The 35 greatest horror games of all time

A list of games as varied in the ways they try to terrify players as there are ways to be terrified

What scares you? It’s a question you know the answer to innately and immediately, as individualized as your fingerprint. Accordingly, horror games have tried everything in the book in order to scare players: disempowerment, alienation, animatronic jump-scares, eroticism, flagrant shattering of the fourth wall, and so on. The history of horror games could serve as an alternate history of games themselves, one where the medium doesn’t get cleaner and more empowering with each passing year but increasingly disorienting, difficult, and abstract. They’re a home for experimentation, where conventions are upended and taboos are shattered. They’re also fun as hell—a realm where the violence of other games is newly purposeful, and game designers are free to exercise their most out-there tendencies. Even a simple jump-scare, often eye-rolling in movies, gains a strange new power when you’re the one inching forward through the basement.

The A.V. Club’s trip through the history of horror games found endless tensions to unpack: playability versus difficulty, spooky-fun versus truly terrifying, historical importance versus modern appeal. Mostly, though, we agreed on games that come alive with the possibilities of horror, whether it’s splattery gore, psychedelic architectural spaces, or truly gonzo game mechanics. The result is a list of games as varied in the ways they try to terrify players as there are ways to be terrified.

To put it together, we asked a group of A.V. Club staffers and contributors to submit ranked ballots and tallied up the votes. Any game—including remakes and “teasers”—was up for grabs.

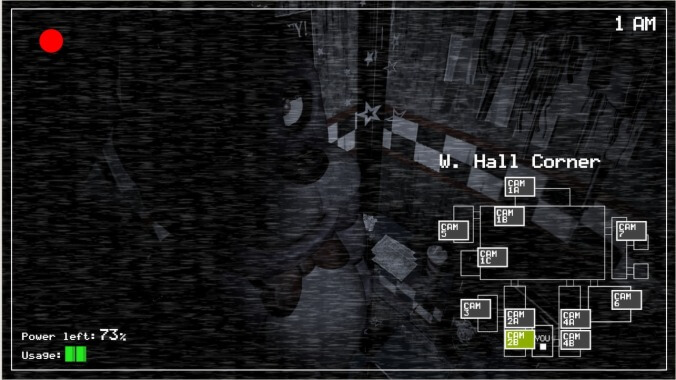

There’s a great tradition in horror cinema of the low-budget, unexpected success immediately generating a raft of sequels, spin-offs, and rip-offs, whether it’s the post-Halloween wave of holiday-themed slasher flicks or the immediately annualized Saw franchise. After the astonishing viral success of Five Nights At Freddy’s, creator Scott Hawthorne cranked out three sequels in less than a year, all essentially reiterating the same titanium-strength formula: Chuck E. Cheese-style animatronics stalking the restaurant halls at night, attempting to murder the night security guard. Eventually the games would develop a broader mythos, but the economical and brutally effective first installment is the best—a shrine to the jump-scare navigated via a spectral, faulty surveillance system. It’s a viewing framework that proved perfectly suited for YouTube, where the tension creeps through the stream and the game’s flash-cut scares turned the platform into a vast, internet-wide movie theater. [Clayton Purdom]

Beat-’em-ups aren’t usually cited for their white-knuckle scariness, unless your list of personal phobias includes street brawling and blowing all your laundry money. But Splatterhouse gave that button-mashing genre a fresh coat of blood-red paint, replacing the usual interchangeable goons with grotesque ghouls, to be clobbered, chopped, and chainsawed into pulp. Granting control over a college student transformed into a hulking monster hunter by his magical, conspicuously Vorheesian hockey mask, the series broke new ground for content warnings (“The horrifying theme of this game may be inappropriate for young children… and cowards,” went one disclaimer), while offering level design gross enough to satiate any Fangoria subscriber. Splatterhouse 3, which got name-checked at the congressional hearings on video-game violence, brought a three-dimensional range of motion to the franchise’s primitive Evil Dead combat. But the cleverest innovation was a countdown clock: Take too long clearing a path through the titular mansion and your cowering loved ones are goners. Good luck wringing that kind of suspense out of Double Dragon. [A.A. Dowd]

It was strange enough seeing Nintendo’s name, synonymous with brightly nonthreatening all-ages entertainment, on a survival horror game. Stranger still was the direction the company dragged the genre: Eternal Darkness broke with the highly popular Resident Evil model to tell an ambitious, layered, eon-spanning Gothic narrative. Where this GameCube cult classic truly distinguished itself, though, was in its ingenious and literally patented “Sanity Effects”: Spotting a monster takes a quantifiable toll on your mental health, and as that particular bar drops, the game begins seriously altering your perception—with aural and visual hallucinations, with apparent glitches in the level design, with simulated technical hiccups and storytelling fake-outs. Whether Eternal Darkness really qualifies as “psychological horror” is debatable—you still spend most of your time slashing zombies. But anyone who felt even a tinge of panic as the game disconnected their controller or calmly insisted it was wiping their memory card could relate to its repeated mantra of terrified reassurance: “This isn’t really happening.” [A.A. Dowd]

