The 52 most important American independent movies

In our attempt to assemble a list of the most important American indies, we have included works by mavericks, film school grads, and true outsiders

What makes an independent film? The question has never had a straightforward answer, and the cultural criteria that define an indie has changed over the decades. But by and large, it has always been something that couldn’t have been made within the Hollywood system. In our attempt to assemble a list of the most important American indies, we have included works by mavericks, film school grads, and true outsiders; productions with multimillion-dollar budgets and labors of love financed through part-time jobs; movies that played the arthouse, the grindhouse, or barely anywhere at all.

Some were massive box office hits, while others languished in obscurity for decades. Not all of our selections would rank among the best American independent movies ever made. Instead, the films on this list are the ones that broke new ground, created genres, or first introduced important artistic voices and subjects into American film.

While there have always been independent filmmakers and independently made films, for our purposes the American indie movement began in the 1950s. This is why we’ve decided to start our list with Morris Engel’s Oscar-nominated landmark Little Fugitive. We have also excluded documentaries (but not docufiction hybrids), entirely experimental movies, and any films that were directly financed with studio money (though not films that were subsequently distributed by major studios). And though the decisions have often been difficult, we have limited ourselves to just one film per director.

This list was last updated on July 1, 2022.

One of the earliest documentary-fiction hybrids, Little Fugitive ostensibly tells the story of a 7-year-old boy who runs away from home after mistakenly believing he killed his older brother. Once the kid arrives at Coney Island, however, the movie all but dispenses with narrative, simply following him as he wanders aimlessly around the boardwalk. Location shooting was still rare at the time, and few films of any kind had foregrounded casual observation to such a remarkable degree; among those who took notice were a group of Cahiers du Cinéma critics, who shortly thereafter started the French New Wave. [Mike D’Angelo]

John Cassavetes would go on to exert such a profound influence on the independent movement that any number of his films (including such later triumphs as , , and ) could have conceivably made this list. But since we’re limiting ourselves to one movie per director, we’ll go with his rough-edged debut feature, a drama about the lives of three Black siblings in beatnik-era New York. Developed from an acting class exercise and shot on 16mm by an amateur crew, Shadows tackled a challenging theme with an experimental, anti-Hollywood style, creating a template for generations of filmmakers to come. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky], , ,

Edward D. Wood Jr.’s magnum opus is a triumph of perseverance: its headlining guest star deceased, its cast and crew baptized in order to appease their born-again bankrollers, its screenplay a mystifying B-movie hash about extraterrestrials waking the dead as a warning to the self-destructive living. Wood’s faith in “dramatic license” meant nobody could persuade him that chiropractor Tom Mason was a poor physical match for the late Bela Lugosi—just the type of guileless strangeness that makes Plan 9 From Outer Space linger in the imagination. Such staying power drove the film’s word-of-mouth afterlife, boosting it from late-night TV dumping grounds to a half-loving, half-mocking tribute in the pages of 1980’s The Golden Turkey Awards, which declared Plan 9 “the worst movie ever made.” To the Tommy Wiseaus and Neil Breens who followed in its wake, the quintessential so-bad-it’s-good movie still cries out, “Future events such as these will affect you in the future!” [Erik Adams] (free), , , ,

In the early 1960s, experimental filmmakers worked alongside other insurgent American cultural movements, from the avant-garde art and theater scenes to the emerging queer and drug undergrounds. Shirley Clarke brought a lot of these strands together in her controversial The Connection: an adaptation of Jack Gelber’s play about hepcat junkies shooting heroin in a grubby apartment. The film’s subject matter—and its occasional profanity—made it hard to book, even in anything-goes NYC. But while fighting for The Connection in court, Clarke and her producer, Lewis M. Allen, helped start a cinema-changing conversation, arguing that movies should be more honest about how people live and talk. [Noel Murray]

The big studios wouldn’t dare touch the lurid output of Herschell Gordon Lewis, so-called and the originator of the red-drenched cheapies known as spatter pictures. He pieced the first such production together with spit, elbow grease, and gallons upon gallons of fake blood custom-ordered to get just the right hue. (“More Grisly Than Ever In BLOOD COLOR!” advertised the .) From a humble $25,000, Lewis and his bracingly vulgar new breed of horror scared up a staggering $4 million from drive-in crowds gasping and giggling their way through the sordid account of a homicidal caterer serving human bodies as tribute to an Egyptian goddess. Stab wounds would never be the same. [Charles Bramesco] (free), ,

