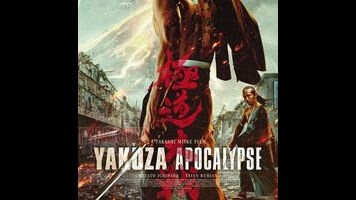

Takashi Miike returns to midnight movies with the crazed Yakuza Apocalypse

When Takashi Miike first caught the attention of American genre fans in the early 2000s, it was as a purveyor of the sick, the twisted, the out-there, and the then-trendy extreme. At the time, the Japanese director was a one-man cottage industry, cranking out a half dozen or more features a year, and if he ever had a signature genre, it was the gangster movie—the yakuza’s blend of middle-management and violence being fertile ground for someone with a mind for the bizarre. It was the horror flicks, though, that made Miike’s name in the West. Perhaps it’s because horror is a genre in which the unexpected is a requisite, as paradoxical as that may sound.

Nowadays, Miike’s slowed down to about two movies a year; his budgets have gotten bigger, and his style has gotten a bit more elegant. His latest, the deranged and frequently funny Yakuza Apocalypse, is in many ways a return to both his early years in the wilds of V-Cinema—Japan’s direct-to-video industry—and to the kind of midnight-movie fodder that first made his reputation abroad, albeit done on a much larger scale and with fewer quirks of style. It begins like a Kinji Fukasaku movie on speed—which is to say, a little like Miike’s Deadly Outlaw: Rekka—with local boss Kamuira (character actor Lily Franky) slicing through a dozen or so members of a rival gang. Cue the Goodfellas narration and the introduction of Kageyama (Hayato Ichihara), a young man who, in a typically goofy touch, has always wanted to be a yakuza, but can’t, because he’s allergic to tattoo ink.

And then come the yakuza vampires—that is, vampires whose victims rise from the dead as low-level yakuza, sprouting punch perms, bad attitudes, and a general air of macho laziness. The thing about yakuza vampires is that they can only feed on the blood of the innocent; Kamuira is one, and he keeps his former rivals prisoner in a dungeon underneath a restaurant, where they learn manners and knit so that he can periodically feed on their now crime-free blood. Inevitably, things get out of hand, and the whole town gets overtaken by the newly risen undead, who sit around barefoot playing dominoes and try to muscle each other for shakedown money; the situation gets so bad that the last living gangsters are forced to grow their own civilians in a greenhouse.

On its own, the premise amounts to a kooky satire of the parasitic culture of organized crime—an extended skit about what mobsters would do if everyone else became a mobster. Miike, the king of the gear-switch and the out-of-nowhere ending, has never really been one to play things straightforward; when he does, it’s only to set up a bait-and-switch. (See: Audition.) There’s nothing quite as sophisticated going on here. Instead, Yakuza Apocaypse just adds more and more supernatural elements into the mix: the addition of vampire assassins, one of them a foreign nerd (The Raid’s Yayan Ruhian) with ’80s yearbook-photo glasses and a backpack full of anime posters; the barely acknowledged introduction of a kappa—the beaked, foul-smelling turtle-goblins of Japanese folklore—as a supporting character; the introduction of a fearsome, mysterious martial artist in a ratty frog mascot costume.

Scene by scene, the movie builds toward the big conflagration hinted in at the title, until the characters begin sprouting wings and a kaiju monster appears on the horizon. A diehard fan can’t help but miss the poignancy that Miike was able to invest into his scattershot early films, where his creativity often outmatched his resources. Still, Yakuza Apocalypse is the kind of free-for-all only Miike could stage—pitting not merely different characters, but different genres and tones against each other, until the world cracks in two under the weight.