The American Friend is a Tom Ripley movie that doesn’t need Tom Ripley

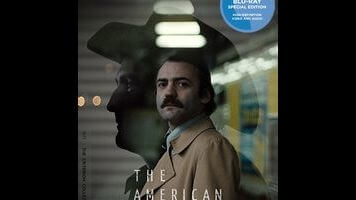

The movies have done reasonably well by Patricia Highsmith’s most celebrated character, the smiling sociopath Tom Ripley. He first appears in The Talented Mr. Ripley, which has been adapted twice, in both French (1960’s Purple Noon, with Alain Delon) and English (Anthony Minghella’s 1999 version, starring Matt Damon); opinions vary on which is superior, but the mere fact that there’s a credible argument to be had underlines how strong both films are. The same is true of Highsmith’s third Ripley novel (out of five), Ripley’s Game: Critics generally admired the 2002 adaptation, featuring John Malkovich as Ripley, but some felt that it paled beside Wim Wenders’ 1977 take on the same material, The American Friend. That last one joins the Criterion collection this week, and if it fails to live up to its high reputation—a subjective matter, to be sure—that’s mostly because neither Wenders nor Dennis Hopper, who plays the title role, appears to have a solid idea of just who Tom Ripley is.

To be fair, Ripley isn’t The American Friend’s protagonist. Most of the movie is told from the perspective of Jonathan Zimmermann (Bruno Ganz), a Swiss-born German man (he was a Brit in the novel, Jonathan Trevanny) who runs a small business making frames for paintings. Introduced to Ripley at an auction, Zimmermann refuses to shake his hand, having heard rumors about his involvement in art forgery—an element that’s actually taken from an earlier novel, Ripley Under Ground. Ripley, who’s deeply offended, takes his revenge by suggesting to a French gangster friend (Gérard Blain) that Zimmermann, who suffers from an unspecified blood disease (leukemia in the book), would be the perfect assassin. Using forged medical records, they manage to persuade Zimmermann that he’s on death’s door, and that killing a couple of alleged thugs on commuter trains will allow him to leave some money to his wife (Lisa Kreuzer) and young son (Andreas Dedecke). The only trouble is that Ripley grows to like and admire his prey.

Or that’s the idea, anyway. Ripley’s Game draws most of its emotional weight from the relationship between Ripley and Trevanny, which culminates in a powerful act of self-sacrifice. In The American Friend, by contrast, Ripley and Zimmermann barely seem to be on polite head-nodding terms, even after multiple scenes together. Hopper appears only sporadically for the film’s first 90 minutes, and never remotely resembles the character as written; Highsmith reportedly despised the performance when she first saw it, and while she later changed her mind, it’s not clear why, since Ripley’s malevolent cunning remains largely hypothetical here. Instead, Wenders opts to make him iconically American by having him wear a cowboy hat for almost the entire movie—a shrewd visual touch that can’t fill the void in Hopper’s uncharacteristically bland turn. When Ripley suddenly shows up to help with Zimmermann’s second hit, the gesture comes out of nowhere, and Wenders has to devise a completely new ending, as Highsmith’s would make no sense. This is a Ripley movie in which Tom Ripley’s presence seems all but irrelevant.

Fortunately, The American Friend is often a first-rate Zimmermann movie. Ganz inhabits the mild-mannered picture framer with the soulful warmth that would serve him so well a decade later as the angel in Wenders’ Wings Of Desire, making Zimmermann an anxious, empathetic figure who turns to crime solely as a means of providing for his family. (Think Walter White during season one of Breaking Bad, before the slow transformation into Scarface.) And Wenders handles the two assassination set pieces masterfully enough to make one wish that he’d gone Hollywood and directed a whole series of ice-cold thrillers. The film’s cutting (by Wenders’ longtime editor, Peter Przygodda, who died in 2011) is arrestingly arrhythmic, frequently ending scenes on an off beat; weird touches abound, like a shot of a stranger collapsing on an airport’s moving walkway—witnessed by Zimmermann, who ignores it—which is never referenced again. Remove the American friend from The American Friend and it becomes at once more intriguing and less frustrating. Perverse as it sounds, what game this movie possesses has little to do with Tom Ripley.