The 25 best set pieces of Steven Spielberg’s career

Our list is chronological, which means that it traces Spielberg’s own development as a filmmaker

Broadly defined, a set piece is a thriller within a film, a self-contained showstopper-slash-showcase whose success depends in large part on a director’s chops. Since the 1970s, Steven Spielberg has reigned as its Hollywood master; regardless of what one thinks of his sentimental or narrative instincts, it’s hard to deny that the man knows spectacle. With Ready Player One—a film that quotes and riffs on dozens of memorable movie moments and monsters, including some of the director’s own work—hitting theaters this week, The A.V. Club has decided to pick 25 of Spielberg’s best set pieces.

Our list isn’t ranked, but chronological, which means that it inevitably traces Spielberg’s own development as a filmmaker, evolving from purely thrilling and awe-inspiring set pieces into darker and more ironic territory. And it should go without saying that, while some of his most entertaining films ended up with multiple entries on our list, not every one of Spielberg’s best movies contains a spectacular set piece (Catch Me If You Can doesn’t, for example), and that not all of his best set pieces are in his strongest films.

Spielberg’s first theatrical release is basically a two-hour car chase following escaped convict Clovis (William Atherton); his wife, Lou Jean (Goldie Hawn); and eventually a police officer named Ernie (Michael Sacks). As the trio makes its way through rural Texas, they’re pursued by an unwieldy assortment of law enforcement from various municipalities, all gunning to catch the famous couple and barely coordinating with each other to do it. At one point, all of the officers make a temporary headquarters at a small football stadium. When some loose-cannon civilians spot the trio at a used-car lot and open fire on them, the officers at the stadium head to their squad cars. From the air, the camera follows a couple dozen cars barreling out of the parking lot, sirens flashing, many speeding across the lawn to get to the road. [Kyle Ryan]

This is where it all truly began. Spielberg had impressed with earlier films, but Jaws is where his ability to, well, drop jaws finally captured the world’s imagination. The opening minutes set the blueprint for future blockbusters, establishing the “hook ’em right away” strategy practiced by nearly every big-budget Hollywood movie since. A young woman named Chrissie breaks away from a beach party, tailed by a drunken paramour hoping to join her for a skinny dip. Instead, he passes out, and what happens next is the stuff of nightmares: After a few establishing shots of her swimming, and the ominous underwater movement of the camera, Chrissie is suddenly yanked down—and then, as she begins screaming, we watch her pulled back and forth across the surface, her shrieks becoming increasingly awful (“It hurts!”), until she disappears for good. The only cutaways are to a silent, static shot of the guy passed out on the beach, a mute counterpoint to the horror lurking under the water. It’s still one of the most attention-grabbing openings in film history, and one of the creepiest. [Alex McLevy]

Like E.T., the aliens who visit Earth in Close Encounters are friendly—Spielberg wouldn’t tackle an extraterrestrial threat until 2005’s War Of The Worlds—but you wouldn’t guess that from their stop in Muncie, Indiana. For several nightmarish minutes, single mom Jillian Guiler (Melinda Dillon) and her 3-year-old son, Barry (Cary Guffey), experience a full-scale assault in their isolated farmhouse, as several UFOs descend from roiling clouds and make a concerted effort to force their way inside. Spielberg orchestrates the mounting mayhem brilliantly, juxtaposing screams and loud noises with quietly sinister touches, like a heating grate’s screws unscrewing themselves and clinking to the floor. (He also uses Johnny Mathis’ “Chances Are” as ironic counterpoint, long before that move became a horror-movie cliché.) But what’s most disturbing about the sequence is the way that Jillian’s sheer terror bounces off of Barry’s utter delight. “Toys!” he cries out when he sees the lights in the distance, instinctively understanding that they mean him no harm. The shot of Barry standing in the house’s front doorway, looking out at a landscape bathed in eerie yellow-orange light, is among the most iconic in Spielberg’s entire filmography. [Mike D’Angelo]