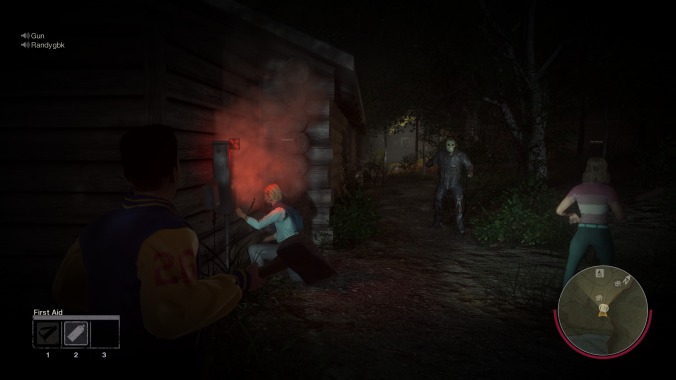

From its cartoonishly violent kills to its lovingly recreated ’80s-summer-camp backdrops to the persistent “ki ki ki, ma ma ma” on the soundtrack, last year’s asymmetrical multiplayer adaptation of the popular slasher series is the closest you can get to actually living through a Friday The 13th movie—assuming, of course, that you do live. The game casts a handful of players as camp counselors evading Jason Voorhees, with another player assuming command of the hulking, supernatural mama’s boy. Counselors can set traps or pick up weapons, but winning usually comes down to hiding until the clock runs out or figuring out how to escape. Meanwhile, Jason has all of the unfair powers that he has in the movies, including teleporting anywhere on the map and silently stalking prey without anyone noticing the huge guy in tattered clothes and a hockey mask stomping through the woods. That there’s a real player, instead of AI, controlling the killer’s movements actually makes them a little scarier. Mostly, though, this buggy, imperfect party game captures the communal fun of a bad-good slasher, allowing fans to make the same dumb decisions they usually yell at people on screen for making. [Sam Barsanti]

So integral is the original Doom to the evolution of the first-person shooter that people often overlook how effectively it takes a chainsaw to your nerves. The premise is an Aliens gloss, dropping players into the boots and helmet of a lone space marine stranded on a Mars outpost overrun by Hellspawn. Periodic breaks in the hectic, run-and-gun carnage create pockets of anxiety, as you round blind corners or sprint into darkness, waiting to be ambushed by the next horde; sometimes you hear the threat before you see it, an offscreen snort or growl portending your, well, doom. The game’s locked POV became a lynchpin of its controversy—kids were experiencing the violence firsthand through their own eyes, like little Michael Myers in the opening minutes of Halloween. But that first-person vantage also worked like gangbusters as a tool for terror, erasing the safe distance between player and beleaguered avatar. Doom may have largely birthed the modern shooter, but no one should forget the influence its nightmarish tunnel vision had on horror gaming, too—from the immersive shocks of fellow PC milestone Half-Life to the sadistic tricks of perspective pulled by our top choice below. [A.A. Dowd]

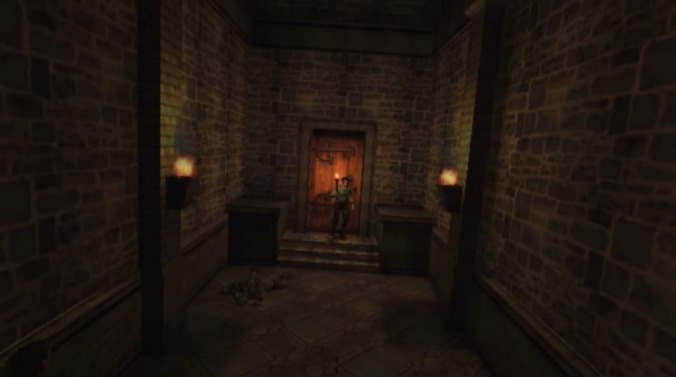

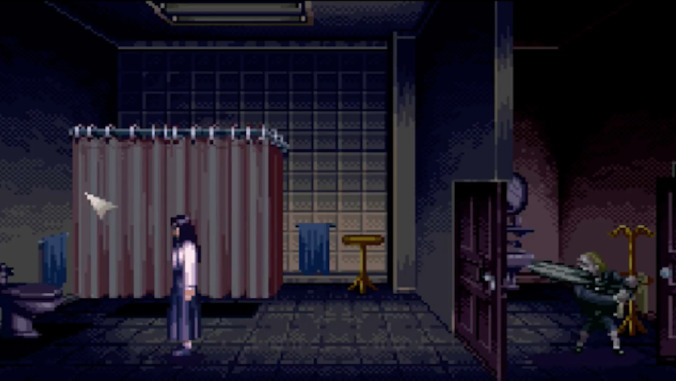

Thirteen years before Amnesia: The Dark Descent made total disempowerment gaming’s horror-mode du jour, Japan’s Human Entertainment made the case for the terror of helplessness with Clock Tower. This point-and-click adventure weaponizes your curiosity against you, turning every innocent click on a shower curtain or piano into a tense test of fate that may very well result in the surprise appearance of the Scissorman, a murderous little fella who gleefully pursues our hero, Jennifer, with cartoonish clippers. The only thing saving her are her wits and scrambling feet—and even those can fail in her most panicked moments. With obtuse puzzles, a mansion that’s a nightmare just to get around, and a main character who makes Resident Evil’s barely mobile heroes look like parkour masters, there’s a great deal of Clock Tower that has aged miserably. But it remains a subversive triumph, its giallo-inspired mystery and threatening atmosphere impossibly wrenching so much dread out of a humble 16-bit console. [Matt Gerardi]

