Survivor’s “#MeToo moment” protected the game instead of the players

At the end of Survivor’s 38th season, castaway Julia Carter wrote a lengthy blog post detailing her experience playing the game, particularly as a person of color. Among those experiences were multiple instances of racial slurs being used by her fellow castaways, a circumstance that was only addressed by her tribe when a white castaway objected on her behalf. The result was a healthy dialogue at camp, and a confessional where Carter—one of only two Black castaways on the season that aired in the winter and spring of 2019—remembers reflecting on “how saddening it is to have to deal with such overt racial differences during my once-in-a-lifetime Survivor experience.”

None of it made it on TV.

When I read Carter’s blog post, it didn’t shock me: It wasn’t unexpected that the white majority on a reality show would be insensitive to issues of racial difference, and it wasn’t surprising that Survivor’s producers would consciously avoid engaging with these issues in the final edit of the season. While the CBS series has always presented itself as a microcosm of society, the show’s casting patterns have consistently positioned non-white castaways as tokens within majority white casts. The “social experiment” largely perpetuates the marginalization of people of color and women within the America it seeks to represent, with those individuals often being identified as targets and eliminated early on.

However, this isn’t part of the experiment that CBS wants to talk about. Whether due to aftershocks from the public backlash to the season with tribes divided by race, or simply due to the perceived conservatism of the show’s audience, Survivor has rarely positioned these kinds of social issues as a significant part of its narrative.

Until now. Over the past three weeks, Survivor’s 39th season has leaned into its place in contemporary discourses surrounding race and gender, a conscious campaign to convince us of its capacity to reckon with racial insensitivity and sexual harassment. But given how these efforts played out in this week’s two-parter, “We Made It To The Merge!”, the series’ current approach is incapable of reckoning with moments where meaningful dialogues intersect with a game of individual survival where outplaying your fellow castaways outweighs all over priorities. The result is a disastrous reach for a “#MeToo moment” that proves Survivor’s ability to reflect social realities, but in all the wrong ways, and with a truly toxic moral for those watching at home.

These issues first emerged two weeks ago, in an off-hand comment where well-meaning Jack (a white castaway) referred to his Black tribemate Jamal’s Buff—the multipurpose piece of wardrobe that signifies a castaway’s tribal allegiance—as a “do-rag,” creating tension between the two allies. This prompted Jamal to guide a regretful Jack through a dialogue about racially charged language and white privilege. Then last week, as the men at tribal council (including Jamal) raised the specter of a “women’s alliance,” Kellee objected on behalf of her fellow female castaways, outlining the institutionalized sexism underpinning this fear—no one ever talks about a “men’s alliance” in the same way, after all. In both cases, unlike Carter’s experience, the moments weren’t hidden within the edit: Jamal was given considerable confessional time to articulate his reasons for needing to address the issue, while host and producer Jeff Probst leaned into Kellee’s comments during tribal council, gesturing to the #MeToo movement to elevate the discourse.

However, both moments reinforced how there are certain types of confrontations that can be safely addressed within the confines of Survivor’s worldview. While similar in theme to Carter’s unaired situation last season, the racial insensitivity dialogue has key differences: Jack didn’t use an explicit racial slur, he was immediately regretful without being told he had to be, and Jamal’s role of the patient Black man educating his white ally fits into palatable tropes of racial healing (See also: the odious yet Oscar-winning Green Book) in a way that an “emotional” (itself a loaded word) Black woman explaining her feelings doesn’t. And in both cases, producers brought these dialogues to the surface but were able to comfortably push them back into the background when it came time to “play the game”: the episodes may have leaned into issues of race and gender, but the endings were still about blindsides, hidden immunity idols, and the familiar rhythms of the series’ storytelling.

