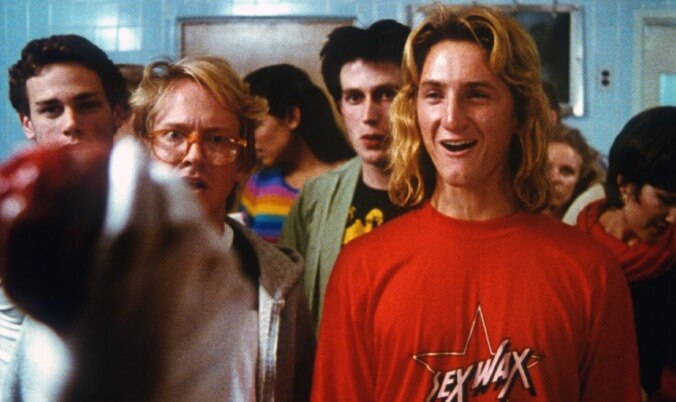

Sean Penn as Jeff Spicoli in Amy Heckerling’s Fast Times At Ridgemont High Photo: Universal Pictures

For cinephiles of a certain age, it is impossible to conceive of a world without a summer movie season. Kicking off on the first weekend of May (or, occasionally, the last weekend of April) and closing out over Labor Day weekend, it’s a four-month smorgasbord of blockbusters, when Hollywood’s dream merchants dazzle us with ambitious visions, state-of-the-art visual effects, and star-studded comedies. There’s at least one glitzy new release every weekend and, if you’re lucky enough to live in a major media center, oodles of critically acclaimed independent films. You’re not going to see many Oscar contenders during this period, but one way or another, you will be entertained.

This was not always the case. Prior to 1975, movies generally opened any old time. Then Jaws shattered just about every box office record, at which point studio executives realized there was serious financial hay to be made when the nation’s children were out of school. This inkling was confirmed, and then some, by Star Wars in 1977. Ditto Animal House in 1978. And Alien in 1979. Suddenly, an industry that spent a decade mashing buttons trying to court the youth market had its cheat code. The era of motion picture maximalism had arrived. Be it sci-fi, fantasy, action, comedy or drama, the answer was to go big. Blow it out. Leave ’em not only wanting more, but lining up for the next screening.

Faith in filmmakers

After a brief period of recalibration, the summer movie season as we know it now began in 1982. That year the studios were throwing haymakers every weekend, offering up mega-budget spectaculars that had to make gobs of money just to break even. For a generation hooked by the escapist yarns of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, this was cinematic nirvana. Going to the movies was like hitting up your local comic book store. People were buying tickets to strange new worlds created by some of the greatest filmmakers on the planet, all of whom were in their prime. Spielberg. John Carpenter. Ridley Scott. John Milius. George Miller. There was a ballsy new comedy from Steve Martin and Carl Reiner that spliced the comic into black-and-white classics from the 1940s. Burt Reynolds and Dolly Parton in a bawdy musical with a naughty title. Tron. What the hell was Tron? You had to find out.

What the studios didn’t understand 40 years ago was that IP is king. For the most part, they were putting their faith in filmmakers coming off massive hits: Spielberg had recovered from the disaster of 1941 with Raiders Of The Lost Ark; Scott was scorching hot after Alien; Carpenter and star Kurt Russell made the most of a shoestring budget with the goofy-gory Escape From New York. Hollywood was, to a significant degree, a director-driven industry. There are no stars in E.T. or Poltergeist. Arnold Schwarzenegger was considered a musclebound charisma void when he made Conan The Barbarian (based on Robert E. Howard’s spottily popular pulp character). Harrison Ford was a delight as Han Solo and Indiana Jones, but a hard sell as the dour Deckard in Blade Runner. Risks were being taken.

Big swings, and some big bombs

Not every risk paid off. In retrospect, this was a watershed summer with a stunningly favorable hit-to-miss ratio, but audiences were content to miss some of the best movies because they couldn’t make sense of the marketing materials. Blade Runner, The Thing and Tron were actually bombs. Critics largely abhorred Carpenter’s remake of Christian Nyby’s 1951 sci-fi classic. Vincent Canby of The New York Times called it a “quintessential moron movie.” Audience word-of-mouth held that it was a ludicrously gruesome downer, which flew in the face of the Reagan Era optimism exemplified by Spielberg’s suburban fantasies. Blade Runner was also too downbeat, even in its truncated state with an over-explanatory voiceover. Tron just looked weird, and, with its video game tie-ins, came on like more of a commercial than a movie.

It’s strange to say now, but the summer’s biggest film, E.T., was also its biggest gamble. Spielberg was not yet the widely revered filmmaking god that he is today. Critics carped that he made popcorn movies; they claimed he valued false, momentary sensation over real, earthbound emotion. For a country that had just crawled out from under its Vietnam War hangover, Spielberg’s unfettered cheeriness felt unearned. Now he was going back to the alien well with another touchy-feely close encounter. Sooner or later, this act was going to wear thin.