Tecmo’s Fatal Frame series is as long-running as any of its survival horror kin, but has never quite garnered the same attention as a Silent Hill or Resident Evil. Fatal Frame III: The Tormented is the high point—building on its nearly-as-good predecessor to create an unapologetic, polished work of Japanese folk horror. It marks a final burst of creative ambition before the series was shackled to two consecutive Wii systems. With its trio of lead characters, entwining timelines, and focus on a supernatural force gradually invading a domestic space, it has the scope and eerie force of something like Kōji Shiraishi’s found-footage classic Noroi: The Curse (2005). If taking magical pictures of excruciatingly slow ghosts while solving obtuse puzzles sounds a little “not for everyone,” well, these games are classics because they refused to tone it down. [Astrid Budgor]

At first glance, there’s not much more to recommend Ivan Zanotti’s indie horror classic (later expanded and re-released on Steam in 2016) than its creepy atmosphere, nastily effective jump-scares, and ever-present fog. But then the program starts pushing aggressively at the boundaries of the fourth wall, tossing up fake crash bugs, filling a folder on your desktop with eerie little messages from its spectral antagonist, and doing everything in its power to present itself, not simply as a game, but as a sort of otherworldly virus infecting your system. For most horror games, the quit button is the ultimate escape from threats, but Imscared turns your computer itself into the house that’s being haunted, leaving you with nowhere to run or hide from White Face’s uncanny stare. [William Hughes]

System Shock and its sequel (see below) work in part as large-scale interactions with a terrifying antagonist named Shodan, a ship-controlling, world-dominating AI. Released more than a decade later, Cyberqueen is a short, beguiling piece of interactive fiction by Porpentine about what it would be like to be in her clutches. What it would be like to be deformed, transformed, made something entirely other than human at the hands of a detached digital divinity. It is, unique for video games, a bit other than just straight horror. It’s borderline erotic horror, depending on your tastes. Cyberqueen builds itself on the assumption that losing your identity at the hands of an omnipotent machine domme is terrifying. But also, probably, kind of hot. [Julie Muncy]

Condemned deserves its place in the horror-game hall of fame if only for one level, set inside an abandoned department store full of discarded mannequins and—in a truly vicious gimmick—killer maniacs dressed like mannequins. Video game enemies tend to look the same, and the decorations in a video game level tend to look the same, so Condemned plays off of both of those “limitations” by having the enemies look (and act) just like the set dressing, right up until the moment you turn your back and they run after you. The rest of the game is equally seedy, following a depraved FBI investigation into the decrepit buildings of a city whose inhabitants seem to be going mad. They’re all just as eager to beat you to death with a pipe as those mannequins were, too. [Sam Barsanti]

The horror of recursion is a rare and special kind, and one Echo relentlessly pursues. Obsessed by the uncanny qualities of repetition, mirroring, and infinite loops, its planet-sized palace is Versailles trapped in a crystal prism, glittering, eternal, ingrown. This setting offers the player a palpable sense of creeping dread, but it is the rhythmical, panicked quality of the game’s tactical stealth that delivers the fear. In Echo you charge on through cycles of darkness and blinding light, trying to twist the game’s increasingly ornate rules to your benefit. Evasion at any cost is balanced by restriction, as any action you perform is inherited by the doppelgängers that pursue you. The result is a malformed hybrid of puzzle, stealth, and horror, cast in the cold light of two mirrors turned to face one another. [Gareth Damian Martin]

As humans, we reserve our deepest, darkest fears not for monsters, not for murderers, but for sickness: The creeping corruption that lurks within. All three of Pathologic’s playable characters are healers, of a sort, but none of them is fully equipped to handle the rot lurking at the heart of its backwater Russian village. Poorly translated, slow-moving, and as hostile as any game ever released, Ice-Pick Lodge’s unapproachable masterpiece wants to make playing it feel as painful as living through its infected nightmare world would be, emphasizing the horror of surviving in a world of survival horror. Characters lie to you, healing items drain your other stats, and someone, somewhere, is always on the verge of being the Sand Plague’s next victim. Keep up with the tide of death, and you’ll find yourself delving into the mystical feud that’s ripping these people apart. It’s more likely, though, that you’ll make the merest misstep, and send yourself (and the village) on a spiral down into infection, madness, and inevitable death. [William Hughes]

