heaven’s primitive look is more interesting than its improvised drama

Set in 1990, Nathan Silver’s Stinking Heaven—which is already potentially alienating viewers with that title—looks like a no-budget movie that might actually have been made around then, by someone who couldn’t afford even 16mm film stock. Silver shot it on the Ikegami HL-79E, a camera that was mostly used for TV news broadcasts in the 1980s. Unlike the even more ancient video camera employed in Computer Chess, the Ikegami shoots in color, or at least in a rather sickly approximation of color; it’s the visual equivalent of the home-brewed herbal tea the film’s characters sell on the street, which potential customers practically have to be strong-armed into tasting. Certain lighting produces odd ghosting effects, which Silver embraces rather than avoids. The TV-ready Academy ratio (1.33 to 1) underscores the feeling of watching a curio from decades past, as it might have appeared on VHS or a cable-access channel.

Unfortunately, more thought appears to have been expended on these aesthetic decisions than on the largely improvised drama they capture. (There was no screenplay, apparently—Silver and Jack Dunphy share “story by,” and three of the actors are credited with “additional writing.”) Stinking Heaven takes place almost entirely in a New Jersey house that functions as a self-run commune for recovering addicts. A young couple named Jim (Keith Poulson) and Lucy (Deragh Campbell) are nominally in charge, by virtue of owning the property, but everyone who lives there takes part in regular group activities, including therapeutic re-creations of past traumatic events (recorded on home video for later analysis). It’s a fragile ecosystem, and the sudden arrival of Ann (Hannah Gross, also starring in the current Christmas, Again), who was once romantically involved with Betty (Eleonore Hendricks), who just married the much older Kevin (Henri Douvry), creates a wave of friction that quickly builds into an emotional tsunami.

Or that’s the general idea, anyway. In practice, it doesn’t really work, mostly because Ann, the ostensible catalyst, remains a vaguely malevolent but uninteresting cipher. Her former relationship with Betty, briefly seen in an idyllic skinny-dipping prologue, clearly went sour, and Silver shows Ann behaving like a psycho in a more recent breakup, just before she tracks Betty down and joins the commune (which the others, not very realistically, allow in spite of Betty’s strong protests). But while Gross is very talented, she can’t manufacture a disruptive influence out of thin air, and nothing that emerges from the improvised scenes plausibly creates a toxic environment that will eventually lead to one character’s expulsion and subsequent death.

Like many of Joe Swanberg’s recent efforts, Stinking Heaven plays like a potentially strong idea for a movie that never quite takes shape, which is the problem with “writing” a movie while the camera rolls. Its flaws are nothing that a good second draft couldn’t fix… but that would require making the whole movie again.