Neither of director Michael Roemer’s excellent 1960s films—The Plot Against Harry and Nothing But A Man—were widely released until the 1990s. This was especially unfortunate for the latter, starring a pre-Hogan’s Heroes Ivan Dixon as a working-class Alabaman trying to make a better life for the woman he loves. A Jewish immigrant who fled Nazi Germany at age 11, Roemer transferred his childhood memories of bigotry and desperation to Black characters in the urban American South. He also struck a sweetheart deal with Berry Gordy to fill the soundtrack with Motown songs, crafting a vision of African American life more realistic and true to its time than slick Hollywood “race dramas.” [Noel Murray]Hulu (with Live TV),

Roger Corman started his career in ’50s sci-fi, but by the time the space race had given way to the Summer of Love, the B-movie impresario was in need of a new shtick. Ever adaptable, he turned his attention to the hippies on L.A.’s Sunset Strip and dropped some acid to get on their wavelength. With a script by Jack Nicholson and Peter Fonda in the lead role, The Trip made $6 million on a $100,000 budget and kicked off a wave of what Corman’s colleague Samuel Arkoff dismissively called “dope pictures.” Corman is less cynical about psychedelics, , “I had such a wonderful trip. If I based the picture on my trip, it would be propaganda for LSD.” [Katie Rife],

George Romero’s masterpiece of horror is a no-brainer for this list—and not just because the shambling zombies contained within would eat them all. Making back more than 250 times its $114,000 budget (and that’s just from the theatrical run), this black-and-white tale of desperate humans fending off the undead remains a deeply influential landmark of the genre, a National Film Registry inductee to which every zombie film since owes a debt. Sadly, it’s also influential as a cautionary tale: The original distributor failed to place a copyright on the prints, meaning it’s been reissued every which way in the public domain—and Romero didn’t see a dime from most of them. [Alex McLevy] (free), , ,

In 1967, an NYU film student premiered his first feature at the Chicago International Film Festival: a black-and-white drama about a nobody from Little Italy wrestling with the guilt and insecurity drummed up by his romance with a college girl. “A great moment in American movies,” declared a young Roger Ebert—strong words, but the next 50 years of Martin Scorsese films bear them out. Scorsese would only secure distribution after a sex scene was added and a title change instituted, but those who saw Who’s That Knocking At My Door could still see what Ebert did in the long takes, the pop songs on the soundtrack, the projected machismo, the crowd-control instincts in the slo-mo party sequence, and the saturated Catholicism. In concert with trusty companions Thelma Schoonmaker and Harvey Keitel, the film’s old doo-wop tunes were being carried by a once-in-a-generation voice. [Erik Adams], , , ,

Fifty years later, the cultural impact of Easy Rider still threatens to overwhelm the actual film. Dennis Hopper’s road movie about two drug-dealing bikers freewheeling across America mythologized an image of the nation’s counterculture from the communes to the acid, sparked a new wave of anti-establishment cinema (funded by the Hollywood establishment, of course), and epitomized the modern pop soundtrack. Hell, Hopper even took credit for America’s newfound love of cocaine. That’s an enormous burden to shoulder, and yet the film tells a smaller, more melancholic story than its zeitgeist-capturing reputation suggests: Two men, desperately trying to live life on their own terms, slowly realize that freedom is just another prison. [Vikram Murthi] (free), , , , ,

A film too ahead of its time to be appreciated in its time. Despite picking up an award in Venice, Wanda was dismissed by critics for its passive, aimless heroine, who deserts her family before taking up with a surly bank robber. Something of an anti-Bonnie And Clyde, it’s all Polaroid grit with none of the sexiness, no feminine verve or pluck—which is a big part of what would appeal to its small yet significant base of admirers in the decades to come. “I really hate slick pictures,” said one-time showgirl Barbara Loden of the film she wrote, directed, and starred in. “They’re too perfect to be believable.” [Laura Adamczyk],

Advertised with posters that screamed, “Rated X By An All-White Jury!” Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song burns with defiance. Disgusted by the Hollywood system after directing his one and only studio movie, 1970’s The Watermelon Man, director Melvin Van Peebles turned down a three-picture deal with Columbia to self-finance Sweet Sweetback, which as a film about “getting the man’s foot out of your ass.” The sentiment must have been going around, as the film shattered records everywhere Peebles screened it. And while Sweet Sweetback is often lumped in with the blaxploitation boom, it’s more accurate to say that those movies were biting the director’s style—minus the revolutionary fury. [Katie Rife]