Spielberg’s World War II farce 1941 isn’t exactly fondly remembered—or remembered at all, really, except by curiosity seekers investigating the director’s sole foray into full-blown comedy, and Eddie Deezen, perhaps. But while the movie is mostly known for being a flop (although it wasn’t) and for a cast drawn from vintage SNL and SCTV players, there is one scene that’s achieved its own legacy: the Japanese submarine attack on an amusement park, which ends with an enormous Ferris wheel rolling into the ocean. Made in a pre-digital effects era, it’s an impressive work of miniatures; the lit-up wheel, the pier, and an entirely realistic, glowing carnival were all constructed around a water tank, while the crew had just one chance to nail the shot as their wheel wobbled its way into the drink. Spielberg maintains the illusion by deftly crosscutting between the spinning wheel and its frantic passengers—Jaws’ Murray Hamilton, Deezen, and Deezen’s ventriloquist dummy—as they’re being whipped around. It’s a truly spectacular moment, and almost powerful enough to make 1941 seem like a better movie than it is. Almost. [Sean O’Neal]

Despite the success of Jaws and Close Encounters, Steven Spielberg’s name hadn’t quite become synonymous with “must see” in 1981. Raiders Of The Lost Ark was far from a sure thing, in other words, even though it starred the other guy from Star Wars. The success of the entire movie, and the Indiana Jones franchise, depended on that perfect, all-important initial action sequence, in which Indy tackles a multitude of obstacles—poison darts, gaping chasms, a giant boulder, and finally, a (benign) snake in his lap—to obtain a small golden idol from a heavily booby-trapped temple. What makes Indy so immediately endearing is that he fails as often as he succeeds, giving his hat a swaggery swipe when he thinks he’s fooled the temple, only to get attacked immediately, and barely sliding under the door that would imprison him for all eternity. He even loses the idol—but hooks enough viewers to become a legend in about six minutes. [Gwen Ihnat]

It may not feature the iconic, “one perfect shot” moments of the rousing opening or gruesome climax, but the mid-film truck chase in Raiders Of The Lost Ark is beat for beat arguably the most thrilling of all three. It’s one of those signature Spielberg set pieces that’s just one thing after another. From the instant Indiana Jones hops on a horse and takes off after the Nazis to the moment he secures the truck containing the ark of the covenant and drives it into the hiding space (and a flood of townsfolk rush to disguise the entrance), the director and his adventurous main character haven’t a second to catch their breath. Spielberg knows exactly where to place the camera at every moment for maximum thrills; even when he’s pulling back for a wide shot to show a few German stooges go flying off the side of a cliff, it feels viscerally intimate. Still, it’s the little moments, like the momentary smirks that flash across Harrison Ford’s face after dispatching a goon, that help make this chase sequence a standard against which all future demonstrations of his action-movie bravura can be judged. [Alex McLevy]

More than a decade before Spielberg The Grownup Filmmaker plunged audiences into the full horror of the Holocaust, Spielberg The Ageless Adolescent tackled history’s darkest chapter from a more boyish, innocently rousing vantage. Raiders Of The Lost Ark is all about sticking it to Hitler—a kind of fantasy score-settling that culminates in the film’s karmic, cathartic Grand Guignol climax. Tied to a nearby post, Ford’s Dr. Jones and Marion Crane (Karen Allen) avert their eyes as the Nazi bad guys pry open the titular artifact and get some supernatural comeuppance. The ethereal effects look primitive by today’s standards, but there’s a timeless (and, sadly, rather timely) thrill to watching these Third Reich scoundrels go from solid to liquid for their sins. It was neither the first nor the last time Spielberg would push the limits of the PG rating; everyone tends to attribute the introduction of PG-13 to the heart-ripping violence in his second Indiana Jones movie. But with Raiders, Spielberg traumatized all ages for a greater good. Remember, the next best thing to clocking a real Nazi is melting off the face of a fake one. [A.A. Dowd]

In keeping with its story of an alien taking shelter in the suburbs, much of E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial keeps things more or less tethered to the earth. A few levitating balls, some revived dead flowers, and a glowing finger aside, for much of the film, E.T.’s otherworldly powers are played small—which only makes the moments where they’re finally, truly unleashed all the more magical. The first such instance, when E.T. telekinetically levitates Elliott’s bicycle across a moonlit sky, instantly became such an icon of adventure that Spielberg adopted it for his Amblin Entertainment production company logo. Even more impressive, Spielberg redoubles it with a reprise in the movie’s big climactic escape sequence, which volleys from the back of a stolen van to a fleet of kids’ bikes without ever breaking stride, before E.T. boosts Elliott and his friends up over a squad of cop cars and into the skies. In that one, triumphant moment, buoyed by John Williams’ soaring score, E.T. achieved its own liftoff—and sold a million BMX Kuwaharas besides. [Sean O’Neal]

Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom makes up for its slow start in its thrilling back half, where Spielberg stages one breathless action sequence after another. Lounge singer Willie Scott (Kate Capshaw) is nearly toasted in a cult ritual; Indy and Short Round (Jonathan Ke Quan) free an army of child slaves; the trio goes on a runaway cart ride before being washed out of the mines and onto a rickety rope bridge where Indy faces a final confrontation with the cult leader. Spielberg pauses the action for long moments of suspense, backed by an agitated drumroll as Indy contemplates his situation. The tense standoff provides the film with one of its most striking images: the silhouette of the archeologist in the middle of the bridge, machete raised, as the enemies on either side inch closer. The suspense gives way with the snap of the rope as Indy hacks it to bits, sending cultists to the hungry alligators waiting in the water below. A fist fight on the side of the cliff ensues, but its those moments on the bridge, almost unbearably tense, that put a punctuation point on the film’s rousing culmination. [Caitlin PenzeyMoog]

Spielberg’s 1987 drama follows a young boy named Jim (a prepubescent Christian Bale) in World War II China, where’s he’s separated from his parents and imprisoned in an internment camp. Before war breaks out, Jim and his parents hole up in a hotel with other moneyed foreigners. The film’s first big set piece begins when Japanese warships start attacking. As Jim and his family get outside, they find streets packed with panicked locals but manage to reach their car—until they get stuck in traffic, and a Japanese tank begins crushing cars behind them. Jim and his parents join the hundreds of people fleeing in the streets as dozens of Japanese warplanes fly overhead. Jim and his mother are first separated from his father, then each other. As Jim stands on a cart and screams for his mother, the Chinese guerrillas on nearby rooftops open fire on Japanese soldiers marching in the streets, and Jim finds himself not only without his parents but in the middle of a gun battle. [Kyle Ryan]

Even after all the slam-bang plane-and-train chases that precede it, the climactic set piece of Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade qualifies as an adventure unto itself. After arriving at the Temple Of The Sun, Indiana Jones must pass through three mystical booby traps to find the Holy Grail in order to heal his mortally wounded father (Sean Connery)—a sort of “final level” that sees Jones deciphering cryptic clues in order to dodge decapitating blades, jump across crumbling tiles, and take a literal leap of faith over a canyon. It’s there he must complete his last and most difficult challenge: to “choose wisely” from a collection of potential Grails that could give its bearer immortality, or instant death. The temple sequence adheres to its own three-act structure of suspense, which Spielberg heightens with cross-cuts back to a dying Connery, muttering advice to his son. And it captures everything great about Indiana Jones—his cunning, his daring, even his archaeological smarts—in one gripping vignette. [Sean O’Neal]

“Oooh, ahhh, that’s how it always starts,” Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) deadpans in The Lost World. “Then later there’s running and screaming.” He’s reminiscing, really, about the moment in the original Jurassic Park when the awe of laying eyes on a dinosaur morphs, with a shiver, into a primal, gaping terror. The attack on the jeeps in the rain is maybe the scariest five minutes of Spielberg’s career, because it locks you into the physical and emotional crucible of the characters. The scene plays out without a note of music and through a carefully selected collection of iconic, unforgettable images: the ominous ripple of water in the plastic cup; the lamb’s leg landing with a wet thud on the sunroof; the contracting eye of that mighty, almost feline Tyrannosaurus, which Spielberg brings to life through a seamless, still impressive mixture of animatronics and early CGI. The sequence’s best effect is the credible dread transmitted by the puny, captive human prey—the young kids cowering from the gnashing jaws of prehistoric history, and the adults paralyzed by fear one vehicle over, watching voyeuristically as Malcolm’s theories about an uncaring universe become nightmarishly less than theoretical. [A.A. Dowd]

The first words of the raptor scene are these: “It’s inside.” Lex is wrong though: There are actually two raptors in the room, one to kill her and one to kill her brother. There’s a terrifying intimacy to the scene, which follows a pair of walking, hyper-intelligent meat cleavers as they try to disembowel a couple of adorable children. Of course it’s set in an industrial kitchen, with its icy, gleaming counters, its impassive meat locker, its evocation at once of comfort and butchery. Spielberg films it all from the kids’ point of view, in part to obscure the very human legs of the people in the raptor suits, but it’s a bind he works with his typically masterful staging, constantly finding new right angles to send the kids (and the camera) scrambling around. So many of Spielberg’s best moments come from his understanding of the narrative potential of horror, particularly when it rears its birdlike head unexpectedly. With Jurassic Park’s kitchen scene, he packs the awe and spectacle seen elsewhere in the film into a tiny space, creating a pulsing heart of slasher-flick terror the rest of the film merely implies. The adorable children, of course, end up fine. [Clayton Purdom]

