The B+ career: 10 artists who always deliver very good—but never truly great—work

This week’s question comes from The A.V. Club’s online culture editor, Clayton Purdom:

What artist (author, musician, director, actor… hell, even painter) do you always like and think delivers good work but never rises to the level of greatness?

Clayton Purdom

Curren$y’s debut album, from 2009, was called This Ain’t No Mixtape, as if to differentiate the effort from the string of mixtapes he’d just peeled off. Among the 50-plus albums he’s released in the past decade, though, he’s shown an unwavering commitment to uniformity, each fitting the Curren$y mold: a dozen or so tracks of breezy soft-rock weed-rap lorded over by the endlessly affable, laid-back Louisiana emcee. He raps almost exclusively about the good life in terms of high-grade weed, fiscal security, and luxury lifestyle items. Every single one of these albums ranges between “pretty good” and “very pretty good,” even the so-called classics in the catalogue, like the Pilot Talk series or the Alchemist collaboration Covert Coup. Occasionally big-shot guests show up, emerging from the cloud of weed and lounge samples as if from a dream. It’s hard to imagine what a definitive Curren$y record would even be at this point, so gobsmackingly consistent and unambitious has been his entire body of work. He just keeps showing up, rolling up, and rapping, one rock-solid effort after another—greatness defined by consistency.

William Hughes

I’m going to open myself up to lot of simultaneous “Wait, you like that?” ridicule on one side, and “YOU DON’T LIKE THAT ENOUGH” indignation on the other with this, but I think the Kingdom Hearts games walk this line perfectly. For a series with such an eye-rolling premise—to wit: beloved cartoon characters Donald Duck and Goofy help a key-wielding anime boy fight evil with the nebulous power of love and rampant Disney nostalgia—the Square Enix mashup franchise still manages to consistently put out a surprisingly satisfying action-RPG. It’s impossible to take the game’s plots (which haphazardly bolt together Disney villains like Maleficent and Pete with video game word salad monsters like the Heartless, Nobodies, Unversed, and more) seriously, but that doesn’t mean it’s not fun to hit them all with a big ol’ fireball or giant, stupid key. After more than a decade of side games, the series’ official third installment is due out this year, and I’ll be right there, cheerfully skipping cutscenes and beating up Tron baddies with a satisfying thwack.

Caitlin PenzeyMoog

The Decemberists are an extremely solid band, and I hope the “B+ career” doesn’t come off as an insult, because a B+ is a very high grade (especially here at The A.V. Club). Their albums are like my favorite toast preparation—with plenty butter and blueberry jam—a consistently nice breakfast, easy to eat and satisfying. Some people would disagree. The differing levels of enthusiasm between my sister and me on the band’s greatness is why I thought of The Decemberists for this prompt in the first place. My “I really like them, but I don’t love them” attitude was highlighted when my sister, two of our friends, and I attended a concert during their Hazards Of Love tour. After playing through the album they ended the show with “Sons And Daughters,” using the song’s repeating chorus to rousing effect when they got the audience singing along. (Side note: The line “We’ll fill our mouths with cinnamon” haunts me, because that is an extremely unpleasant experience.) Eventually they brought some audience on stage. My sister and one friend ran to the front of the venue to clamber up with the band, ecstatic, while the other friend and I hung back, ambivalent. I’ll go to a show, but going on stage is too much.

