The best comedy movies on HBO Max right now

HBO's streaming platform offers plenty of laughs, from Little Shop Of Horrors to The Suicide Squad

If you’re looking for laughs and our overall list of the best HBO Max movies has too many dramas for your taste, The A.V. Club has simplified your search: We’ve rounded up the best and brightest comedy films available on the platform right now. Classics from the likes of MGM, New Line, and 20th Century Studios join the Warner Bros. catalog; from Charlie Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux to James Gunn’s action-comedy The Suicide Squad, this list of titles offers snapshots of comedy gold through the years. Whether you’re logging into HBO Max for an old favorite or looking to discover a new one, here are the comedies guaranteed to keep you entertained.

This list was most recently updated on February 23, 2023.

Following the tradition of bad late-’80s comedies like Vice Versa, Like Father Like Son, and, ahem, 18 Again!—and their slightly improved ’00 counterparts Freaky Friday and 13 Going On 30—17 Again uses Hollywood magic to put an old soul in a younger body. As the film opens, Efron is a star high-school basketball player who leaves the game behind when he finds out his girlfriend is pregnant and commits to her on the spot. Twenty years later, this dynamic young man has morphed into a defeated sad-sack (Matthew Perry) who has squandered his marriage to wife Leslie Mann and alienated himself from his two teenage children. When a janitorial “spirit guide” gives him a chance to revisit his youth and realize the dreams he left behind in high school, Efron instead uses the opportunity to get his family back on track. With plenty of help from a fine supporting cast, including Thomas Lennon as his obscenely wealthy super-nerd chum and Melora Hardin as the school principal, Efron deftly handles the fish-out-of-water hijinks and slips through more icky May-September romantic entanglements than an average season of Friday Night Lights. []

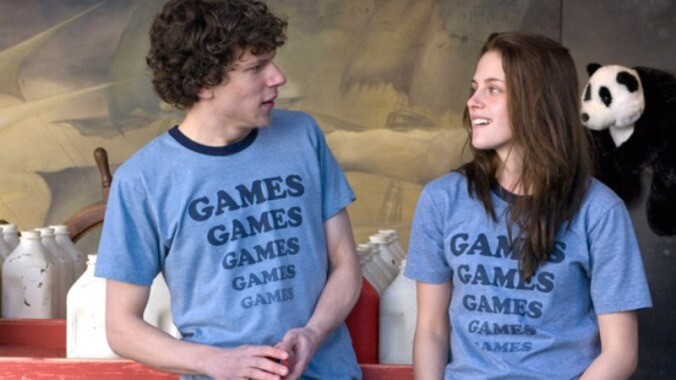

In Adventureland, Jesse Eisenberg stars as a kinder, gentler version of the insufferable faux intellectual he played in The Squid And The Whale, a deep thinker in a superficial ’80s world where artsy pretensions don’t survive a long, boozy, pot-scented season in purgatory working at a second-rate amusement park. Eisenberg’s innocence is nicely matched by the coltishness of suddenly ubiquitous Twilight breakout star Kristen Stewart. Watching Eisenberg fall in love with Stewart is like watching the mating rituals of photogenic wild animals who care about books and interesting films. Greg Mottola’s follow-up to Superbad casts Eisenberg as a virginal recent college graduate who gets a shitty job running games at an amusement park as a way of passing time before his real life begins. At work, Eisenberg falls helplessly in love with a co-worker (Stewart), a brooding, intense young woman stuck in a go-nowhere affair with married man Ryan Reynolds. Mottola digs into the repertory company of Superbad producer Judd Apatow to score juicy supporting turns from Bill Hader, Kristen Wiig, and especially Martin Starr, who steals the film as Eisenberg’s acerbic friend. []

It’s hard to choose the more impressive achievement of Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini’s big-screen adaptation of Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor comics: the assured, casually experimental blend of documentary, animation, and naturalist comedy, or the way Berman and Pulcini assemble 30 years of Pekar stories into one thematically consistent piece, incisively capturing his guiding principle that commoners have as much to say as kings. []

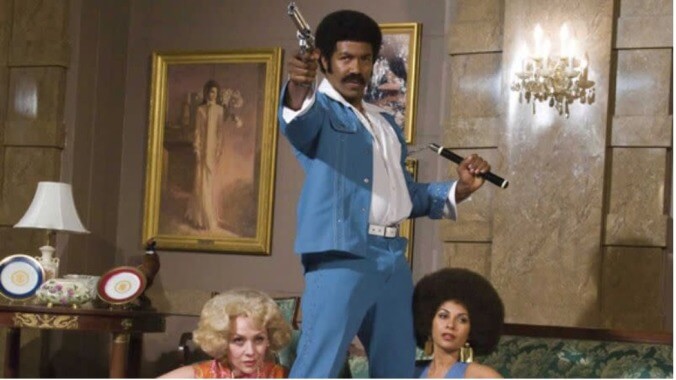

Another blaxploitation parody/homage might have seemed a little redundant after I’m Gonna Git You Sucka and Undercover Brother, but the clever new spoof Black Dynamite justifies its existence with amazing cultural specificity and uncanny attention to detail. Working from a script he co-wrote with star Michael Jai White, director Scott Sanders has created a genre pastiche every bit as loving and meticulous as Far From Heaven or The Good German, though this time it’s in service to a film boom defined by wooden dialogue, terrible acting by models and ex-athletes, and filmmaking that can charitably be called charmingly homemade, or not so generously derided as incompetent. In a potentially star-making performance, accomplished martial artist White stars as the titular badass, an ex-CIA operative who now whiles away his days destroying sparring partners with his devastating moves, making sweet love to an overflowing harem, and generally kicking ass. But when mysterious forces kill his brother, White roars back into action, battling evildoers on an epic quest that takes him from the mean streets of L.A. to Kung Fu Island to expose a conspiracy whose tentacles reach the highest levels of American power. []

