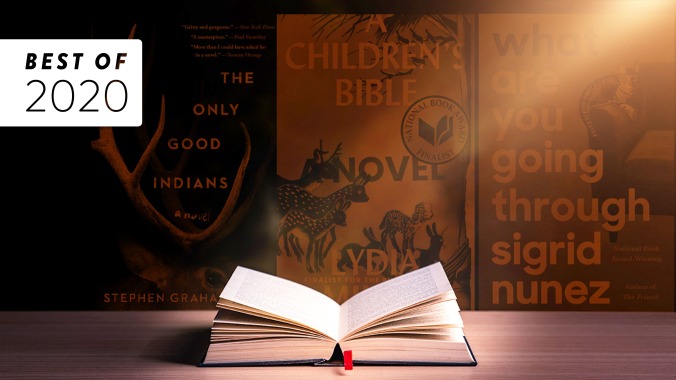

The A.V. Club’s 15 favorite books of 2020

A certain amount of escapism through books would have been more than understandable in 2020. (And by “a certain amount” we mean “a lot.”) You’d be forgiven for favoring the comfort food of a reread or a beach read. Or for not reading at all. Because for every person who was able to forget themselves in literature, who found books to be a refuge in this year where the news of the day and the light of our screens was oppressive and inescapable, there was another, if not several others, who was too bleary-eyed to even pick one up. So what’s perhaps most unusual about this year’s list of favorite books is just how usual it is. These selections—represented as individual favorites, rather than consensus picks for the year’s best—feel like the books we would have chosen regardless of all that was going on outside our windows. They’re a pair of dark, violent novels in translation. Incisive nonfiction that examines the powerful (and not so powerful) people working within the startup industry. Books that interrogate broad societal concerns like climate change, immigration, and right-wing extremism, and those that examine grief, nostalgia, and personhood within single individuals. These are books that look at difficult things, rather than turn away (but don’t worry, there’s some fun in here too). 2020 sucked, these books don’t. Thanks for reading.