Matt Gerardi

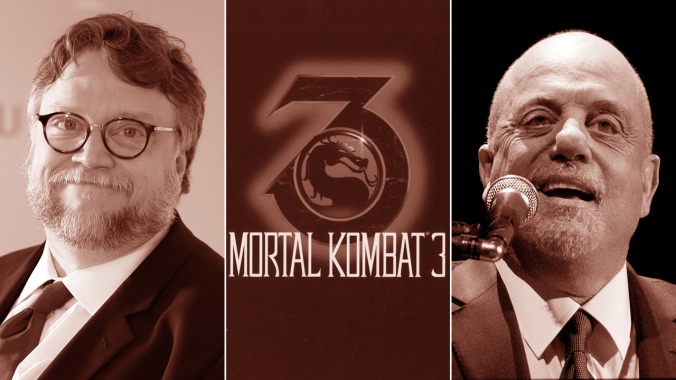

I have a deep love for Mortal Kombat, but as beloved as that series is, I’ve come to terms with the fact that I don’t think any of them are outstanding fighting games. The gore, cast, and mythos of the originals have aged into fine kitsch, but compared to their contemporaries coming out of Japan, I find them them to be stiff and just not all that fun to play. I’d say the series didn’t even approach greatness until 2011, when after a period of perfectly competent but forgettable 3D games, it went back to its 2D roots for a major reboot. That game and the sequel, Mortal Kombat X, at least felt halfway good to control, and it took huge steps forward for the kind of content fighting games can offer players who’d rather not compete online. Even then, though, I always enjoy my time with the story modes and practicing combos, but once I’ve had my fill, the series’ brand of herky-jerky fisticuffs just doesn’t stick with me.

Sean O’Neal

I’m always interested in a new Noah Baumbach movie. I’ve seen them all. I like most of them, and I even verge on loving some of them. But to me, they fall just shy of being truly great. Maybe it’s just that they’re too open about their influences: a pinch of Woody Allen’s intellectual neurosis, a dash of Whit Stillman’s detached urbanity, a lot of French New Wave and J.D. Salinger. But really, I think what keeps me from holding them in the same regard as those obvious forebears is that they all feel like slightly shaggy variations on the same theme of transition, as though Baumbach is still drafting and redrafting ways to tell the same story, and never quite achieving the profound human truths it’s suggesting. To misquote Tolstoy (and to sound like a pompous Baumbach character for a second), all of his unhappy families seem to be unhappy in the same way. They’re all filled with smart people in similar stages of arrested development, consumed by squandered opportunities and unrealized artistic ambitions and old grudges. Again, I like these stories; they’re filled with good-to-great performances (Greta Gerwig in Frances Ha, Jennifer Jason Leigh in Margot At The Wedding, even Adam Sandler in The Meyerowitz Stories), and all of them have their insightful and witty moments (if not much in the way of standout, quotable dialogue). Still, once I’m done I’ve never really been drawn to revisit them—not even Frances Ha, which I know Alex Dowd will give me grief about. To me, they never quite transcend the misery of their surroundings enough to make the film a journey worth taking again and again. But who knows? Maybe the next one will be truly great.

Erik Adams

I love Billy Joel, and have for as long as I can remember. I’ve paid way too much, multiple times, to see him in concert; I’ve picked up most of his discography on vinyl for mere peanuts. But the singer-songwriter behind “Piano Man,” “We Didn’t Start The Fire,” and “River Of Dreams” (and a couple dozen deep cuts that are much better than any of the ones that get played on the radio) is the quintessential answer to this question. It’s the animus that drives his career: that his McCartney-esque way with a pop melody will never get him mentioned within the same breath as Paul McCartney, that his sweeping, decades-long synthesis of the American songbook will ultimately come down to drunken tourists singing along to the broken dreams of a bunch of L.A. winos in our nation’s loudest and most antiseptic dueling-piano bars. Billy Joel is no Bruce Springsteen, and it probably doesn’t matter when poindexters like me and Chuck Klosterman argue that this is part of what makes Joel an interesting artist, but never a great one. The dude has sold millions of records, spends his summers filling baseball stadiums, is a member of the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame (inducted in the same class as Springsteen), and he’ll never get invited to sit at the same table as rock’s cool-and-critcially-acclaimed kids. But he also recorded The Nylon Curtain, which is as listenable and re-listenable as any statement record made by an aging baby boomer during the Reagan administration—with the exception of the cheesy Vietnam War ballad “Goodnight Saigon,” because even Billy Joel’s biggest swings must fall short of the warning track, which only increases my affection for him.