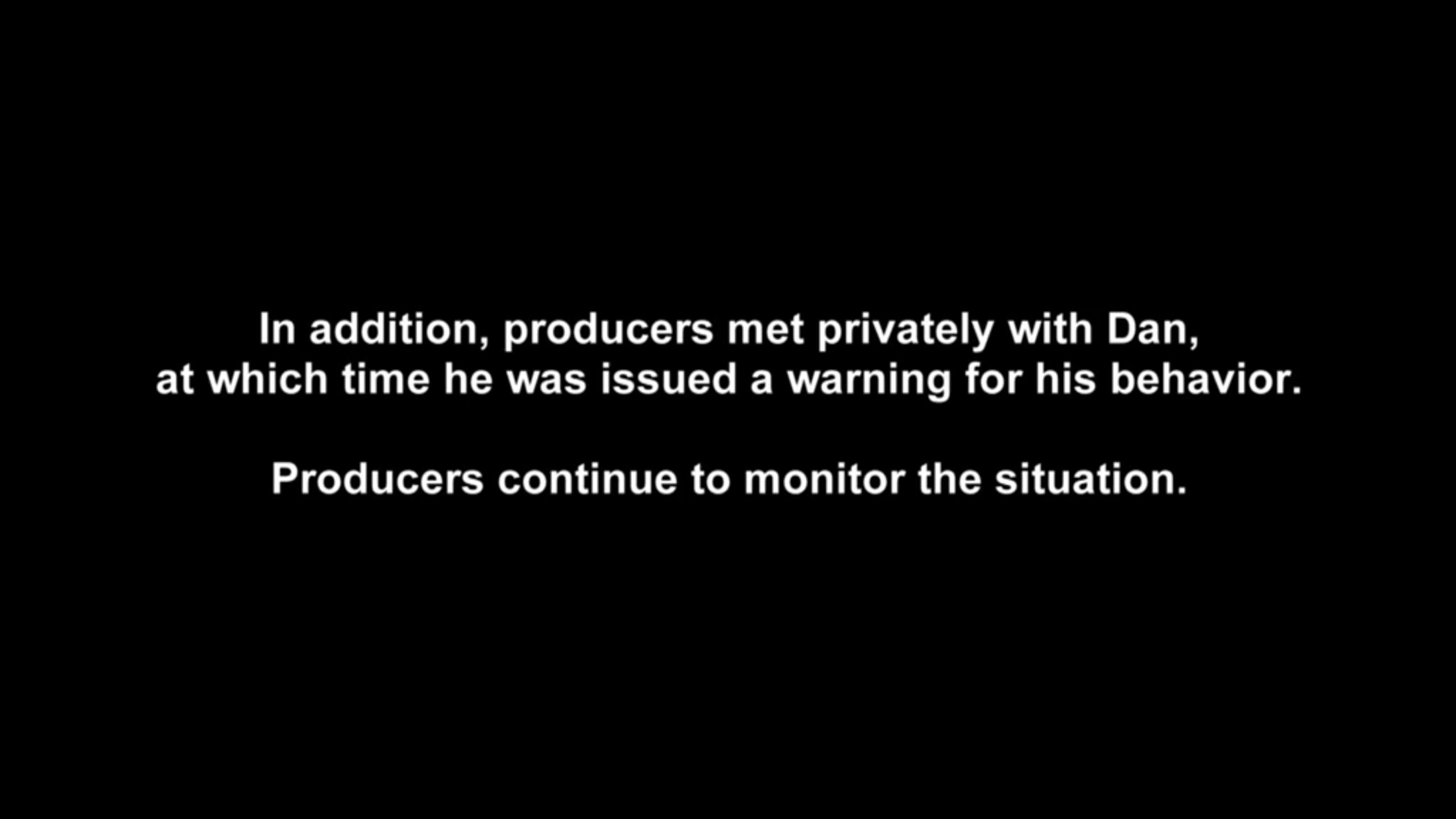

To Survivor’s credit, though, the show seemed to understand that “We Made It To The Merge!” was different. It opens with a content warning for mature themes, and as soon as the tribes merged, the show commits to telling the story of talent manager Dan’s misconduct, in the form of inappropriate physical contact with the women in the game. This isn’t the first time we’ve seen some of the footage played while Kellee and Missy discuss the issue: Since Survivor has the benefit of hindsight when crafting a season’s narrative, earlier episodes dealt briefly with the discomfort women felt with Dan while sleeping in the shelter, or in their general interactions with him. But as the two women reveal additional instances, more footage is added, and as Kellee discusses the issue in a confessional, the editors deliver a reality show’s ultimate signal that something is not right: We hear the offscreen producer ask Kellee if things have gotten bad enough that she wants them to intervene. And while she insists that she believes the presence of the maternal Janet will be able to keep Dan in line, the show goes to commercial with a series of chyrons detailing that producers spoke to the entire tribe about boundaries, and issued a formal warning to Dan specifically.