Cut and pasted from the texts of five different plays (plus snippets of Holinshed’s Chronicles, the Bard’s main source on English history), Chimes At Midnight puts larger-than-life John Falstaff, Shakespeare’s most popular comic role, center-stage, only to dwarf him with cathedral and castle interiors. Orson Welles made innovative use of low angles in his debut, Citizen Kane, reinventing ceilings as backdrops; here, in his final trip into the corridors of power, they seem so far above as to be unreachable. Even Chimes At Midnight’s brutal, celebrated Battle Of Shrewsbury sequence—a hurricane of medieval violence that has remained a key Hollywood reference point for decades—finds time to cut back to Falstaff, wobbling around in a suit of armor like a lost astronaut roaming the moonscape of history. A big chunk of Welles’ body of work could be divided up into movies about power (e.g. Citizen Kane, Macbeth) and movies about powerlessness (e.g. The Lady From Shanghai, The Trial), and Chimes At Midnight fits squarely into the latter category. []

A Christmas Story got where it is because of TV, and it’s not hard to see why. The movie made its TV debut on HBO in 1985, then slowly made its way toward channels more people had, popping up on WGN and Fox on either Thanksgiving night or the night after Thanksgiving a few times before eventually making its way into the hands of the Ted Turner empire, where it was destined for great things. Even in the ’90s, TV ratings were beginning the long process of splitting into smaller and smaller niches, and networks of all shapes and sizes understood that one of the vital pieces of any year-round ratings puzzle were holiday specials. TNT and TBS bet big on A Christmas Story, showing it more often every year, until arriving at the day-long marathon on TBS that will air again this year beginning Tuesday night. The networks took a good movie that people had responded to and turned it into an event, even as NBC was limiting Wonderful Life airings to one or two per year. A Christmas Story became the de facto American Christmas movie and hasn’t looked back. []

Constance Wu stars as Rachel Chu, a practical NYU economics professor who’s shocked to learn that the man she’s been dating for the past year is basically Singaporean royalty. Hunky boyfriend Nick Young (Henry Golding) isn’t just rich; he’s the 1 percent of the 1 percent. And since he’s set to inherit the family’s real estate empire and expected to marry the right sort of woman to sit by his side, there’s a metric ton of pressure on Rachel’s shoulders when she joins Nick in Singapore for his best friend’s wedding and meets his family for the first time. Nick’s intimidating mother, Eleanor (Michelle Yeoh), immediately disapproves of her son’s choice. And Rachel—who was raised in the U.S. by a hard-working Chinese immigrant single-mom—is treated to a crash course in cultural differences, not just between the rich and the middle class, but also between Asian and Asian-American cultures. There’s a version of this film that holds Nick more accountable for thrusting Rachel into an overwhelming world without much in the way of guidance. Crazy Rich Asians doesn’t take that route. Instead, Nick remains a dashing Prince Charming (Golding more than fits the bill), and the threats to his relationship with Rachel are external rather than internal. There are plenty of heartwarming, tearjerking romantic moments to keep rom-com fans happy, but Crazy Rich Asians is first and foremost the story of Rachel struggling against the complex dynamics of Nick’s insular family. It’s also a surprisingly thoughtful meditation on wealth and womanhood. []

Federico Fellini favorite Marcello Mastroianni stars in Divorce Italian Style as a Sicilian baron undergoing a midlife crisis. He feels smothered by his wife Daniela Rocca, a lightly mustachioed woman with a witchy laugh and a ravenous sexual appetite, and he still sees himself as a desirable catch, able to turn young ladies’ heads with his wealth and good looks. Mastroianni is especially attracted to his teen cousin Stefania Sandrelli, but being Catholic, he can’t do much about it. His best bet is to catch his wife with another man, kill her, and plead “crime of passion.” So he goes looking for a man who might want to sleep with Rocca. That plot description could fit farce or noir, and Divorce Italian Style is a little of both, with the noir elements coming through Mastroianni’s whispered flashback narration and dark fantasies. []

The key statement made by Jim Jarmusch’s 1984 masterpiece Stranger Than Paradise, one which defined and resonated through independent cinema for years afterward, was that American films don’t have to be defined by propulsive stories, or even by dynamic characters. It was achievement enough simply to evoke a small corner of the world as specifically and flavorfully as possible, preferably one that the audience rarely gets a chance to see. In this respect, Jarmusch’s superb 1986 follow-up Down By Law can be described as many things–a minimalist fairytale, a modern twist on ’30s prison dramas, an existential comedy–but it’s memorable first and foremost as a richly textured look at old New Orleans and the enchanted bayou surrounding it. With music and songs by stars John Lurie and Tom Waits, and stark black-and-white photography by the great Robby Müller (Paris, Texas), the film breaks off from the tourists on Bourbon Street and finds inspiration in the city’s decaying underbelly–”a sad and beautiful world,” as Waits neatly poeticizes it. []

