The 35 best science-fiction movies since Blade Runner

The most widely admired science-fiction film to come out of the 1980s, Blade Runner reimagined the nocturnal, seductive, and pessimistic qualities of film noir and its ’70s derivative, neo-noir, for the paranoid cityscape of the future: a dark, rainy, multi-lingual Los Angeles where a detective in a trench coat trails a gang of biomechanical replicants who escaped from an off-world colony. Released during a rich period for sci-fi, fantasy, and special-effects filmmaking—the same weekend as the sci-fi horror classic The Thing, just two weeks after E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, with Star Trek II: The Wrath Of Khan, Conan The Barbarian, and Poltergeist still in theaters—it was not initially a hit. But over the last 35 years and across multiple reedited re-releases, Blade Runner has grown exponentially in stature and influence, and and now looms over the genre, second only to 2001: A Space Odyssey.

With a belated sequel, Blade Runner 2049, opening in theaters this Friday, we at The A.V. Club couldn’t help but ask: What are the best sci-fi movies to come out since the original theatrical release of Ridley Scott’s masterpiece? Of course, some parameters had to be created, because the question of what is and isn’t sci-fi can become very tricky. Some movies are grandfathered in by venerable sci-fi tropes like time machines, space travel, artificial intelligence, dystopian societies, or extraterrestrial and extra-dimensional life. But is a story that revolves around pseudo-scientific gobbledygook any different from a story about magic? And why not include superhero movies, which more often than not involve sci-fi elements?

Our list kicks off with what might be its most controversial entry. The costliest and, in retrospect, unlikeliest project of David Lynch’s career, this singular space opera is set in a feudalistic deep future where aristocratic dynasties plot over the mind-altering resources of a desert planet. Kyle MacLachlan, who would become Lynch’s iconic leading man in and , stars as the heir of a noble house who leads the planet’s native inhabitants in a rebellion, though his hero’s journey is lost in the film’s tapestry of conspiracies, accents, Freudian overtones, tsarist trappings, and creepy drones. By turns bombastic and grotesque, campy and fatalistic, Dune has to be the most subconsciously strange film to ever try to pass itself off as special effects blockbuster—less an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s classic 1965 novel than an obfuscation. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]When one of dystopian literature’s cruelest suppressions of youthful unrest made it to the big screen, it was condemned by Japanese parliament and shunned by North American distributors. But whether they waited for a legal means to see the students of class 3-B pick each other off one by one or risked acquiring their own explosive collar by seeking out a bootleg, American audiences would learn that Kinji Fukasaku’s futuristic bloodbath lives up to its reputation. Everything feels like life or death in high school, and Battle Royale inflates those feelings to allegorical proportions, a twisted test of loyalty and survival that’s part Lord Of The Flies, part The Most Dangerous Game, and part media critique à la The Running Man. Nearly impossible to see for more than a decade, the film still managed to influence blockbuster franchises () and its fellow future midnight features (), though perhaps its greatest impact is in making a crackerjack sci-fi picture out of the sneaking, teenage suspicion that everything and everyone is set against you. [Erik Adams]

Duncan Jones earned a richly deserved BAFTA for his 2009 debut, a throwback bit of hard sci-fi about a lone astronaut who spends his days mining the lunar surface for a massive corporation, and his nights building models, arguing with his robot buddy (Kevin Spacey, providing a 21st century, emoji-equipped answer to Hal 9000), and pining for the family he left back on Earth. But shortly before Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell) is scheduled to go home, an on-the-job accident permanently disrupts his monotonous routine, and Moon soon finds itself spiraling into a much weirder direction. Like all the best sci-fi, Jones’ film asks questions that we’re not yet equipped to answer, the big, heady stuff about who we are, where we’re headed, and how much damage we’re going to do to ourselves along the way. It’s also a fantastic showcase for Rockwell, who somehow manages to make driving a giant truck across the stark, gorgeous stillness of the lunar surface look like just another boring goddamn job, while simultaneously working through the steps of a serious existential freak-out without ever descending into hysterics. [William Hughes]

Science fiction is often rife with dense mythologies, but rarely is the mythology more casually dense than in The Adventures Of Buckaroo Banzai Across The 8th Dimension. W.D. Richter’s madcap debut follows the eponymous neurosurgeon/test pilot/rock star (Peter Weller, cool as all hell) as he defends Earth from an inter-dimensional alien takeover. But the plot couldn’t be more beside the point. Taking their cues from a variety of high/low pop culture—The Fantastic Four, Thomas Pynchon, Orson Welles, ’70s kung fu, Elvis Costello—Richter and screenwriter Earl Mac Rauch create a complex world and then have the confidence never to over-explain it, instead allowing viewers to comb through the thicket of gags on repeat viewings. What really keeps them coming back is the generosity of spirit baked into everything from the performances to the intricate production design. It’s a wacky ride to nowhere and everywhere at once. [Vikram Murthi]