A.A. Dowd

Grab your torches and pitchforks, folks, because this going to be one of my least popular opinions ever, but Guillermo del Toro is B+ as fuck. It doesn’t really matter what mode the Mexican genre visionary is working in: From his franchise blockbusters (Blade II, the Hellboy movies) to his arthouse thrillers (Cronos, The Devil’s Backbone) to his prestige fantasias (Pan’s Labyrinth, this year’s Best Picture winner, The Shape Of Water) to that Netflix cartoon he created, del Toro doesn’t whiff. But he hasn’t made anything transcendently great either, and the reason for that, I think, is that all of his projects have more or less the same essential strengths and weaknesses: They’re triumphs of design—great creatures, great art direction, great costumes, great world-building—in search of better or deeper stories. I’m never less than dazzled by their craftsmanship, but that’s the only level on which they generally work for me. The good news is that those truly enchanted by the guy’s baroque fairytales and superhero spectaculars can just swiftly ignore the respectful, admiring, but unmoved “B” I hand to whatever he makes next.

Kyle Ryan

Early on, I suspect there were a lot of us who liked Wilco just fine. Post-Uncle Tupelo, the band’s two songwriters, Jay Farrar and Jeff Tweedy, embarked on rival paths that led Farrar to Son Volt and Tweedy to Wilco. The expectation was that Farrar, Uncle Tupelo’s primary songwriter, would rise to artistic prominence, and that was the case at first. But Wilco’s straight-forward first record gave way to grander ambitions later, until Yankee Hotel Foxtrot—and the drama around its creation and release—made the band a cause célèbre. I enjoyed that album quite a bit, but nothing that followed has captured my attention the same way. Tweedy is certainly an important artist, but listening to each new Wilco album feels a bit like eating my vegetables. I respect Wilco more than I like Wilco, which is probably enough to get me beaten up in certain parts of Chicago.

Nick Wanserski

Charlotte Gainsbourg makes intelligent, sincere, and witty music. She approaches unconventional subject matter, like the diagnosis of a brain injury she suffered water skiing, and makes catchy pop tunes out of them incorporating actual noises from an MRI machine. And yet I usually put on her music to act as the same sort of pleasant background ambience as jazz music at a restaurant. It’s not a knock on quality, but her breathy, ethereal vocals are unobtrusive and provide a pleasant mood that doesn’t need to be attended to. This is exacerbated by the consistency of her work. I’m always curious what her new albums will sound like, and they invariably sound exactly like a Charlotte Gainsbourg song. It’s not a bad thing by any means. As I say, I really like Charlotte Gainsbourg songs. It’s just that regularity also prevents any of her projects from especially sticking out.

Alex McLevy

When I picture the grade “B+” as a sentient being, it quickly coheres into a picture of a smiling Tom Cruise. Cruise is an actor who got to where he is in part by being the guy who is always going to give 100 percent—and then, when that’s used up, adds another 70 percent on top of it. He’s an attractive workaholic with a natural charisma in front of the camera (off-camera is a whole other thing), and is consistently strong in every film I’ve ever seen him in. Even projects that seemed like they were going to be far beyond his ken—anyone remember the fracas over his casting on Interview With The Vampire?—he ends up acing, delivering a rock-solid performance that often elevates the material. But it’s never exactly Oscar worthy. Even his flirtations with greatness (his supporting turn in Magnolia is likely his finest work) don’t quite achieve the heights of actorly perfection you expect from the giants of the field, your Daniel Day-Lewises and your Meryl Streeps. He’s not Nicolas Cage, see-sawing between greatness and disaster, and he’s not a reliable character actor just delivering solid work. He’s Tom Cruise: He’ll always be a really good actor, but I just can’t picture him delivering anything above a star turn—true greatness just beyond his reach. Maybe that’s why he uses so many apple boxes.