Supernatural thriller The Perishing is a luminous love letter to Los Angeles

In consistently gorgeous prose, Natashia Deón rivals Nelson Algren’s Chicago: City On The Make when she writes about L.A.

Five years ago, Natashia Deón’s debut novel was named one of the best books of the year by The New York Times. Narrated by the ghost of a murdered slave, Grace slipped effortlessly between the past and the present, life and the afterlife. “Ms. Deón is not merely another new author to watch,” wrote Jennifer Senior in a rave review. “She has delivered something whole, and to be reckoned with, right now.”

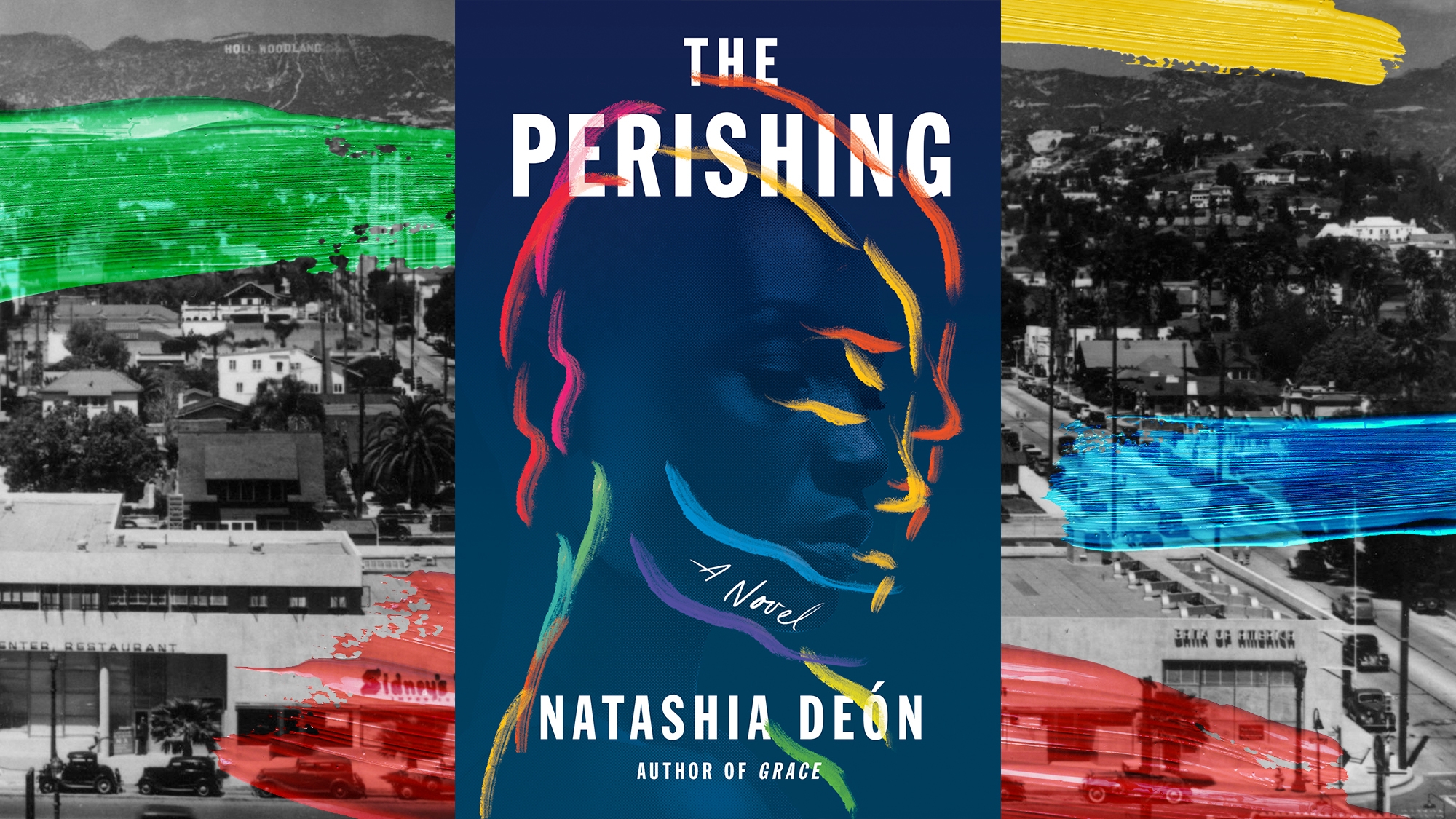

After a debut like that, what’s a writer to do next? Judging by the packaging of her second novel, The Perishing, Deón decided to do something completely different. The description on the back cover positions The Perishing as a supernatural historical thriller in the vein of Matt Ruff’s Lovecraft Country or P. Djèlí Clark’s Ring Shout. It’s not hard to understand why the publisher is marketing the book this way; it’s the same reason that trailers for M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village promised a creature feature like his previous film, Signs: Some stories don’t fit neatly inside a genre box, but bookselling and moviemaking leave little room for nuance when it comes to advertising.

If you’ve seen The Village, you know it’s more Gothic romance than monster horror. And if you read The Perishing, you’ll see it has more in common with Deón’s debut—or Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing or Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, books in which the speculative conceit plays third fiddle to characters and settings grounded in reality—than the book jacket indicates. If you approach it without genre-specific expectations, The Perishing is a startling, luminous love letter to Los Angeles and one of the best books of 2021.

The Perishing opens with a 30-page prologue that bounces between the year 2102 and the late 19th century, as an immortal narrator remembers snippets of past lives. “Life after life in new bodies, new cities, and new countries where I’ve always been Black, not always a woman,” she says. We meet her as Sarah Shipley, a California woman on trial for murder a century from now; as Charlie, an Arizona boy whose grandfather goes missing in 1887; and as a nameless girl living by the Dead Sea sometime in the distant past. These brief opening chapters are disorienting, as Deón establishes the temporal confusion an immortal mind might experience.