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial opened on June 11 to rapturous reviews and thunderstruck audiences. Few films have ever hit the critic/moviegoer bull’s eye so squarely. Even Spielberg’s most cynical critics were forced to concede that he’d made a kindhearted masterpiece (the closest to a contemporaneous pan was the Chicago Reader’s Dave Kerr judging it “fairly irresistible”). The film’s most fulsome praise came courtesy of Time’s Richard Corliss, whose article, “Two from the Heart,” operated as a review of both E.T. and Poltergeist (which Spielberg had meticulously designed before handing it over to Tobe Hooper) as well as a profile of the then 34-year-old wunderkind. It might be the most fawning piece of journalism ever penned in the English language: “Not since the glory days of Walt Disney Productions … has a film so acutely evoked the twin senses of everyday wonder and otherworldly awe.”

Spielberg, who was already the King of Summer thanks to Jaws and Raiders Of The Lost Ark, unabashedly concurred with Corliss’ assessment, saying “I put myself on the line with this film, and it wasn’t easy. But I’m proud of it. It’s been a long time since any movie gave me an ‘up’ cry.” This brazen self-confidence likely played a role in Oscar voters opting for the vastly inferior Ghandi at the 1983 Academy Awards, but what did that matter? By the end of E.T.’s first theatrical run (which stretched into late 1983), it was the top grossing film of all time. Oscars or no, Spielberg was now the King of Hollywood.

The cineplex arrives

The anointing of Spielberg was significant, but the summer’s most pivotal development in terms of the film business was the continued proliferation of multiplex theaters. Chains like National Amusements and AMC were erecting massive complexes all over the country, which allowed studios to frontload openings on 1,000-plus screens rather than roll their hits out more slowly over several months. Paramount Pictures, sweating a Trekker mutiny due to the widely reported death of Spock, took full advantage of this newfangled opportunity by launching Star Trek II: The Wrath Of Khan on 1,621 screens over the weekend of June 4. They were rewarded with a record-breaking $14 million three-day gross, more than twice the opening take of Poltergeist. Other studios didn’t immediately change their release strategies (e.g. 1983’s uber-anticipated The Return Of The Jedi debuted on a modest 1,002 screens), but by the early ’90s, it was customary for tentpole titles to go as wide as possible in their opening frame. There was simply too much riding on their massive budgets to dick around with a word-of-mouth-based platform release.

It took studios a while to figure out how to program August. In ’82, the last full month of summer was a bit of a dumping ground, home to oddball programmers, slasher flicks and teen sex comedies. The biggest surprise of this bunch was Amy Heckerling’s Fast Times At Ridgemont High, which opened to mostly dismissive reviews (and one infamously hostile notice from Roger Ebert). Universal Pictures had zero faith in the film’s sleeper potential, which is reflected in its unspectacular $27 million domestic gross, a far cry from Porky’s still-shocking $102 million first-run tally. Paramount made a quick killing with the gimmicky 3D of Friday The 13th Part III, while riding high off July’s surprise crowd-pleaser An Officer And A Gentleman. 20th Century Fox jumped into the void with its fourth re-release of the not-yet-available-on-VHS Star Wars. Films like Fast Times and The Last American Virgin (released to scathing notices on July 30) would find their followings on home video and pay cable, the first disquieting signal to exhibitors that moviegoers could happily wait to see certain titles.

Banking on spectacle

This is the Summer of 1982’s true legacy. In prioritizing big-ticket blockbusters and splashy sequels from the era’s top commercial filmmakers and movie stars, studios began to undercut the need-to-see appeal of their bread-and-butter dramas and comedies. Coupled with rising ticket prices, this shift in release strategy gradually gave audiences pause. Why rush out to see Ron Howard’s visually ho-hum Night Shift when it’ll be available to rent from the local video store within the next six months? Going to the movies would continue to be a great American pastime for decades to come, but what people deemed theater-worthy changed with each passing year. Forty years later, the nation’s cinemas have ultimately become amusement parks, delivery systems for cutting-edge CG showcases and the occasional cheap horror-movie thrill.

Want proof? Just ask Steven Spielberg. In 2021, his wildly celebrated, $100 million remake of West Side Story bombed at the box office with a $38 million domestic take, while the latest Spider-Man movie became the third-highest grossing movie in film history. There were complicating factors (namely December’s Omicron surge scaring off older moviegoers who would’ve been a key target for West Side Story), but the hard truth is that young viewers simply didn’t care to buy a ticket for a film based on a 64-year-old production absent superheroes, dinosaurs or dazzling action set pieces. Aside from rare exceptions like Jackass Forever, they don’t buy tickets to straight-up comedies anymore either. Those go straight to streaming. Ditto dramas. It’s all sensation, all the time on the big screen now. Thanks to, or because of, the lessons from 1982, much of the film industry now exists in an endless summer haze, a year-round business that’s always awaiting that next blockbuster jolt at the multiplex.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)