The Babadook is metaphorically rich—and pretty damn scary, too

He stands ramrod straight, in a pitch-black overcoat and matching top hat, like a scarecrow done up in Victorian evening wear. His fingers are unnervingly long and slender, his face as round and pale as the moon. And when he speaks, in a low guttural croak and through a crooked Cheshire Cat grin, it’s usually to utter his own horrid name, stretching out each syllable for dramatic effect. He is the dreaded Babadook—or Mister Babadook, to those who haven’t made his ghastly acquaintance—and not since Robert Englund first slipped on a striped sweater and brown fedora has a film conjured up a bogeyman of such primal, classical dread. Believe it or not, though, the real horror of this superb Aussie monster movie has almost nothing to do with the title fiend and everything to do with the unspoken, unspeakable impulses he represents. Remove the Babadook from The Babadook, in other words, and something plenty terrifying remains.

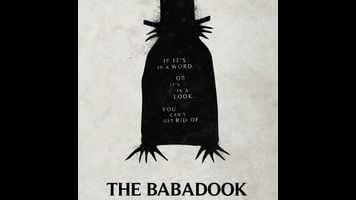

That something is right there in the strained relationship between a widow, Amelia (Essie Davis), and her troubled child, Samuel (Noah Wiseman). Samuel’s father died in a car accident, while rushing his mother to the hospital to give birth to him, and it’s clear from the opening moments of the film that the subsequent seven years of parenthood have been no cakewalk for Amelia. Her boy, possessed of a common but overactive fear of monsters, acts up at school and brandishes homemade weapons. Perhaps he’s merely absorbing and channeling the duress of his mother, who’s so scarred by the loss of her true love that she won’t let Samuel celebrate his birthday on his birthday. The situation goes from bad to much, much worse when Amelia discovers the world’s creepiest pop-up book, filed mysteriously into their home library; reading it aloud not only gives her high-strung son a new anxiety, but maybe provides him a real, supernatural reason to feel anxious. As the book warns, through nursery rhyme and disturbing illustration, “you can’t get rid of the Babadook.”

For seasoned horror fans, none of the subsequent groaning and slithering and paranormal dick moves will seem groundbreaking, exactly; if you’ve seen one shadowy specter scamper up a wall, you’ve seen them all. But writer-director Jennifer Kent, who cut her teeth on the set of Lars Von Trier’s Dogville, stages familiar bump-in-the-night material with upstart panache. The effects, many of them practical, are unfashionably herky-jerky, which lends them a frighteningly otherworldly quality. Furthermore, Kent shows an apparently innate understanding of how to escalate and sustain tension, and her feature debut is marked by moments of gutsy innovation, like a late sequence in which she inserts the Babadook into old Georges Méliès footage. (The well-dressed beast would certainly look at home in the silent era, alongside pasty German cousins like Nosferatu and Caligari’s somnambulist.)

What really distinguishes The Babadook, however, is the metaphorical potency of its narrative. The subtext isn’t subtle: Kent casts her eponymous villain as a manifestation of undigested grief and misplaced resentment—the ugly, repressed feelings the heroine takes out on her son, whom she unconsciously blames for the death of her husband. What the filmmaker is after, on some level, is an understanding of how someone like Susan Smith could have done what she did; ignore the lingering ghoul, and this is really the story of a mother and son wrestling, in a mutually destructive way, with shared trauma. That may sound schematic, and those who prefer their horror more purely irrational will balk at The Babadook’s almost therapeutic construction. But the movie has an emotional intensity uncommon to its genre, thanks mostly to its principal performance: Coming unraveled gradually, her stress curdling into abusive rage, Davis offers an alarming portrait of maternal affection pushed to its furthest limits. She’s scary great—and just plain scary. The Babadook, for all his storybook spookiness, simply can’t compete.