This isn’t the first time The Host has crashed a decades-spanning A.V. Club list. Two years ago, it made like a rampaging mutant river monster and plowed its way into our ranked rundown of the . Truth is, this exhilarating budget blockbuster—Spielbergian in both its focus on fatherhood and its tremendous special effects—is no more easily classified than the film’s ferocious star attraction. The basic premise is science (runs amok) fiction: an eccentric makeover of atomic-age anxieties. But South Korean visionary Bong Joon-ho juggles multiple tones and genres, stuffing a seriocomic family portrait down the gullet of a throwback kaiju movie, then dousing the whole thing in withering social critique. In other words, though The Host helped put Bong on his current path to sci-fi canonization (see: two films down from here), don’t be shocked when it breaks the top 20 of next year’s list of, say, the best political satires since Being There. [A.A. Dowd]

29. (2013)In Bong Joon-ho’s Snowpiercer, the remnants of humanity pack tightly into train cars, where “first-class passenger” has taken on a new meaning. Uprisings are a common occurrence, but they’re brutally suppressed. Though there’s really only one way out of this dystopian nightmare, there’s nothing straightforward about Bong’s vision. The director of The Host takes a French sci-fi novel, filters it through some of the genre’s best films, including Aliens and Brazil, and then reimagines capitalism’s rat race as a never-ending train trek. Parallels are easy to draw, but Bong and co-writer Kelly Masterson’s class-warfare parable is unlike any other, in part because the character development is as plentiful for the have-nots as it is for the haves. The result is equal parts grimy fable and post-apocalyptic action movie, powered by a soulful lead performance by Captain America himself, Chris Evans. [Danette Chavez]

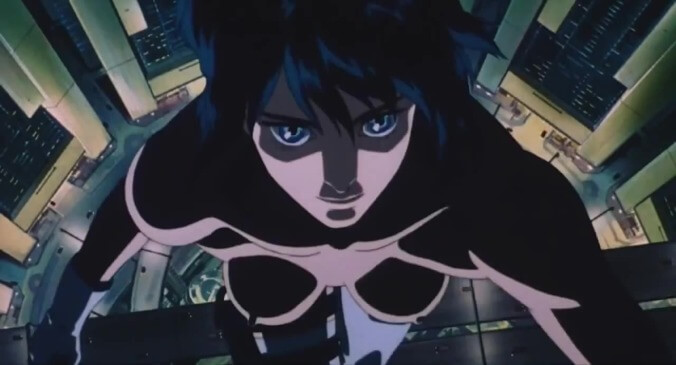

You’d be forgiven for thinking that the stars of Ghost In The Shell were its various lovingly animated machines: enormous mechanical firearms, boxy cars and helicopters, intricately locking steam-powered doors, and blinking UX displays full of hallucinatory information. Its humans, meanwhile, often remain static for whole scenes, barely blinking; you never even see Batou’s eyes. Mamoru Oshii’s cyberpunk masterpiece explores a world in which the lines between human and machine are increasingly blurry, but it has a clinical, almost procedural air, with the bureaucratic intrigue and moody, neon-lit nightscapes of a Michael Mann film. Thanks in part to the vast fictional universe from which it hails—which has resulted in several excellent sequels, games, and the rare that doesn’t ruin everything—this seminal anime manages to couch its transhumanist musings in a narrower noir narrative. In the same year that also brought sensationalist, like Hackers, Johnny Mnemonic, and The Net, Ghost In The Shell manages to render the digital infosphere at once mundane and liberating, an agent of change to be anticipated, protected, and exploited. [Clayton Purdom]

Disregarding , Richard Kelly’s debut is less of a straight science-fiction film than a metaphysical meditation on teenage alienation, on that feeling like neither you nor anything you do matters. In his breakout role, Jake Gyllenhaal uses his haunted eyes to their greatest effect as the titular troubled kid, living in an anonymous late ’80s suburb, where he’s plagued by nightmarish visions of a man in a rabbit costume, ominously counting down to the apocalypse. Kelly’s film creates a sustained mood of dreamy portent, full of Lynchian surreality, eerily calm silences, and some of the best use of gloomy new-wave ever committed to celluloid. But Donnie Darko also leavens these with moments of absurdist black comedy (never doubt its commitment to Sparkle Motion) as well as a surprisingly moving story about a family trying to cope with mental illness. It’s a uniquely soulful work, one that just happens to involve wormholes and demon bunnies. [Sean O’Neal]

The brilliant low-budget sci-fi action flick that launched James Cameron’s career begins its mirror dance of destruction and destiny with a tank-bot crushing human skulls in a post-apocalyptic wasteland and two nude figures materializing from blobs of animated lighting in mid-1980s Los Angeles. One is a human soldier (Michael Biehn) thrown back in time to protect a diner waitress named Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton), the other an unstoppable machine (Arnold Schwarzenegger) sent to kill her; their paths will eventually cross on a dance floor. A breathlessly efficient B-movie of choreographed momentum and comic-book-panel compositions, The Terminator showed sci-fi could be as brutal and lean as the starkest pulp; Schwarzenegger’s angular physique would never be put to more perfect use. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