Budget issues combined with a desire to buck the mainstream ensure that the story of American indies has largely been one of stripping, paring, reducing to an essence. Monte Hellman’s cross-country odyssey, in which two taciturn young men (James Taylor and Dennis Wilson—yep, the folk singer and a Beach Boy) in a ’55 Chevy race for pink slips against an obnoxious middle-aged dude (Warren Oates), pushed minimalism to a new, oddly mesmerizing extreme. Low on vehicular stunts and high on existential anxiety, the film is so self-aware that it ends by appearing to burn up in the projector. [Mike D’Angelo]

John Waters is as surprised as anybody he’s become a revered pop culture figure. He tried for decades to shock and offend the mainstream as often and as outrageously as he could, a mission that culminated in one of the most infamous moments in film history: Divine eating fresh dog shit in Pink Flamingos. Without that groundbreaking act of coprophilia, films like and would never have screened in mainstream theaters—which might actually have been for the best, depending on your point of view. But, , “Even if you hated” Pink Flamingos, “you couldn’t not tell someone about it,” a savvy observation that speaks to his gifts as a barker for the gloriously filthy carnival of his imagination. [Katie Rife]

Tobe Hooper’s visceral horror show was initially hyped like a grindhouse William Castle production, with dubious accounts of a sneak preview causing vomiting and fistfights. But this low-budget proto-slasher lingered in the public imagination, with annual re-releases in the ’70s and ’80s tuning audiences into its vision of dead-end Americans wreaking terrible havoc on their perceived countercultural enemies. (Sound familiar?) Texas Chain Saw has never been especially well-regarded as a traditional horror franchise; its influence goes deeper than its sequels, prequels, and remakes, down to a doomy, sometimes blackly funny outlook. Despite oddly beautiful cinematography, the movie still feels unruly and raw today. [Jesse Hassenger] (Free), , , , , ,

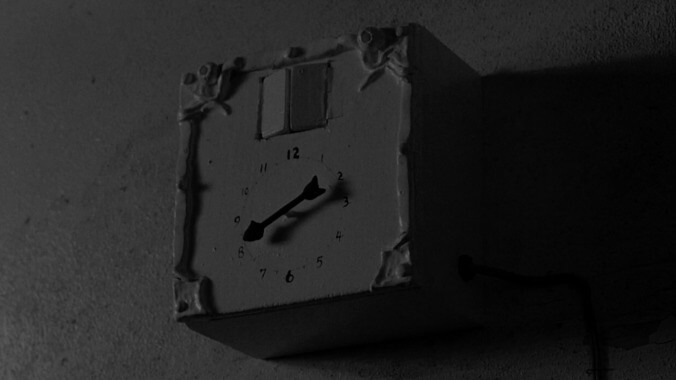

Before David Lynch was David Lynch, he was just another weirdo with a dream—more accurately a nightmare of urban decay, parental responsibility, and sexual revulsion, rendered in expressionist black-and-white. Begun as a student project at the American Film Institute, Eraserhead spent years in the making and went on to become one of the original word-of-mouth midnight movie sensations. The film attracted high-profile fans, but though Lynch briefly flirted with an unlikely Hollywood career (leading to the commercial failure of ), he would ultimately become one of the few filmmakers to grow into something like a household name entirely on his own terms. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky] , , , , ,

Shot over a year’s worth of weekends in the early ’70s, Charles Burnett’s remarkable debut feature—a collection of vignettes centered on a slaughterhouse worker from the Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts—technically didn’t receive an official theatrical release until the mid-2000s, due to long-standing issues with the soundtrack. But by then it had already circulated for decades in 16mm prints and bootlegs, influencing countless aspiring indie filmmakers with its impressionistic, neorealist depiction of working-class American life. It remains the most famous and celebrated work to come out of the loose collective of Black filmmakers known as the L.A. Rebellion. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

John Carpenter’s babysitter-in-peril thriller wasn’t the first movie to pit a psychopath against teenagers on a major holiday. (, its Canadian cousin in primo suspense, got there a few years earlier.) But it was Halloween, starring a 19-year-old Jamie Lee Curtis, that proved the real profitability of the premise: The shoestring shocker made $80 million, spawning a franchise still chugging along today and also a whole calendar’s worth of big-screen copycat killers in dime-store masks. Decades removed from the slasher heyday, Halloween’s influence still glows like a jack-o’-lantern in the window; you can see it in any horror movie with a good sense of widescreen space and hear it in the tinkle of every throwback synth score. [A.A. Dowd], , ,

