The best comedy movies on Amazon Prime Video

The Farewell, igby Goes Down, Election, Young Adult, Friends With Kids, and more of the best comedies to stream on Amazon Prime Video

Streaming libraries expand and contract. Algorithms are imperfect. Those damn thumbnail images are always changing. But you know what you can always rely on? The expert opinions and knowledgeable commentary of The A.V. Club. That’s why we’re scouring both the menus of the most popular services and our own archives to bring you these guides to the best viewing options, broken down by streamer, medium, and genre. Want to know why we’re so keen on a particular movie? Click the author’s name at the end of each passage for more in-depth analysis from The A.V. Club’s past. And be sure to check back often, because we’ll be adding more recommendations as films come and go.

Some titles on this list also appear on our best movies on Amazon Prime Video list, but we decided comedy films deserved their own spotlight since they are often not included on our year-end lists as much as other genres. The criteria for inclusion here is that (1) the film is classified by Amazon Prime Video as a comedy (so don’t shoot the messenger if you think something is misgenred here), (2) The A.V. Club has written critically about the movie; and (3) if it was a graded review, it received at least a “B.” Some newer (and much older) movies will be added over time as Amazon Prime announces new additions to their library.

Looking for other movies to stream? Also check out our list of the best movies on Netflix, best movies on Disney+, and best movies on Hulu. And if you’re looking for a scare, check out our list of the best horror movies on Amazon Prime.

This list was most recently updated on January 30, 2024.

On paper, Julie Delpy’s 2 Days In Paris might well read like a light French farce, full of wacky characters and playful relationship banter that only turns serious toward the end of the film. The reality is much more raw. Playing a thirtysomething couple making a brief stopover in Paris after a vacation to Italy, Delpy (Before Sunrise) and co-star Adam Goldberg snipe at each other with casual venom, refusing to acknowledge or accede to each other’s calls for comfort or reassurance. When he says she’s special, she shoots back “Like in the retarded way, which is why I’m going out with you.” When she gives him more information than he wants about something, he says “It’s like dating public television.” They both seem a little neurotic and a little self-centered, but mostly, after two years together, they’ve apparently run out of reasons to be kind. And while their give-and-take is almost playful, both actors put an uncomfortable edge on it, fit to keep viewers squirming with alternate waves of sympathy and disgust. []

Affleck and his screenwriter Alex Convery think the well-known outcome of Air needs to be bolstered by the mechanics of a suspense narrative, crossed with a plot trajectory. And for a few scenes, Air feels like a gently satirical movie about corporate skullduggery. But it’s really a sports picture, where outcomes are determined by dedication, and a purity of purpose no one else can match. Damon’s Sonny is the scrappy and unlikely contender, whose love of the game gives him heart.Air will do well for Amazon, not only because it’s well-done, but because it’s selling a “true story” a lot of people want to hear, even if, to paraphrase Jason Bateman, a true story isn’t true until you put the truth into it. Ultimately, Air is about the battle for ownership of Michael Jordan’s likeness rights—one of the great business success stories of all time—and it’s told in an entertaining light, even if it’s not quite a layup. []

In American Ultra—a stoned, occasionally gruesome riff on , flavored with a touch of First Blood and —a small-town pothead lives blissfully unaware of his past as a brainwashed super-soldier, programmed by the CIA to be able to kill anyone using anything. Then, an intra-agency power struggle results in a termination order, and within a few hours our hapless hero finds himself in the parking lot of the Cash-N-Carry, having just killed two black-ops gunmen using nothing more than a dull spoon and a cup of ramen noodles, with no understanding of how he did it or why. Operating within the logic of severely stoned paranoia, he concludes that he must be a robot. American Ultra is one of those geeky genre mishmashes that’s very clever about being dumb. []

Few films on this list have had as massive an impact on the modern romantic comedy as Annie Hall. Woody Allen’s mid-’70s masterpiece set the template for contemporary rom-coms with a staggering degree of new twists on old formulas. From the fourth-wall-breaking tactics of Allen’s nebbish protagonist to the master class in editing, the movie serves as the crowning jewel on his decade as America’s foremost cinematic humorist, and captures essential truths about urban romance at the same time. [Alex McCown]

Siegel’s directorial debut, Big Fan, follows the world’s biggest Giants fan—played by Patton Oswalt—as he has an unpleasant encounter with his favorite player, and subsequently contemplates a conversion. (The character’s name, appropriately enough, is “Paul.”) Oswalt also wrestles with a potential sacrifice, suffers physical pain for the sake of his team, and even briefly changes his name. It’s hard to say whether Siegel intentionally laced Big Fan with Christian themes, or he’s just drawing on the common well of spiritual-crisis stories. Either way, Big Fan is clearly a movie of ambition, and not just a melancholy comedy about a football-loving schmuck who gets his ass kicked by everyone he loves. []

Interesting anecdotes don’t always make for interesting movies; your story may kill at parties, but that doesn’t mean it belongs on the big screen. In The Big Sick, stand-up comedian Kumail Nanjiani, who plays Dinesh on , and Emily V. Gordon, the writer and former therapist he married, dramatize the rocky first year of their relationship, with Nanjiani starring as a lightly fictionalized version of himself. That may sound, in general synopsis, like a story better told over dinner and drinks; besides friends, family, and fans of the the two co-host, who was clamoring for a feature-length glimpse into the couple’s courtship? But there was more than the usual dating-scene obstacles threatening their future together. Collaborating on the screenplay for The Big Sick, Nanjiani and Gordon have made a perceptive, winning romantic comedy from those obstacles, including the unforeseen emergency that provides the film its title. []

There’s something pleasantly nostalgic about . That may seem like a strange comment to make about the apparent novelty of a gay romantic comedy that widely released in theaters, but while it certainly leans into being a movie by and for gay audiences, it’s also a film that belongs to a tradition of studio filmmaking we don’t see much anymore. Co-writer/director Nicholas Stoller and co-writer Billy Eichner have set out to not just be an overdue “first,” but to be an established event in the cinematic canon of its genre, right up there with the likes of You’ve Got Mail and When Harry Met Sally. Only time will tell whether this film retains the staying power of those classics, but it’s a whip-smart, riotously funny attempt that certainly leaves a lasting impression. []

The left-field success of 2006’s Borat created a whole new set of problems for Sacha Baron Cohen: It’s hard to slip into loaded situations incognito, then slink away in a cartoon cloud of mischief and anarchy, when you’re behind one of the biggest pop-culture phenomena of the decade. Yet it’s a testament to Cohen’s genius as a professional chameleon and his devotion to staying in character that flamboyant creations like Ali G, Borat, and Brüno are arguably more famous than he is. Cohen wisely waited for Borat mania to cool down before launching a shockingly successful sneak attack on America in the form of Brüno, a chutzpah-rich feature-film vehicle for his sassy, scantily clad Austrian fashionista. Brüno finds Cohen traveling once again to our shores in dogged pursuit of the American Dream, circa 2009: becoming famous for no discernible reason. In his dogged pursuit of celebrity at all costs, Cohen attempts to seduce Ron Paul, horrifies a TV focus group by showing them a dancing naked penis, invites Paula Abdul to eat sushi off a fat naked man, and instigates a full-frontal assault on propriety and sexual repression. []