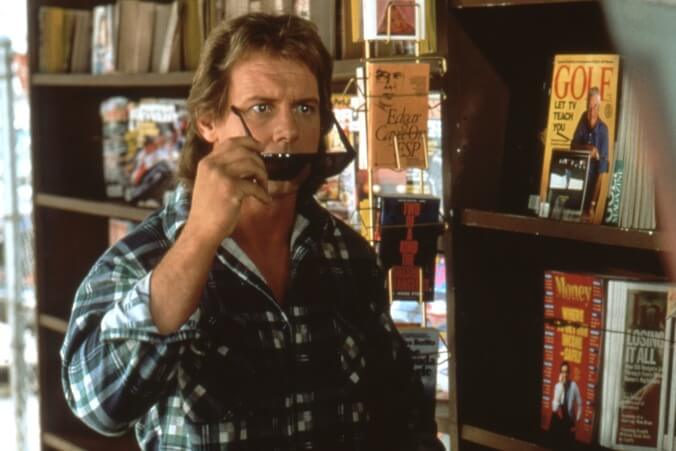

John Carpenter’s 1988 cult classic isn’t subtle about its anti-capitalist message, bluntly emblazoning it across the “OBEY” billboards that only its special sunglasses-wearing hero can see. Still, the fact that just speaks to how deftly They Live resonates with everyone’s inner conspiracist, where we’re secretly convinced that we’re at the mercy of powerful forces beyond our control. In the case of “Rowdy” Roddy Piper’s construction worker, those forces are actual aliens living among us who use subliminal advertising to keep the populace living as docile, conformist consumers. It’s a simple premise—Orwell meets AdBusters meets your freshman year of college—but Carpenter turns that anti-yuppie screed into the kind of fun, satirical romp where Piper and Keith David can just . And he gives it such lasting iconography, it’s still being referenced (and misinterpreted) 30 years later. [Sean O’Neal]

The most important technology in Inception isn’t the largely unseen dream-invading machine that drives the plot, the numerous clocks Christopher Nolan focuses on lovingly, or even that infamous top. It’s something much older and more sacred: the labyrinth, particularly of the unsolvable, Borgesian sort, which reconfigures itself at every turn and reveals ever-expanding mazes within mazes. Designing one is Ariadne’s first challenge upon joining the team—an introduction that, once the film’s game-like mechanics are established, proves increasingly fitting as each character’s psyche is revealed to be a series of logical puzzles. The competing wills of a dying scion, the careful set-up that leaves DiCaprio’s Cobb framed, the layered deceits that make Cillian Murphy’s Robert Fischer comply with the team raiding his mind: Nolan literalizes these as three-dimensional space, staging them as crumbling modernist nowheres, secret air ducts infiltrating a snowbound fortress, a train barreling through a rainy city street. How strange and beautiful that all of these serpentine mechanisms reveal at last Nolan’s most personal film: a harrowing chess match between lovers, the final resolution of which makes that still-spinning top irrelevant. Cobb finds his way out of one maze, and stops wondering if he’s in another, which is about as idealistic a resolution as any restless creative mind could dream. [Clayton Purdom]

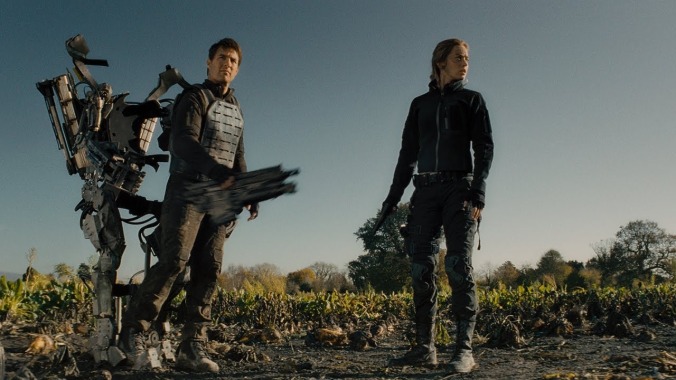

Call it Edge Of Tomorrow, or Live Die Repeat, or—to repurpose the hilarious title of its manga source material—All You Need Is Kill. Under any name, Doug Liman’s fiendishly clever almost-hit already feels like a new classic of the genre, one that can be comfortably re-watched about as many times as its main character croaks. Drafted into the real-life game of Space Invaders that he thoughtlessly propagandizes, Tom Cruise’s slimy military spokesman promptly dies on the battlefield, only to continuously re-spawn, trapped in a loop of his final hours. Like Bill Murray in , he becomes a better man (and in this case, a better soldier) through repetition, while also falling in love with the badass comrade (Emily Blunt, going full Sigourney) who forgets him after each reset. The true gallows-humor genius of Edge Of Tomorrow is how it plays with the audience’s love/hate feelings toward Cruise himself. We get to have our cake and eat it, too: basking in the aging actor’s still-formidable star power, while also taking a perverse pleasure in seeing him bite it over and over and over again for our amusement. [A.A. Dowd]

