Ta-Nehisi Coates reimagines the plight of American slaves in the mythical Water Dancer

Ta-Nehisi Coates is a Civil War buff. The lauded journalist and cultural critic has read book after book on the subject, dragged his family to visit battlefields during summer vacations, and can even pick out the flaws in Ken Burns’ nine-part series. For a Black man, it can make for a lonely endeavor, especially when traveling through battle sites where the war is often framed as a national tragedy instead of a reckoning. “[F]or my community, the message has long been clear: The Civil War is a story for white people—acted out by white people, on white people’s terms,” he wrote in his 2011 article “Why Do So Few Blacks Study The Civil War?” “[T]o speak as the slave would,” he continues, “to say that we are as happy for the Civil War as most Americans are for the Revolutionary War, is to rupture the narrative.”

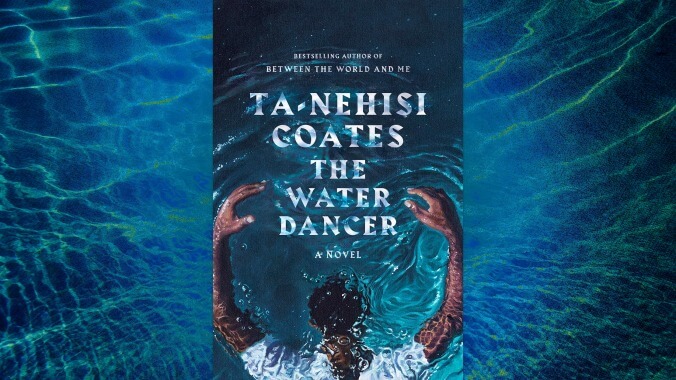

Well, here comes his fiction debut, The Water Dancer, to do some rupturing.

The novel’s protagonist, Hiram Walker, is a slave with a photographic memory who cannot recall his mother, who was sold away. As the son of the master of Lockless plantation, he is spared from the fields and assigned as the main attendant of his half-brother, Maynard. Years later, a river accident takes Maynard’s life and almost causes Hiram’s own death, until a vision of his mother unleashes a secret gift—Conduction—that transports him out of harm’s way. The event pushes him to escape to the North, in a journey that entangles him in an underground movement against slaveholders and sets off a soul-wrenching mission to unearth a past he’d rather forget. Coates has argued that for African Americans, the Civil War started way before 1861, and this novel is a magical reimagining of that centuries-long fight for freedom.

The Water Dancer fits in nicely with Coates’ grander project of writing as a corrective exercise to the whitewashing of the nation’s historical memory, as in his bestselling Between The World And Me and his work for The Atlantic. Its greatest strength is how it functions as a counter-myth to the supposed romanticism of the Antebellum South that has so propagated mainstream culture. (Gone With the Wind, anyone?) His world-building of the decadent Virginia plantations is impeccable and comes with its own unique vocabulary, as a way to shake us out of our own complacent understanding of the time period. Here, “Conduction” is a gift, “Tasked” are the enslaved, and “Quality” are slave owners, though there is an undercurrent of irony to this last one. The ladies and gentlemen of these estates are not some genteel American version of Downton Abbey’s the Crawleys; instead, their monstrosity and vulgarity are apparent. Take this description of a woman who “stopped cackling and pulled down her bonnet, revealing a broken mask of streaked face-paint” before slapping a man-in-waiting, demanding songs. There’s no nostalgia here, no old glory to mourn—only nightmares.

And no one is more vulgar than Maynard, a Trump-like figure who is a brutal takedown of the Mediocre White Man as we understand him today (though even Maynard has more redeemable qualities than 45). One of the deliciously satisfying elements of the novel is the parallel it creates between the past and the present. Which is fitting, considering that one of Coates’ longstanding concerns is to demonstrate how our slave past keeps shaping our current life. We get echoes of our contemporary landscape in the problematic white feminist ally and the band of low whites who do the dirty work for the Quality, but the analogies aren’t restricted to characters. There are hints of the collapse of traditional industries, the ecological disasters of hyper-capitalism, and a particularly vivid scene in an abolitionist conference that speaks to all the unfulfilled promises of America.

The Water Dancer’s emotional core, though, is the generational violence inflicted upon families. Hi’s determination to rescue Thena, the woman who took him in as a young boy, and Sophia, his love interest, thrusts the action forward and serves as an examination of how tearing apart families has warped our nation-building. This isn’t a sentimental point. Family separation has long been the crime of choice in an America committed to white supremacy. The Water Dancer is insistent on how each severed tie represents a mortal blow to the principles the country is supposed to hold dear.

After a compelling beginning, the book flounders for several chapters before picking up steam again. The hero’s journey that may work well in Coates’ Black Panther graphic novels ends up feeling like a string of unnecessary delays here. As Hi tries to tap, control, and harness the power of Conduction, there are adventures, losses, triumphs, and setbacks for him and the ragtag team of abolitionists and freed men he meets. It’s the most cinematic aspect of the book, and therein lies its weakness. It treads along like a long, self-indulgent battle sequence in one of the numerous Avengers movies out there. The dialogue can come off as stilted and expository, and the prose is interrupted with theoretical analyses that are intoxicating to read in essays but come off as pontification in fiction. One wishes Coates’ incisive commentary and conceptual clarity would take a step back to allow his characters to be messy, inconsistent, and a tad less self-aware. In short, a bit more human than mythical.

Still, there is more to like than not in a novel that makes a strong case for confronting our individual and collective pasts as a way forward. As one of the characters says, “memory is the chariot, and memory is the way, and memory is bridge from the curse of slavery to freedom.” It asks us to push against a dominant national memory and urges us to conjure up other recollections, those hidden and erased from the annals of history.