This feels like a second-shelf Coen comedy, particularly when compared to their no-less-shaggy The Big Lebowski. It might simply be that, unlike Lebowski, it lacks a strong protagonist, presenting a world of stupidly dangerous characters driven by unenlightened self-interest, without even Jeff Bridges’ voice of stoned reason. The final scene, which makes the end of No Country For Old Men look indulgent, concludes it all with a shrug, as if the silliness could stop whenever, so it might as well stop now. Which is fine. Burn’s land of the perpetually deluded works as an amusing place to visit, but an even better place to flee. []

Still Smokin’, their fifth effort remains an improvement on the previous films under just about every vector of criticism. This film finds director Chong tentatively experimenting with form and structure, devoting the first half of the film to a comic mishap that sends the pair to Amsterdam for a Dolly Parton/Burt Reynolds film festival, and then shooting the second half as a stand-up concert documentary. If stoner comedy has a Stop Making Sense, this would have to be it; there’s a winning sense of spontaneity to the grainy footage of Cheech and Chong’s onstage set, bouncing around the theater and employing the occasional distorted exposure to nod to their countercultural roots. More exciting still, Still Smokin represents the series’ first effort to actually tussle with legitimate thematic concerns, forming cogent thoughts beyond a desire for the nearest bag of Lay’s. Most of the first half plays out as a Q&A between the esteemed European press and our dudes, affecting a Godardian aloofness as if they had just been kicked out of Cannes for taking bong rips in the bathroom of the Grand Palais. They deliver some strong one-liners (“A lot of people say we’re just in it for the drugs, but that’s true,” Cheech deadpans) and more than that, they confront their own growing public profile with more self-awareness than in the literally self-aware flourishes. They lampoon their own cult of celebrity, but there’s a genuine unease beneath the jokes as they reconcile the stardom they stumbled into with the enduring desire to remain a toasty slacker forever. Chong mutters that “responsibility’s a great responsibility, man” in Next Movie, and those words ring loud and clear over his semi-reluctant fame. []

Beyond the eye-popping visuals, Chicken Run offers an endlessly clever extended riff on The Great Escape, recasting the German POW camp as a Yorkshire coop and allowing plenty of room for Park’s signature schemes and gizmos. Imagining Steve McQueen as one in a flock of rotund chickens with tiny legs and prominent teeth, the story begins with a hilarious montage of failed attempts by the plucky Ginger (voiced by Julia Sawalha) to escape Tweedy’s Egg Farm. Help arrives in the form of a brash American circus rooster named Rocky (Mel Gibson), who promises to teach the timid, earthbound creatures how to fly. Their plans become more urgent when the farm’s nefarious owner (Miranda Richardson) decides to boost sagging profits by running the fattened chickens through a giant pie-making machine. []

Freely adapted from the 1978 children’s book by Judi and Ron Barrett, the new animated movie Cloudy With A Chance Of Meatballs feels like a warning from another era, a parable about the perils of living amid abundance. But Cloudy—co-directed and co-scripted by first-time feature-makers Phil Lord and Chris Miller—doesn’t get too bogged down with moralizing. It flits swiftly between easy-but-funny sight gags involving gin food, send-ups of disaster-film clichés, and endearing characters brought vividly to life by a pleasing visual style, plus funny vocal performances from Bill Hader, Anna Faris, Bruce Campbell, and Mr. T. Hader plays a hapless geek with a lifelong gift for building inventions that almost work. His luck changes—and with it, the luck of his island town, whose sardine-based economy has been hit hard by the revelation that, as one headline puts it, “Sardines Are Super Gross”—when he unveils a machine that makes the sky rain whatever food he chooses. But the tremendous gift works largely to make his fellow citizens lazy, and it leaves Hader no happier than before, even with the arrival of a pretty weather reporter (Faris) who shares some of his nerdy obsessions. []

How do you come back from the phrase “Based on the Parker Brothers game”? Clue smartly incorporates elements of the game into a farcical structure that can sustain them and give the whole enterprise surprising legitimacy. It’s true that many of the comic situations, like the one above, are boilerplate, but even those who find Clue manic and unfunny have to admit that it’s a real effort, far more sophisticated in its design than its silly source might have suggested—or deserved. Director Jonathan Lynn and his co-writer John Landis are playful with the board-game references—divvying up the weapons like Christmas presents is cheerfully ridiculous, and giant envelopes play a prominent role—but they’re film historians first and foremost, and they use this opportunity to pay grand homage to genres that haven’t been in fashion for decades, if they ever were. []

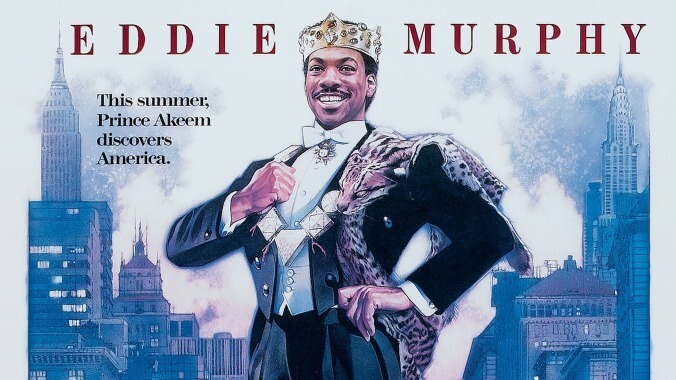

Coming To America is disarmingly sweet fish-out-of-water comedy in which Murphy’s good-natured African prince toils as a janitor at a fast-food restaurant in Queens while wooing the pretty daughter of owner John Amos. Eddie Murphy and sidekick Arsenio Hall—whose scene-stealing performance here seemed to promise a dazzling film career that never materialized—famously donned Rick Baker’s makeup to play multiple characters, but unlike in Norbit, the effect is sweet and affectionate rather than grotesque and scatological. Murphy would soon exhaust the comic possibilities inherent in donning layers of latex to become a one-man lowbrow vaudeville extravaganza, but his shtick still felt fresh here, probably because there’s an awful lot of heart hiding under all the prosthetics. []