For Mary and Paul Bland, the protagonists of Eating Raoul, the world never stops offending. A sexless but happily married couple played by former Warhol star and her frequent on-screen partner Paul Bartel—the film’s director and co-writer with Richard Blackburn—the Blands dream of opening an old-fashioned country restaurant, but can’t seem to get ahead, held back by bills and unexpected unemployment. (Turns out the corner liquor store employing Bartel didn’t need a healthy supply of expensive French wine.) So they’re stuck instead in their tastefully retro apartment in the middle of one of Los Angeles’ most tasteless corners, surrounded by swingers who, gasp, even invite them to loosen up and join their party. But when one violates their home, and attempts to violate Woronov, they kill him, pick his pockets, and hit on an idea: Why not take out an ad in a sleazy local newspaper to attract sexual perverts and repeat the process until they have money enough to get out? After all, who’s going to miss a few swingers anyway? []

Sanding down some of its source material’s sharper edges, Emma remains the epitome of the mid-’90s Miramax period piece; it’s a light, fluffy confection whose liveliness and good humor outweigh its lack of depth. Adapting Jane Austen’s revered novel, screenwriter-director Douglas McGrath takes a spirited approach to the 19th-century English tale of young Emma Woodhouse (Gwyneth Paltrow), who spends a year attempting to play matchmaker for a number of acquaintances, the most prominent being Harriet Smith (Toni Collette), a new friend just starting out in high society. Emma’s efforts to set up Harriet with local minister Mr. Elton (Alan Cumming) help kick-start a roundelay of romantic pairings and partings, which eventually come to include Emma’s own relationships with both Frank Churchill (Ewan McGregor), the coveted son of her governesses’ new husband, and George Knightley (Jeremy Northam), her close family friend. McGrath stages his story with little aesthetic flair, and from today’s perspective, his film’s production design proves far less convincing than that of . Still, the director’s fondness for extended takes allows Austen’s memorable characters, and his cast’s uniformly compelling performances, to command center stage, and his script effectively channels the novel’s atmosphere of amorous anticipation, longing, and confusion. []

It should come as no great surprise that Wes Anderson is a. They share a sensibility, don’t they? Call it an appreciation of the finer things, coupled with a neat and pleasing organizational sense. Anderson, director of live-action movies with the visual imagination of cartoons and cartoons with the soul-deep neurosis of live action, has a style so singular it can be identified from a single frame plucked from the celluloid reels he still shoots on. Yet there is an antecedent for his beloved approach, and one big influence has to be the storied periodical he’s said to have consumed religiously in college, from whose pages he might have drawn a sense of humor at once refined and playful, an affinity for symmetries and pastels, and a voracious appetite for literary pleasures. Were Wes Anderson an airline, The New Yorker would be its in-flight magazine. Of The Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun, henceforth referred to by the first three words of its title, is Anderson’s love letter to that 96-year-old highlight of mailboxes and waiting rooms—and by extension, to the nearly century of art, writing, and reporting contained within… []

Wes Anderson doesn’t so much direct movies as build them from scratch, brick by colorful brick. He’s an architect of whimsy, his brain an overstuffed filing cabinet of elaborate blueprints. To watch one of his comedies—and they’re all comedies, from the boisterous to the magical —is to be ushered into a new world, custom designed from top to bottom. Anderson’s latest invention, , may be his most meticulously realized, beginning with the towering, fictional building for which it’s named. From the outside, this luxury establishment—situated in a scenic corner of an imaginary Eastern European country—resembles nothing so much as a giant, frosted birthday cake, delectable enough to devour. On the inside, it’s a museum of invented history, every room dressed with so much that it could inspire a whole series of spinoffs. Were the merit of the man’s films determined solely by the amount of bric-a-brac they contain, this new one would surely rank first in his illustrious filmography. To some, The Grand Budapest Hotel probably will look like a career pinnacle, if for no other reason than it crams all of its creator’s signature moves and interests into one zippy package. []

For the first half-hour, Gremlins plays more like a Spielberg knock-off than a movie made by , a director at that point best known for his work on The Howling. Billy Peltzer (Zach Galligan, whose main job is to be nice and act well with puppets) is just a regular guy, living with his parents, working at the bank, feeling too nervous to ask the girl of his dreams out on a date. He lives in Kingston Falls, an idyllic, Bedford Falls-inspired small town. (The movie makes this debt explicit when it shows Billy’s mom watching It’s A Wonderful Life in the kitchen; she’s crying, but only because she’s cutting onions, which is probably a tip-off.) His life is the sort of pleasant but not quite satisfying existence that serves as the starting point for so many modern comedies. Billy is in a rut, content to draw sketches and hang out with the neighborhood kids, but not quite ready to make the step into real adulthood. Galligan seems just a little old for the part, too, like he’s wearing clothes that he grew out of a few months ago. When his dad (Hoyt Axton) brings Gizmo home, it’s nice, but sort of random. Is he so out of touch with his son’s life that the best gift he can think of is a bizarre animal semi-stolen from an old Chinese man’s junk shop? Billy starts bonding with the Mogwai faster than you can say “Phone home,” which is adorable, but again, slightly off. Where is this going? Who does Gizmo need to call? []

