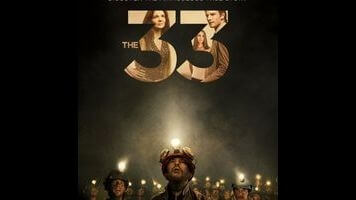

The 33 is kind of like The Martian, only terrestrial and dull

Five years ago, 33 men were pulled, one by one, out of a gold and copper mine in Chile after a mountain literally fell on them, stranding them several hundred meters underground for more than two months. The 33, the major motion picture that’s been made out of this extraordinary ordeal, arrives as a sort of buried-alive companion piece to The Martian—a nuts-and-bolts rescue mission during which the majority of the ensemble struggles to keep the faith against long-shot odds. Set in an Atacama Desert where everyone talks in English (a newscaster is the sole Spanish speaker), the movie certainly hasn’t been streamlined into The 7 or The 8. In addition to the few-dozen miners, led by “Super” Mario Sepúlveda (Antonio Banderas), The 33 spends significant time with the folks aboveground at Camp Hope, where the country’s telegenic minister of mining (Rodrigo Santoro) coordinates efforts to save those trapped by the cave-in, and a hotheaded maker of empanadas (Juliette Binoche), her partially estranged brother buried below, serves as a mouthpiece for the affected citizens of Copiapó.

The film—directed by Patricia Riggen and dedicated to late Titanic composer James Horner, who wrote the score—drills right along, but it seems unsure of which members of its grab-bag cast to focus on at the expense of others. In the stygian recesses of the mine—which are well rendered here, the metal-embedded diorite glinting in the light of the headlamps, giving the place an eerie night-sky glimmer—the foreman (Lou Diamond Phillips) makes it very clear that he takes everyone’s safety seriously, the boozer brother of Binoche’s character (Juan Pablo Raba) undergoes what appears to be delirium tremens, and Oscar Nuñez (who played Oscar on nine seasons of The Office) takes some good-natured ribbing for being henpecked by two women at once. On day 3, the prospect of cannibalism makes for a tastes-like-chicken joke among the men, and by day 14, Super Mario is able to dismiss it once and for all (“Nobody’s eating anybody while I’m here!”), even though they’re all down to their last can of tuna. The activity on the surface, where no one knows until day 17 if the miners are even alive, takes on a lot more urgency. Gabriel Byrne’s engineer appears as if out of nowhere, advising Santoro’s suit on the best way to access the pit’s refuge, where the men have congregated. Meanwhile, Shawshank warden Bob Gunton—who plays President Sebastián Piñera, concerned that the fate of his administration lies with that of the miners—speaks haltingly, plying the most mystifying accent of all.

Stalled in management mode for much of its duration, Riggen’s film nonetheless has its solid elements, one of them being Banderas’ energetic lead performance. Mario guards the food supply and occasionally gets up in his fellow miners’ faces to make one impassioned case or another, but his story also winds up feeling dramatically diluted—having introduced his wife and daughter in its opening sequence, the film declines to make much subsequent use of them at all. Even that time-honored tradition of true-story-derived cinema—the pre-credit unveiling of the real-life subjects—feels miscalculated here: Cinematographer Checco Varese captures the 33 in silky black-and-white, as they enjoy a slo-mo banquet on a beach, before each takes his turn on-screen next to his name. More than anything else, the sequence resembles the false idyll of a pharmaceutical ad, but one intent on outlasting its allotted 30 seconds. There is light at the end of the tunnel, though. During the roll call, most of the miners laugh and smile—it almost looks like they’re relieved, too, that the movie is wrapping up, however slowly.