On the surface, Richard Linklater’s day-in-the-life comedy Dazed And Confused seems nostalgic for late adolescence, when young people are still technically kids, but old enough to begin to experience some of the freedoms of adulthood. Set over the course of the afternoon and night of the last day of school in 1976, the film follows a few groups of friends as the joy of that first taste of summer gives way to conflict and a more nebulous existential concern. For all the scenes of kids drinking, getting high, and partying, Dazed And Confused is hardly a nostalgic look back at the good ol’ days—despite what the trailer below seems to promise. As Randall “Pink” Floyd (Jason London) says toward the end of the film, “All I’m saying is that if I ever start referring to these as the best years of my life, remind me to kill myself.” []

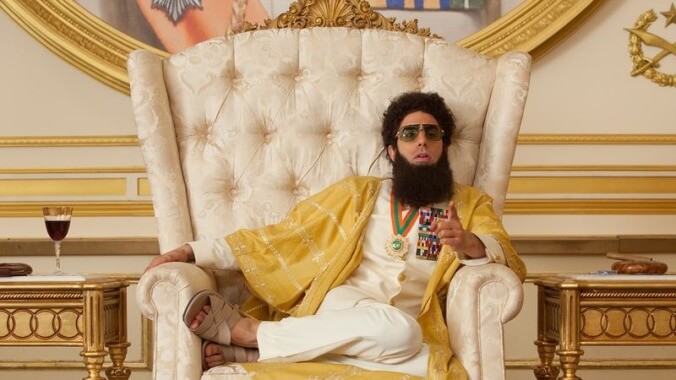

The Dictator keeps the gags coming as fast as it can manage, sometimes in big gross-out setpieces like an impromptu baby delivery, but more often in the general fusillade of hit-or-miss jokes that hit at a better-than-average rate. While Admiral General Aladeen certainly has a place in Baron Cohen’s gallery of human cartoons, the key point about The Dictator is that it’s a departure from his previous films and not another trip to the well. His needling instincts to shock and provoke are still present—and still merrily juvenile—but the film is both more conventional than Borat and Brüno and a more accommodating vehicle for different types of comedy. In reaching back to the past, Baron Cohen finds a viable way forward. []

For those who know Dr. Strangelove well, here’s a fun experiment: Watch it with the sound off, imagining that you’ve never seen it before, and try to determine at which point you’d realize that you’re supposed to be laughing. Stanley Kubrick, collaborating on the script with Terry Southern and Peter George, deliberately warped George’s novel Red Alert (originally titled Two Hours To Doom), turning what had been a deadly serious thriller into a black comedy. Equally inspired was Kubrick’s decision to fashion the movie’s visual scheme as if nothing had been changed at all. Apart from some mugging by George C. Scott (who was famously tricked into giving a much broader performance than he wanted to) and a few especially goofy moments in the last few minutes, Dr. Strangelove looks for all the world as if it’s telling the same sober cautionary tale as does Fail-Safe, the remarkably similar movie that was released just eight months later. Only the dialogue and some new, silly character names openly express the absurdity that Kubrick and company find in the doctrine of mutually assured destruction. []

This rambling cross-country journey makes a lot of familiar buddy-movie stops along the way, but seldom suffers for it. Directing with more focus— and eventually, more heart—than he brought to The Hangover, Todd Phillips smartly lets his leads’ chemistry power the movie. First seen wearing a Bluetooth headset to bed, Robert Downey Jr.’s character might have been a cliché of uptightdom in other hands, but Downey makes him a volatile bundle of anger and familial concern kept from exploding only by his desire to see the birth of his child. Zach Galifianakis, on the other hand, keeps his character interesting by refusing to define what type of weirdo he’s playing. His mere appearance is a contradiction: A burly man with an effete sashay and soulful (though glassy) eyes, his character lives on the tissue-thin line dividing helpless naïveté from the disarming confidence of someone who decided he was fine being a misfit long ago. The situations sometimes feel contrived, but the characters never do, particularly because Galifianakis remains simultaneously charming and unrelentingly irritating. It’s easy to believe Downey would come to feel for the guy, equally easy to understand why he’d want to throttle him with Galifianakis’ ever-present scarf. And the film benefits—both comically and emotionally—from leaving both possibilities look equally likely almost to the end. []

At some point in my youth I heard the old cliché that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” For me—and probably for a great many other dorks—this was a moment of great clarity. You see, as a veteran of many noble campaigns in far-flung realms, I was already familiar with the concept of a Beholder—a giant, nefarious living eyeball (also known as an Eye Tyrant or Sphere of Many Eyes) from the original , Gary Gygax’s hardbound collection of foes one might face in the world of (what was then called) Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. Lo! How this fiendish creature dwelled in my nightmares, ready to pounce should I ever let down my guard!With great excitement, though, I proclaim that l’essence du Beholder is redolent in the thrilling and enjoyable . The entire picture exudes the wide-eyed (some might say immature) wonderment found around slobbering beasts and magic spells. No, you absolutely do not need to know a thing about D&D to like this. But if you have a familiarity with the Forgotten Realms, the 1980s , or if you’re just a Led Zeppelin fan, there’s something here for you. Otherwise, there’s too much going on to ever feel left out.

Middle school is a nightmare. It’s like prison with homework, or a pitiless social experiment. For three very long years, half-adults with raging hormones and underdeveloped empathy glands prey on their peers, pouncing on any weakness, securing through cruelty their own place in the Darwinian pecking order. You don’t graduate from middle school. You survive it, if you can. Eighth Grade, the directorial debut of comedian Bo Burnham, has been made with a bone-deep and clear-eyed understanding of this unfortunate chapter of adolescence, and just how hard it can be for all but the most adaptive and impossibly popular. But the commiserative insight comes with an accompanying gust of warmth. What makes this coming-of-age film special is that it’s at once harsh and humanist: a perceptive, realistic comedy about tweenage life that’s also rich in compassion, that scarcest of junior-high commodities. [A.A. Dowd]

Alexander Payne’s Election centers on a divisive student-council race between three students, meant in the original Tom Perrotta novel as a sort-of echo of the 1992 presidential race, particularly the rise and fall of that year’s third-party candidate Ross Perot. But the film doesn’t really boil down to the competition that pits striver Tracy Flick (Reese Witherspoon) against popular doofus Paul Metzler (Chris Klein) and his wild-card sister Tammy (Jessica Campbell); from the beginning, it’s a face-off between Tracy and her teacher Jim McAllister (Matthew Broderick). The conflict starts off passive-aggressive, with Broderick’s student government advisor “Mr. M” claiming genial, student-friendly impartiality (as well as expertise in both “morals” and “ethics,” neither of which ever quite get defined in the film). But his problems with Tracy are evident from their first classroom scene, where McAllister leads his morals-versus-ethics discussion and quietly looks around for any student to call on but Tracy, whose focused, goal-oriented insistence gets under his skin. The hostility simmering underneath their early interactions comes to a boil in a terrific scene where McAllister accuses Tracy of destroying opposing campaign signs and she fires back without blinking. But this isn’t a movie of dramatic confrontations. Ambition squares off against corrupt would-be decency, and life goes on. So many movies about high school pit groups against other groups: jocks against nerds, mean girls against the unpopular, students against unfeeling teachers. In Election, the showdown between McAllister and Flick resonates because both characters feel so utterly alone—before and after. []

