The A.V. Club’s 10 favorite books of 2018

Death, art, cults, zombies—the year in literature was as eclectic as it was excellent. There were crimes in need of solving, an infamous witch telling her tale, and a woman who just wants to sleep for a year. Characters have sex, they fall in love, and a bunch of folks get their heads chopped off (the undead meet just as sad of fates). Fiction, novels in particular, reigns on our list this year—with one under-the-radar book of essays sneaking into the top 10 and two master short story writers offering up instant-classic collections. As is so often the case, it was an embarrassment of riches in the book department. Here are our reviewers’ personal favorites from 2018.

The Largesse Of The Sea Maiden by Denis Johnson (Random House)

At a memorial service, the narrator of The Largesse Of The Sea Maiden’s title story is told he was the deceased’s best friend, information that comes as news to the narrator, who barely knew him. “Rather than memorializing him, we found ourselves asking, ‘Who the hell was this guy?’” A lesser writer would play the scene as tragedy, but Denis Johnson portrays it as yet another one of life’s endless curious circumstances, of which he was one of fiction’s finest chroniclers. Published eight months after the author’s death, the collection’s stories all circle around mortality in one way or another. Johnson proceeds almost casually, stringing together anecdote and incident, before making a big move, in an epiphany or a proclamation, including one of the best last lines in recent memory. A book that looks so closely at death is necessarily also about everything that comes before it: work, relationships, and always the passage of time. As one character puts it: “You make your own hours, mess around the house in your pajamas, listening to jazz recordings and sipping coffee while another day makes its escape.” [Laura Adamczyk]

I Wrote This Book Because I Love You by Tim Kreider (Simon & Schuster)

Tim Kreider makes love’s hardships—all those breakups, makeups, and fuckups—look easy. In I Wrote This Book Because I Love You, his second essay collection, Kreider pens long-form love letters to exes, including a groupie who works as a for-hire “pleasure activist,” a progressive pastor who embraces his atheism, and a circus performer who invites him on a Barnum & Bailey train ride to Mexico. He dives deep into mercurial relationships with his literary agent, a married friend, his mother, his star-crushed students at a predominantly female college, and his beloved elderly cat, all the while waxing personal on romantic love, lost love, Platonic love, divine love, friends with and without benefits love, the love for all creatures, and self-love. Yet, Kreider writes, “We have fewer words in our language to distinguish kinds of love than we do for distant cousins.” If love is all we need, Kreider shows us—tenderly and tragically—how to get there. [Rien Fertel]

The Gone World by Tom Sweterlitsch (Putnam)

The Gone World impressively balances tense, high-speed action with deep philosophical questions, resulting in a fast but thought-provoking read. The time-travel crime thriller asks readers to consider what they would do if they learned their lives were just a possibility, that they existed in a potential future that might never come to pass. Would you fight to preserve your existence even if it could cause disaster for other timelines or embrace the unknown and accept what would be a very different life? Other quandaries include: would you kill yourself to ensure humanity’s future, and if our species’ desire to understand the universe will eventually doom us because we don’t know how to stop when all signs point to disaster. Add in a genuinely unsettling vision of the end of humanity, a compelling cast of noir-inspired characters, and realistic interpretations of how new technology could shape society, and you have a novel with the power to haunt your thoughts long after you’ve finished reading. [Samantha Nelson]

Circe by Madeline Miller (Little, Brown & Company)

Doing for Greek mythology what Wicked did for Oz, Circe lets its titular witch tell her side of the story. While Circe’s most famous for turning men into pigs in The Odyssey, Miller’s book starts well before Odysseus lands on her shores, chronicling her pampered but neglected childhood as a daughter of the titan Helios, fraught relationships with her immortal family, discovery of her magic, and first interactions with the mortal world. Classic myths like the war between the gods and titans, the torment of Prometheus, the minotaur’s labyrinth, and the death of Icarus provide a familiar backdrop, but Miller beautifully embellishes them to show the cruelty of men and gods alike, weaving them together to build a coming-of-age story that explores the price of power and how legends are made. [Samantha Nelson]

My Year Of Rest And Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh (Penguin Press)

Ottessa Moshfegh’s second novel follows an unnamed character trying to sleep for a year. The saga is darkly comic, unexpected, and disquietingly grotesque—in other words, standard Moshfegh fare. “Since adolescence, I’d vacillated between wanting to look like the spoiled WASP that I was and the bum that I felt I was and should have been if I’d had any courage,” the woman explains. Much of the book’s unlikely pathos comes from the discrepancy between what the woman looks like on the outside—young, model thin, beautiful, wealthy—and the reasons she has for wanting to hibernate. She does this with a potpourri of prescription drugs obtained from New York City’s most negligent psychiatrist, and My Year Of Rest And Relaxation really picking up when the character starts taking “Infermiterol,” a drug that leads to entire days of blackout. It’s another acerbic character study from an author making a career out of bringing absurdly unlikable people to life. No one can discomfit a reader quite like her. [Caitlin PenzeyMoog]