But then: “1930 was the decade I learned to fight back,” Sarah says near the end of the prologue, and we meet her once more as Lou, a young Black woman who wakes up naked and memoryless in a Los Angeles alley, and who grounds the rest of the novel in a hyper-specific time and place. At this point in her immortal journey, Lou doesn’t remember any of her past lives, much less where her current body came from. Over the next 200 pages, as meta-narrative clues slowly accumulate, Lou blossoms into a fiercely intelligent journalist, first at her desegregated high school, then as the first Black female reporter at the Los Angeles Times. She starts on the “death desk” (perfect for an immortal, right?) before covering real-life history as it happens, like Route 66’s displacement of Black neighborhoods.

In consistently gorgeous prose, Deón rivals Nelson Algren’s Chicago: City On The Make when she writes about L.A. “Los Angeles has always been brown. And unlike all the other great American cities—New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston—there is no sensible reason for Los Angeles to exist,” Lou says in an early chapter.

Los Angeles was born with no natural port, no good river connections, no suitable harbor sites, and no critical location advantage. And precisely for these reasons—because being born with very little and having no safe place are the fuels for the greatest imaginations—Los Angeles would rise. Imagination and enthusiasm are the currency of world builders.

Perhaps it’s no mistake that in Deón’s telling, Los Angeles is as much a temporal anomaly as Lou is.

As she grows into her life, Lou discovers her wounds heal instantly. Her dreams take her to times and places she’s never seen, like an English cathedral in the year 1620. And over and over again, she draws the face of a man she’s never met—until the day she does. All the while, Sarah Shipley crashes into the novel from the 22nd century every few chapters for a brief section of her own.

In its final 50 pages, The Perishing’s immortal frame narrative takes center stage again and sprints to a surprising conclusion. If you’ve enjoyed Lou’s chapters purely as historical fiction, the denouement may strike a dissonant chord. But it’s as brilliant and unprecedented as the rest of the book, sheds new light on the opening chapters, and sews all of Deón’s narrative threads back together in a uniquely satisfying way. Grace may have announced the arrival of a singular new voice, but The Perishing does not sit in its shadow; it burns as bright as the Hollywoodland sign once did, “studded with four thousand light bulbs.”

Author photo: Brienne Michelle