The ambitious Mudbound gives a prestige literary epic the soul of a character study

Drawn from the pages of Hillary Jordan’s 2008 international bestseller, Mudbound has the heft—the narrative and thematic meatiness, the thicket of characters and subplots and years-spanning incident—of a book you can’t put down. But if the film is novelistic in its sprawl, maybe sometimes to a fault, it’s written in poetry as well as prose. For Dee Rees, writer and director of the tender (if dramatically overfamiliar) Sundance sensation Pariah, this handsome literary adaptation is a big leap forward in scope and craft—a sophomore swing for the fences. But Rees’ singular sensibilities haven’t dimmed with the expansion of her ambitions. They still glow brightly, illuminating Jordan’s vision of hardship, simmering conflict, and racial inequity in 1940s Mississippi.

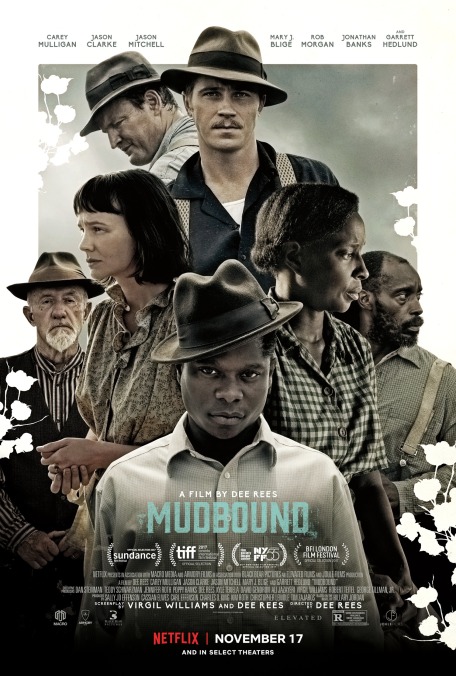

Mudbound entwines the fates of two families—one white, one black—tethering their hopes and dreams to the same unforgiving stretch of land. Chasing a kind of 20th-century manifest destiny, the emotionally limited Henry McAllan (Jason Clarke) relocates his wife, Laura (Carey Mulligan); bigoted father, Pappy (Jonathan Banks); and two young children from their home in Memphis to a cotton farm in the Mississippi Delta. For years, the land has been worked by the sharecropping Jacksons, country preacher Hap (Rob Morgan) and his wife, Florence (Mary J. Blige), raising their own family and nursing their own quixotic agricultural ambitions. The relationship between the two families is tense from the start, in part because Henry, the farm’s new owner, immediately establishes a rigid, demanding, employer-employee dynamic—one with implicit roots in the area’s antebellum past. “We don’t belong to them,” Hap insists early on, but uncontrollable weather, unforeseen injury, and inherent social disadvantage chip away at their autonomy.

Farm life isn’t easy for anyone, and the Jacksons locate occasional common ground with the McAllans in the shared difficulty and isolation of their ordeal, cut off from the world by floods, battling the elements and the stubborn inhospitality of the soil. They share another connection: two prodigal sons, back from the war. Henry’s cocksure ladykiller of a brother, Jamie (Garrett Hedlund, finally harnessing his swagger for a real performance), wrestles with PTSD—an anguish that does little to diminish the unspoken attraction between him and the bored, unsatisfied Laura. Jamie’s reappearance also coincides with the return of Hap and Florence’s eldest son, Ronsel (Jason Mitchell, boiling with resentment), who’s dismayed to discover that his overseas heroism inspires little gratitude or respect in racist midcentury Mississippi. Jamie, who flew B-25s, and Ronsel, who earned his stripes as part of George S. Patton’s famous 761st “Black Panther” tank battalion, forge a sad, touching friendship: two embittered veterans, bonding over booze, shared trauma, and a strange nostalgia for the front lines, where their lives at least counted for something.

Jordan’s novel traded off narrator duties chapter to chapter, decentralizing the drama to create a spectrum of perspectives. Rees and her cowriter, Virgil Williams, replicate this structure by providing each of the six leads their own running mental monologue. It’s the kind of choice that might irk show-don’t-tell sticklers, but besides amplifying the psychology of protagonists who often bottle what they feel, these eloquent voice-over musings also provide prestige material an uncommon interiority. (Imagine, for a sense of the effect, if it really mattered what the beautiful ciphers of a recent Terrence Malick movie were whispering to themselves and the Almighty.) Rees uses a balance of points of view to emphasize an imbalance in privilege. Shepherded to the screen by a black female filmmaker, Mudbound acknowledges not just how capitalism deepens the divides between all marginalized people, but also how misfortune trickles down, leaving some more disadvantaged than others.

Rees achieves a throwback widescreen grandeur—acres of rural scenery, immersive period dress, even WWII battle scenes—on a relatively tight budget. More often than not, her resourcefulness only enhances the intimacy of her approach. Whereas limited means may account for the decision to shoot the dogfight scenes from a tight vantage—rarely straying outside a restrictive view from the cockpit—it also keeps the focus on Jamie’s emotional crucible. Likewise, the earthy tones of Rachel Morrison’s digital cinematography bring out the grubby squalor of life on this veritable Southern frontier, stressing the first three letters of the title. Rees has preserved her debut’s delicate sense of detail, especially in regards to the performances, which are small and precise, pinpointing nuances of character against a larger historical canvas. When Laura narrates that “Violence is part and parcel of country life,” Mudbound keys in on examples (a chicken losing its head) and the city slicker’s silent wrestling with that reality. As in Pariah, attention is lavished on expressions of private struggle: Mulligan’s growing tempest of conscience, Mitchell’s battle against his wounded dignity, even the hints of crippling insecurity Banks peppers onto Pappy’s repulsive, bitter intolerance.

Southern Gothic love triangle, coming-home drama, portrait of the segregation era in all its ugliness—whole movies could be pulled from Mudbound’s tangled tapestry. At times, the film buckles a little under its ambition; even at close to two and a half hours, there’s a lot of ground to cover, and characters sometimes disappear for stretches, some individual arcs waylaid by others. (Mulligan’s Laura, for example, starts out looking like the heroine, but ends up playing a less significant role in the backstretch.) Rees hurtles these warring kin fatalistically forward, to a climax that’s harrowing not just for the awfulness of its violence, but for what it says about the American character: Circling back to its first scene, Mudbound suggests spinning wheels, cycles of abuse, and inequality even in tragedy. If the endgame is tough to bear, the getting there is rarely less than involving, thanks to the sensitivity of Rees’ staging. She’s made an economical epic with an intimate modern soul.