It’s an incredibly rare acknowledgment of producer intervention, on multiple fronts, but the approach mistakes transparency for accountability. Why was Dan not warned by production when his inappropriate touching began, and production documented Kellee inventing a germophobia to escape it? Did none of the camera operators who observed his wandering hands in the shelter alert production to what they were seeing? Why was it the responsibility of the players to bring this issue to the attention of producers when there are cameras around recording everything that’s happening? While Dan’s actions were not as unanimously understood as disqualifying as those which led to the no-vote removals of Jeff Varner and Brandon Hantz from the game, how is it that past issues of documented sexual misconduct within Survivor have not created clearer policies for identifying and preventing this kind of behavior? Survivor acknowledged how it addressed this issue in real time, but the producers failed to address how their production process allowed it to get to a point where Kellee, in light of being sexually harassed, makes the decision that she needs to adjust her strategy in the game to remove Dan.

Unfortunately for Kellee, however, Survivor works just like the real world when it comes to such allegations. While Kellee initially received support from other young women in her tribe, they ultimately side with her harasser, with the majority choosing to vote out Kellee instead. Janet votes in solidarity with Kellee, and when she returns to tribal council she is confronted by a truly galling set of behaviors by everyone involved. Lauren, who initially showed support for Kellee, tells Janet that she didn’t feel comfortable voting someone out because of someone else’s experience, since she doesn’t want to take a side in a “he said/she said” situation. When Janet confronts Dan directly about his behavior—pointing out that the speech to the tribe was, you know, about him—he rejects the accusation out of hand, and tries to reframe Kellee’s elimination as punishment for inventing (or, if we’re generous to Dan, exaggerating) the allegations in order to make a strategic move in the game. And when Janet goes to Missy and Elizabeth—who had exaggerated the allegations by strategically adding Elizabeth’s testimony despite her lack of discomfort—and ask them to confirm what they said to her, Elizabeth admits to expressing those feelings but then immediately tells Dan that she was just lying to get Janet off her back. As Kellee sits eliminated from the game, Janet finds herself stranded on an island with people trying to erase Kellee’s experience and dismiss her concerns as opportunistic—in other words, she was reminded that the players on Survivor recreate the world they left behind, where Kellee would have been treated similarly.

Except that Survivor actually creates an even worse environment than the real world when it comes to allegations of this nature. Survivor takes the neoliberal mantras of personal responsibility that pervade society and presents them as the very nature of our existence. Like many competition reality programs, it balances elements of cooperation with an ethos of individualism, encouraging collaboration but ultimately teaching players that the only way to truly survive (read: win) is to look out for yourself. It’s this very ideology that encourages people to ignore when women (or men) speak out about sexual harassment, because that would mean sticking your neck out for someone else, and taking a moral stand in an environment where such morality is perceived as either a threat, a weakness, or both. And while this exists in workplaces and social groups and even families, Survivor reduces every waking hour of its 39 days to this type of thinking. And thus, by the ethos developed and internalized by the show, its players, and its viewers over the past 19 years, Kellee and Janet were the ones who transgressed the norms of the game, not Dan (or Missy and Elizabeth)—and even if the producers don’t actually believe this is true, the “game” disagrees, because the only people held accountable here are Kellee and her ally Jamal, who goes home in the episode’s second tribal council.