Like Spielberg’s Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom, Gremlins caused some furor upon its release, and its violence helped lead to the creation of the PG-13 rating. But the film’s edge doesn’t come from gore so much as from willingness to follow its premise to its destructive conclusion. Even better, director Joe Dante’s 1990 sequel Gremlins 2: The New Batch, also available in a fleshed-out new DVD, ignores the edge and jumps right over it. Moving the action (and stars Galligan and Phoebe Cates) to a state-of-the-art office building run by tycoon John Glover, Gremlins 2 begins like a conventional sequel. After fate brings him to a genetics lab located in Glover’s building, Gizmo reunites with Galligan shortly before their monstrous problems predictably begin anew. The predictability soon disappears: Less than an hour in, film critic Leonard Maltin shows up to deliver a review of the original Gremlins, a vicious pan cut short by his death at the creatures’ hands. It only gets wilder from there. Given full freedom by the sequel-hungry Warner Bros., Dante and screenwriter Charlie Haas take advantage of the opportunity, turning in a film that has more in common with one of the studio’s golden-age cartoons than with a live-action feature. A cameo from Hulk Hogan, a brainy gremlin voiced by Tony Randall, and a full-scale musical number all appear before Dante wraps up one of the strangest films ever released by a major studio. By that point, the director has done the original Gremlins one better: Instead of a film with a subversive streak, he’s made a puckish act of subversion with a streak of film. []

Richard Lester kicks off A Hard Day’s Night at full speed—no studio logo, no establishing shots, just the crash of the title’s song opening chord and three moptops (Paul turns up later) running frantically toward the camera, pursued by rabid fans. Thing is, though, the opening conveys a feeling of liberation that the Beatles didn’t actually possess, as A Hard Day’s Night will go on to puckishly demonstrate. The Fab Four are smiling broadly as they make their mad dash for the Liverpool train station in the opening sequence, as if they’re having the time of their lives, but it’s significant that the screenplay they commissioned from Alun Owen is almost entirely about how trapped they feel, just a few months into Beatlemania (a term that was coined in October 1963—shooting started in March 1964). Structurally, A Hard Day’s Night builds toward a climactic television performance, depicting what’s ostensibly a typical day in the life of the Beatles. This mostly involves efforts to elude their manager (a fictional one, here, played by Norman Rossington), who’d prefer to see them locked down in a hotel room answering armfuls of fan mail, and have a bit of fun. In the film’s most iconic sequence, the lads sneak out a fire-escape door as they’re being shuttled back to the room following a rehearsal, cavorting around a field accompanied by the effervescent “Can’t Buy Me Love.” Lester sometimes shoots them in fast motion, sometimes in a flurry of quick cuts, sometimes from a great height—whatever will best capture the giddiness of having temporarily slipped away from the straitjacket of their unprecedented fame. At the same time, though, A Hard Day’s Night is careful not to make the Beatles seem ungrateful; there’s no discussion, for example, of how little the band came to enjoy performing live (to the point where they eventually gave it up completely), due to their inability to hear themselves over the noise. []

The Chicagoans at Rob’s (John Cusack) store, Championship Vinyl, are “professional appreciator”s from afar who can barely hold it together in conversation with rising singer-songwriter Marie De Salle (Lisa Bonet). It’s a much more grown-up male adolescent fantasy (i.e. Rob winds up having a one-night stand with Marie) where the specters of age, responsibility, and purpose are always hovering around while only occasionally impeding on Rob’s daytime routine of listening to music and rattling off personal top five lists, or his off-hours regimen of listening to music and rattling off personal top five lists. High Fidelity is a film colored by a love of music, but it’s also about love love, the complexities of romantic relationships and the path toward becoming a better, fuller person. []

David Lean is best known for his epic late-period historical dramas exploring the psychological contradictions of outsized figures, like Lawrence Of Arabia, The Bridge On The River Kwai, and Doctor Zhivago. But his directorial career began with eminently British literary adaptations filmed on a smaller scale—Noël Coward’s This Happy Breed, Brief Encounter,and Blithe Spirit; Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist and Great Expectations; and an adaptation of Harold Brighouse’s perennially popular theatrical comedy Hobson’s Choice. Released in 1954, Hobson’s Choice is the last of Lean’s black-and-white films; the following year, he directed Summertime (also originally a play) in glorious Technicolor, and then the huge spectacles began. As befits a film that marks this transition, Hobson’s Choice embodies the very best of the intimate Lean, while anticipating the startling clarity of vision he would later bring to the North African desert and the Russian steppes. []