Like other indie filmmakers who’ve focused on something other than the lives of white men, the late director Kathleen Collins was plagued by distribution woes, and was underappreciated in her time. The difference was that Collins’ time was the early 1980s, when a movie as passionate and personal as her Losing Ground should’ve drawn more attention. The tale of a philosophy professor and her painter husband going through a crisis in their marriage during a summer in the country, Losing Ground is a colorful and sensual story about the Black intelligentsia, and unlike anything produced in its era. Sadly, Collins died in 1988, just when American cinema was starting to open up for a talent like hers. [Noel Murray]

Given that by five people crossing El Salvador in a van in the middle of a civil war, it’s pretty incredible that Gregory Nava’s refugee drama El Norte was even finished, let alone that it made it into theaters. But the miracles don’t stop there. There’s also the film’s luminous cinematography, which would be impressive even in a big-budget movie, and the remarkable performances from leads David Villalpando and Zaide Silvia Gutiérrez, both newcomers at the time. But El Norte’s most extraordinary impact was on the conversation about immigration in America, prompting changes to U.S. foreign policy regarding Central American refugees. How many scrappy independent productions can claim that? [Katie Rife] , , , ,

A prizewinner at Cannes and the Sundance Institute’s first indie-centric US Film Festival (still some years from changing its official name), Jim Jarmusch’s wry deadpan comedy was, for better and worse, the ground zero of indie quirkiness, irony, and cool—a model for any number of subsequent success stories with offbeat, retro-fixated characters and considerable hip quotients. Not that these films embraced the Zen minimalism of Stranger Than Paradise. While Jarmusch himself belonged to the punk generation, his early films helped set the stage for the video-store-schooled fantasies of generation X and a long line of indie directors who saw movies as a way to create worlds of their own tastes. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky], ,

Imagine two brothers who’ve never set foot on a feature film set showing up on your doorstep and saying, “Hello, we’ve got this trailer, can we project it on your wall? Then maybe you’ll invest in our darkly comic thriller starring an actress you’ve never heard of.” Would you say no? If so, you just missed out on Blood Simple. This trailblazing neo-noir would be significant for its funding strategy alone, but it also launched the careers of Carter Burwell, Barry Sonnenfeld, Frances McDormand, and, yes, the Coen brothers. All off the strength of a trailer for a movie that didn’t exist yet. It boggles the mind. [Allison Shoemaker] , , , , , Hulu (with Cinemax)

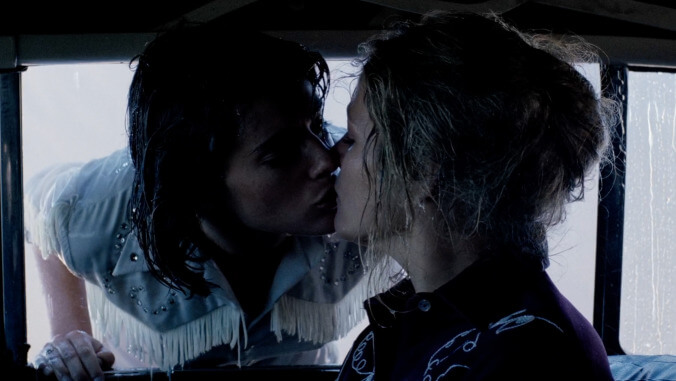

In a just world, Desert Hearts wouldn’t be groundbreaking. But in 1985, it was still audacious for an American movie to tell a love story between two women and to present their romance as one that belongs among the classics. Financed backer by backer with the help of early supporters like Gloria Steinem, Donna Deitch’s intimate drama zeroed in on every moment of repressed longing, shuddering release, and joyful discovery between the central pair. Most daringly, it offered a happy ending. “The inauthentic ones ended in a bisexual triangle or suicide,” Deitch . “Authenticity, in this case, means love.” [Allison Shoemaker], , ,

