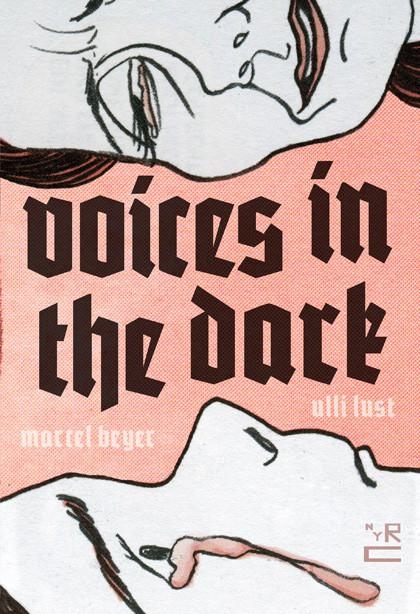

Voices In The Dark—at nearly 400 dense pages and overflowing with prosaic text—is an ambitious work. It’s Lust’s first long-form work of fiction, and she attempts to balance multiple perspectives, multiple timelines, and incredibly heavy subject matter. In many respects, she succeeds. Aesthetically, the book is striking and lush, and Lust provides ample opportunity to appreciate her ability to visually render subtle and complex emotions. Karnau’s obsessions draws readers’ attention to sound and its representation, and Lust offers some inventive and beautiful renderings of onomatopoetics, cacophonous shouting, and the wailing of bombs as they crash and bang throughout a city. The book is an all-around tremendous feat of illustration.

In other respects, however, Voices In The Dark fails to elevate itself above a mere collection of detritus. Individual scenes are moving, but the connections between them seem tenuous at best. The sequences from Helga’s perspective are particularly listless, and while they are the more sympathetic scenes, Lust fails to meaningfully interweave them with the Karnau passages that dominate the book. The two perspectives never quite mesh properly, and the disjuncture makes for a meandering and laborious reading experience.

The Karnau passages, taken on their own, offer distinct merits, but they also present problems. Here, Lust draws some of her most stunning, illuminating, and horrifying pages. Karnau, as Lust renders him, is almost a movingly tragic character. He is driven by obsession, dejected from society, and ridiculed by his peers. But, problematically, Lust also asks readers to divorce the figure of Karnau from any politics. His struggle is reduced to his psychological interiority, and little attention is paid to how that interiority relates to any political ethos. By the book’s end, Karnau has thrown his lot in with Adolf Hitler (at this point, living in a bunker and going insane) to avoid military service, and readers have watched him perform gruesome, nigh-unspeakable acts. He is not only a willing participant but a central actor in the Nazi’s plans to modulate the human race.

Readers are meant to sympathize with Karnau, to feel anything but contempt for him, but it becomes impossible. And consequently, readers are left with a disjointed narrative where the sympathetic character gets short shrift and the Nazi vivisectionist is the one left asking for some understanding.