House Party premiered at the 1990 Sundance Film Festival, part of a pack of extremely promising debut features that also included Whit Stillman’s , Hal Hartley’s , and Wendell B. Harris Jr.’s , which took home the top prize. But House Party was different: It didn’t aim for the arthouse crowd, but for multiplex audiences. The fact that it became a very profitable hit, spawning sequels and imitators, didn’t have much to do with the fact that it had picked up awards at Sundance for writer-director Reginald Hudlin and cinematographer Peter Deming, later known for his work with David Lynch. (Coincidentally, Lynch’s own debut, , gets name-checked.) With the exception of a homophobic tangent—which the movie’s been rightly called out on since it first hit Park City—it’s as fun as unapologetic teensploitation gets. Hudlin didn’t subvert or reinvent a form that had been around since enterprising drive-in producers figured out they could cash in on rock ’n’ roll. He just did it better: a sort of clean-cut early ’60s movie for the R-rated early ’90s, right down to the shaggy-dog plot, the bully villains, and the cast of high schoolers who all look like they’re in their mid-to-late 20s. []

I Married A Witch stars Veronica Lake as Jennifer, a witch with an origin story more appropriate for a horror film: She and her father (Cecil Kellaway) were both burned to ash during the Salem witch trials. In revenge, the still-sentient pair places a spell on the family of the man who exposed them. Hundreds of years later, Jennifer and her father return to corporeal form to further torment descendant Wallace Wooley (Frederic March). Specifically, she aims to help along her curse that dooms every Wooley male to marry the wrong woman. Wallace, a candidate for governor, is already well on his way, engaged to Estelle (Susan Hayward), but Jennifer endeavors to seduce and abandon him anyway. She only further complicates matters by actually developing feelings for her prey, much to the chagrin of her vengeful father. Various transmogrifications, revelations, and general shenanigans ensue. I Married A Witch is fairly heavy on incident for a 77-minute movie; it has the bones of a screwball comedy, but with a more whimsical soul. []

Howard Ashman and Alan Menken’s 1986 musical Little Shop Of Horrors eventually ran on Broadway, but arrived there via an unusually long path: It began life as a 1960 Roger Corman horror-comedy, which Ashman and Menken adapted into a stage musical in the early ’80s. The show played off-off-Broadway, then off-Broadway, then in movie theaters as a film adaptation written by Ashman and directed by Frank Oz (a shorter-lived Broadway revival followed years later). The Oz film remains one of the very best modern stage-to-screen transitions, and easily the best to involve a man-eating plant. As Seymour Krelborn (Rick Moranis) explains in the flashback song “Da-Doo,” he comes upon this “strange and interesting plant” during a stroll through the city streets coinciding with a solar eclipse. The plant helps bring customers into the Skid Row flower shop where Seymour and his crush Audrey (Ellen Greene, who originated the role in the off-Broadway play) both work, but Seymour quickly realizes the flytrap-like plant, which he christens Audrey II, wilts unless it feeds on human blood. Complications ensue, as they often do when human blood is made a vital ingredient in a diet. []

Though still potent, the shocking-at-the-time 1992 satire/mockumentary Man Bites Dog, from Belgian co-directors and stars Rémy Belvaux, André Bonzel, and Benoît Poelvoorde, may have slightly less impact now, given the similar and even nastier provocations that followed. But its vérité treatment of a preening serial killer cagily predicts the current era of reality TV, where hollow fame-seekers get their 15 minutes and the camera eggs them on, turning their lives into a sick form of performance art. While its title is taken from journalism—referring to news favoring the sensational (“man bites dog”) over the everyday (“dog bites man”)—Man Bites Dog isn’t really a comment on media so much as filmmaking itself, and the way it forces moral compromises from people both behind the camera and in front of the screen. It’s a sick piece of work—I felt like a heel for watching it, yet I couldn’t look away, either. []

A title card at the beginning of Whit Stillman’s debut feature, Metropolitan, identifies the time period merely as “not so long ago.” At the time—the film was originally released in 1990—Stillman was looking back roughly 20 years, to the early 1970s; of course, many more years have passed since then. It doesn’t really matter, though, as Metropolitan has always felt like a movie that exists in a strange, insular little bubble of its own, utterly divorced from the personal experience of virtually anyone who watches it. The film’s enduring appeal lies in its sardonic yet warmly affectionate portrait of New York’s debutante-ball subculture, which has rarely appeared onscreen before or since. Few will identify with the ludicrously wealthy characters, who speak in perpetual bon mots and are virtually never seen in anything but formalwear, but their stubborn refusal to evolve with the culture—forever sounding as if they’re in one of the Jane Austen novels they so earnestly discuss—is part of their charm. Shot on a shoestring, Metropolitan doesn’t actually show the balls themselves, and it doesn’t really have a narrative to speak of. Mostly, it’s a series of hilariously mannered conversations at the ball’s after-parties, involving a group of Upper East Siders. Some minor intrigue derives from the presence of Stillman surrogate Tom Townsend (Edward Clements), an Upper West Side resident who’s adopted by the gang when he and they try to hail the same cab. Tom is probably at least in the 85th percentile financially himself, but he’s a pauper compared to the UHB crowd, and he also fancies himself to be vehemently opposed to the self-satisfied ostentation of high society. Nonetheless, he keeps coming around all week, and slowly begins to realize that Audrey (Carolyn Farina), the most sensitive and literary-minded of the debs, has developed feelings for him. []

After setting off to a small resort, Jacques Tati wreaks havoc simply by attempting to enjoy himself. A flat tire, for instance, involves him in a somber funeral which he’s too polite to leave; an invitation to tennis makes a mockery of the game. Holiday is packed with more gags than a Naked Gun film, but Tati, as always, assumes a slow pace, not so much to allow viewers to savor his craft, but because his jokes need time to unfold. []