Even if Spike Lee hadn’t become one of the most provocative and creative filmmakers of his generation, his breakthrough feature, She’s Gotta Have It, would still be essential. This story of a promiscuous, independent-minded Brooklyn woman looks somewhat less sexually progressive now than Lee originally intended. But the vibrant vision of Black life in New York City—made at a time when nearly every African American character in New York movies was a pimp or a drug-dealer—is still thrilling to watch. With its jazzy score, its suitable-for-framing black-and-white images, and its quirky interludes of poetry, dancing, and one-liner comedy, She’s Gotta Have It showed that even films about “issues” could be delightful. [Noel Murray]

No one wanted to make Dirty Dancing. Writer Eleanor Bergstein and producer Linda Gottlieb shopped it all over Hollywood before finally getting a yes from Vestron Pictures, a Connecticut-based studio recently created by home-video producer Vestron Video as a way to produce their own original VHS content. But Dirty Dancing—with its abortion subplot and unapologetic title—stunned the big studios when it premiered in August 1987, becoming one of the biggest hits of the year and grossing $213 million worldwide. Vestron Pictures filed for bankruptcy in 1991, but its prized jewel remains one of the most quoted films of the ’80s. [Patrick Gomez] , , , ,

Drugstore Cowboy was only Gus Van Sant’s second film, after the low-budget . As he , “The independent film scene was becoming bigger and bigger,” everyone leaning toward trying “to make a film that was kind of mimicking Hollywood where the budgets were much bigger.” Adapted from the unpublished novel of the imprisoned James Fogle, the moody, mint-green-hued Cowboy proved audiences were ready for films like an unapologetic, poignant, and often funny look into the life of renegade drug addicts, complete with a resonate period soundtrack, Matt Dillon’s revelatory performance, and hallucinatory tripping sequences. Van Sant would continue to toe the line between mainstream and arthouse—through alternating projection or within a single one. [Gwen Ihnat] , , , , Hulu (with Cinemax)

Hal Hartley’s debut feature, an idiosyncratic romance between a brooding ex-con and a fashion model fixated on the nuclear apocalypse, laid the groundwork for one of the most staunchly independent careers in American cinema. Starring Adrienne Shelly, the actor most readily associated with his films, The Unbelievable Truth showcased Hartley’s heady mix of anti-naturalistic dialogue, modernist formal play, and emotional sincerity. Over the years, Hartley became something of an outsider figure, but the film’s signature scene, an exhilarating diner-set exchange where the dialogue loops around four times, remains the best illustration of his enduring, inimitable appeal. [Lawrence Garcia]

The one that changed everything. Steven Soderbergh’s debut feature (if you don’t count the Yes concert film he directed) won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, helped turn Miramax into a powerhouse distributor, and launched a major career that’s still going strong over 30 years later. But Sex, Lies, And Videotape’s true legacy is its seismic impact upon the small regional indie showcase where it premiered, which was then called the US Film Festival. Two years later, as a tsunami of talky no-budget movies hoping to replicate Soderbergh’s success poured into Park City, Utah, the festival changed its name to Sundance. [Mike D’Angelo] , , , ,

To paraphrase Brian Eno, not many people saw Slacker, but almost everyone who did tried to make a movie. Richard Linklater’s second feature—a Joycean tour of late-’80s Austin, seen through the eyes of a chain of bohemian misfits—all but catalyzed the American independent film movement of the ’90s and solidified a cheap label for the media to describe gen X-ers everywhere. Following its ascendency to cult film status, authentic-sounding conversation and mundane naturalism became creative currency among a certain class of filmmaker. While many tried to recapture the film’s spirit, Slacker endures precisely because it never strained for those qualities. They arose organically from a hyper-personal portrait of an eccentric, diverse community in flux. In other words, the film was lightning in a bottle. [Vikram Murthi], ,

Shamefully, 1991 was the first year a movie by an African American woman got significant theatrical distribution. That movie was writer-director Julie Dash’s artful, languid tribute to the unique culture in which she was raised: the Gullah of South Carolina’s Lowcountry region. In its time, Daughters Of The Dust was praised by critics but largely ignored by audiences. Its imprint has been profound, however: Beyoncé’s visual album draws heavily from the movie’s imagery, while filmmakers like Ava DuVernay have cited Dash as an inspiration for their own careers. [Katie Rife],

Todd Haynes’ Poison arrived at the height of the AIDS crisis and in part launched the movement that would come to be known as the New Queer Cinema. By interweaving three separate stories in varying formal registers, Haynes deconstructed stereotypes while depicting gay identity and desire in a more challenging light. Despite vehement opposition to the film from , Poison was met with critical acclaim upon its Sundance Film Festival premiere, marking the rise of independent films inspired by queer life on the fringes of society and anticipating Hollywood’s evolving, more empathetic treatment of homosexuality in the coming years. It also announced Haynes as a transgressive visionary to watch. [Beatrice Loayza] (free)

