Let me confess that I empathize, at least to a degree. Unlike Tarantino, I don’t despise or even dislike Ford, who made plenty of films that are indisputably great. But I do find that his treatment of Native Americans gets in the way of my enjoyment, at times to a significant degree. (In Ford’s early pictures, they’re not even Indians—they’re Injuns.) Obviously, watching old movies requires a certain amount of flinching at the more overt racism of the past, and Ford is by no means the only offender; if you want to watch Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney perform an entire musical number in blackface, you can do that right now. But Ford’s scenes featuring Indians frequently aren’t just offensive by contemporary standards—they’re also tonally divorced from the rest of the movie in a destructive way. That’s even true of The Searchers, a masterpiece that I like and admire but have never quite been able to bring myself to love. Since I happen to have just watched 1939’s Drums Along The Mohawk, however, let me share the scene that abruptly yanked me out of that film, and see if I can articulate why it bothers me.

First, some quick context. Drums Along The Mohawk isn’t a comedy, though it does have some other lighthearted moments. (Many of those involve this elderly widow, Mrs. McKlennar, played with delectable bluntness by Edna May Oliver. Oliver was nominated for the Best Supporting Actress Oscar, but lost to Gone With The Wind’s Hattie McDaniel.) Set during the Revolutionary War, the film follows the struggle of a married couple, Gil and Lana Martin (Henry Fonda and Claudette Colbert), to make a home for themselves in New York’s Mohawk Valley as fighting breaks out all around them. Earlier in the film, the Martins’ house gets burned down, along with all their crops, by marauding Indians who have joined forces with the Tories—not the modern-day political party, but colonists who remained loyal to the British Crown. Later in the film, Indians will try to burn a colonist alive, in what’s essentially an act of terrorism. (They want an audience.) Ford takes these acts of war seriously, and makes it abundantly clear that a Tory named Caldwell (John Carradine) is behind them. He also delivers a truly powerful scene in which a badly wounded Gil recounts the horrors of the battlefield.

That’s what makes this scene so weirdly jarring. When the Martins’ house (along with many others) gets burned down earlier in the movie, it’s seen mostly at a distance as the colonists flee; the Indians are certainly “faceless” (to use Tarantino’s objection), but only in the way that, say, the stormtroopers in the Star Wars series are faceless. Ford treats the sequence with the gravity it deserves—people are terrified and distraught. If there’s an objection to be found, it’s that Colbert overdoes Lana’s shrieking. (Lana also shrieks up a storm when she first encounters Drums Along The Mohawk’s designated friendly Indian, Blue Back, who’s treated by Gil as a great, trusted friend. She has to be slapped out of her hysteria, but ’30s sexism is a whole other essay of its own.)

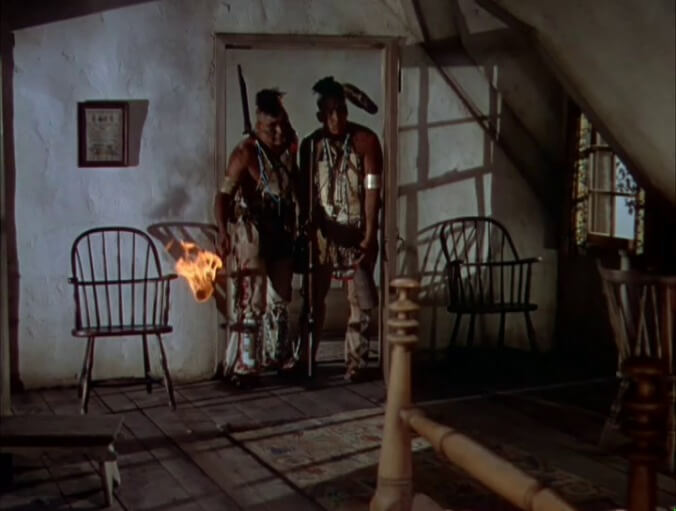

At Mrs. McKlennar’s, by contrast, Ford has inexplicably chosen to depict Indians sneaking into a house with the intention of burning it to the ground as if they were frat brothers TP-ing the dean of students’ front yard. As is often the case in Ford’s movies, one of the Indians constantly takes swigs from a jug of liquor, which enhances the air of tomfoolery. As opposed to murder.

To be fair, these two Indians apparently don’t actually want to kill Mrs. McKlennar, as they keep saying things like “You go quick, old woman! You catch fire!” Property damage is the objective. All the same, the tone of this scene is so goofy and cartoonish that it makes a retroactive mockery of Gil Martin speaking in a shellshocked monotone about seeing a friend’s head get blown apart. You can’t insist that war is hell and then turn right around and say “except when it’s hilarious.” And there’s something uniquely undignified about bloodthirsty warriors who are so cowed by a stubborn widow that they turn into moving men. The point at which they agree to help her take the bed downstairs was my “check please” moment, from which the movie never entirely recovered. Those men may have killed half the valley’s population, but they’re no match for a feisty old lady with a sentimental attachment to a piece of furniture. It doesn’t help that one of the Native Americans keeps laughing like a crazed hyena even as he’s struggling to get the bed through the door frame. (Much of the laughter was clearly added in post-production.) Because we wouldn’t want to forget, even for a moment, that destruction is pure fun for these guys. They’re having a blast!

Still, what I’m trying to stress here is that it’s not as simple (or simplistic) as someone viewing a movie made 76 years ago through the lens of today’s (comparatively) enlightened standards. Tarantino’s complete dismissal of Ford, on the basis of a few noxious elements, seems out of character precisely because it’s the kind of overreaction you’d expect from a very different temperament than his. (It’s also worth noting that Ford made a concerted effort to atone for any representational sins during his twilight years, with more progressive films like Sergeant Rutledge and Cheyenne Autumn.) My own problem with Drums Along The Mohawk isn’t that a few scenes are racist. It’s that the racism actively hurts the movie. Appreciating Ford’s work requires making peace with the awfulness and concentrating on the excellence that abounds elsewhere. You know, just like you do when Tarantino appears as an actor in his own movies.