An assured combination of suspense and pitch-black comedy, Monsieur Verdoux proceeds as a series of sketches, mixing light slapstick with snappier dialogue than anything Charlie Chaplin had attempted before. Both the humor and the tension stem from Chaplin’s attempts to convince his victims to empty their bank accounts before he snuffs them, and the women’s attempts to get their dreamboat to be more like a regular husband who stays home and helps around the house. Chaplin’s antihero is a sweet-talker, adopting multiple personas to explain to his ladies why he’s only around for a few days every month. Monsieur Verdoux emphasizes both his diligence—he counts francs rapidly, like the banker he used to be before the economy tanked—and how hard it is for even the most confident, careful person to commit murder. The comedic core of the movie lies in the scenes between Chaplin and Martha Raye, who plays a quick-tempered, overly affectionate lottery winner, described by a friend as so lucky that, “If you slipped on a banana peel with your neck out of joint, the fall would straighten it.” She’s the unkillable object in the path of Chaplin’s ruthless rogue, and his elaborate, ill-fated schemes to end her life are where Chaplin the silent star shows his still-formidable flair for building visual gags within a still frame. []

“Obviously something terrible had happened to Andre,” Wallace Shawn concludes after hearing reports about an old friend’s strange behavior toward the beginning of My Dinner With Andre. Once an acclaimed director of experimental theater, Andre Gregory spent years globetrotting and returned a changed man, someone who might go on about talking to the trees, or be seen weeping on street corners. As the film opens, Shawn has reluctantly agreed to catch up with him over dinner. Joining him at an upscale, just slightly forbidding restaurant, Shawn finds Gregory relentlessly upbeat, at least on the surface, and listens to his tales of super-fringe acting workshops, travels in the Sahara, a piece of performance art that involved being buried alive, and other strange adventures. After listening politely, Shawn replies. And that, in short, is My Dinner With Andre, an arthouse hit in 1981 built around a conversation between old friends and collaborators playing themselves, directed with dining-room intimacy by Louis Malle. []

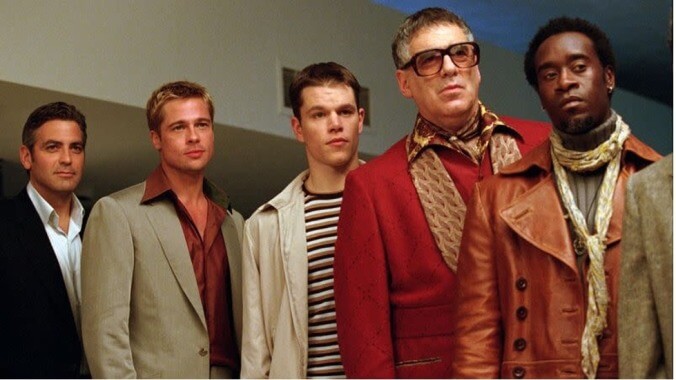

Ocean’s Eleven, a shamelessly commercial, superhunk-packed, briskly enjoyable caper comedy that’s ostensibly a remake of the lumbering 1960 Rat Pack vehicle of the same name. The prospect of a middling Rat Pack showcase being remade with 2001's top pretty boys might initially seem as appealing as a re-imagining of Clambake starring Ricky Martin, but Eleven is more a rehash of Out Of Sight, with which it shares cast, crew, and a nearly identical tone, look, and sensibility. This time, [George Clooney’s] act of grand larceny involves conspiring with fellow slickster Brad Pitt to rob silky-smooth casino owner Andy Garcia in revenge for Garcia’s theft of Clooney’s long-suffering ex-wife (Julia Roberts). Ocean’s Eleven boasts an oily, secondhand charm that’s transparent but strangely endearing. With his Oscar-winning direction of the similarly star-studded Traffic, managed a remarkable balance between style and substance. In Ocean’s Eleven, style delivers substance a Dream Team-style pounding, but the results are so breezily entertaining, it’s futile to resist. []

Deep into Ocean’s 13, the second sequel to the 2001 remake of the 1960 Rat Pack classic Ocean’s 11, there’s a line about how a good con man never repeats a gag. It’s delivered as a throwaway piece of dialogue, but it quietly acknowledges that what good con men can’t get away with, good directors sometimes can. Rebounding from the frothy, bloodless Euro jaunt Ocean’s 12, 13 returns Steven Soderbergh and crew to Las Vegas for a film that isn’t exactly a remake of their first Ocean’s adventure, but isn’t exactly not, either. It doesn’t matter. Ocean’s 11's easy chemistry and effortless style return alongside the let’s-take-down-a-casino plot. In this case, the target is the gorgeous—and fictional—Bank Casino, a spiraling, faintly Asian-themed high-rise run by Al Pacino and his scantily clad aide de camp Ellen Barkin. Having sent Elliott Gould into a coma after cheating him out of his rightful stake in the casino, Pacino rouses the ire of Clooney and his crew, who conspire to take him and his elaborately defended gambling palace down. The pleasure here, as before, comes from watching skilled professionals team up for a job well done. []

