Porterfield, to his credit, is refreshingly allergic to bullshit. This is the fourth time he’s locked his camera on his native Baltimore, and though he’s inched away from the conditions of his earliest work—casting only nonprofessionals, working without a script—the filmmaker remains attuned to the rhythms, the spirit perhaps, of his hometown. As unstructured as its protagonist’s days, Sollers Point contents itself simply trailing Keith, fresh off a year of house arrest, as he motors around town in an oversized T-shirt: reconnecting with friends and foes, hustling for odd jobs, sparring with the local hoodlums determined to drag him back into his old line of work. Porterfield resists melodrama at almost every turn, and he handles the exposition organically, peppering it lightly into dialogue. (It’s revealed almost casually, through an encounter with a desperate junkie to whom he offers a ride, that Keith may not be entirely done with the drug business.)

Often shooting in carefully composed wide shots—a visual strategy carried over from his films with one-time cinematographer Jeremy Saulnier, who’s built quite the directing career of his own—Porterfield stages moments of quiet, revealing significance, like an early scene of Keith hanging in the doorway of his house, eavesdropping on a less-than-flattering conversation between his father (Jim Belushi, much less blustery than he was in Woody Allen’s Wonder Wheel) and his older sister. Perspective, both visual and dramatic, was key to his last movie, the sensitively observed I Used To Be Darker, which danced around the clichés and tropes of the indie divorce drama. But that film felt more achingly personal. And here, Porterfield doesn’t always sidestep so gracefully. There’s a faint After School Special vibe to every one of Keith’s encounters with his former accomplices, delivering grandiose speeches about “our neighborhood” when not issuing threats.

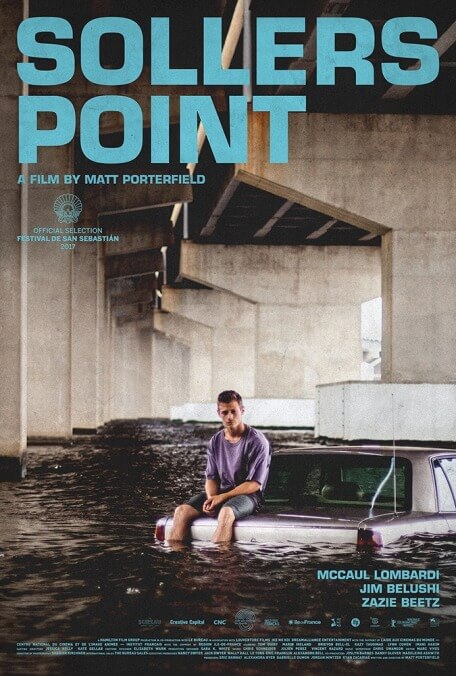

Lombardi, who previously snagged supporting roles in American Honey and Patti Cake$, has a credible presence—a riffraff nonchalance singed with hints of desperation and resentment. Blending in comfortably with a large cast of locals, he genuinely comes across as a product of this community. At the same time, and as written, Keith doesn’t reveal a whole lot of hidden depth, beyond some ill-defined artistic aspirations. Is Porterfield bumping up against the limits of realism? The character may resemble or even be modeled on any number of shiftless lost souls ghosting through life after incarceration, in Baltimore or elsewhere, but that doesn’t relieve the film of its responsibility to give him a spark of actual personality. Sollers Point is the kind of movie that often leaves you wishing you could spend more time with the foils—not just Belushi’s tough-love parent, struggling to get through to his uncommunicative, irresponsible son, but also the frustrated ex-girlfriend (Atlanta’s Zazie Beetz) who’s just about reached the limits of her patience and sympathy. It’s not a coincidence that the movie’s best, most moving scene is between these two; tellingly, it may also be the only one in which Keith himself does not appear.

So will he recidivate? Or is a sea change, a sudden emotional growth spurt, on the horizon? Sollers Point eschews resolution. There’s an integrity to its inconclusiveness, to its willingness to leave the audience hanging in the moment, stuck in the same unsatisfying limbo as the characters. But there’s also something vaguely self-defeating about that approach. Perhaps the wealth of unfussy cultural detail only throws the conventionality of this story into sharper relief. And maybe Porterfield’s restraint robs said conventional story of its potential power, denying us what a movie of this sort can deliver: if not the catharsis of a life reborn, at least the suspense of one teetering on the edge of a destructive backslide. Sollers Point is easy to admire, abstractly and on principle. But you may still leave wondering if a little melodrama, a little bullshit, might have been preferable.