This maximalist sledgehammer of a film—something of a cross between Cloud Atlas, Enter The Void, Kung Fu Hustle, and a full season of Rick And Morty—has the energy, insanity, and exuberance of and the shock value of their “farting Daniel Radcliffe corpse” movie Swiss Army Man. Hopefully this serves as a warning that it is defiantly not for everyone. For those who revel in chaos, however, this movie is a gift. []

As with Ron Livingston in Office Space and Luke Wilson in Idiocracy, director Mike Judge centers the film around a put-upon everyman, played here by Jason Bateman, who watches his small universe collapse at his feet. Though his extract business is successful enough to win him a nice house and a pending takeover offer from General Mills, he’s having problems on two separate fronts. His sexual frustration at home leads him to make the drastic decision—encouraged by his dimwitted bartender (Ben Affleck, in top form)—to hire a gigolo to seduce his wife (Kristen Wiig) so he won’t feel guilty about cheating on her. Bateman is unaware, however, that the object of his desire, a fetching new temp played by Mila Kunis, is actually a con artist using her feminine charms to sabotage his business. []

If you’ve heard anything about The Farewell other than it stars rapper-turned-actress Awkwafina, maybe it’s the tagline: “Based on a true lie.” The lie in question isn’t a treacherous one, but it is illegal—at least in the States, where it’s expected that if you’re diagnosed with a terminal illness, well, you’ll be hearing about it. But in China, some follow a different protocol, perhaps a more merciful one, in which families carry the emotional burden by simply not telling a dying loved one that they’re dying. It’s an unbelievable practice from a Western point of view, but things aren’t as clear-cut when you’re standing with one foot in your native culture and the other in an adopted one. Lulu Wang’s sophomore feature captures this tension with tenderness and despair, revisiting the inter-generational family drama—the kind a pre-Hollywood Ang Lee specialized in—through the lens of first generation Chinese-Americans. []

First shown sitting around in his sweatpants, working through a trough of sugary cereal, Jason Segel doesn’t present himself as much of a catch, so his longtime girlfriend Kristen Bell can be forgiven for being disenchanted. A musician with dreams of staging a rock opera (with puppets) based on Dracula, Segel currently logs time composing the ominous music cues for Bell’s CSI-like TV show, but his lack of ambition hangs on their relationship like a lead weight. After Bell breaks up with him, Segel decides to unwind at the Hawaiian resort she’d always talked about, but awkwardness ensues when he discovers that she’s vacationing there with her new rock-star boyfriend (Russell Brand). However, Segel finds a sympathetic ear in the resort’s pretty customer-service representative (Mila Kunis), who helps him through his frequent crying jags. Forgetting Sarah Marshall could be pegged as yet another Judd Apatow tale of arrested adolescence, but Segel has always played more a serial monogamist than a horndog, and his earnest, self-deprecating screen persona graces the film’s crudest moments with a kind of innocence. He and director Nicholas Stoller also spread the laughs around to a fine ensemble, including Apatow regulars like Paul Rudd and Jonah Hill, 30 Rock’s Jack McBrayer as a spooked Christian newlywed, SNL’s Bill Hader as Segel’s reluctant confidante, and a scene-stealing William Baldwin as Bell’s smarmy, David Caruso-like TV co-star. []

“It’s authentically distressed,” says Allie (Clare McNulty) of the barrel she and her friend Harper (Bridey Elliott) find lying in the sand near the end of Fort Tilden. Like so many lines in Sarah-Violet Bliss and Charles Rogers’ caustic comedy, it’s a sharply double-edged observation. Not only is the chipped wooden container in question more genuinely weathered than the one the women had already purchased as a conversation piece before beginning their trip to the beach, but Allie’s observation also stands as a piece of inadvertently pointed self-analysis. Harper and Allie are indeed damsels in distress, and not just because they can’t efficiently navigate the way from a Brooklyn loft to the Rockaways (a disastrous, distended day trip to hook up with some boys, which makes up the film’s entire plot). They’ve been shaped by a parentally subsidized lifestyle that permits neo-bohemian arrogance without the threat of actual starving-artist poverty; their family ties simultaneously insulate them from harm while rendering them defenseless against the smallest challenges to their egos and routines. Far from the exercise in vicarious hipster-voodoo-doll skewering its basic setup suggests, Fort Tilden is at once less sentimental and more incisive about privilege and its discontents than the recent films of Noah Baumbach. It’s also funnier. []

While it’s true that most romantic comedies merely make minor tweaks to a rusted-out formula, it’s also true that many critics approach rom-coms with a sense of eye-rolling obligation, while solidly unspectacular movies like Lockout get praised to the skies. There’s formula in Jennifer Westfeldt’s directorial debut, but feeling as well. And anyone who thinks it’s far-fetched to see two friends of opposite gender agreeing to raise a child while they continue to date other people hasn’t touched base with single urbanites in their late 30s recently. (It’s absurd, but only by about 10 percent.) If nothing else, the film deserves endless praise for its bombshell kicker, a final line that blasts through the coy innuendo at the heart of most screen romances. []

Robert Carlyle (Trainspotting) stars as a laid-off Sheffield steelworker who devises an unusual scheme to better himself in this boisterous new comedy. Inspired by the popularity of a Chippendales appearance, Carlyle begins recruiting other unemployed men to form their own stripshow. That none of them, for various reasons, are really qualified to be taking off their clothes in public is the source for much of The Full Monty’s humor—most often in the form of some very funny physical gags—but the film has much more going for it than that one obvious joke would suggest. The Full Monty takes a harsh look at the state of post-Thatcher labor in Britain, portraying some of the humiliation involved with life on the dole. Carlyle’s attempts to win the respect of his young son, and some of the other men’s insecurity with their bodies—a rarely touched topic—are treated sensitively and incorporated seamlessly into the story. []

From the moment Hancock first introduces Will Smith as a drunken, glowering, foul-mouthed superhero, it seems clear that he’s eventually going to rehabilitate himself into the charming version of Will Smith, the one who became famous on the strength of wisecracks and a famously infectious grin. The movie telegraphs that change in the trailer and even in the first half-hour of action, as Smith’s hostile hero—who frequently causes millions of dollars in damages while sloppily foiling crimes in Los Angeles—meets PR man Jason Bateman, who offers him a major public-image makeover. But the obvious never happens. Instead, Hancock takes off at right angles, essentially turning into M. Night Shyamalan’s Unbreakable, as seen through the big action lens of modern superhero movies like Iron Man and the Spider-Man series. []