Robert Altman’s adaptation of Michael Tolkin’s The Player—a novel that eviscerates ’80s Hollywood—begins with a lengthy joke that only cinema could make. As a studio security chief (Fred Ward) bitterly complains about the era’s ADD aesthetic (“All this cut, cut, cut,” he grumbles, blissfully unaware that Michael Bay lurks in his future) and raves about the opening of Touch Of Evil, Altman and cinematographer Jean Lépine execute a ludicrously complex seven-minute shot that wanders all over the lot, even peeking through several windows at pitch meetings in progress. Many of The Player’s major players are introduced over the course of this sequence, and there are some magnificent jokes, including Buck Henry’s pitch for The Graduate: Part 2 (or maybe The Post-Graduate) and Alan Rudolph describing a project as “politely political, but with a heart, you know, in the right place.” (That Rudolph hasn’t been in a film since 2002 makes the latter sting a bit more today.) Still, the main gag is the shot itself, which seeks to impress even as it pokes fun at its own ambition. []

has the bright, alluring sheen of a pop confection. The paint-swatch spectrums of pink and blue—powder to electric neon, baby to deep navy—that dominate its color palette are both soothing to the eyes and in step with Instagram trends. Its soundtrack, packed with 21st-century bubblegum pop, imparts a similar sweetness. The title character wears fuzzy floral sweaters and sucks on red licorice, and every shade of girly, from kawaii to rococo, splashes across the screen at some point. Then there’s the cast, which is full of reassuringly familiar faces, from Adam Brody and Christopher Mintz-Plasse to Laverne Cox and Alison Brie. But the hard-candy shell that coats the film conceals a razor blade, ready to cleave the tongues of those entitled enough to chomp down without letting it melt in their mouths first.In fact, the primary target of this feature debut from one-time showrunner Emerald Fennell is entitlement—specifically, the idea that a man’s potential is worth more than a woman’s well-being. Fennell’s script for Promising Young Woman quakes with a fury toward the Brock Turners of the world; it tracks the long-term consequences of a campus sexual assault that was dismissed and quickly forgotten by both the victim’s friends and university officials. But Cassandra (Carey Mulligan) remembers. Radicalized by the event, she drops out of medical school and reorganizes her life around getting revenge on all those who allowed this frat-boy rapist to walk free—as well as any man who thinks that “blackout drunk” is synonymous with “sexually available.” []

A coming-of-age film that turns Tom Cruise’s high-school senior into an accidental pimp after he nervously hires a call girl (Rebecca De Mornay), Risky Business is partly about how teens grow up, discover desire, and move past the little-kid images that line their parents’ homes. But the “business” half of the title is just as important. Forced to embrace his role as a panderer after wrecking his dad’s Porsche, Cruise winds up looking at capitalism at its rawest as he joins De Mornay in the “shameless pursuit of material gratification.” But eventually, the business gets the better of him, and Cruise is troubled by the suspicion that his relationship with De Mornay might mean nothing more to her than a dollar amount, since she’s so adept at putting prices on everything else. Risky Business found its audience as part of a wave of teen comedies, but Cruise’s character has more in common with Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate than any of the Porky’s horndogs. As the film progresses, he clearly realizes his soul is at stake. If audiences in that material-world decade paid attention, they probably saw a bit of themselves up there. []

Over the course of his career, Peter O’Toole has specialized in larger-than-life characters, magnetic icons who can inspire intense devotion solely through the force of charisma. O’Toole puts this skill to good use in films like Lawrence Of Arabia, The Stunt Man, My Favorite Year, and 1972's The Ruling Class, which gave him three juicy roles in one. Adapted by Peter Barnes from his play, the film casts O’Toole as the 14th Earl Of Gurney, a sweetly deluded paranoid schizophrenic convinced he’s Jesus Christ. Released from a mental hospital following his father’s suicide, O’Toole inherits his father’s lofty title. This troubles his parasitic family and social circle, even Bishop Alastair Sim, who, like O’Toole’s family, is far more comfortable with religious dogma than with Christ’s ideals and values. Desperate for a new, more stable heir, O’Toole’s family attempts to both marry him off and cure him, which backfires when he ceases to think he’s Jesus and begins to view himself as Jack The Ripper. The central joke of Class is that Jack The Ripper can navigate the corridors of power far more smoothly than a beatific Christ figure, and it’s a tribute to Barnes’ script that Class never becomes a one-joke movie, even over the course of 154 minutes. At once a visionary work of provocation and a throwback to an era of stagy, acidic farces populated by sharp-tongued butlers and scheming women, Class uses its theatrical conventions as the platform for an attack on social inequity informed equally by the witty bon mots of Oscar Wilde and the transgressive satire of Terry Southern. []