Wriggling larvae, blue-tipped orchids, fatted sows, a couple with a bond on the molecular level: Director, writer, producer, star, editor, cinematographer, soundtrack composer, and presumptive orange slice-bringer Shane Carruth takes far more interest in rendering the pieces of this vivid puzzle with stunning clarity than fitting them together for us. The audience instead processes this enigma on experiential, even spiritual terms. (Terrence Malick has been widely over-compared as of late, but if the Texan heritage and fluid long takes of elemental forces fit…) And while Carruth has rightly drawn praise for his quixotic impulse to do it all, his collaborators brought a lot to the table as well; costar Amy Seimetz sprints the entire emotional gamut, and coeditor David Lowery’s fairy dust has been sprinkled all over the final cut. But it’s Carruth who has the direct link to the primal energy source—a fuel glacial or volcanic—that powers this frugal mindblower. [Charles Bramesco]

One of the most rousing (and financially successful) blockbusters of the 1990s plunks three scientists and a couple of pesky kids in a theme park where cloned dinosaurs have been let loose in a perfect storm of hubris and greed. It’s not exactly profound stuff, though David Koepp’s script hides layers of irony and self-reflection. Director Steven Spielberg’s mastery of special effects has rarely been more seamless (or necessary) than in this blockbuster about the blockbuster era; the moral is that the wonders of technology are best handled with care, and it’s . The park’s tycoon master, a more sympathetic character than in Michael Crichton’s bestselling novel, watches on as his technical marvels of childlike wonder begin tearing his audience to shreds. Yet Jurassic Park is, above all, tremendously fun, from the John Williams score to, yes, the chomping T-Rex. It’s the first of three Spielberg movies to make our list. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

From the city that put America on wheels, then automated itself out of work, comes the future of law enforcement: a tragic hero whose resurrection and redemption are encased in Detroit steel. The cyberpunk saga of Officer Alex Murphy, Omni Consumer Products, and Delta City makes for the smartest stupid movie of the 1980s, all the big ideas rattling beneath its chassis contributing to a deafening din of glib commercials, T&A sitcoms, and nonstop gunfire. It’s a warning shot about American greed and violent cowboy justice that could only come from an outsider like Paul Verhoeven, whose near-future Motor City exposed the polluted, putrid soul of Ronald Reagan’s United States, then launched a goddamn franchise out of the toxic waste. RoboCop incriminates while it absolves: The satirical spikes and eminently quotable script—“I fuckin’ love that guy,” “Can you fly, Bobby?”, “I’d buy that for a dollar!”—can’t be separated from the extreme bloodlust. Dead or alive, you’re coming with RoboCop. [Erik Adams]

Early on in Videodrome, Max Renn (James Woods) receives a warning to stay away from the mysterious snuff porn he’s stumbled upon. “It has something that you don’t have, Max,” he’s told. “It has a philosophy. And that is what makes it dangerous.” What follows is David Cronenberg’s feverish thesis statement, not just because Renn ignores the warning, unlocking a portal to psychosexual transgression and physical transformation, but because it’s filmed and presented impassively, uneasily leaving the viewer to determine what that philosophy is and why we should fear it. Videodrome presents a “battle for the mind of North America” fought through screens, its antagonist a hungry corporation looking to control America’s eyes for corporate gain as well as some other, more eschatological end. In an era of reality-TV politics, carefully constructed and monetized digital avatars, and constant surveillance and broadcasting, it’s easy to think that we lost this battle. But Cronenberg’s concerns are less didactic, tracing instead Renn’s metamorphosis from opportunistic nihilist (“the world’s a shithole, ain’t it?”) to free-roaming agent of anarchy. Its only concern is to normalize the religion of the new flesh, its violence a capsule that helps install the philosophy deeper in the brain. This very nebulousness is what makes Videodrome still so resonant, and indeed so dangerous on its own. Like Renn, we watch on despite these warnings, the screen flickering too seductively to turn away. [Clayton Purdom]

No, it’s not as primal and gritty, as efficiently cool, as its low-budget predecessor. How could it be, with James Cameron reprogramming one of the most terrifying villains in movie history—Arnold Schwarzenegger’s literal killing machine—into a catchphrase-spouting bodyguard? With T2, fans had to settle for something different: the platonic ideal of summer blockbusters, a peerless big-budget entertainment with brains, brawn, and soul to spare. Cameron broke the bank on the set-pieces, which seamlessly blend muscular practical action with early but still-remarkable CGI, most notably in the deadly metallic-goo wizardry of Robert Patrick’s amorphous T-1000. But he also expanded upon the original’s open questions of fate and destiny, and located a strange new poignancy in a not-quite-nuclear family (mother, child, time-traveling mechanical father) attempting to stave off nuclear annihilation. By the film’s closing act of sacrifice, less guarded viewers may struggle to hold back the tears the T-800 could never cry. Cornball catharsis may be an odd substitute for relentless menace, but shouldn’t every sequel plot a new future instead of getting stuck in the franchise past? [A.A. Dowd]

