The Bachelorette got it right the first time and has been chasing that high ever since

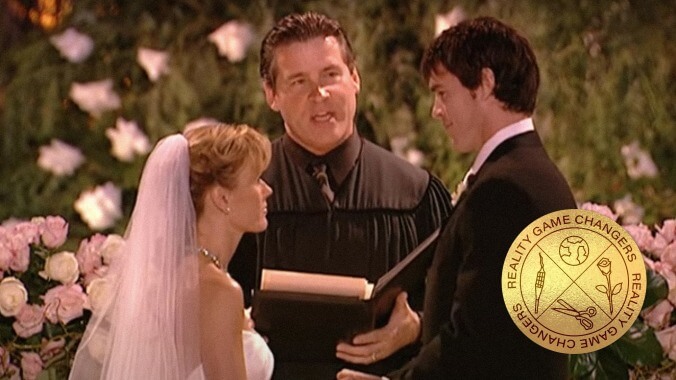

Image: Screenshot: Trista And Ryan's Wedding (ABC)

The Bachelor, along with its spin-off series The Bachelorette, is having one of its worst years since the franchise began. A long-overdue reckoning with the history of racial discrimination and white privilege on both series is taking place, and it’s not the one producers were hoping for. The first-ever Black Bachelor was meant to be a symbol of newfound commitment to diversity and progressive values; instead, continued problems with failed vetting procedures (and an equally big controversy sparked by longtime host Chris Harrison’s words in response) have highlighted the show’s seeming inability to move forward in any meaningful way from its long-established pattern of racially biased behavior and penchant for letting actual racists appear as contestants. The series can’t seem to nail its desired elixir of comfort-food appointment TV and watercooler-ready dramatics (for the right reasons, anyway, to borrow a common Bachelor phrase).

But in the case of The Bachelorette, the effort to return to a happier time of everything running smoothly has never gone away, not since the end of the very first season. Trista Sutter (née Rehn), the original Bachelor runner-up and star of the first season of The Bachelorette, gave the show exactly the fairy-tale narrative it was designed to deliver. So much so, that nothing since has lived up to the near-perfect combination of star and storyline Sutter brought with her. From start to finish (and well after), she gave the series its ideal “happily ever after,” and the program has been chasing that high ever since. There has been the occasional romantic success story to come from The Bachelorette in the intervening years, but none have come close to touching Sutter’s charmed outcome.

When The Bachelorette premiered in 2003, it was presented as the distaff version of a parent program that already had a clearly defined formula. The Bachelor, which had premiered the year prior, took one man, introduced him to 25 single and available women, and over the course of a season comprising group dates, one-on-ones, and artfully staged activities and games, asked the Bachelor to whittle down the potential love interests until there was only one left—one who, as directed by the series, would then receive a marriage proposal from the star. Each week would feature a rose ceremony, in which the Bachelor hands out roses to his chosen paramours; those who don’t receive a flower have to leave immediately. The whole experience normally lasts around two months—a pretty accelerated timeline in which to expect someone to discover (and commit to) their life partner.

Trista Rehn was one of the two finalists dating original Bachelor Alex Michel, until he broke up with her during the last episode, right before proposing to contestant Amanda Marsh. (In an especially cruel maneuver that producers used to insist on, the final contestants would have to walk up to the Bachelor and expound upon their love and willingness to commit, knowing full well there was a 50-50 shot they were about to be dumped.) But long before that moment, Rehn had become popular, thanks to a combination of wit, sensitivity, and old-fashioned telegenic charisma that shone through every time she was onscreen. The pediatric physical therapist (and one-time dancer for the Miami Heat basketball team) was a natural in front of the camera, able to convey breezy authenticity and relatable awkwardness in equal measure, like a reality-TV Jennifer Lawrence. Her personality (and popularity among viewers) made her a natural choice as the first Bachelorette.

Over the course of the inaugural season of The Bachelorette, Rehn delivered on the promise of that charm. Whether corralling a bevy of slightly intoxicated men through the halls of a Las Vegas casino or opening up about her vulnerabilities and insecurities during intimate romantic dinners, she commanded attention with confidence and grace, even (maybe especially) when faced with the sorts of awkward situations that generate the most conversation among viewers. (Which, back then, required phone calls or online chat rooms, thanks to the dearth of social media at the time.)

But even setting all that aside, producers couldn’t have engineered a more compelling narrative for Rehn’s romance journey if they tried. (And, as anyone who knows anything about these shows can attest, they try very hard, indeed.) As the season progressed, she gradually settled on two final men: Charlie Maher, a wealthy, blond financial analyst from Hermosa Beach, California, who embodied blue-blood birthright and espoused noblesse oblige; and Ryan Sutter, a besotted poetry-writing firefighter from Colorado. The choice between rich smooth-talker and soulful underdog couldn’t have been more stark. Love triangles in Lifetime movies wish they were so perfectly calibrated.

In the end, Rehn chose love over money. (Well, sort of; we’ll get to her cash reward shortly.) She and Sutter got engaged in the season finale, and less than 10 months later, the pair were married. That marriage served as a de facto epilogue to the season: A three-part special, Trista And Ryan’s Wedding, was broadcast on ABC, showing the couple’s idyllic home life and planning leading up to the big day. It was massively popular; 26 million viewers tuned in, the kind of numbers that don’t even exist anymore for TV programming. To get a sense of how much of a pop-culture touchstone Trista and Ryan’s romance had become, consider that not only did Oprah Winfrey offer to officiate their wedding herself when they appeared on her talk show some time after the Bachelorette finale aired, but Winfrey opened the program by admitting that attendance to the taping had become the most in-demand tickets in the history of her show.

In addition to finding love, Trista and Ryan’s romance paid off in other ways: By letting ABC film their nuptials, the couple had all expenses covered and netted a payment of $1 million dollars for the invasion of privacy. It was the first time many realized just how lucrative it could be to fall in love on screen for a reality TV program, an alarm klaxon for years of subsequent would-be influencers that there is sponsorship gold in them thar network hills. But it also set the stage as evidence for ABC’s longed-for ideal: that The Bachelorette (and The Bachelor by extension) works. Because unlike half of all marriages (and roughly 90-some percent of all Bachelor/Bachelorette engagements), Trista and Ryan Sutter worked. Every time the cameras came back around, every year or so, for a “Where Are They Now?”-style segment, the couple was smiling and at ease, seemingly as happy and in love as the day they chose each other. They have two kids, a stable and quiet life, and are approaching 20 years of wedded bliss. Regardless of any actual ups and downs they may have, in the eyes of America, it’s a Happily Ever After to beat the band.

And those two factors, both the result of Trista’s canny usage of media (and her undeniably likable personality), have created a template for what defines success on The Bachelor franchise that is almost impossible to top. By both succeeding at the openly acknowledged goal (find true, lasting love) and the not-so-acknowledged one (manipulate that success for immense profit), Trista Sutter has won her reality TV appearance in every way imaginable. There have been subsequent marriages from the series that stuck, though not many, and some financially remunerative careers made as a result of certain contestants’ savvy exploitation of their initially fleeting fame. But none have aced the series like its first Bachelorette—and given the rocky shores on which the franchise is currently foundering, no one seems likely to challenge Trista’s crown.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.