The 17th-century horror of The Witch is troubling on multiple levels

What if the architects and accusers of the Salem witch trials had it right the whole time? What if the women of their community really were in league with the devil, conspiring in black of night and deep of woods? That’s not technically the premise of the new satanic horror film The Witch, which is set in 1630, more than half a century before a group of overzealous puritans put the mark of infamy on their Massachusetts seaport. Still, the events in Salem loom large over the events of the film, like the long shadows of gnarled tree branches. Subtitled “A New England Folktale,” The Witch could be seen as an origin story of American fanaticism—one of the many tall tales that might have inspired a group of young girls to start pointing fingers at their friends and neighbors. Just as easily, however, given the film’s self-advertised stabs at historical accuracy, one could read this singular shocker as something even more disturbing: a kind of fright-flick answer to Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, presenting a revisionist national history in which true evil exists and religious hysteria is the proper response to it.

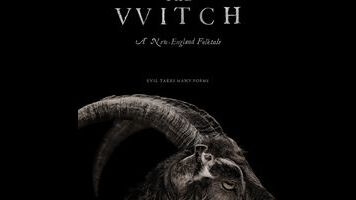

That’s a lot of freight, perhaps, to put on a movie co-starring a demonic ram. But The Witch, like The Exorcist before it, invites serious engagement; to question its implications—historical and religious—is to acknowledge that this is not just some run-of-the-mill exploitation of superstitious fears. As straight horror, The Witch is something special, transporting audiences to a bygone era that would look plenty frightening even without the paranormal activity that engulfs it.

Making an unbelievably auspicious debut—too unbelievable; a Faustian pact was surely forged—writer-director Robert Eggers amps up the unholy menace from the opening frames. Facing banishment, a prideful English farmer removes his family from the comfort of their pilgrim community and heads straight into the surrounding woods. As their rickety wagon makes for the trees, in an ominously protracted long take, the soundtrack swells with anxious strings and a ghastly choir of questionably human voices. The message comes through loud and clear: There will be blood.

“We will conquer this wilderness,” insists the father, William (Game Of Thrones’ Ralph Ineson), as they settle into their new secluded homestead. But misfortune arrives quickly. First, the infant of the family disappears, during an ill-fated game of peekaboo. Then the crops start dying. William’s wife, Katherine (Kate Dickie, another Thrones alum), prays for the soul of their missing child, while pleading with her husband to reverse their exile. Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw), entering the throes of hormonal adolescence, can’t stop stealing glances at the milky exposed flesh of his older sister. And said sister, eldest daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy, a revelation), nurses her own teenage angst, taunting her twin youngest siblings (Ellie Grainger and Lucas Dawson) with fibs about dancing with the devil. Tensions, in other words, run high even before the eeriness begins to escalate.

And boy does it ever escalate. The Witch doesn’t play coy about the nature of the threat; it makes good on its pulpy title. Without quite implying that the danger isn’t real—this isn’t one of those horror movies where it’d be easy to argue that it’s all in the characters’ heads—Eggers preaches hell as other people, augmenting the supernatural material with family conflict. Not that he skimps on the traditional scare fare: There are images, like one involving a ravenous raven, that deposit themselves immediately into the nightmare bank.

Still, more effective than the individual scares—a splash of blood in the milk bucket; an intense exorcism of sorts; the creepiest incognito seduction since The Shining, an obvious influence—is the specific context they’ve been provided. The Witch is a studiously researched period piece, evoking its 17th-century setting through everything from the handmade clothing to the creaky wooden architecture to the archaically formal dialogue, some of which was pulled directly from actual diaries of the period. Even the actors seem to have been selected as much for the old-fashioned severity of their features—enhanced by the natural light of a flickering candle or campfire—as for their comfort with the vernacular. By placing old tropes in an even older world, Eggers somehow makes them feel new again. The familiar becomes chillingly unfamiliar.

Then again, it’s that very commitment to environmental authenticity that makes The Witch so troubling, and not just in the way it intends. A postscript proudly boasts of the various historical accounts that Eggers consulted, all in the interest of meticulous realism. Which is to say, this is a movie that situates itself very purposefully in an actual time and place; it doesn’t require some huge mental leap to connect its fictional terrors to the very real ones inflicted upon a group of innocents in the same geographic region about six decades later. Is The Witch a vivid portrait of theological paranoia, showing a small community torn apart by its irrational suspicions? Or is it a cautionary tale about a family of Christians who leave the church, only to discover that such unfounded fears actually aren’t unfounded? Eggers seems to want it to be both, but the result is a horror movie that comes dangerously close to showing sympathy for the real devils, the kind that burned witches instead of instructing them. Good thing it’s scary.