You cannot stop the dead in Siren, an otherworldly, bitterly hard PlayStation 2 game from original Silent Hill director Keiichirō Toyama. If you’re playing as a character with a weapon—from a Clue-like cast of children, professors, and TV stars, whose faces look like photos projected onto paper plates—you can momentarily silence the giggling voices of your pursuers. But they will rise again to hunt you through dim levels designed with such malice that you sometimes have to laugh, too. You can tune into enemies’ vision, finding them like over-the-air stations between walls of wormy static, and use their patrols to build your mental map of Hanuda village. When they spot you, their sight overrides your own with a red flash, and you see your own still figure approaching within a lurching frame. In a game of overlapping viewpoints and narratives, this is the best trick: the horror of seeing yourself through unfriendly eyes. [Chris Breault]

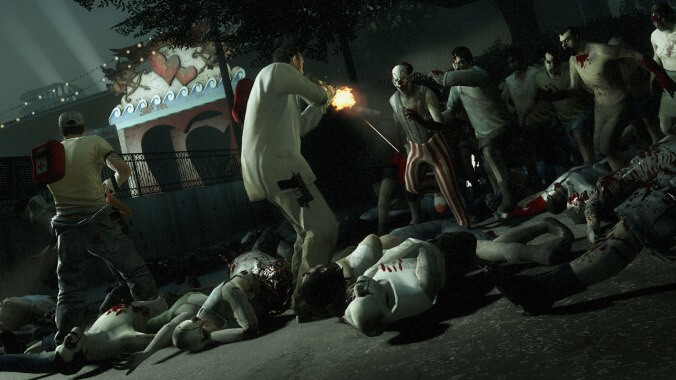

Left 4 Dead 2 unwinds the sense of isolation and disempowerment central to so many horror games: You’re playing online with a couple of friends, slashing and shooting and dousing zombies with gasoline. But as the difficulty ramps up, the “AI director” that determines when and how the hordes of zombies attack you becomes devilishly effective. All that giggly wisecracking disappears pretty quickly when you’ve got 10 rounds left in your gun and you’re staring down a couple dozen zombies, one of which is vomiting poison on the floor, and a real-life friend is screaming at you for help over a headset. There are quiet survival games, where you have to conserve whatever resources you have, but Left 4 Dead 2 is a loud survival game, where you just have to keep fighting, even as your resources dwindle to nothing, and where a team of cooperating players only raises the stakes. [Sam Barsanti]

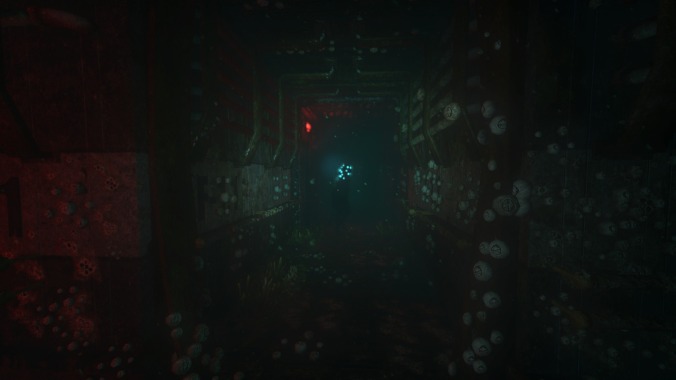

The underrated A Machine For Pigs might share the Amnesia name, but Soma was the game given the unenviable task of actually furthering . Five years of imitation had already driven Frictional’s tricks into the ground, so much so that this sci-fi nightmare’s similar monster encounters felt staid and unnecessary . But with Soma, Frictional aimed for terror of a different sort, the kind that leaves your mind racing and your stomach queasy. It’s not covering wholly original ground—delving into the well-trod territory of life, death, and digitized consciousnesses—but it does so with tact and bold, confrontational scenes that don’t suggest existential questions so much as they strap you down and force your psyche to wrestle with them. [Matt Gerardi]

Capcom’s Haunting Ground pulls from the psychosexual perversions of giallo director Dario Argento as well as older traditions of Gothic literature to create something uniquely bizarre—and, maybe, the last great classical survival horror game. Heroine Fiona is accompanied by Hewie, a White Shepherd whose mood and obedience is up to the player to manage; without Hewie by her side, Fiona is virtually defenseless against a cavalcade of villains who all want her body for their own purposes. The game’s setting is the apex of surreal, illogical survival-horror environmental design: a castle whose absurd interiors, piling up with no regard for coherence or verisimilitude, creates madness. All this madness falls on Fiona; the game’s “panic mode” sends her into a blind, uncontrollable frenzy if she becomes terrified. The entire game shapes itself around fear, in a way that is difficult to play and harder to shake. [Astrid Budgor]

Back at the turn of the millennium, when anything seemed possible, horror maestro Shinji Mikami took Suda51 under his wing. Protected by the venerable designer from commissioners Capcom, Mikami forced Suda, a serial delegator who has produced more games than he has ever directed, to write and design Killer7 alone. The result is as ambitious as it is demented, geopolitical philosophy cut through with Lynchian psychology, draped in a screen space gradient shader to die for. It cackles at you as you boot it up, the menus a jangling dance of disembodied letters. Like those letters, Killer7 refuses to cohere or collapse, but instead just rattles along, a neon ghost train, garish and extravagant. Suda readily admits he could never make anything like it again, and sometimes it’s hard to imagine anyone ever will. [Gareth Damian Martin]