The much-quoted budget of $7,000 for Robert Rodriguez’s feature debut doesn’t do justice to the couple hundred grand Sony spent in post-production to get El Mariachi in shape for theatrical distribution. It does, however, reflect the DIY spirit and energy of Rodriguez’s scrappy, crew-light shoot-’em-up, and how it shifted perceptions of how much could be done with almost comically limited resources, presaging the coming digital era (which Rodriguez, of course, also embraced early on, even after moving on to bigger budgets). It’s also thematically appropriate to see the movie’s seven-grand-and-a-dream origins turn into the stuff of legend; much of the director’s subsequent work blurs the lines between tall tales and reality. [Jesse Hassenger] (free), , , , ,

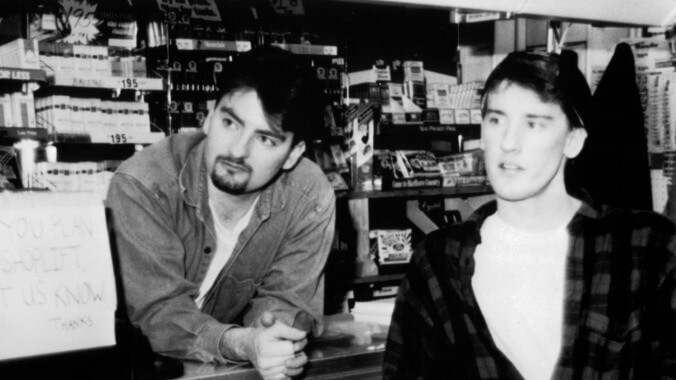

Kevin Smith famously considered Richard Linklater’s Slacker a text of permission—a work of art that let him know that he, too, could make a movie. But Linklater’s movie has dozens of speaking parts and an indie version of epic scope; just imagine how many folks must have been inspired by Smith’s revelation that belly-laugh comedy could be elicited by a handful of amateur performers talking shit and/or Star Wars. There may not be a lot of Clerks imitations hitting cinemas these days, but you probably have Smith to credit (or blame) for a whole lot of nerd-cult YouTube channels. [Jesse Hassenger] or Hulu (with Cinemax)

Although had already established him as an exciting new voice in sardonic film-geek pastiche, Quentin Tarantino didn’t become a Hollywood heavyweight until his second feature, a bona fide phenomenon that made more at the box office than any independent movie before it. QT’s nonlinear crime triptych didn’t just supercharge his career and revive John Travolta’s. For better or worse, it also inspired whole generations of aspiring hotshot auteurs to tell their stories out of order, pack their soundtracks with jukebox classics, and stuff their characters’ mouths with profane zingers and pop culture references. Possibly no other modern movie has so fully reshaped the film landscape in its own image; were this list ranked instead of chronological, there’s a very good chance Pulp Fiction would sit at the top. [A.A. Dowd] , , , ,

Before TV shows about teenagers like Skins and Euphoria envisioned every parent’s worst nightmare, there was Larry Clark’s Kids. Released in 1995 to great controversy for its frank depictions of sex and drug use, the film was denounced as child pornography by some critics, and praised as a necessary wake-up call by others. Written by a 19-year-old Harmony Korine, Kids approaches issues like sexual violence and addiction with unflinching, documentary-style realism, and it enlisted untrained actors to reinforce this image so unlike the feel-good escapism of teen comedies at the time. A gritty and unsettling portrait of urban adolescence, it ventured into dark and unexplored coming-of-age territory, expanding the boundaries of the genre in its wake. [Beatrice Loayza]

After cobbling together a meager budget for debut feature , Paul Thomas Anderson wrangled a healthier $15 million for his entrée into the indie big leagues. With his cobweb-shaped epic of the Valley porn scene’s transition from the ’70s to the ’80s, Anderson learned how to play industry ball; he came in hot insisting that his masterpiece be NC-17 and exceed three hours in length, but eventually backed down on both demands. Even so, nothing about his sprawling vision of surrogate family, striving, desperation, and redemption smacks of creative compromise. The film officially kicked off PTA’s reign as the crown prince of the American independent cinema, a streak still unbroken today, six triumphs later. [Charles Bramesco] , , , ,