Comemadre by Roque Larraquy (translated by Heather Cleary, Coffee House Press)

The mind-body divide becomes deliciously literal in Comemadre, Argentinian writer Roque Larraquy’s grotesque novel of art, lust, and ego. It’s not just the poor, doomed souls getting their heads lopped off in a sanatorium outside Buenos Aires—a group of doctors’ rivalry-fueled exploration of life after death—but nearly everything is doubled or split in two: There’s a pair of artist doppelgängers, a two-headed boy, and the complementary halves of the book itself. Meaning arises from external action, physical action, rather than turns within internal monologues. And so much happens: fires blaze, flesh decays, performance art is staged, and literal and figurative punches are thrown, to say nothing of all the severed heads and limbs. Layered without growing dense, the book is crisply comic, scenes punctuated like punchlines. That it all happens within a mere 130 pages is a sort of magic trick—the dizzying kind where a body gets sawed in half. [Laura Adamczyk]

The Incendiaries by R.O. Kwon (Riverhead Books)

R.O. Kwon’s debut novel is a potent story of obsession and religious faith. Those big themes are examined through the relationship between college students Will and Phoebe, who are drawn into the orbit of the charismatic, dubious John Leal, leader of a “Christian organization.” The Incendiaries weaves these three character arcs together through chapters that alternate among their point of views, and Kwon’s deliberate, sparkling prose is heavy with portending tragedy. One of the characters may be entering a cult—but is it a cult? Kwon keeps the reader unsure through to the very end, crafting a compelling page-turner that is still less interested in telling a sensationalistic cult story than it is in a deep and sympathetic probing of the appeals and perils of faith. [Caitlin PenzeyMoog]

Severance by Ling Ma (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Zombie stories may be played out, but the zombies in Ling Ma’s Severance suffer something more terrifying than being undead. These technically-still-alive people are trapped performing the routines they enacted mindlessly in their normal lives: endlessly setting the table for dinner, watching TV, driving to work, trapped in loops of the activities grooved into their brains by repetition. And though the zombie-like actions are thought to be the symptoms of “Shen Fever,” the disease seems to be communicable in psychological ways. Puzzling out the truth is just one of the pleasures of reading Severance, as Ma leaves much of the reality ambiguous. It is also a very funny book, skewering metropolitan millennial life and relationships. It centers on Candace Chen, a first-generation American whose life is slowly stripped away, first as New York City experiences an apocalyptic storm, then as its inhabitants succumb to the mysterious fever. Ma’s ending for Candace, through the power of that ambiguity, is one for the ages. [Caitlin PenzeyMoog]

The Collected Stories Of Diane Williams (Soho Press)

Few writers’ work truly merits descriptors like “original” or “unique,” words that mean less and less the more they’re used, but Diane Williams’ sentences are so singularly constructed as to call for hyperbole. As consistently surprising as her work is—akin to a tortuous hallway, wherein each blind turn might lead a reader to danger or delight—Williams is also a writer who seems to become more and more herself as time goes on. Part of the pleasure in reading her Collected Stories, more than 300 new and previously published (very) short fictions, is identifying a certain Williamsy-ness in the prose: the cartoonish sex, winking self-awareness, and sudden insights, bursting as fast and loud as a popping balloon—to say nothing of her ruthless concision and the abstract, unexpected language itself. “I was saying all of the appropriate things to everyone to get happiness from the happiness, to have a good time at the good time and I was getting it done,” one narrator notes. Dickinson’s mandate to “tell it slant” doesn’t get more slanted, or fun, than this. [Laura Adamczyk]

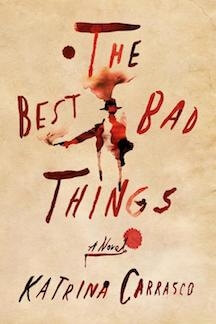

The Best Bad Things by Katrina Carrasco (MCD x FSG)

Katrina Carrasco’s gripping debut novel, The Best Bad Things, is essentially three books in one: a sexy noir, social critique, and historical fiction. That’s quite an undertaking for a first outing, but Carrasco quickly proves she has enough imagination to fill whole shelves. The author is as adept at building this 1930s world as she is a compelling mystery. Her protagonist, Alma Rosales, is one of the most fascinating and complex literary characters in recent memory. The hard-drinking, rabble-rousing Pinkerton detective enjoys a good fight (and fuck), as well as flouting conventions. She’s like the Hulk—the setbacks and beatings actually feed her desire to get to the bottom of her case. The whole experience is rather tactile; every time Alma’s masculine alter ego, Jack Camp, was sucker punched, I felt the wind rush out of me. The Best Bad Things is the rare book that should be savored, but is impossible to put down. [Danette Chavez]