Heathers isn’t a perfect movie by any stretch: The heavily worked-over ending feels frantic and rushed, not the exclamation point it needed to be, and the dialogue occasionally crosses the line between clever and overly pleased with itself. (Call it “The Diablo Cody Threshold.”) Yet coming at the end of the ’80s, Heathers still stands out for questioning the prevailing stereotypes of teen movies rather than accepting them as a given. Two decades later, the Hughes model of teen comedy/dramas is still pervasive, but the goings-on at Westerburg High have only gained in potency, perhaps because so few movies have had the courage (or the approval) to follow Heathers’ lead. “It’s not very subtle,” as J.D. says, “but neither is blowing up a whole school.” []

High-Rise, a darkly funny adaptation by cult English director Ben Wheatley (, ) of the J.G. Ballard novel of the same title, preserves the book’s ’70s setting, steeping its vision of a toppling society in retro decadence. Dr. Laing (Tom Hiddleston, very good), a bachelor physiologist from apartment 2505, watches as the titular building regresses into a Mad Max-esque wasteland of garbage barricades, raiding parties, and literal class warfare following a few blackouts and a problem with the trash chute—a descent into collective madness that High-Rise underplays and elides to surreal (and audience-defying) effect. Wheatley’s use of ellipses and his overall refusal to do anything that might suggest a point of view or invite identification skirt incoherence. As in Ballard’s novel, the building isn’t just a dystopian microcosm of alienation and stratification, with the wealthiest living at the top. It also seems to create a new reality of its own: a killer cocktail of claustrophobia, stylishness, and oblique irony. []

Cast adrift in the loftiest realms of Manhattan, the disaffected young hero in writer-director Burr Steers’ auspicious black comedy Igby Goes Down is like a Larry Clark baby with breeding and a budget, free to test his limits without having to worry much about the consequences. From the opening scene, when Kieran Culkin and his older brother circle like vultures over their mother’s deathbed, Steers faces an uphill battle: Why should anyone care about a rich, sullen brat who spits the silver spoon out of his mouth? But once his novelistic script sets the film’s off-center, comically dysfunctional universe in motion, it stirs up great affection for a character whose very presence, by all accounts, invites more than his fair share of beatings. []

Because many of the best jokes in The Interview have nothing to do with North Korea, it’s worth recapping the ancillary mayhem that the Sony hackers would have suppressed. Franco stars as Dave Skylark, the foppish, airheaded host of a celebrity gossip program. He scores a coup when Eminem, on camera, makes an offhand announcement that he’s gay, prompting elation in the control room. Another of Dave’s scoops involves Rob Lowe’s coming-out as a secret bald person (“His head looks like somebody’s taint!” someone from the booth exclaims). But Dave’s producer, Aaron (Rogen), yearns for credibility. A larky call lands them an interview with Kim Jong-un (’s Randall Park, a worthy foil to his better-known co-stars), supposedly a Skylark superfan. Soon, the CIA turns up with a request that the two assassinate him. Much of the film is devoted to the hit-and-miss (but strangely moving) riffing between the leading men. []

An unusually eventful “couples brunch” among a neurotic group of bright, colorful friends is rudely interrupted by news of imminent apocalypse in It’s A Disaster, a droll social comedy about a party that takes a number of strange turns. It’s a smart, dark, tonally tricky affair about what happens when the bonds that hold civilization together come apart, whether through the impending divorce of a couple whose union helps keep a disparate group of friends together, or through some manner of dirty bomb or zombie attack. []

In Jeff, Who Lives At Home, plays a quintessential mumblecore fixture: the eternal adolescent whose life is locked in a holding pattern. Too old for a quarter-life crisis but not old enough for the mid-life variation, Segel lacks a rudder. But he does have a vague conception of destiny, which leads him in a series of surprising and then predictable directions. Segel begins the film with a wonderfully spacey monologue about M. Night Shyamalan’s , then sets off into the world in search of symbols and codes. He’s a spiritual seeker with a mind clouded with cannabis, and an animal decency that makes it easy to root for him, no matter how misguided his actions. Life changes for Segel’s 30-year-old slacker when his mother (Susan Sarandon) sends him to the store for wood glue. Before Segel can get it, he catches , the wife of his estranged brother , with another man, and reconnects with Helms to conduct a half-assed surveillance on her. Sarandon, meanwhile, receives mysterious messages from a secret admirer at work and contemplates giving romance another go late in the game. []

Rian Johnson’s witty and phenomenally entertaining whodunit may have been inspired by classic Agatha Christie adaptations, but its underlying story of fortune and upward mobility owes more to Charles Dickens (who had his own fondness for mystery plots). Explaining why, however, would involve spoiling some of the film’s crucial twists. After a famous mystery novelist dies of an apparent (but very suspicious) suicide on his 85th birthday, an anachronistic “gentleman sleuth” (Daniel Craig) arrives to investigate the family of the deceased—a rogues’ gallery of useless modern-day aristocrats that includes a trust-fund playboy, an “alt-right” shitposter, and a New Age lifestyle guru. Johnson, who made his name with geeky delights like and before hitting it big with , finds ingenious solutions to the rules of the murder-mystery movie formula. But more impressively, he manages to stake out a moral position in a genre in which everyone is supposed to be a suspect. []

The Ladykillers remakes a classic 1955 British film directed by Alexander Mackendrick and starring Alec Guinness as a grim would-be criminal mastermind whose can’t-fail heist encounters unwitting opposition in the form of a kindly old woman. Already as dark as London soot, the comedy hardly needed work to bring it in line with the Coen brothers’ sensibility, but the remake moves to a beat of its own, one unexpectedly in sync with the gospel music dominating its soundtrack. Playing a kindly, churchgoing widow prone to conversing with her dead husband and railing against the excesses of “hippity-hop music,” Irma P. Hall fills the old-woman role. Living in a house within convenient tunneling range of a riverboat casino’s none-too-secure vaults, she becomes the landlady to a self-proclaimed professor of Renaissance music played to white-suited perfection by Tom Hanks—who, under the cover of music rehearsals, begins working with a grab bag of criminals (Marlon Wayans, J.K. Simmons, Tzi Ma, Ryan Hurst) on a dig for the money. In his first truly comedic role in years, Hanks summons up an unforgettable caricature of Southern gentility turned foul, a creation well-suited for filmmakers who have made rich caricatures their stock in trade. []