Time has been kind to Starship Troopers, just as Starship Troopers has been very unkind to our time. These days, the tongue-in-cheek politics of the film—a bunch of kids from a futuristically Caucasian version of Buenos Aires enthusiastically head into a slaughterous battle against giant alien bugs who may not have intentionally instigated any conflict—veer from darkly funny to plainly chilling. Look no further than the late-movie sight of then-fresh-faced Neil Patrick Harris done up in Third Reich-style duds—a total Paul Verhoeven move that no longer feels as out-there as it did during its initial release. Of course, plenty of 1997 audiences, and even critics, took the movie at face-value (“Melrose Space” was a common crack at the movie’s overscrubbed cast of bland normies, plus Jake Busey). The dirty secret of Starship Troopers is that plenty of it does work on a surface level: if not as a feat of ensemble acting, certainly as an intensely gory and quotable Aliens riff (plus Jake Busey). The gnashing war-movie sensations fuel the satire, and vice versa. [Jesse Hassenger]

Hollywood’s love affair with Philip K. Dick began with Blade Runner, but it didn’t end there; the 35 years that separate the original from this week’s belated sequel are dotted with adaptations of the sci-fi author’s brain-bending work. Planted at the nexus of thrilling and thought-provoking, Minority Report towers over most of them. Like Blade Runner, it’s a heady detective yarn, set in a nightmarishly credible tomorrow when criminals are arrested before they commit their crimes; Tom Cruise, in dashing Mission: Impossible mode, is the cop pitted against his own ethically suspect methodology, running from the law and a possibly foregone conclusion, otherwise known as fate. The middle chapter in Steven Spielberg’s unofficial, early-2000s sci-fi trilogy, Minority Report reconfigures Dick’s source material into a breathless chase picture, allowing for some of the coolest set-pieces of the director’s career, but also for the construction of a future so technologically plausible that it’s . Even the rosy Spielbergian upshot can’t kill the suggestion that we’re seeing a troubling premonition of now: Today, as in Minority Report, what you only might do could get you arrested or worse. [A.A. Dowd]

The fact that it’s been less than a year since it hit theaters may account for this weighty sorta-thriller landing outside of the top 10: There’s a good chance that Arrival could go toe-to-toe with some of the best science fiction ever once some real time has passed. Working from a novella by Ted Chiang, Blade Runner 2049 director Denis Villeneuve retells the familiar story of an alien appearance here on earth, only with the far more plausible premise that these strange creatures would have no fucking clue how to talk to us. Bolstered by uniformly strong performances (Amy Adams and Jeremy Renner do some of their best work here), Arrival tackles a tired subject in a fresh way, emphasizing the need for communication above all else. It suggests that taking the time to be respectful of one another, and clearly convey our thoughts and feelings, might literally be the most important thing on Earth (or other planets), and that’s a message that deserves to resonate with any generation. [Alex McLevy]

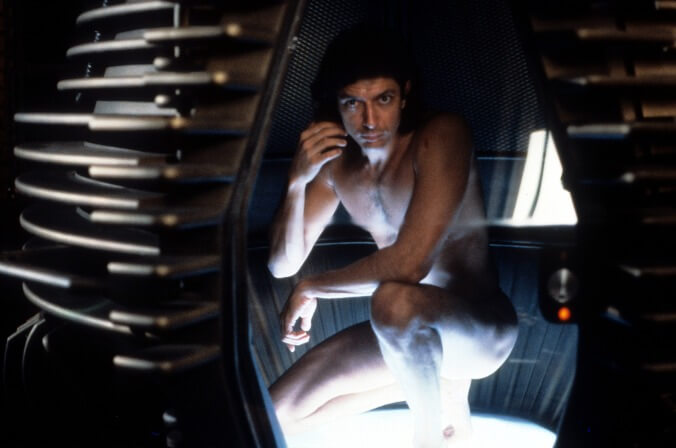

In the annals of mad science, has a god-playing genius ever regretted his own hubris more than Seth Brundle regrets his? Suffering a mishap with his homemade teleportation device, Brundle accidentally merges his DNA with that of a common housefly, and the day-by-day results aren’t pretty. Of course, there’s much more than a fear of unchecked ambition to be gleaned from David Cronenberg’s stomach-churning, heartbreaking remake of a ’50s schlock staple. Whether viewed as an early AIDS allegory, a cautionary tale about drug abuse, or some combination of both, The Fly creates goopy, grand entertainment from one of life’s worst ordeals: helplessly watching as a loved one wastes away. Geena Davis, in a star-is-born performance, makes that horror palpable, while Jeff Goldblum, emoting fiercely under pounds of amazing prosthetics, plugs the audience into this crucible of mind-and-body deterioration, infecting us with his fear and disgust and scientific wonder. He’s Frankenstein and the monster rolled into one: a BrundleFly of mankind’s defiance of limits and the sometimes-gruesome consequences of the same. [A.A. Dowd]