In other horror games you may play a painter, a photojournalist, a sensitive person in psychological distress. In F.E.A.R. you are the Point Man, a paranormal government operative who charges in slow motion past thudding bullets and screens of gun smoke to blow soldiers in half with his VK-12 shotgun. When a Delta Force ally bellows “I live for this shit” from the chopper, he speaks for the meathead within us all. Five seconds later, he is dead.For F.E.A.R., the most beautiful flowering of mid-2000s bro action, horror is just a second way to make the player’s heart race. Solely focused on surface effects—showers of sparks, “screamer” images, ecstatic swells on the soundtrack—its sheer playability precludes the suffocating dread of other genre greats. The Point Man gets ambushed by clever AI, jump-scared by hallucinations, and startled by invisible foes; one cannot believe he is ever A.F.R.A.I.D. [Chris Breault]

Among other questions raised by Anatomy is this corker: What happens when a ghost discovers the true evil is the house it’s haunting? Designed by one-woman horror-game powerhouse Kitty Horrorshow, Anatomy tasks the player with creeping through an empty, pitch-black suburban home, finding eerie audio tapes that equate the house with a human body. The game keeps kicking you out, forcing restarts, as the tape quality degrades and the software comes untethered, revealing the house’s true nature. Horrorshow’s writing is unusually rich, pulsing with dread like a blood-engorged insect, and the audio quality is superlative, finding the beauty in data errors and digital shrieks. The result is equal parts The Disintegration Loops and Videodrome, Doom and Gone Home, an altgame classic and a ghost story for the ages. [Clayton Purdom]

Disadvantage is the key (unicorn-, sun-, or otherwise-shaped) to survival horror. Setting aside its temporary, mid-entries turn toward fast-paced action, the Resident Evil franchise has always scored scares by putting the player’s exquisitely bitable back against the wall. You rarely have enough ammo—and even when you do, the deliberately awkward controls make combat difficult. You can’t carry much on your person, which necessitates backtracking through zombie-infested territory. And save rooms are spaced far enough apart that the threat of fictional death becomes a threat of very real progress lost. Resident Evil 2 didn’t “fix” any of the original’s bugs, which were really features in disguise. Instead, it simply refined the hoard-and-evade formula, sending players creeping through the fixed, exaggerated camera angles of a new pre-rendered, postapocalyptic environment, including a police station hilariously designed around baroque puzzles. The upcoming remake will update the graphics and campy voice work, but here’s hoping it keeps intact the core fear factor: a very reasonable concern that you won’t survive the horror lurking behind every closed door. [A.A. Dowd]

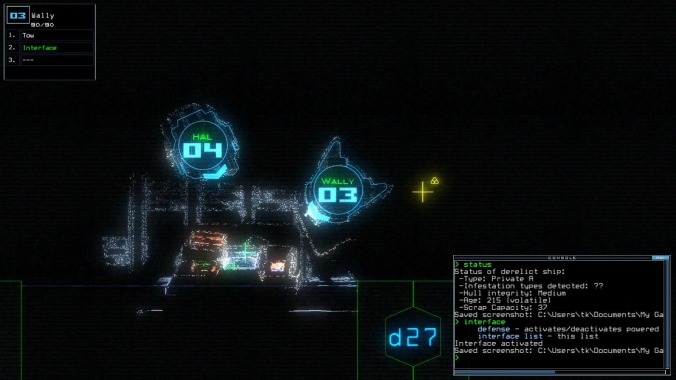

Minimalism feeds into horror. The less information you have, the more space exists for your imagination to fill in the gaps. And nothing is as creative as a scared imagination. Duskers takes minimalism to an extreme, limiting both your knowledge and your inputs. As a pilot of a wandering spaceship, you send drones in to rummage around derelicts for supplies. Your only interface is a command line, with a unique system of commands that you have to tap in by hand in order to get anything done. And, of course, those ships are full of the same horrors that have rendered half the galaxy empty. How good are you at typing precise inputs while running from unseen terrors? Probably not good enough. [Julie Muncy]

“L-l-look at you, hacker…a pathetic creature of meat and bone, panting and sweating as you run through my corridors…” That opening purr, dripping with seductive, hateful omniscience, is the sound of one of gaming’s most terrifying villains coming into her own at last. Irrational Games and Looking Glass Studio’s ambitious shooter/RPG hybrid System Shock 2 offers a little something for everyone when it comes to tapping into the primal fears—spiders, body horror, those goddamn psychic monkeys—but at the core of it all are the glories of the malevolent AI SHODAN. Voiced to digital perfection by Terri Brosius, The God Of Citadel Station never lets you forget that she is always watching, hovering over your shoulder as you gun down her wayward “children”, whispering in your ear (even when you think she isn’t), and creating the inescapable sense that she’s digging her way ever deeper into your body, and your brain. [William Hughes]

