Stronger is strongest when letting Jake Gyllenhaal play up the human flaws of a famous survivor

Jeff Bauman can be a fuckup. That, anyway, is how Stronger sometimes opts to portray him: not just as a courageous survivor, not just as a symbol of perseverance, but as an immature knucklehead, too. Bauman was there at the finish line of the Boston Marathon in April of 2013, when two homemade bombs detonated; he awoke a couple days later to discover that he had lost both of his legs in the terrorist attack. Stronger, adapted from his bestselling memoir of the same name, recreates the difficult aftermath of these events, including the uneasy celebrity bestowed upon Bauman, thanks to an iconic photograph of him being rushed to safety by a stranger. And yet far from simply rubber-stamping the prevalent, uplifting narrative of his experience—his public transformation into the living embodiment of Boston Strong—the movie emphasizes flaws, the stuff they don’t engrave on statues or work into human-interest tributes.

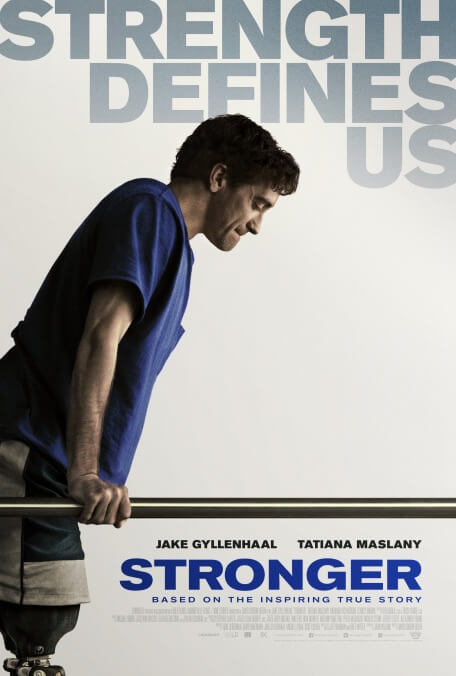

Is it unsparing self-critique we’re seeing here, given the autobiographical source material, or more of a dramatic embellishment, à la The Social Network’s productive vilification of Mark Zuckerberg? Either way, it goes a long way toward making this biopic about a harrowing real-life ordeal a little more complicated than it might have been. Stronger begins, in fact, with a dumb mistake: Working the deli at Costco, Bauman (Jake Gyllenhaal, initially doing his best imitation of an Affleck brother) overcooks the chicken, then somehow sweet-talks his coworker into cleaning up his mess so he can join his friends at a bar for the Sox game. Jeff wants to rekindle things with his on and off girlfriend, Erin (Orphan Black’s Tatiana Maslany), who thinks he’s too unreliable. To prove her wrong and maybe win her back, he’s there on race day to cheer her on; we see the bombs go off from Erin’s perspective, a mile from the finish line.

The film has been directed, but not written, by David Gordon Green (George Washington, Pineapple Express), in what has to be the most workmanlike prestige assignment on an uneven resume of poetic Southern dramas and dopey stoner comedies. Green can’t find a way to work in his signature slow-motion dance (though there is a dark joke about dancing, delivered by someone no longer capable of doing so), but hints of his personality shine through in the scenes of Boston bar-hopping tomfoolery and the more tender moments between Jeff and Erin, reunited through tragic circumstance. Stronger is as much about their relationship as it is about Bauman’s long road to recovery, and Green keeps the focus intimate, mostly resisting the urge to squeeze thrills out of the events of April 15th. (The movie doesn’t inflate, for example, Jeff’s role in identifying one of the bombers; it’s presented as a footnote on his rehabilitation story.)

Gyllenhaal, who’s slowly transformed into one of the most intense actors of his generation, plugs us into this gauntlet of physical and emotional torment. The film takes care to depict the difficulties of adjusting to life with ambulatory disability, but it’s perhaps more concerned with the growing resentment Bauman feels about being asked to relive the worst day of his life on a public stage in order to facilitate a whole city’s healing process. Stronger honors his resistance to being labeled a hero by refusing to unambiguously depict him as one; there’s an integrity to how Gyllenhaal and Green play up his self-pity, his bitterness, even the thoughtlessness that drove him and Erin apart in the first place. To that end, there are flickers of an even more interesting film in Erin’s story—in the implication, real or invented, that she may have fallen back into a relationship with him out of some mixture of guilt and social pressure. (It’s notable, but not noted by the movie, that the two are now in the process of divorcing.) Maslany, who’s equally terrific in a less showy role, exhibits her own slow-simmering resentment toward the expectations put on her.

For as tastefully as Green handles most of this material, there are a few bum notes: However true to life it may be, Miranda Richardson’s performance as Jeff’s needy, alcoholic mother threatens to tilt the movie into shrill Bahstan stereotype, and the eventual, perhaps inevitable flashback to the bombing—which Green withholds for dramatic effect, like the traumatic memory rush of horror in Fire In The Sky—is as borderline exploitative as that famous photo of Bauman being wheeled out of danger. Ultimately, there’s something a little too clean about Stronger’s uplifting upshot, which treats most of Jeff’s doubt and anxiety as a low point in a redemption arc—the obstacle he has to clear in order to realize that being a symbol isn’t so bad after all, if it means helping other people get through their own gauntlets of despair. Maybe the movie will serve the same purpose, lending real value to inspirational trajectory. But Stronger is still strongest when revealing the flawed man behind the rousing story.