One of the first things Aubrey Plaza says in The Little Hours is “Don’t fucking talk to us.” Anachronism, as it turns out, is the guiding force of this frequently funny, agreeably bawdy farce, which imagines what a convent of the grubby, violent, disease-infested Middle Ages might look and sound like if it were populated by characters straight out of a modern NBC sitcom. Plaza’s Fernanda, a caustic eye-rolling hipster nun born eons too early, sneaks out to get into mischief, using a perpetually escaping donkey as her excuse. Uptight wallflower Genevra (a priceless Kate Micucci) tattles relentlessly on the other women, reporting every transgression to Sister Marea (Molly Shannon, playing her dutiful piousness almost totally straight—she’s the only character here that could actually exist in the 1300s). And Alessandra (Alison Brie), the closest the convent has to a spoiled rich kid, daydreams about being whisked away and married, but that would depend on her father shelling out for a decent dowry. If the plague doesn’t kill them, the boredom will. When Plaza, Micucci, and Brie get smashed on stolen communion wine and perform a drunken sing-along of a wordless choral staple, like college girls sneaking booze past the RA and belting some radio anthem in their dorm, the true resonance of all this anachronism slips into focus: An itchy desire for a better life is something women of every century experience, regardless if their catalog of curses yet includes “fuck.” []

As a heist picture, Logan Lucky knows just how often to alternate straight exposition with cagey withholding. The full robbery blueprint is revealed slowly—new details are still twisting the narrative even after the big heist day has passed, perfect for Steven Soderbergh’s control-freak tendencies (once again, he shoots and edits himself). The snappy script by unknown (and possibly pseudonymous) newcomer Rebecca Blunt offers some Coen brothers-like dialogue, which Soderbergh complements with his compositions. Sometimes he gets a laugh just by how he positions the actors in the frame, and there are multiple gags predicated on the timing of explosions. []

The movie doesn’t waste a lot of time on setup: Director Robert Aldrich and screenwriters Albert S. Ruddy and Tracy Keenan Wynn introduce Burt Reynolds with a scene of him pushing a shrewish girlfriend around, followed by a car chase with the police, then a bar fight. Ten minutes into the story, Reynolds is in prison, and officious, American-flag-lapel-pin-sporting warden Eddie Albert is explaining the film’s premise. Albert runs a guard-staffed semi-pro football team, and wants Reynolds to coach and quarterback. Instead, Reynolds puts together a team of prisoners to give the guards a warm-up game, and through that team’s gradual assembly, the movie reveals Reynolds’ character, as well as his past as a former NFL MVP disgraced in a point-shaving scandal. Football aside, The Longest Yard draws mainly from Aldrich’s own The Dirty Dozen, plus existential prison pictures like Cool Hand Luke and I Am A Fugitive From A Chain Gang, where aloof anti-heroes gets punished beyond what their crimes demand. Reynolds takes on a game he can’t win (because the guards will make his stint miserable if he does), and can’t lose (because his fellow inmates will treat him even worse than the guards). The movie winds up being about small victories. Who can exploit whom, and who can inflict the most damage along the way? []

The Lost City, directed by Adam and Aaron Nee, is a good movie, but for inscrutable and ineffable reasons. The story is not particularly original, daring only in its Romancing The Stone mimicry. It isn’t shot with any sizzling style. Its dialogue is clever one minute, then whiffs the next. And yet! Anyone who watches this motion picture and says they truly disliked it is probably telling a fib. It succeeds because of one thing: star power. Hey, if it works, it works, and that’s likely what the producers said when the Nee Brothers’ rushes came back. []

Whit Stillman adapting Jane Austen feels at once apt and almost unnecessary. His previous films—obsessed as they are with manners, social status, and conversational diplomacy—come pretty close to fulfilling any need we might have for a modern-day Austen. ’s characters even discuss Austen at length, arguing passionately about Mansfield Park’s virtuous heroine and her relevance to contemporary readers. Some cinephiles may still feel exhausted, too, by the deluge of Austen adaptations that hit TV and multiplexes during the mid-’90s: BBC’s six-part Pride And Prejudice, Ang Lee’s Sense And Sensibility, Roger Michell’s Persuasion, the Gwyneth Paltrow Emma. (These all aired or were theatrically released within a 16-month period, believe it or not.) Still, it’s not as if movies today offer such a surfeit of wit and sophistication that one as purely pleasurable as Stillman’s Love & Friendship can be dismissed. If nothing else, it gives Kate Beckinsale, who previously starred in Stillman’s , a lead role that isn’t a vampire, and doesn’t require her to battle werewolves while clad in black-rubber fetish gear. []

In a perfect world, Anna Biller would be swimming in the kind of grant money that Cindy Sherman was getting back in the ’90s. But this isn’t and she’s not, so we only get a Biller film every half decade or so. (It takes a long time to sew all the costumes and make all of the sets and write and direct and edit and produce a movie all on your own.) The level of control in Biller’s newest, The Love Witch, is remarkable; from the mannered performance of its lead actress to the rich interplay of colors in its mise en scène, The Love Witch is designed to evoke an extremely specific period in cinema history and to subtly undermine its ideology through that very faithfulness. Biller plays with the idea of the femme fatale by making her a fool for love and her victims straight fools; early on in the film, someone tells Elaine (Samantha Robinson), “You sound like you’ve been brainwashed by the patriarchy,” not yet realizing that that’s exactly what makes her so dangerous. Unapologetically feminine and wickedly subversive, The Love Witch is a treat for both the eye and the mind. []

Most decent kids’ entertainment blends material for older and younger viewers. But DreamWorks’ CGI movie, Megamind, pushes this dynamic weirdly far, squarely targeting viewers who’ll catch jokes based on the original Donkey Kong, or recognize Marlon Brando from Superman, or Pat Morita from Karate Kid. The tone draws heavily on wryly postmodern, self-aware send-ups like The Venture Bros., and it’s so packed with references familiar to longtime superhero aficionados that smaller viewers may not be sure what they’re seeing, apart from bickering and explosions. There’s nothing wrong with animation aimed at adults, but this may be the first kids’ movie that throws fewer bones to its supposed intended viewers than to their parents. []

When Kara Hayward steals away for a romantic camping adventure with her endearingly awkward 12-year-old suitor (Jared Gilman), she brings along an impractical array of supplies, including a portable record player and a cachet of illustrated books with titles like Shelly And The Secret Universe. ’s charming fantasy feels like an adaptation of one of those books, at least in the world it creates—cloistered, enchanted, and full of hand-drawn wonders, the sort of place that authors lay out in a detailed map before the first chapter. For seven features now, Anderson has created secret universes like the one in Moonrise Kingdom, and invited viewers to immerse themselves in the idealized realm of his own miniaturist obsessions. Yet as tempting as it can be to dismiss them as fussy little art objects or shallow exercises in pastiche, his films aren’t closed off entirely. Real emotions occasionally ripple their pristine surfaces. []