That tribal council is among the most infuriating 15 minutes of television Survivor has generated. As Janet tries to explain the moral underpinnings of her decision, she is stopped by Aaron, a male castaway who insists that her actions were simply a Survivor gameplay decision that failed. He talks over Janet, claims she is trying to play the role of victim (as opposed to defending a victim), and makes the argument that while he is totally supportive of these kinds of accusations in the “real world,” it’s not supposed to be part of Survivor. Dan chimes in to agree, baffled that Janet’s use of the accusations as gameplay hasn’t just been acknowledged as a mistake and dismissed entirely, and offended that host and producer Jeff Probst would keep bringing it up. And while Jamal steps in to once again patiently explain how to be an ally to those who are marginalized from power, Dan still “explains” himself with an exasperating speech about how his family and his job in Hollywood where #MeToo originated mean he would never knowingly do what we’ve literally seen him do, and ends it with another insistence that the real issue is that someone would turn such an accusation into “gameplay.” And this whole time, Kellee is forced—by tradition, as a member of the jury—to sit silently, unable to defend herself or her experiences.

Probst tries to present a summary of what happened, arguing that such scenarios are “why [Survivor] is so complicated to play, but so compelling to be a part of,” but how is it compelling to have your experiences questioned by the men and women in power, and to have your allies systematically targeted after speaking up on your behalf? After Jamal is voted out, Probst offers another pithy summary, noting “once again, a lot of raw emotion, different opinions, big ideas, and at the end another person voted out.”

But that is the essence of why Survivor cannot truly deal with these issues within the structure of its game: There were plenty of big ideas, but in the end the majority voted to remove those “disrupting” the game and silenced them in the process. And while Missy, Elizabeth, Lauren, and Aaron have publicly apologized for their actions, a small percentage of the show’s audience will see those apologies—compared to the millions who saw Dan’s actions validated by the castaways’ votes.

In multiple interviews with Probst released after the episode aired, he is almost self-congratulatory, proud of the fact that the show is addressing these important issues, but he fails to acknowledge that the show’s lack of action against Dan resulted in a moral of “If you speak out against someone who is sexually harassing you, your concerns will be dismissed.” By allowing the rules of the show to arbitrate this extremely serious situation, and by allowing Dan to present himself as the victim and then be validated by the results of the votes, Probst and the producers have not simply waded into a discourse: They have presented a horrifying parable over which they have no control. The editing choices leave room for someone who believes women routinely falsify or exaggerate allegations to ruin men’s lives, allowing these wrongheaded viewers to think that it was Kellee and Janet—and not Missy and Elizabeth—who used this as “gameplay.” And while Jamal may have pushed back on Aaron’s argument this conversation has no place in the game of Survivor, viewers will see the conversation fade away as the show returns to “normal,” until the finale and reunion gives Kellee and others their voice back.

Survivor wants credit for not having swept this under the rug, despite the fact that the show created the conditions that allowed it to happen and chose to let the issue be resolved in a deeply toxic way. Survivor wants us to applaud Jeff Probst for bringing up #MeToo, despite the fact he does so without acknowledging how his own valorization of masculinity and ridicule of female castaways (especially in challenges in seasons with gendered tribes) are part of the problem. Survivor wants us to believe that the fact the castaways are litigating issues of race and gender means that the show can simply present both sides and absolve itself of responsibility, when the reality of the game means that many people watching will accept Kellee’s decision as a “gameplay mistake,” with the accompanying conclusion that Janet and Jamal’s choice to support her was an even bigger error because they endangered their game to help someone other than themselves. And somehow, Survivor want us to keep watching a season in which pretty much every remaining castaway but Janet has shown themselves to be actively or passively allowing this entire debacle to unfold.

In her blog post, Julia Carter wrote that after her unaired incident “it hurt me to feel as though I was back in that place in my life where I felt so silenced, that I would choose $1 million dollars over defending myself. In that moment, I chose the game. I stand by that decision, but never again.” In his interview with Entertainment Weekly, Probst claims that Survivor is about this ethical dilemma:

“Where does each player draw their line in the sand? What is okay to do or say and what is off limits? And the bigger question: Are there certain situations that are simply off limits, no matter what?”

And while the balance of morality has always been at the heart of Survivor, the idea that this extends to racial slurs and unwanted physical contact is ludicrous, and a fundamental breach of the responsibility the show has to its castaways. If Survivor is a game where players are conditioned to see reporting sexual harassment or standing up to racist language as “bad gameplay,” then it is a broken game. And until the producers acknowledge that this situation was preventable and handled in a way that irrevocably shattered their trust with their players and their viewers, it’s difficult to imagine tuning in to watch them try to pick up the pieces.