In Stonewall, a hunky football player boards a Greyhound in an all-American, cornfields-and-horn-rimmed-glasses picture of the mid-century Midwest, and arrives in a New York of Lou Reed characters, where coverage of the Apollo space program warbles out of every black-and-white TV set and J. Edgar Hoover haunts the suites of a Manhattan luxury hotel in full drag, complete with ruby slippers. Our hunk, plain as his white T-shirt, sleeps on the benches of Christopher Park and in fleabag hotels, dreaming of back home—of the most smoke-machine-pumped high school this side of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and of the family that packed his clothes and secret stash of Drum back issues in a tweed suitcase after he got caught behind a barn with the star quarterback.

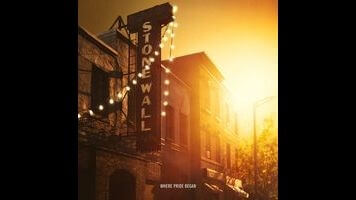

Like Dorothy Gale in The Wizard Of Oz, our hunk finds a new family while traveling down a road—called Christopher Street and lit with enough amber-hued sunlight to look like it’s paved yellow—and together, they arrive at a door answered through a slot. This is the entrance to the Stonewall Inn, where wishes are said to come true, as long as you don’t mind the monthly police raids and don’t drink draft. Inside lurks Ed “The Skull” Murphy, a pimp, extortionist, and former pro wrestler who is almost always framed as a great big bald head. And, yes, Murphy works from behind a curtain, out of an office tucked into the back of the bar; he’s got more than a little Wicked Witch to him, too, the Stonewall being a place with no running water. There’s even a little dog.

Though it delivers disaster-movie specialist Roland Emmerich’s usual mix of pop iconography, cornball Americana, and conspiracy theory, and benefits from some better-than-average performances in hokey roles, Stonewall is a farrago. On the one hand, there’s the Oz-ification of a pivotal episode in the LGBT rights movement, with the aforementioned hunk—named Danny (Jeremy Irvine), but often addressed as “Kansas,” despite being from Indiana—learning to find his way back home with the help of black and Latino street hustlers. On the other, there’s Danny’s last-minute transformation from a completely passive protagonist into the first rioter to throw a brick in the early hours of June 28, 1969, screaming “Gay power!” as though he’d just been stabbed with a high-dosage EpiPen.

Though the decision to insert a mild-mannered, Columbia-bound Midwestern jock into a historical moment that didn’t involve any has drawn Stonewall some pre-release controversy, Danny isn’t the movie’s major problem. Up until the Stonewall Riots, he serves as a stand-in for a closeted queer America, a naïf stumbling through broadly picaresque plotting that finds him seduced by a Mattachine Society pamphleteer (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) and kidnapped by Murphy (Ron Perlman), among countless other incidents, and being introduced to everyone from Marsha P. Johnson to Frank Kameny. The big problem is that Stonewall is fundamentally confused, mixed up to the point where a viewer wouldn’t be able to tell why the Stonewall Riots happened if they didn’t already know.

Accusing Stonewall of conflicting values might be giving it too much credit. Coming off of an underrated, strangely personal Shakespeare truther movie (Anonymous) and a fun Die Hard clone (White House Down), Emmerich seems eluded by the subject matter, despite obvious personal investment. The result appears to be haphazardly quilted from cut pieces; even the centerpiece riot—where Emmerich gets to exercise his yen for destroying iconic locations—is truncated. The movie’s refusal to romanticize life in the period—with the West Village portrayed as a thieves’ den where everything is run by the mob and blackmail and prostitution are the only reliable sources of income—neither squares with its fairy-tale overtones, nor contrasts with them in any effective way.

Hung between all of these half-developed points is Ray (Jonny Beauchamp, quite good), a character whose gender and relationship to Danny doesn’t fall into any strict category, being a (male) potential love interest, a (female) surrogate sister, and a stand-in for Dorothy’s Scarecrow. Perhaps the one good thing about a movie this fragmented is that it ends up producing at least one poignant, complicated character.