Donald Faison wanders through Next Day Air in a stoned haze as the unlikeliest of catalysts. The baby-faced Scrubs veteran plays a fuckup so incompetent that he can barely hold on to a job where his mom is his boss. Even his smoke-buddy Mos Def has the initiative to steal from his employers and customers, but Faison’s ambitions begin and end with toking as much weed as possible without losing his job. Faison sets Next Day Air’s plot in motion when he accidentally delivers a package containing a small fortune in cocaine to a trio of stick-up kids with more balls than brains: Wood Harris, Mike Epps, and a sleepy thug who spends so much time on the couch dozing that he’s become part of the furniture. Scenting a big payday, these small-timers decide to immediately sell the coke to Epps’ cousin, a paranoid mid-level dealer looking to make one last score before leaving the business for good. But the intended recipient of the package isn’t about to let Faison’s screw-up go unpunished, nor is the hotheaded Hispanic kingpin whose drug shipment has mysteriously gone missing. A very pleasant surprise, Next Day Air is the rare crime comedy that does justice to both sides of the equation. []

To describe Paterson, the new film by Jim Jarmusch, is to risk making it sound both cutesy and condescending. Adam Driver, gangly millennial prince, plays Paterson from Paterson, New Jersey, a bus driver who moonlights as a poet. If the wordplay of that setup doesn’t make you gag (even the casting is a pun), there’s the implied novelty of the premise: Is it really so unusual, the idea that the dude manning the wheel of public transportation could be (gasp!) a creative person? And yet for all the warning flags its log line throws up, Paterson turns out to be something really special: a sublimely mellow comedy about everyday life. And that’s because Jarmusch, that aging ambassador of cool, sincerely respects both the the ordinariness and the artistry of his blue-collar hero. One does not contradict the other. They are intimately related. []

“When the revolution comes, it will be because of this wedding,” says first son Alex Claremont-Diaz (Taylor Zakhar Perez) in the opening minutes of . A nod to a “revolution is coming” is a cliché at this point, vague enough to gesture at pretty much anything. In this case, at least, the vagueness is the point. Alex is referring to the conspicuous consumption before him, but anyone with at least passing knowledge of the story they’re about to witness knows they’re about to watch a gay rom-com, a genre growing in prominence but still relatively rare. Red, White & Royal Blue, ultimately, isn’t revolutionary. It’s more traditional than not—which means, thankfully, that it’s still a lot of fun. []

Jason Schwartzman stars as Max, an oval-faced marvel of misdirected adolescent energy in the fast, exhilarating new comedy Rushmore. Founder and president of just about every extracurricular activity at the exclusive Rushmore Academy—including fencing, dodgeball, beekeeping, and a theater troupe that stages a faithful production of Serpico—Schwartzman is also failing all his classes. His priorities are quickly rearranged when he vies for the affections of a first-grade teacher (Olivia Williams) with a wealthy, clinically depressed man-child (Bill Murray). Since Anderson and Wilson have great respect for hare-brained schemes and wild romantic gestures, Schwartzman is encouraged to mature only insofar as he outgrows his extreme self-obsession, no small feat. Rushmore is a coming-of-age story made by filmmakers who don’t have much use for grown-ups, which is to say that Bill Murray finally gets a chance to deliver a career-defining performance. Murray has always been funny, often in vehicles unworthy of deadpan genius; imagine how unwatchable What About Bob? or The Man Who Knew Too Little would be without him. The hint of genuine pathos he brings to Rushmore tempers Schwartzman’s brash, sometimes off-putting antics, gracing an already great comedy with surprising depth and heart. []

Even in the summer of 2000, Shanghai Noon felt a bit outdated. On multiple levels, it’s a throwback: to the kinds of odd-couple action-comedies that littered the multiplex in the’80s and ’90s, but also to the silly ’60s Westerns that trafficked in broad stereotypes about native people and pioneers. The movie’s schtick is slick and satisfyingly familiar but creaky. Still, that’s where having a great cast helps. Liu brings uncommon poise and dignity to the thankless role of the damsel in distress, while Roger Yuan and Xander Berkeley make suitably cocky villains. There’s even a small, hilariously nutty Walton Goggins turn as the loose cannon in Roy’s gang. Yet what mostly makes Shanghai Noon so easy to rewatch 20 years later is that director Tom Dey lets his leads do their thing. Chan gets to be the overlooked little guy with the big talent, performing dazzling stunts with crack comic timing. And Wilson gets to be the lovable dreamer, who gives us the essence of The Owen Wilson Experience when he survives a near-death experience and then becomes all sappy, saying, “I’ve never noticed what a beautiful melody a creek makes. I’ve never taken the damn time.” []

The world probably doesn’t need another stoner comedy—not with the likes of The Big Lebowski, Dazed And Confused, Harold & Kumar Go To White Castle, and Dude, Where’s My Car? in constant rotation—but it gets one anyway in Gregg Araki’s Smiley Face, which probably connects to the experience of being baked better than any of them. To wit: In one scene, a completely toasted Anna Faris is scarfing down a bowl of corn chips in a stranger’s house when she notices a framed black-and-white picture of an ear of corn. She surmises that the person who took the picture must love the corn that went into those chips, and thus has framed this thing that he loves. That gives her the idea that she should start framing pictures of things that she loves, like lasagna, which of course Garfield loves, so maybe to be “meta,” she should frame a picture of President James Garfield. This is how the stoned mind operates, making brilliant, inspired connections that are usually completely inane. []

In Something’s Gotta Give, Jack Nicholson plays a man who’s worlds apart from Warren Schmidt, but who comes to wear Schmidt’s knowledge for all the world to see. That adds a touch of gravity to Nancy Meyers’ pleasantly but deceptively lightweight film, a romantic comedy that takes a rare tack by leaving its characters different from how it finds them. Nicholson begins the film as a man happy to keep reminders of aging at arm’s length: He’s driving to a romantic Hamptons weekend with girlfriend Amanda Peet, the latest in his string of nubile twentysomethings. But their getaway is interrupted by the arrival of Peet’s playwright mother, Diane Keaton, then by a mild heart attack that leaves him recuperating in the latter’s beach house. The setup is about as obvious as they come, but Meyers steers away from romantic-comedy clichés until she has no other choice. But mostly, it’s just a pleasure to watch Keaton and Nicholson learning new steps in an old dance, stumbling to grab at happiness before it’s too late. []

Spaceballs wasn’t one of Brooks’ great successes, but it’s endured in the shadow of Star Wars as a lone “official” parody version. In retrospect, its comic deconstruction of the most successful movies of all time looks more respectful than Lucas’ own prequels, which ultimately seemed to understand less about the appeal (and pitfalls) of their source material. Certainly, George Lucas had good intentions when he tried to redo his own greatest hits, but as Spaceballs teaches us, good is often very, very dumb. []