Singin’ In The Rain defies an auteurist reading. As the film’s star, co-director, and co-choreographer, Gene Kelly would seem like a likely candidate for authorship, but the fact that Kelly shares the last two roles with Stanley Donen reveals the film’s collaborative nature. Similarly, songwriter-turned-producer Arthur Freed could rightly be singled out for his part in its creation, since he came up with its concept of a film that would showcase the songs he’d co-written with Nacio Herb Brown. Finally, screenwriters Betty Comden and Adolph Green can claim much of the credit for Singin’ In The Rain’s success, since they turned a mercenary assignment into an enduring work of art. Ultimately, however, as the audio commentary for the double-disc Singin’ DVD suggests, the film represented a triumph of the studio system rather than the genius of a single powerful vision. Faced with the unenviable task of building a movie around Brown and Freed’s dated songs, Comden and Green hit upon the idea of making the film a nostalgic period piece, a move that allowed them to gently send up the songs’ Tin Pan Alley corniness while reveling in their simple power. Set during film’s awkward transition from silence to sound, Singin’ stars Kelly as a vaudevillian turned movie star whose successful series of films with Jean Hagen seems doomed to end with the arrival of sound; Hagen’s abrasive, squeaky voice suddenly becomes a problem when audiences demand to hear as well as see their idols. Caught in the angry tide of shifting public tastes, the studio behind Kelly and Hagen’s latest film decides to make it a sound picture and then a musical, and fresh-faced ingenue Debbie Reynolds is enlisted to overdub Hagen’s lines. Escapism raised to the level of art, Singin’ In The Rain inventively satirizes the illusions of the filmmaking process while celebrating their life-affirming joy. []

David Ayer’s widely panned often felt like it was trying to give DC its own , complete with mismatched scumbag cavalry and classic-rock needle drops. So it’s fitting that the standalone sequel, , should fall to James Gunn, actual writer and director of the Guardians films, who signed on after crosstown rival Marvel (temporarily) following some unearthed tweets. It’s not so surprising that Gunn redeems the floundering franchise with a gory and uproariously funny R-rated follow-up that makes good on the promise of its premise. Margot Robbie’s Harley Quinn is among a handful of old characters reunited; the sprawling ensemble of new characters are played by Idris Elba, John Cena, Daniela Melchior, David Dastmalchian, Sylvester Stallone, and many more. Fair warning: No reformed supervillain is safe in a comic-book movie this gleefully fatalistic.

“Caught in a storm,” reads the SOS note, bobbing in a sea of perfect blue. On an island too small for one man, one man (Paul Dano, in a Robinson Crusoe beard) tightens a noose around his neck. But he soon has company, washed in by the waves: a man with pallid skin, unblinking eyes, and a mouth frozen in a perpetual grimace. Five minutes is about all it takes for Swiss Army Man to establish its premise, its characters, its single setting. It’s also the amount of time the movie needs to announce itself as the bugfuck American comedy of the year. That lifeless body on the beach bears the unmistakable appearance of Harry Potter himself, Daniel Radcliffe. And before long, the music rises, the opening credits dramatically roll, and suicidal survivor Hank (Dano) is riding his new friend across the water like a jet ski, propelled by his posthumous flatulence. As meet-cutes go, it’s memorable. []

When Ernst Lubitsch borrowed the title for his comedy To Be Or Not To Be from Shakespeare’s most famous tragedy, he couldn’t know how grimly apropos that choice would become. The film was already grappling with unusually weighty subject matter: Opening commercially in March 1942, less than a year after America entered World War II, it dares to poke fun at Hitler and the Nazi regime, and in a way that’s arguably more barbed than Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator. But it also turned out to be the final film made by its female lead, Carole Lombard, who died in a plane crash seven weeks before its release. That’s a somber legacy for a gag machine, even one as serious-minded as this. Contemporary reviews reportedly praised Lombard to the skies, but sniffed that the rest of the movie was in regrettably poor taste. Only with the distance of many years were people finally able to recognize it as a classic.

If you were trying to find a consensus pick for the best romantic comedy of all time, 1989’s When Harry Met Sally would definitely be a huge part of the conversation, if not just the clear-cut winner. It’s the rom-com that forever changed the nature of rom-coms, and you can find traces of When Harry Met Sally’s DNA in virtually every romantic comedy that’s been made since. A funny but pessimistic male lead paired with a neurotic but optimistic female one? Check. Quirky supporting characters who have a subplot about falling in love with each other? Check. A climax that ends with someone running through the streets in order to confess their love? Check. Along with the commercial success of 1990’s Pretty Woman, When Harry Met Sally helped kick off the romantic comedy renaissance of the 1990s. And it launched the rom-com career of one of the genre’s most important contributors, Nora Ephron. []

Though his script for The Killing Fields was nominated for an Academy Award, actor-turned-filmmaker Bruce Robinson is probably best known for 1987's Withnail And I, a cultishly adored comedy recently released on DVD alongside his less-loved follow-up, 1989's How To Get Ahead In Advertising. Loosely based on Robinson’s experiences as a struggling actor in ‘60s London, Withnail stars Paul McGann and Richard E. Grant as chronically unemployed, on-the-dole London thespians wasting away the waning days of the ‘60s in a drunken, speed-addled haze. []

Characters reminisce about the ’90s, wear Pixies T-shirts, and maintain collections of hand-painted action figures in Young Adult, all in line with what viewers might expect from a film that reunites ’s writer and director, Diablo Cody and . What’s different this time around? They’re on the sidelines, gazing with bewilderment, dislike, and/or awe at their heroine, played by Charlize Theron as the type of girl who once upon a time walked all over them. Though her character’s high-school glory days are almost two decades behind her, she’s dredged them up with an unstable determination that attests to the years of disappointment that followed them. It’s an empathetic but bravely brittle portrait of an aging queen bee that showcases a nuanced performance from Theron as a woman too used to being admired to admit how lonely and desperate she’s become. []

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.