“Species meets Morvern Callar” may sound like an odd mix, but writer-director Jonathan Glazer’s adaptation of a Michel Faber novel makes that combo work. Scarlett Johansson gives one of the best performances of her career as a creature who seduces and consumes lonely men, in docu-realistic footage shot on the sly in nondescript Scottish cities and villages. Every now and then, Glazer strands the audience in the heroine’s spooky extra-dimensional lair, which looks like a pool of inky black, dotted with abstract gray blobs. Under The Skin is an arty spin on a cheesy B-movie premise, allowing audiences to experience both the mundanity of our world and the forbidding darkness of an alien realm through non-human eyes. It’s as mesmerizing as it is disorienting. [Noel Murray]

Spike Jonze’s Academy Award-winning foray into full-scale sci-fi is a contemplation of timeless emotions and modern technology, anchored by two of our greatest living movie stars—one of whom is also today’s versatile genre-film personality (see above). And Scarlett Johansson doesn’t even appear onscreen in Her: She’s the ghost in Joaquin Phoenix’s machines, the increasingly sentient OS providing companionship to a divorcé who spends his days conjuring feelings for total strangers. It’s dystopian in premise yet utopian in outlook, its simultaneous awakenings set against the backdrops of a globalized L.A., a wordless Arcade Fire record, and cinematography that starts out fixated on Phoenix but gradually expands its scope as he starts seeing beyond himself. In some ways, it’s the anti-Blade Runner, the congestion and techno-paranoia of Ridley Scott’s classic flipped to find a protagonist in retro-futurist fashions who’s never in doubt of his humanity, living in harmony with a female AI discovering (and transcending) her own. [Erik Adams]

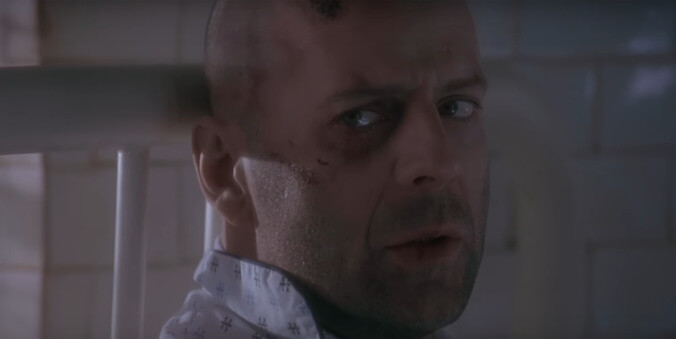

Terry Gilliam’s era-traversing thriller has all the elements of a science-fiction slam dunk: time travel, a dystopian future, a killer virus, Bruce Willis. As post-apocalyptic convict James Cole, Willis travels from a very Gilliam-esque steampunk bunker in the near future to try and figure out the origin of the disease that nearly destroyed humanity. His trip goes sideways, naturally, as he meets a skeptical scientist (Madeleine Stowe) who later becomes his kidnappee, then his Stockholm syndrome ally, and a mental patient (Brad Pitt, in his first Oscar-nominated role) who leads the story in new directions. But it’s 12 Monkeys’ twisty narrative—inspired by Chris Marker’s short-form stunner “La Jetee”—that makes 12 Monkeys a classic. Gilliam’s version was written, perhaps not coincidentally, by Janet and David Peoples, the latter of whom penned the masterpiece that inspired this very list. [Josh Modell]

Steven Spielberg’s thoughtful and profoundly sad fairytale about a childlike android (Haley Joel Osment) who wants to become a real boy is about as dark as a special effects fantasy can get without betraying its core principle of wonder. Programmed to yearn for his adopted human mother’s love, little David travels through the garish neon metropolises, drowned downtowns, and robot demolition derbies of the future in search of Pinocchio’s Blue Fairy, accompanied by a fugitive sex-borg (a pitch-perfect Jude Law) and a super-intelligent teddy bear. Stanley Kubrick originally developed the project, but A.I. is a movie that only Spielberg could create. (It’s also one of only two scripts that he’s written for himself to direct; the other is .) The most delicate of sci-fi masterpieces, it concerns itself with the world we leave behind, discovering humanity in our last traces; the deeply moving ending is its own Voight-Kampff test. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

George Miller’s feature-length chase scene (give or take a couple of rest stops) envisions the fluid, mythical post-apocalyptic setting of the anthology-like Mad Max series as a wasteland ruled by humanity’s earliest wrongs. Reimagined as a traumatized veteran, Max Rockatansky (Tom Hardy, taking over the role previously played by Mel Gibson) becomes the reluctant ally of the one-armed truck pilot Furiosa (Charlize Theron) as she leads a harem of young beauties to a half-remembered society of women, pursued by the patriarchal death cult of Immortan Joe and his War Boys. The metal-twisting, pyrotechnic vehicular carnage is consistently exhilarating—“pure” action at its most gloriously over-the-top. But the thrill of escape takes on a different meaning here; while science fiction traditionally looks to the future, Fury Road is all about the eternal past, racing to catch up in the rear-view mirror. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