Few films have offered a better return on their investment than The Blair Witch Project, whose ratio of cost to earnings is challenged only by one of the countless found-footage cheapies (see the title nine spots down from here) that arrived in its wake. How did a $60,000 horror movie shot in the woods of Maryland become a worldwide blockbuster? Credit a savvy and unprecedented viral marketing campaign, which launched supplementary websites to build buzz and feed into Blair Witch’s convincing illusion of snuff-film authenticity. It was the first definitive proof that the internet was the new frontier of movie advertising, and that there was a big demographic of very online audiences, waiting to be coaxed off message boards and into the multiplex. [A.A. Dowd] , , , , ,

Christopher Nolan’s first feature, (1998), scrambled chronology so vigorously that it was nearly impossible to, well, follow. Undaunted by its middling reviews and meager box office, Nolan then wrote a screenplay inspired by an unpublished short story his brother, Jonathan, had written, replicating the protagonist’s lack of short-term memory by telling most of the story in reverse order, with effect preceding cause. No distributor would initially touch it, fearing that it was still too confusing for a mass audience. Imagine both Chris () and Jonathan () today, doing the Nelson Muntz “Ha-ha!” [Mike D’Angelo] (free), , , ,

Andrew Bujalski’s debut feature is widely considered to be the starting point of “mumblecore,” which flooded American film festivals and arthouse theaters with chatty, semi-improvised, conflict-averse, dirt-cheap indies that mostly involved millennials navigating the prospects of early adulthood. Few of these movies seemed to have keyed in to the humanist instincts that Bujalski would develop in his subsequent films. But though mumblecore was always more of a catch-all trend than a concerted movement, its surprising longevity (and flexibility) helped bring forth an impressive and eclectic array of major talents, including Bujalski, Greta Gerwig, Barry Jenkins, Alex Ross Perry, and the Safdie brothers. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky] , , ,

There’s a timeline where this record-breaking romantic comedy, about the love life of a Greek American woman with a meddlesome family, became an . Instead, it went on to garner writer-director-star Nia Vardalos an Oscar nomination for Original Screenplay, and earn $241.4 million in North America, making it the highest-grossing rom-com of all time and spawning a cross-media franchise. Not bad statistics for a movie recently described by as a “small independent film with no big-name stars made for $5 million and put out in limited release in April.” [Patrick Gomez], , , , , Hulu (with Cinemax)

Sofia Coppola’s derided performance in The Godfather: Part III trailed her like a curse, but Lost In Translation—which she wrote, directed, and produced—dulled the mockery. Made for only $4 million, the comedy-drama brought in nearly $120 million, and Coppola won the Best Original Screenplay Oscar. After portraying Charlotte and Bob, unlikely friends plagued by loneliness in Tokyo, Scarlett Johansson’s and Bill Murray’s careers transformed, the former vaulting onto the A-list and the latter settling into bemused dad roles. Fan obsession over what Bob whispered into Charlotte’s ear at the end, as well as Coppola’s particular brand of sad-rich-people cinema, remains strong years later. [Roxana Hadadi] , , ,

It’s telling that when Zach Braff won a major award for his somber-sweet directorial debut, it was not an Oscar but a Grammy, for Best Soundtrack Album. Garden State’s carefully curated mixtape of Shins songs, old Simon and Garfunkel tunes, and indie hits lifted directly off of Braff’s iPod may not have changed your life, as Natalie Portman’s Sam promises, but it did set the sound of indie films for the decade to come. The movie itself—a meditation on one young white dude’s dead-eyed ennui—had its share of imitators, too. But it was its accompanying set of tracks that touched a chord with people, turning musical moping into a precision filmmaking art. [William Hughes] , , , , ,

In a better world, Primer would have launched Shane Carruth, its writer/director/producer/editor/head musician/star, into the indie-filmmaking stratosphere, if for no more than the sheer amount of science fiction mileage he managed to eke out of a minuscule $7,000 budget and a “time machine” prop so simple a child could build it in a lazy afternoon. Instead, Carruth has completed only one other film (the equally intriguing, if more expensive, ), and Primer remains a fascinating puzzle box, as intriguing for its singular expression of one man’s interests—technical jargon, unforeseen consequences, and the easily corruptible nature of extremely boring men—as for its infamously complex and obscure time-travel plot. [William Hughes], , ,