Remarkably released in the same calendar year as Jurassic Park, the black-and-white, Oscar-feted Schindler’s List is widely considered the moment when Spielberg officially completed his transformation into a Serious Director, putting down his toys to tackle the unfathomable tragedy of the Holocaust. But the same wizard of kinetic movement and immersive spectacle is still there behind the camera, and in the drama’s centerpiece sequence (merely excerpted above), he marshals all his powers to bring history to gut-wrenching life. Recreating the horror of March 13, 1943—when the SS liquidated a Krakow ghetto, murdering some 2,000 Jewish occupants and forcefully relocating as many more—Spielberg offers a panoramic portrait of humanity’s capacity for evil, crosscutting from one atrocity to another, depicting the invading squadron as a single-minded force of destruction as uncaring as the organic death machines of Jaws and Jurassic Park. As with most of Spielberg’s best sequences, it all comes down to perspective: As the scene’s 15 numbing minutes grind on, we cut to Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson) watching from above, his conscience violently stirred, and then symbolized by a single, innocent figure in red, shining brightly against the cold gray slaughter. [A.A. Dowd]

It sounds like mindless sequelizing: The most famous sequence from Jurassic Park featured a T. rex, so why not bring out two T. rexes for The Lost World? But when a pair of dinosaur parents come searching for a baby that foolish humans Jeff Goldblum, Julianne Moore, and Vince Vaughn are aiding in their trailer, Spielberg feints toward anticlimax. The scientists simply give the baby back, which seems like a great solution until the parents seek revenge by knocking the trailer over the edge of a cliff. With the pitiless showmanship that characterizes the best parts of The Lost World, Spielberg nimbly puts his characters through the wringer, diabolically moving from Moore balanced on a slowly cracking pane of glass, to the dinosaurs triumphantly collaborating to tear poor Richard Schiff in twain, to the trailer finally going over the cliff around the ascending heroes. It’s not as famous as several bits from the first Park, but its delightfully sustained tension was knocked off as recently as this year by the Tomb Raider reboot—minus the dinosaur-related carnage, naturally. [Jesse Hassenger]

Viewers had never seen such graphic violence in a prestige Hollywood production, or really in a war movie at all. But the impact of the protracted battle scene that opens Saving Private Ryan, in which Spielberg plunks the audience down on blood-soaked Omaha Beach circa June 6, 1944, can’t be reduced to the mere shock of its limb-severing, entrails-exposing carnage. Shot in a queasy, you-are-there handheld that would quickly become the new cinematic standard for depicting warfare on screen, this 20-minute spectacle of blinding panic—deceptively chaotic, but carefully orchestrated, as only a master technician like Spielberg could—tosses out decades of combat-movie cliché, redefining heroism on the frontlines as simply daring to keep moving forward through the fray, when every second exposed puts you in death’s crosshairs. The sequence’s canniest trick is bonding us to Saving Private Ryan’s central band of brothers through forced identification; having seen the hell of Normandy through their eyes, we feel as close to them as they do to each other. [A.A. Dowd]

The Flesh Fair, a cross between auto-da-fé and a monster truck rally presided over by the demagogic carnival barker Lord Johnson-Johnson (Brendan Gleeson), is both the most fairytale-like sequence in Spielberg’s sad, thoughtful masterpiece and the grimmest—the film’s themes summarized in one grotesque carnival. Captured along with a group of obsolete domestic “mechas,” the Pinocchio-esque android boy David (Haley Joel Osment) watches as disturbingly humanized robots are demolished before a roaring crowd. The director subverts his trademark childlike awe into pure childhood nightmare fuel; even the sequence’s sentimental conclusion can’t shake its hopeless view of humanity. Like so many of the most breathtaking set pieces in Spielberg’s mature body of work, the Flesh Fair uses his command of spectacle and viewer sympathy to extrapolate a dark point. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