Opinions of Shane Carruth’s no-budget debut (which unexpectedly won the dramatic prize at Sundance) tend to be sharply divided, depending upon whether one finds its recursive narrative challenging or simply impenetrable. There’s certainly no denying that it puts the “science” in science fiction. Primer’s dual protagonists, Aaron (Carruth) and Abe (David Sullivan), are engineers, and they talk like engineers, without bothering to explain themselves for an audience of laymen; the film’s dialogue is a torrent of jargon, meant to be experienced as a disorienting whole rather than processed line by line. Equally cryptic are the characters’ motivations, about which Carruth provides only hints. All that can be stated with confidence is that Aaron and Abe, while working on a side project in Aaron’s garage, accidentally invent a limited form of time travel into the past, and that a combination of ego and paranoia leads to multiple versions of both men existing simultaneously. Fans have created elaborate, brain-numbing diagrams that attempt to work out exactly what happens, but the film’s genius lies in its cerebral embrace of uncertainty, along with Carruth’s precise visual sense and his almost quixotic faith in the viewer to keep up. [Mike D’Angelo]

Let’s talk about the opening stretch of WALL-E, in which the exacting geniuses at Pixar introduce their bleak premise: In the far-flung (but perhaps not quite distant) future, a garbage-saturated Earth is no longer inhabited by humans—just a single trash-collecting robot chipping away at endless, impossible clean-up duty with a side of slapstick misadventures. In mere minutes, the movie establishes a chilling vision of our planet’s future, and does so in silent-comedy language that barely-verbal children might still understand. But let’s also talk about the rest of WALL-E, the part of the movie sometimes unfairly maligned as a comedown from that magnificent opening. Once WALL-E winds up on the Axiom, a massive spaceship on an endless cruise, the movie deepens its critique of consumerism run amok via devolved, blobbed-out humans no longer programmed to think or even walk for themselves. At the same time, it finds gentle poetry in a romance of sorts between two machines who may be cute but are never cheaply humanoid. Pixar may attempt to solve humanity’s problems with a series of elaborate action sequences, but when this involves the best robot chases this side of a Terminator movie, it’s hard to complain. The opening creates a world, but the whole movie tells a story. [Jesse Hassenger]

Perhaps more than any other year in recent memory, 2017 has inspired constant talk of the most pertinent or prescient dystopian visions. Alfonso Cuarón’s Children Of Men might be the film to beat among those contenders, tapping into current debates on refugees, immigration, and even reproductive rights. But the movie is more than the sum of its political parts. Adapted from a novel by P.D. James, it presents a harsh vision of the future, when human civilization is basically in its death throes—and that’s just in the first few minutes. From there, Clive Owen’s Theo must find a way to shepherd the first pregnant woman in years across a war-torn England, evading factions who would use her unborn child to further their own agendas. Owen, Julianne Moore, and Michael Caine all deliver gut-wrenching performances, and the use of elaborate, unbroken long takes develops a cinematic language as powerful as its emotional one. [Danette Chavez]

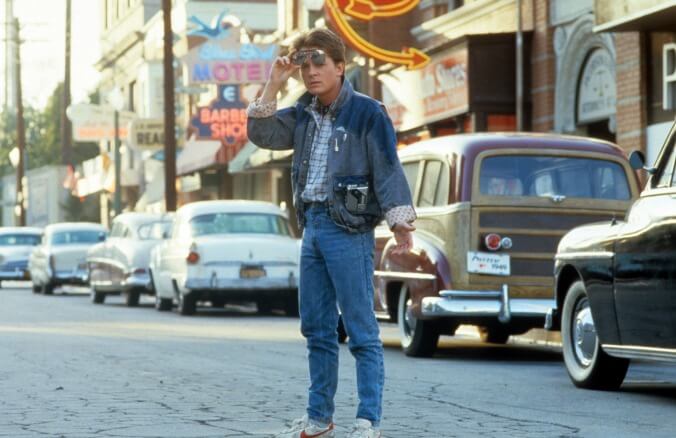

The science is shaky—a plutonium-fueled DeLorean defies quantum physics to travel back in time, paying blithe lip service to the many paradoxes it creates—and its fantastical premise is really just the contrivance for a sweet culture-clash comedy about an 1980s teen who meets (and tries not to sleep with) his 1950s parents. Yet for all its long-debated “hard sci-fi” flaws, Robert Zemeckis’ Back To The Future remains our most beloved modern time-travel story, as responsible as Doc Brown’s heroes Jules Verne and H.G. Wells for popularizing the basic concepts and causalities of messing around with our destinies. Meanwhile, its sequel continues to be the most widely referenced vision of our (now passed) future, as the annual deluge of hoverboard articles attests. All told, Back To The Future’s massive, crossover success performed the equally improbable feat of making science fiction broadly appealing, every bit as cool to the kids as Huey Lewis. [Sean O’Neal]