Sometimes it feels like American independent cinema has become one long search for the next Little Miss Sunshine. Following a family of eccentrics racing to a preteen beauty pageant in a bright yellow Volkswagen, this hit road dramedy premiered to much acclaim at Sundance, where it sold to Fox Searchlight for a then-record $10.5 million; it would go on to make that back tenfold in theaters, either triggering or hastening a sea change in dysfunctional onscreen clans, with the pricklier domestics of ’90s zeitgeist indies replaced by a cuddlier sitcom variety. Meanwhile, the bidding wars in Park City only intensified; every January now seems to bring a new chipper quirk-fest and an accompanying line of studio buyers eager to drop huge sums of money on it. [A.A. Dowd], , , ,

Blair Witch may have paved the found-footage way, but it was Oren Peli’s micro-budgeted haunted house story that demonstrated just how cheaply and efficiently you could make one of the best scare-delivery vehicles of the 21st century. With reportedly only $15,000 (at least before post-production), a single shooting location, and a mostly stationary generic home-video camera, Paranormal Activity became (arguably) the most profitable film ever made. Launching a subsequent six-entry franchise, it also built on the influence of Blair Witch, inspiring another giant wave of imitators to try their hand at no-budget horror filmmaking over the next decade. [Alex McLevy], , ,

Already a mainstay of the American indie scene from the mid- to late-2000s, Greta Gerwig first brought her signature charm to the Noah Baumbach universe in 2010’s . But it was Frances Ha, which she co-wrote and starred in, two years later, that turned their collaboration into a full-fledged partnership. While harking back to the spirit of the French New Wave, the bittersweet black-and-white comedy also looks forward, reinforcing Gerwig’s status as a major creative force in her own right, and anticipating the directorial successes that she would soon achieve with and . [Lawrence Garcia], , , , ,

Moonlight’s big victory at the Academy Awards will probably forever be associated with the . But it would have been plenty shocking to hear Warren Beatty just read the right title. After all, Barry Jenkins’ lyrical coming-of-age drama, told across three distinct chapters of a young man’s life, boasts the lowest budget of any Best Picture winner in history. What’s more, it’s the kind of movie—intimate, poetic, concerned with the lives of Black, queer, and impoverished Americans—that the Oscars have traditionally snubbed. Three years later, there are brilliant-blue glimmers of Jenkins’ triumph in plenty of new indie visions, including a few handled by A24, whose reputation as the boutique arthouse distributor of the moment solidified with Moonlight. [A.A. Dowd], , , , ,

So deeply has Get Out lodged itself in the cultural conversation—as a box office smash, as an Oscar winner, as the “social thriller” that turned writer-director Jordan Peele into a brand name unto himself—that it’s easy to forget its independent roots. This is the most galvanizing production so far from Blumhouse, a company that has become a horror behemoth by adhering to the indie ethos of giving ambitious filmmakers small but workable budgets and creative support. Some of the most provocative and influential independent films ever made have looked like genre exercises on the surface, a proud tradition that Get Out made even prouder. [Jesse Hassenger] , , , , ,

A feature film inspired by is about as original as independent cinema comes. , director Janicza Bravo’s bold yet faithful adaptation of Aziah “Zola” King’s viral retelling of two strippers on a trip to Tampa, turns all of the original story’s turns for the hellish and strange into filmmaking gold. She’s assisted by a riveting Taylour Paige, a terrifying Colman Domingo, and an outrageous Riley Keough, who seems to be embodying cultural appropriation itself. It all dances just on the edge of reality, keeping us thoroughly entertained and on the edge of our seats. As Shannon Miller pointed out in her , “a good story can come from anyone or anywhere, whether it’s told shot by shot or 140 characters at a time.” [Jack Smart], ,

American indie cinema breached the mainstream in a big way when 2016’s Moonlight won the Oscar for best picture; judging by , that trend shows no sign of abating. , Sian Heder’s remake of the 2014 French-Belgian film La Famille Bélier, became the first Sundance Film Festival premiere to take home the Academy’s top prize, beating out big-budget heavyweights and ushering in an era when streaming platforms like Apple TV+ can compete in the big leagues. Starring Emilia Jones as the titular child of deaf adults (played by the terrific daughter Troy Kotsur and Marlee Matlin), it’s a tale as modest as it is progressive in its depiction of disability, a reminder that there will always be an audience for heartwarming stories of families just figuring things out. [Jack Smart],

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.