Don’t let Yume Nikki’s familiar, retro-RPG look fool you: Soon enough you’re wandering despondently through its candy-colored world, pieces of narrative swirling around each other like the details of a nightmare that refuses to end. You recall images—morose teens, malevolent spirits, raving monkeys—but they all only mount to a climactic suicide, and a gutting credits sequence. For years after its release, players pored over the game, parsing it for clues about its meaning, its creator, their fate. Even the release of a lackluster remake earlier this year hasn’t deadened the surreal allure of the game. Alongside a wave of like-minded early-millennium Japanese horror films like Ju-On and Pulse, it proposes that the very technology containing it is haunted, perhaps cursed. It turns a bleak cognitive space into an explorable two-dimensional one, forcing you to wander, to wonder—and, eventually, to escape. [Clayton Purdom]

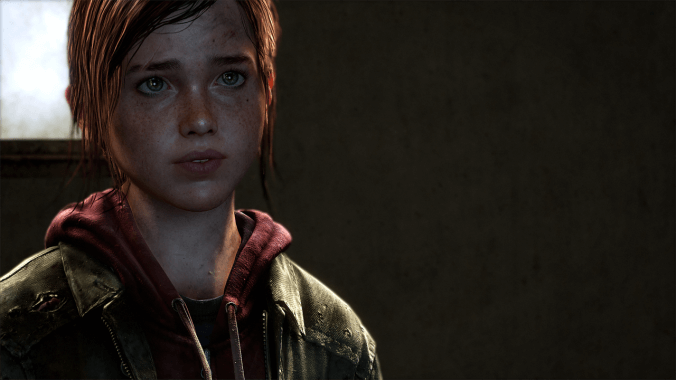

Zombies are so done to death at this point that even the George A. Romero-indebted Resident Evil series has shuffled on from them. They were moribund five years ago, too, but that didn’t stop Naughty Dog, of Uncharted fame, from yanking the genre out of its grave with an instantly beloved postapocalyptic epic. Beautifully written, performed, and designed, The Last Of Us builds its bleak narrative around the relationship between a trauma-hardened smuggler and the teenager he agrees to escort across an America crawling with both bile-spewing mutants and murderous human scavengers. The character development isn’t window dressing; it lends real dramatic stakes to the game’s intense stealth action, and propels the story forward, through time and across time zones, to a final crucible (and choice) for these desperately bonded survivors. Most zombie games give you entrails. Few games of any genre are as gutting as The Last Of Us. [A.A. Dowd]

“This town’s finished,” some bloodthirsty villager croaks after you slice him down early in Bloodborne, and, buddy, he’s not kidding. The city of Yharnam is one of gaming’s great metropolises, a Gothic labyrinth of cobblestone streets and wailing maniacs, but you arrive long after its fall, when the city’s clergy and onetime leaders have summoned great insectoid monstrosities to bear. The few sane villagers left cower behind their doors while you disembowel and are disemboweled by howling werewolves and engorged hogs and a ghostly, mutant vicar. Hidetaka Miyazaki famously reinvented the role-playing game—and recalibrated the universe’s expectations for video game difficulty—with Demon’s Souls and Dark Souls, but Bloodborne’s shift to full-on horror clarified and refined his vision. There’s no shield to hide behind in Yharnam. You walk in surgical gowns and clerical robes muttering prayers to a god that will be scientifically disproven by whatever shrieking beast comes slashing out of the darkness next. [Clayton Purdom]

Rereleased this year in an illustrated version, Michael Gentry’s Anchorhead is an interactive fiction game that takes a perspective rarely explored in the near-century of post-H.P. Lovecraft cosmic horror: that of a woman. If Lovecraft was repulsed by any person not exactly like him (and, more than a few stories suggest, by himself too), Anchorhead burrows inside that feeling as the subject of repulsion. Everything that happens in this game happens through the lens of being a cisgender woman: a marriage with an increasingly taciturn and brutish husband; a town full of secrets and covetous glances; a horrid occult ritual concerning, inevitably, the protagonist’s womb. Gentry’s prose is lush, intimate, but precise in an uncommon way. He never takes the wrong linguistic lessons from Lovecraft, keeping the accumulation of detail but clearing off the thick bramble of self-regarding verbosity and obnoxious tics. Anchorhead is headily atmospheric, involving stuff; there is little else like it. [Astrid Budgor]