Set in Los Angeles, a city where nearly half the population is Hispanic, James L. Brooks’ pleasing dramedy Spanglish grapples with meaty issues that face many people who cross national borders, including the difficulties of finding work, overcoming the language barrier, and assimilating to a new culture. But really, it’s about a dilemma specific to rich Hollywood types: What to do about the help? When a full-time housekeeper/nanny enters the picture, it becomes impossible for employer or employee to think about the arrangement as merely a job, because their lives become entangled in ways that go beyond business. Consequently, the master-servant dynamic can grow increasingly awkward and unsustainable, since there’s more at stake for everyone than merely keeping the house in order. Brooks is known for genteel, intelligent entertainments like Broadcast News, Terms Of Endearment, and As Good As It Gets, and he isn’t the man for seething ethnic tension, but he handles these issues with characteristic sensitivity and good humor. []

Scripted by Andrew Niccol, Sacha Gervasi, and Jeff Nathanson, The Terminal draws its inspiration from the true story of Iranian dissident Merhan Nasseri, who has been living in Paris’ Charles De Gaulle airport since 1988 thanks, at least at first, to a series of political snafus. The film has much softer politics in mind, as it uses JFK as a stage to play out the American immigrant experience in miniature. At first confused, threatened, and hungry—think E.T. in out-of-fashion Eastern European clothing—Tom Hanks becomes resourceful in order to survive, making friends with those who can help him and plugging into the airport economy by returning baggage carts for a quarter a pop. Director Steven Spielberg gives the bulk of the movie over to this upward climb, and even fits love into the picture through Hanks’ makeshift courtship of Catherine Zeta-Jones, a stewardess still in thrall to her latest affair with a married man. Told “America is closed” when he first tries to make his way out of the airport, and continually encouraged to move on and become someone else’s problem by status-quo-minded customs chief Stanley Tucci, Hanks instead finds a little America inside, complete with the opportunity to pursue happiness, though there’s no guarantee that he’ll find it. []

Written by Patrick deWitt and directed by Azazel Jacobs, Terri has Jacob Wysocki playing an overweight teenager who lives with his mentally ill uncle Creed Bratton, and suffers through days at a high school where his classmates honk his man-boobs and tease him mercilessly. And Wysocki doesn’t make it easy on himself, either. He’s a sweet, smart kid, but he’s sullen, and frequently tardy, which doesn’t get the teachers on his side. Plus, he wears pajamas to class. The one person who tries to help is his principal, , who had a rough boyhood himself, and considers counseling the school’s misfits to be a personal crusade. He knows—and Terri knows—what it’s like to stumble through the war zone of adolescence, looking for allies. []

The concept of journalistic balance is premised on the notion that there are two sides to every story, but what happens when one of those sides is wrong? For tobacco lobbyist Aaron Eckhart, the deliciously fatuous hero of Thank You For Smoking, that’s never an issue: “The beauty of argument,” he says with a grin, “is that if you argue correctly, you’re never wrong.” Ideally cast as a smug operator not unlike his character from In The Company Of Men, Eckhart proudly declares himself the face of cigarettes, spinning away on behalf of a lobbying group bankrolled by Big Tobacco. Along with drinking buddies Maria Bello and David Koechner—who represent the alcohol and firearms lobby, respectively—Eckhart styles himself as a “Merchant Of Death” (together, they’re “the M.O.D. Squad”), but public contempt ricochets off him. With the industry facing heavy losses in court rulings and a decline in its core users, Eckhart hatches a plan to boost sales by putting cigarettes into Hollywood movies. Over his ex-wife’s objections, Eckhart takes his impressionable son (Cameron Bright) out to Los Angeles to see what dad does for a living. Meanwhile, a Washington reporter (Katie Holmes) tries to profile Eckhart for a major newspaper, but the two quickly find ways to compromise the story. []

There’s Something About Mary opens with a high-school loser (Ben Stiller) being asked to the prom by dreamy Cameron Diaz after he comes to the aid of her retarded brother. He is unable to realize his dream date because of, in the first in a series of disgusting gags, an unfortunate zipper accident. When the detective (Matt Dillon) he hires to find her 13 years later also falls for her, hilarity ensues. The Farrellys deliver visual and spoken gags at a relentless pace; no subject is taboo in its quest to make the audience laugh and cringe at the same time. Just when you’ve recovered from one scene, another jumps off the screen, without any sense of condescension in the the jokes’ delivery. There’s Something About Mary feels as if the writers, directors, and actors are all enjoying themselves as much as the audience is, and the casting is nearly perfect. Stiller is immensely likable as a pleasant but unfortunate everyman who only wants to find love; Dillon displays a comic panache only hinted at in Singles; and Diaz is the ideal straight woman, unfazed by the buffoonery that surrounds her existence. There’s Something About Mary is one of the funniest movies of its era, but you may need to shower afterwards.

Jim Cummings’ deeply discomfiting comedy Thunder Road takes its title from the majestic opening track of Bruce Springsteen’s breakthrough album, Born To Run, but its spirit recalls the Boss’s throatier cries from the heart and yawls of confused blue-collar emotion. In a terrific opening scene (basically a remake of Cummings’ award-winning 2016 short film of the same title, with one key change), a Texas patrolman named Jimmy Arnaud (Cummings) takes to the front of a church to deliver an improvised eulogy for his mother. He is the only one of three siblings to have made it out to the funeral, though we don’t know why. It’s obvious that he doesn’t want to be there either. His rambling, devolving 10-minute monologue slips from thank-yous and reminisces about his problems with dyslexia and his mother’s love of Bruce Springsteen (specifically “Thunder Road”) into flop sweat and meltdown, breaking into ugly, fully-body crying and finally a bizarre, silent interpretive dance of despair. []

Totally Killer is a film full of great talent, great moments, and an infectious sense of fun, which means that even when it doesn’t quite work, it’s an entertaining balance of slasher tropes and time travel adventure. It’s not necessarily a new slasher classic, but it is the kind of film horror devotees can happily kick back and enjoy on a cozy Friday night in October, and that’s a particular achievement all its own. []

George Clooney plays a man who has perfected a dubious but widely applicable skill in Up In The Air: He fires people. Somewhere along the line, he also offers some advice that makes their dismissals sound like the beginning of a glorious new tomorrow. It’s canned, but it sounds sincere coming from Clooney, and not just because he offers it with an unblinking gaze that suggests utter conviction. He really believes it. Or at the very least, he believes in a life without attachments, in which he drifts from airport lounge to hotel room while racking up an inhuman number of frequent-flier miles and returning to his sparsely appointed Omaha apartment only when need requires. Jason Reitman’s direction nicely translates the seductive appeal of sterile public places while letting the assured performances do much of the work. The film isn’t shy about laying out its themes, but Clooney’s understated work at the center lends them added complexity. What Up In The Air lacks in surprises—apart from an elusive final scene—it compensates for by conveying the pleasures of living from landing to landing, and the terror of floating away. []

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.