The 8-hour genocide documentary Dead Souls justifies its mammoth length

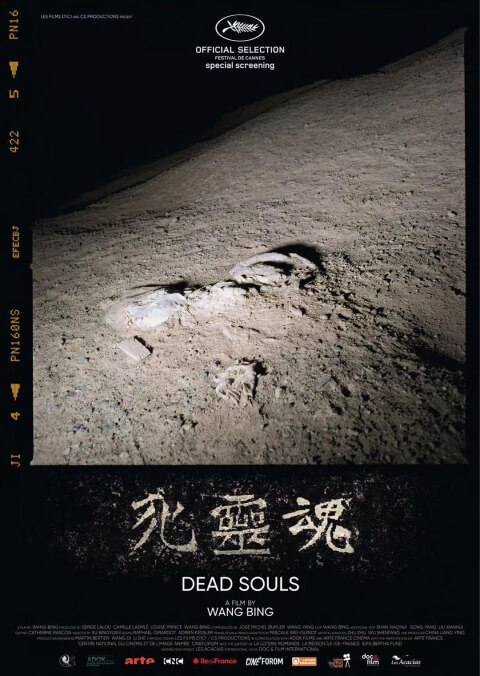

When filmgoers, professional ones included, complain that movies have gotten too damn long, they’re often talking about the increased bloat of blockbusters—a not unfair objection, in this age of supersized superhero epics. All the same, it’s a blanket critique that fails to take into account that some movies actually earn their protracted running times. For about the most extreme example imaginable, take Dead Souls, a new Chinese documentary that opens in New York today, and which runs a little more than eight hours total. That’s not a typo. When the film premiered at Cannes back in May, the head programmer announced that it was the longest official selection in the history of the festival. Now it’s being shown, at Anthology Film Archives, in three relatively manageable parts, each roughly the length of Blade Runner 2049. Even viewed in installments, it’s a monster time commitment. But Dead Souls, massive though it may be, possesses something that plenty of movies, normal-sized or otherwise, do not: an urgent justification for its existence, and also for its particular length. It’s long, in other words, for a really good reason.

Wang Bing, who dabbles in narrative but specializes in documentaries, has made even longer movies, if it can be believed. (His Tie Xi Qu: West Of The Tracks, which many consider a milestone of contemporary nonfiction filmmaking, runs an additional hour.) But here, he’s tackling something monumental and underexplored: the so-called Anti-Rightist movement, a campaign to deal with supposedly subversive dissent in Communist China. In 1956, the party had actually encouraged (some would say demanded) the open expression of opinions, even ones critical of the regime, during what came to be known as the Hundred Flowers Campaign. But this period of constructive criticism was short-lived, and it led straight into three years of punishment and censorship, as Chairman Mao Zedong ordered the political persecution of about half a million alleged “rightists,” a vaguely defined group of intellectuals and party members, many of whom had just been cajoled—and in a retroactive sense, entrapped—into speaking their minds. Some of those purged were shipped off to labor camps in the Gobi Desert for “re-education.” Most of them starved to death.

It’s a taboo topic in China even today, and one that Wang has explored before, in his 2010 dramatization The Ditch. But Dead Souls, which the director shot over a dozen years, is something more definitive and noble: the oral history of a genocide—a spiritual relative, in length and grueling subject matter, to one of the most significant documentaries ever made, the late Claude Lanzmann’s landmark Holocaust memorial Shoah. Wang, like Lanzmann, treats his camera like a witness. The film unfolds as a series of largely unabbreviated interviews with the elderly survivors of the camps, who regale Wang’s stationary, static lens with stories that have gone largely untold—or deliberately suppressed or distorted—in the half a century since. Some of these testimonials stretch into feature length, as the subjects explain what got them labeled subversives, and then recount, in sometimes disturbing detail, what it was really like in the camps, watching those who didn’t survive essentially shrink into nothingness.

Wang’s strictly, respectfully journalistic approach helps Dead Souls dodge the usual debates about genocide and representation. There’s nothing approaching a reenactment; breaking from the interview format very rarely (at one point, he trudges around the site of a mass grave—another device reminiscent of Lanzmann), Wang lets his interview subjects, seated in drab domestic spaces, paint a picture from their memories. Some, like the exiled party member whose musings fill the first hour or so, dryly and almost procedurally recount the ordeal, providing historical context. Others are intensely emotional in their unburdening. The storytelling ends up saying nearly as much as the stories themselves: Not simply capturing and filing memories, the film becomes a portrait of how these survivors have processed their trauma, how they’ve framed the horror of their experiences, and how they’ve coped with survivors’ guilt.

You could call Dead Souls an endurance test, and you wouldn’t be wrong, exactly: It will try patience and dampen spirits. But in his attempt to break silence, to give a voice to the unheard, Wang starts to get at larger truths about authoritarianism and how it really functions. For one, the almost absurdist machinations of the atrocity slip into sharper focus; among the more chilling topics of conversation is how Chairman Mao’s potentially offhand claim that only 5 percent of the party was bad apples inspired a dangerous quota—the need to place blame on that exact percentage of members, regardless if the “evidence” was there. A kind of dialogue unfolds across the various interviews, offering a cumulative, four-dimensional picture of the tragedy: This is how it can happen.

“Death was part of our daily lives,” one interviewee admits. “There was no point in being afraid.” By the eighth hour of heart-wrenching horror stories of life in the camps, a viewer might start to identify with his numbness. Wang doesn’t discriminate between anecdotes; he seems so humbled by the gravity of his material, by the need to let these survivors tell their tales without interruption and (usually) without interjection, that he exhibits almost nothing resembling an editor’s instinct. Which is to say, he’s left it all in, including plenty of overlapping remembrances, and not every sit-down is as fascinating as the next. Comprehensiveness, though, is really the whole point of a project like Dead Souls, which is more historical record—built on an imperative to remember and immortalize—than conventional movie. The revelation that so many of Wang’s interview subjects have died since talking to him only solidifies the value, the importance, of what he’s preserving. “No one wrote it,” someone says of this dark chapter in Chinese history. Now someone has. And if that’s not worth eight hours of your time, what could be?

Note: This is an expanded version of the review The A.V. Club ran from the Cannes Film Festival.