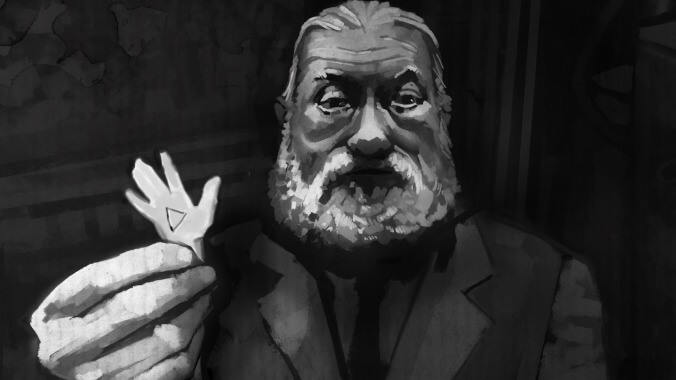

Until Dawn’s co-writer, Larry Fessenden, has a long and messy relationship with horror cinema, and it shows in the work, which is as close as gaming’s ever come to a playable B-movie slasher flick. As a consequence, Until Dawn is filled with a host of unlikable characters, cheap fake-outs, and deranged, over-the-top acting (especially courtesy of Peter Stormare, who spends most of his screen time hamming it up straight into the camera). It’s also terrifying, because every time one of these poor dumb kids dies, it’s on account of you, the player, screwing something up. Add in a legitimately brilliant mechanic that simulates tense moments by forcing you to hold the controller incredibly still, and you’ve got a recipe for the cheap, effective kind of cinematic mayhem that horror fans crave. [William Hughes]

The sequel is perhaps a better game, cleaner and more, erm, fleshed-out, but the original Dead Space was the scarier creation, with its silent protagonist and endless stretches of rust-colored corridors. You play as an engineer trapped on a derelict spaceship, the crew of which has been either transformed into scurrying, bloodthirsty “Necromorphs,” enlisted in an apocalyptic cult that worships them, or murdered. The jump-scares come early and regularly, but their effect is to set the player on edge as they slowly trawl through the deep-space mining rig Ishimura. The game’s commitment to this setting is absolute, from the flickering loading bays to its central combat mechanic, in which you use repurposed mining tools to strategically dismember enemies. This ends up being the scariest thing of all: The knowledge that you can’t just fire blindly at whatever might pop out of all those ominous, hissing vents, instead being forced to determine which appendage is the most deadly. [Sam Barsanti]

Horror is a function of powerlessness—the inability to protect yourself, to fight back, even to see the thing that’s after you. Amnesia: The Dark Descent gets that, on a gritty, fleshy, fundamental level. Even when you’re not running from literally invisible monsters—as in the game’s most celebrated sequence, a bit of sewer-set terror that would earn it a place on this list all by itself—Amnesia is the kind of game where the mere act of looking at the things pursuing you is harmful to your character’s rapidly dwindling mental health. Instead, you’ll skulk through the darkness, uncovering the linkages between Lovecraftian madness and some very human evil, and never once feeling powerful or safe. [William Hughes]

Horror and action fight for the wheel in every chapter of Capcom’s gloriously overstuffed pulp adventure. Through hedge mazes, clock towers, and besieged cabins, Resident Evil 4’s newly liberated camera chases agent Leon Kennedy, spinning with him when he wheels around to shoot the wriggling tendrils erupting from his pursuers’ necks. Raccoon City’s musty corridors unfold into Spain’s village squares and great halls, and a franchise founded on slow anticipation and shock turns into a series of protracted last stands against swarming, head-faking foes. The ridiculous thing about Resident Evil 4 is that it shifts gears from combat gauntlets and schlocky to full horror so successfully. Little in the Resident Evil series works on the player like 4’s crooked parasite wolves or its endgame autopsy rooms, where gasping Regenerators plod slowly after you. After all its oddball digressions, Resident Evil 4 can just snap its fingers, and the fear is back. [Chris Breault]

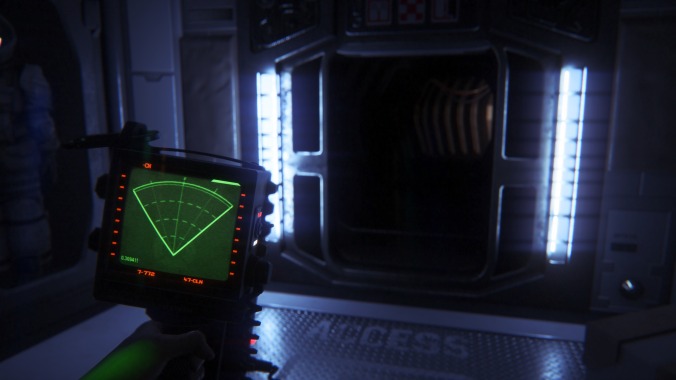

You can hear it walking. Stalking back and forth across the halls of the space station, its razor-sharp tail idly flicking. It knows you’re here, somewhere, and it wants you dead. Alien: Isolation captures, with resounding precision, one of the most resonant fears in modern pop culture: being chased by the Xenomorph from Alien, with nothing but your wits and a flamethrower running on empty. Set in a strange side corner in the Alien universe, starring Ripley’s daughter, it features a wily, intelligent, unyieldingly dangerous foe. The mood is oppressive and unrelenting, as hiding only ever brings you a temporary peace. The result is a game that understands better than its more official sequels what made Ridley Scott’s 1979 film terrifying. [Julie Muncy]

In a spatial sense, horror is often a descent. But while many games over-egg this architectural metaphor with Freudian basement after Freudian basement, Inside simply slopes the floor beneath your feet, so that any step forward, any progression, is innately linked to the idea of decline. Despite its fairytale, “lost in the woods” opening, Inside is a game about a lost society more than a lost person. Its horror is bluntly political, associative: a prose poem of structural oppression and industrial dehumanization with a deep underlying vein of historical atrocity. One of the more plainly disturbing of its many shadowed rooms simply contains a steaming mass of diseased hogs, rammed together, snuffling in the dark. As you leave it and trundle further down the slope, toward some kind of apocalypse, the game asks you to wonder: “Where does this end?” [Gareth Damian Martin]

