Taylor Negron isn’t exactly himself on this posthumous collection

When comedian and character actor Taylor Negron died back in January, his passing registered with a lot more people than his level of moderate fame might have suggested. Apart from being a fixture in the Los Angeles stand-up scene (as well as his efforts as a playwright, director, and sought-after game show panelist), Negron remains most warmly remembered for his work as a supporting actor in movies and TV. His memorable main villain Milo in the Bruce Willis/Damon Wayans action flick The Last Boy Scout aside, Negron more reliably popped up as one-scene-stealers, his laconic, spacey, vaguely seedy presence making its mark as delivery boys, doormen, waiters, muggers, and unhelpful store clerks. (His memorable turns as seemingly identical, creepy mailmen in Better Off Dead and How I Got Into College suggested a mildly sinister interconnected Savage Steve Holland cinematic universe.)

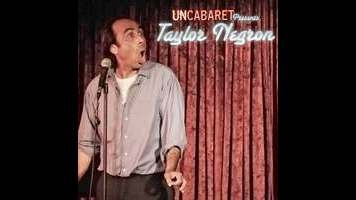

There was something endearingly disreputable about Negron’s comic persona, a louche decadence that hinted at unseemly thoughts but remained diffident about pursuing them. (Repeated anecdotes about his enduring fondness for pot—which he describes as “God saying hi”—suggest context there.) Throughout UnCabaret Presents Taylor Negron, a posthumous collection culled from various sets Negron performed at L.A. alternative comedy club UnCabaret in the late 90s and early 2000s, Negron’s style finds an expansive showcase, even as the formlessness of the enterprise makes for uneven enjoyment.

The background to the album is necessary, as, without it, Negron’s performance through the 14 tracks comes off as unforgivably sloppy. Founded in the late 1980s, UnCabaret requires comedians to abandon their usual material in favor of a looser, more personal storytelling style. As Negron states in the midst of one anecdote early on, “I’m not allowed to do my act up here,” a running theme which goes a long way toward smoothing out the album’s choppiness and inconsistency, as Negron alternates autobiographical stories with brief but entertaining tales from his position on the fringes of the entertainment industry. Negron’s first bit, an extended rumination on L.A.’s improbably beautiful weather, begins with a stammering digression no traditional comedy album would leave in place. Throughout, this formlessness—Negron losing his train of thought, referring to unidentified performers in attendance, or to bits not included in this collection—intermittently saps the comic’s storytelling energy. (Indeed, due to the nature of the album, there’s little opportunity for Negron to build up any rhythm before the individual bit ends.)

What redeems UnCabaret Presents Taylor Negron is, unsurprisingly, Negron himself. At one point, he bemoans the state of his movie career, explaining his decision to accept a stage role in a disastrous production of Dracula by saying, “I don’t wanna be, like, the stupid pizza guy my whole life. I have talent and everyone makes me dance like a monkey on the side.” But Negron’s strongest material here stems from his outsider’s brushes with celebrity, and his attitude toward his career comes off more like an amused delight at being able to tell funny stories about the likes of Willis, Sharon Stone, Jude Law, and others. (The best anecdote is about him getting lost in his Last Boy Scout role and making a particularly unprofessional mistake at the end of his big scene—the only story on the album constructed like a traditional joke.) Here, too, the UnCabaret format leads to a discursive journey through Negron’s life and career—with his verbose delight in language, Negron comes across at times like a less-disciplined Spalding Gray—but for all the digressions and restarts, the comic is always engaging. (No matter which performance Negron’s stories come from, the audience is warmly appreciative, suggesting that seeing these sets live would have been the way to go.)

Negron’s more personal material doesn’t register as strongly, with his laid-back detachment and frequent digressions (and the album’s fractured structure) preventing his anecdotes from building. He talks of the kids in his neighborhood calling him “nigger,” but passes over the fact without suggesting what the experience meant for him. An extended story about his parents offhandedly granting his childhood wish for a monkey elicits a few chuckles, but not the expected hilarity. Similarly, stories about getting arrested for smoking marijuana in Miami, winding up stoned outside Frank Sinatra’s funeral, and attempting to cope with a flood of raw sewage at his house cruise along amiably on Negron’s idiosyncratic charms, but lack the sharp weirdness that made his stand-up unique. That Negron’s performances here are in keeping with UnCabaret’s house style make for a pleasant, if sadly forgettable, farewell to a singular comic talent.