If there’s a glimmer of hope that James Cameron won’t be wasting his talent with four more rounds of , it lies in the knowledge that this maestro of blockbusters is also, generally speaking, a master of sequels. The director knew how to expand his stone-cold Terminator into an awesome multiplex epic. Before that, he achieved the even more daunting feat of pulling a new sci-fi classic out of the shadow of an old one. Rather than try to replicate the glacial deep-space dread of a Ridley Scott movie arguably even better than Blade Runner, Aliens stomps on the gas, stranding an unfrozen Ripley (tough-as-nails Sigourney Weaver) on an outpost crawling with acid-bleeding creatures, alongside a platoon of over-armed but severely underprepared space marines. Few action or war movies released in the decades since can match Aliens for sheer adrenaline-junkie intensity, but there’s something affecting about its emotional arc, too—about the way Cameron turns the déjà vu storytelling logic of sequels into warped immersion therapy, allowing Ripley to overcome the trauma of Alien (and the loss of her daughter) by rushing back into the monster-blasting fray. It’s not a redo. It’s a rebirth, bursting bloody and triumphant from the cold body of a perfect genre specimen. [A.A. Dowd]

Terry Gilliam’s dystopian vision, which he considered titling 1984½, so confounded Universal Pictures that it nearly wound up being shelved; only after the Los Angeles Film Critics Association named Brazil the year’s best film—based on secret, unauthorized screenings—did the studio finally relent and release it. Despite clear Orwellian parallels, they’d somehow expected something more conventionally heroic from this tale of a Walter Mitty-ish bureaucrat (Jonathan Pryce) who fantasizes about rebelling against the totalitarian system he helps to administer. Gilliam instead delivered a merrily bleak portrait of amoral dysfunction, mixing absurdist comedy with nightmarish imagery in truly unsettling ways. Nor does Brazil offer an escape by way of pure spectacle—while the conception of its alternate world is visually astonishing (especially for its relatively low budget), Gilliam shrewdly challenges sci-fi orthodoxy by rooting extrapolations of the future in antiquated aspects of the past. Even the title, which refers to a popular romantic song written in 1939, seems designed to foster cognitive dissonance. The result is a movie so recklessly singular that it came dangerously close to never being seen in its intended form. [Mike D’Angelo]

A pastiche of influences and references (Hong Kong action, Alice In Wonderland, anime, The Wizard Of Oz, body horror, etc., etc.) wrapped in greenish tints, undergrad philosophy and memorable special effects, the Wachowskis’ breakthrough became a cultural touchstone and a massive, influential box-office hit by striking an unlikely balance between style and substance. It seems to have something for everyone. The premise—reality as a simulation created by sinister machines—is versatile enough to fit any reading across the political spectrum, but the subtexts of identity and self-discovery are deeply personal. Every ambitious sci-fi film made since the 1980s is, in some elementary way, about the genre itself. The Matrix takes its possibilities—as gee-whiz effects spectacle, allegory, secular mind-blower, escapist fantasy—and fashions them into a worldview. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

At its best, science fiction is a mirror. It shows us not just other planets, other eras, and other species, but also ourselves, refracted through the smoke screen of impossible conceits and creative prognostication. Directed by impish French daydreamer Michel Gondry, from a brilliant script by the mad genius screenwriter Charlie Kaufman, Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind fulfills the full potential of the genre as a window into human experience, all while functioning as maybe the quintessentially funny-poignant love story of 21st-century cinema. Just the premise alone might have triggered all the synapses in Philip K. Dick’s noggin. On the receiving end of an especially brutal breakup, introverted sadsack Joel (a perfectly cast-against-type Jim Carrey) pays a team of cerebral janitors to wipe away all mental traces of the dead relationship. But as memories disappear into the void, Joel has second thoughts about forgetting it all, and begins scrambling through his own subconscious, trying to hide extroverted ex Clementine (Kate Winslet, in what essentially amounts to a plum dual role) in the deepest folds and recesses of his brain. Gondry and Kaufman turn the Lacuna, Inc. procedure into a fantastic voyage of collapsing landscapes and reality-bending hallucinations; in its own in-camera, lo-fi way, Eternal Sunshine is as much a special effects showcase as any blockbuster on this list. What makes it our undisputed top choice is the way the film uses a high-concept hook for the ages to make a profound point about human nature, about our stupid, reckless, romantic willingness to endure life’s lows in pursuit of its highs. Working its way to the of the new millennium, Eternal Sunshine suggests that time, space, and oblivion are no more mysterious than our own complicated, sometimes contradictory desires. That’s a whole universe to explore. [A.A. Dowd]

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.