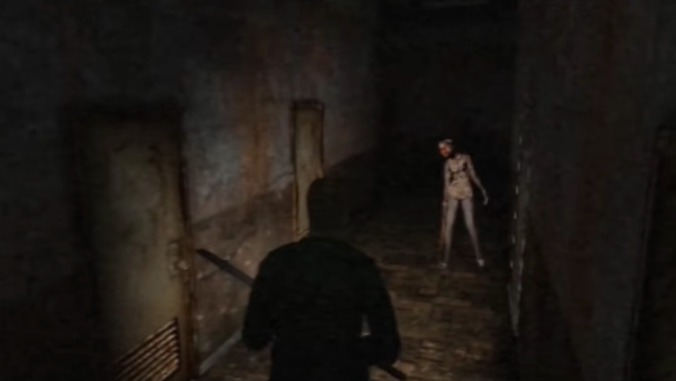

Take away the monsters, and the impossibly thick fog, and those mysterious air sirens that periodically coat everything in a layer of nightmare rust, and Silent Hill would still be one creepy-ass place: a drab American nowhere in perpetual decay, the kind of ghost town you can find in the forgotten back corners of every state. More petrifying than its predecessor and all but one of the sequels to come after it, Silent Hill 2 recognizes its titular environment as a psychic space as much as a physical one. The lurching, vaguely sexualized abominations you battle as James, a bereaved cipher dragged into danger by a letter from beyond the grave, could have emerged from the deepest recesses of the subconscious. And Silent Hill itself seems mapped according to a psychological logic, as though its city planners used a Rorschach test as a blueprint. The game’s celebrated ending might seem hoary and pat in another medium, an obvious twist. But in Silent Hill 2, actively playing your way to it gives the big reveal a charge of awful discovery: the video game as therapeutic odyssey, every riddle and locked door and dead-end street guiding you along a single path to a single inescapable truth. [A.A. Dowd]

In 2005, Resident Evil 4 arrived as a revolutionary and welcome change to the series’ over-appropriated brand of horror. But it also had the side effect of unfairly souring perception of elements that made its predecessors master classes in the aesthetics and orchestration of horror. One need look no further than the 2002 remake of the first Resident Evil to see just how brilliant the results can be when those concepts were pushed to new limits and emboldened by a new generation of hardware. The deliberately placed cameras and static, almost-Impressionist backgrounds allow for a stunning level of authorship that’s so often lost in modern games. There’s not a single ounce of design wasted aiming for simulation and realism. Every perfectly positioned shadow and dimly lit door, every Dutch-angled stairway ascent and unnerving foreground—it’s all lovingly tuned to create the most disorienting and nightmarish vision possible. If Resident Evil’s first incarnation had to fade away, at least it did so in a zombie-incinerating blaze of glory. [Matt Gerardi]

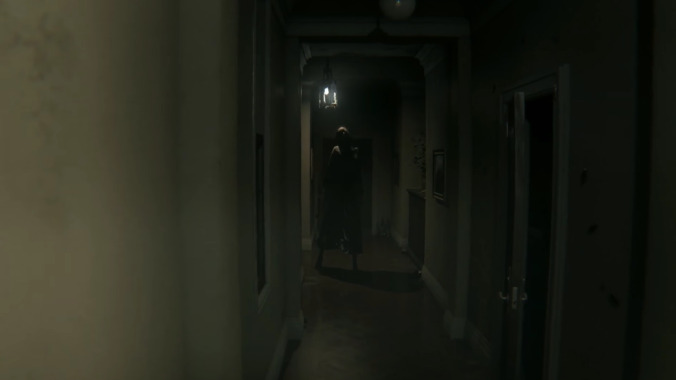

No horror game ever created has lodged itself so immediately and enduringly in the playing public’s mind as P.T. Its iconography—Lisa standing stock-still and stilt-legged in the foyer, a skinless goblin baby mewling in a sink—is as profoundly, riotously wrong as any in cinema, and its single stretch of hallway, looped forever in a gradual downward spiral, etches itself in the player’s mind like a trauma. But it is, more than anything else, the startling clarity of the game’s design that lingers in the memory: the way it reinvents the horror game by sticking to its roots. And so the tank controls of Resident Evil and sluggish combat of Silent Hill become, instead, a meticulously honed canter accompanied only by a button that lets you “look.” The abstruse puzzles of yore are turned into shattered, darkly comic jokes, like the “X” button’s single usage here. And the “monster,” such as she is, grinning and eye-gouged, is an agent of truly unfair, violent randomness, an unavoidable specter floating through the game’s code. Even the title is haunted by the ghost of a game never to be released. P.T. is a closed circuit of pure evil, glancing feverishly backward as it inches ever closer to the corner. [Clayton Purdom]

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.