The first few minutes of Minority Report give us an extraordinary amount of information, so much so that we’re able to track a fairly complicated futuristic “Precrime” society even before the requisite explanatory video. Spielberg accomplishes this by using two distinctive palettes: The Precrime lab is in blue, the crime-about-to-happen is in a sepia tint of brown, evoking instant nostalgia for an on-the-surface typical domestic scene that is about to be ripped to shreds. Meanwhile, we get the same tour of the pre-crime lab that Department Of Justice visitor Danny Witwer does: a quick introduction to the pre-cogs, their visions, and the red balls that indicate future murderers and their victims. Then Tom Cruise’s Precrime chief, John Anderton, really goes to work, isolating images from the pre-cogs’ visions on a translucent screen to find out where the crime is taking place only a few minutes into the future, reduced to clues like a public park and cops on horseback. The Precrime team stops the murder by dramatically invading the heartbreaking marital crime scene and melding the two worlds together. By the end of the sequence, we’re as on board with Precrime as 2054 D.C. is. [Gwen Ihnat]

Spielberg’s B-movie-influenced adaptation of the H.G. Wells classic is above all a first-rate set piece machine, combining the director’s peerless command of point of view with some of his most darkly surreal imagery in panicked stretches punctuated by the most influential sound effect of the 2000s: the rumbling, didgeridoo-like alien foghorn. For pure tension and chaos, it’s hard to beat the first appearance of the alien tripods. Wandering down a street of mysteriously disabled cars, the movie’s Jersey longshoreman hero (an unlikely Tom Cruise) joins a crowd around a growing sinkhole. An extraterrestrial war machine emerges from the ground, unleashing death rays that vaporize scrimmaging pedestrians into puffs of gray cremains. Countless sci-fi blockbusters have toyed with the iconography of 9/11; this is the only movie that’s done it well, drawing the feeling of the morning-of into a drive-in movie about arbitrary, traumatically inexplicable terror. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

Spielberg’s War Of The Worlds is an unrelenting, brutal fight for survival, made even bleaker by the fact that the humans accomplish no victories at all; the aliens are felled by the dumb luck of being allergic to the Earth’s atmosphere. Until those red vines turn white, though, there’s plenty of anguish, never moreso than in WOTW’s ferry sequence. It’s all the more painful because the night-drenched scene offers a moment of solace: The friendly captain urges everyone on board, saying there’s plenty of room, and it seems that Jack (Cruise) and his kids (Justin Chatwin and Dakota Fanning, dubbed “most useless thing to have in an apocalypse” by MTV) have finally found a momentary respite. Even the song in the background, Tony Bennett singing the ironic “If I Ruled The World,” seems to indicate a haven. But a flock of hastily fleeing seagulls hints that this security is false. One of the aliens’ tripods sends out that now-familiar hideous-sounding alarm, and the scene instantly turns from benevolent to frantic; Spielberg seems to be aping Titanic here, if the ship hit a giant, menacing alien instead of an iceberg. Cars hit the water and Jack and his kids somehow make it to shore, but safety seems further away than ever. [Gwen Ihnat]

A study in elaboration and tension, Spielberg’s darkest film choreographs an unbelievable number of zooms, pans, frames-within-frames, reflections, cuts, and changes in point of view into a danse macabre of split-second timing, stoking nail-biting suspense as it draws the audience deeper and deeper into the moral uncertainty of a group of Mossad agents tasked with hunting down and assassinating a network of Palestinian militants in the aftermath of the disastrous 1972 Olympics. Having planted a bomb under a phone in its second target’s Paris apartment, the team takes its places, only to have the man’s young daughter answer the call. Out of all of Spielberg’s mature works, Munich represents the most perfect fusion of technique and theme: Scrambling to call off the remote detonation, the agents are in large part racing to preserve their own supposed moral high ground; the little girl is only a prop. The blast of the bomb shredding the “right” target makes for a sobering punctuation. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

