Stuck between documentary and drama, American Animals can't make sense of its true crime

The line that once clearly separated documentaries from fictional narratives has eroded so much that certain films are tricky to classify. Errol Morris’ Wormwood, for example, is generally considered to be a doc, even though much of its four-hour running time consists of actors performing scripted scenes. On the flip side, American Animals, which premiered at Sundance earlier this year, tends to get filed under conventional drama, which only makes sense if one ignores or downplays the movie’s recurring talking-head interviews with the real people whose dunderheaded exploits it re-enacts. These are essentially hybrid works, deliberately toying with our ingrained expectations regarding fiction and nonfiction; they’re most interesting precisely at the points where the two uncomfortably overlap. American Animals, alas, doesn’t feature nearly enough of those points to justify such experimentation. It’s a mundane stupid-crime story decked out with empty postmodern frills.

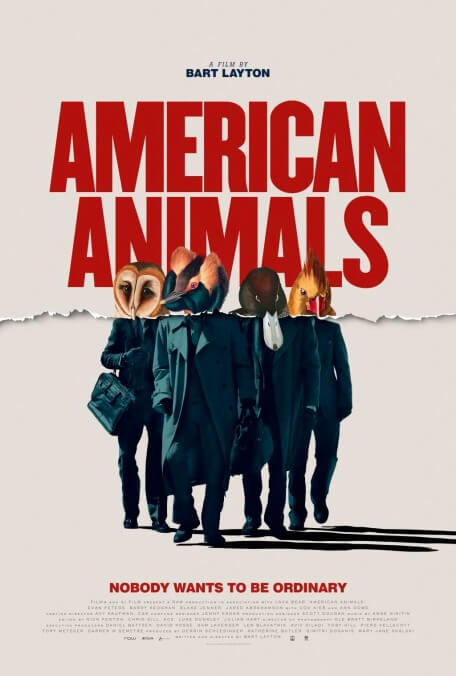

Still, you can see how this particular story caught writer-director Bart Layton’s attention. Back in 2004, a handful of students at Kentucky’s Transylvania University impulsively decided to rob the school library, making off with rare manuscripts (including folios of John James Audubon’s Birds Of America) worth millions of dollars. The four culprits—Warren Lipka (Evan Peters), Spencer Reinhard (Barry Keoghan), Chas Allen (Blake Jenner), and Eric Borsuk (Jared Abrahamson)—disguised themselves as elderly men and physically attacked the Special Collections librarian, Betty Jean “B.J.” Gooch (Ann Dowd), subduing her with a stun gun (or, more accurately, a stun pen). That’s about it in terms of colorful heist detail, and the crime’s aftermath was equally mundane: All four of the young men were apprehended within a few weeks. What baffled the community was their motivation for the robbery, since all of them came from relatively privileged backgrounds and none had experienced any prior trouble with the law.

Rather than explore this question via dramaturgy, Layton just comes right out and poses it to the actual “Transy Heist” quartet, who more or less narrate the entire film as it goes along, explaining their thought processes at every step. That approach worked brilliantly in Layton’s previous film, The Imposter, which allowed sociopathic con artist Frédéric Bourdin to recount the means by which he duped an entire family. But The Imposter isn’t really about Bourdin—it’s about the nature of the human frailty he exploited, which the movie then stealthily, craftily exploits in its own viewers.

There’s no corresponding psychological thesis here. Layton has fun with the representation of conflicting memories—at one point, Reinhard tells Lipka to “pull over” while Keoghan and Peters are sitting on a wall (as Lipka remembers the scene) rather than driving in a car (as Reinhard remembers it)—but there’s nothing meaningful underlying that sort of visual tomfoolery. Nor does American Animals do more than note in passing that these guys used films like Reservoir Dogs and Ocean’s Eleven as models when planning their own caper. Layton sprinkles such meta-elements onto the narrative rather than baking them into it, which makes all the cutting back and forth between real and re-enacted seem indecisive, not incisive. Ultimately, you’re looking at four men struggling to explain an act of post-adolescent stupidity, accompanied by elaborate moving illustrations. It’s moderately entertaining, but the calories feel empty.