Spielberg had yearned to translate Hergé’s long-running Tintin comics to the big screen for decades, and he finally realized it in 2011 with the help of (deep breath) Kathleen Kennedy, Peter Jackson, Steven Moffat, Edgar Wright, and Joe Cornish. The result is… well, nobody’s favorite work from the director, but the collaboration with Jackson’s effects team, Weta, allowed him to pull off some truly outrageous set pieces. The high point is a chase scene in which half the film’s characters go hot-rodding after one or another of the film’s MacGuffins, plucked into the air by a villainous falcon. But thanks to the CGI format, most of the chase is staged in a breathtaking, unbroken two-and-a-half-minute shot. Spielberg throws everything in: tanks, collapsing buildings, waterfalls, motorcycles, fisticuffs, wisecracks, rollercoaster dips along electrical wires, seamless shifts between points of view, and a death-defying slow-motion leap to safety. It’s tempting to compare it to some of the director’s other long-take action scenes, like those in War Of The Worlds, but it feels much more like his long-simmering video-game ambitions realized, rendering a dense cityscape into an explosively choreographed obstacle course. [Clayton Purdom]

Given its lush Old Hollywood frame of a boy and his beloved horse, War Horse isn’t exactly known as a thrill-packed Spielbergian roller coaster. But once Joey the horse is sold into World War I and makes his way from owner to owner, the movie’s episodic structure lends itself well to Spielberg’s facility with memorable shots, sequences, and set pieces. The best of these comes in its final stretch: After following the horse’s faithful owner through a brutal trench-warfare battle, Spielberg cuts over to Joey, also in the trenches, hauling artillery for the Germans. When Joey flees a tank, he leaps over trenches and dashes through No Man’s Land, Spielberg capturing the kineticism of his pure animal fear (and drive to survive). After the horse gets tangled in barbed wire, an Englishman and a German each brave the desolate battlefield to help, even making small talk over their task. It could be cornball—this horse-besotted movie is far from Spielberg’s hippest—but he shoots both the action and the quiet time-out with stunning beauty, pulling the camera back on the scene as the two soldiers depart, chasing the horror of war with tenderness, then distance. [Jesse Hassenger]

It’s not easy to generate excitement and suspense from a roll call vote of over 200 congressmen, especially when viewers already know the outcome. That’s the challenge accepted by Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner in Lincoln, which climaxes with the House Of Representatives’ final vote on the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery in the U.S. There’s a bit of comic urgency early on, with certain factions calling for postponement and James Spader’s arm-twisting operative running frantically from the Capitol to the White House in order to secure an expedient falsehood from the president. Mostly, though, the tension derives from our knowledge, based on previous scenes, of which Democrats have been pressured and/or bribed into reluctantly crossing party lines; there’s no doubt that they’ll vote “aye”—this is Spielberg, not Tarantino—but every pregnant pause after a name is called works anyway. Maybe it’s just the momentousness of it all. At the end, Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax (Bill Raymond) expresses a desire to cast his vote, even though doing so, as the opposition reminds him, would be highly unusual. “This isn’t usual, Mr. Pendleton,” Colfax solemnly replies. “This is history.” [Mike D’Angelo]

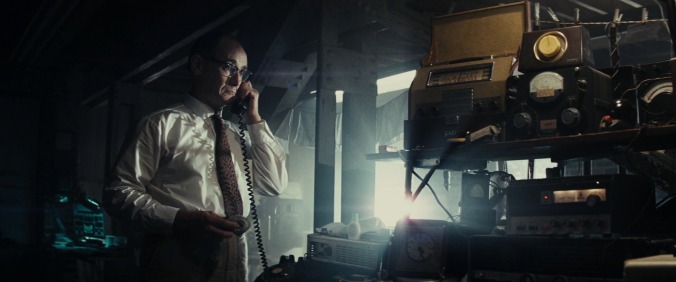

A master of humanizing performance meets a master of spectacle in the largely wordless and terrifically suspenseful opening sequence of the Cold War drama Bridge Of Spies. Long hailed as one of the world’s greatest stage actors (and arguably its finest Shakespearean), the unostentatious, bushy-browed Mark Rylance had only a sporadic film career before he was cast as the Soviet spy Rudolf Abel. From the opening shot, Rylance’s rumpled performance and Spielberg’s dramatic camerawork (emphasized by the rare use of anamorphic widescreen, a format the director had mostly abandoned after the early ’80s) conspire to keep the viewer gripped and intrigued as Abel goes about his day in late ’50s New York, pursued through the streets and subways by a group of FBI agents. Relying on composition and editing instead of the elaborately cued zooms and camera movements that characterized Munich, the sequence showcases Spielberg’s expert choreography of basic film grammar—and makes a delightfully ironic prologue to a film about bloviating rhetorical flourishes and doublespeak. Unsurprisingly, Rylance (who won an Oscar for his performance) has appeared in every Spielberg film since. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)