The best comics of 2019 so far

An ancient alligator god. A living building. A doomed architect. The subjects of the best comics released in 2019 so far are an eclectic mix, and these stories highlight the stylistic range of the medium with drastically different visual and narrative perspectives. From poignant graphic memoirs to sensational genre tales, these comic-book series and graphic novels find exciting ways to explore the dynamic between images and text. Whether they are spotlighting forgotten sports stars, pitting assassins against each other, or recounting the pain of adolescent heartbreak, these creators take readers on engrossing journeys with their remarkable craft and passionate artistic visions.

Assassin Nation (Skybound/Image)

With four of five issues out so far this year, Kyle Starks and Erica Henderson’s Assassin Nation has been a hilarious team adventure comic. Both creators have serious comedic chops: Henderson might be best known for her work on Jughead and The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl, and Starks has written dozens of Rick And Morty comics, as well as Mars Attacks books. Assassin Nation is a surreal character-driven story populated almost completely by mercenaries and hit men who have been hired to protect one of their own. Comparisons to Deadpool are justified, but there’s also elements movies like Smokin’ Aces—if it were in on the joke. As the name implies, there is a lot of assassinating going on. The gunplay is bombastic and overblown, but there is a very real threat of character death for a gene that often waves away concerns about permanent harm. What drives the book forward are the layers of backstory and history that are revealed slowly, skills and idiosyncrasies coming up after it seems characters have revealed all their secrets. It’s fascinating to experience a large group of two-dimensional characters narrowed down and given depth and weight, and this creative team is knocking it out of the park. [Caitlin Rosberg]

Baseball Epic (Coffee House Press)

The dead-ball era, which spanned from around 1900 to around the 1919 season, when Babe Ruth showed everyone he could really slug, is perhaps the least written about period of baseball’s history. Jason Novak, with Baseball Epic, sought to begin the process of correcting this oversight. The book is made up of more than 100 one-paragraph, handwritten biographies of the players who defined the era, each accompanied by a simple, wobbly black-and-white drawing of the player. The stories he tells of their lives are often whimsical, tragic, and unrelated to their playing careers. He notes that Jim Shaw, for example, “married a nurse he met in the hospital after accidentally shooting himself while hunting rabbits.” The real work of the book is drawing attention to the black, Cuban, and Native American players who played baseball despite horrible racism. This includes Jimmy Claxton, who, in 1916, became the first Black man to play in a white baseball league “by registering as an ‘American Indian’ with the Oakland Oaks, but was booted when a spectator in the bleachers recognized him as a Black man.” Novak’s handles their stories with care and Baseball Epic is a wonderful entrant because of it. [Bradley Babendir]

BTTM FDRS (Fantagraphics)

Buildings are architectural organisms, full of complex systems that work in tandem to provide shelter, air, water, and waste disposal for tenants. Ezra Claytan Daniels and Ben Passmore’s BTTM FDRS takes this idea and mutates it through a grotesque horror lens, creating a haunted house story that speaks to pressing issues of gentrification and the exploitation and ejection of marginalized people in the development process. Set in a giant, windowless concrete cube in the Bottomyards—a fictional neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side that has recently become a haven to hip young artists—BTTM FDRS addresses the history of racist practices in urban housing while delivering a steady stream of weird, unsettling situations that eventually turn deadly. Passmore’s animated art style evokes the look of ’90s cartoons like Doug and Hey Arnold!, bringing an undercurrent of humor to the visuals even when they depict some very dark material. A high-intensity color palette adds an extra pop to the linework, and Passmore composes some very striking images, like a splash page of a toilet overflowing with bright red viscera. The book only gets weirder from there, and the creative team aims to disturb by bringing an inorganic structure to life. [Oliver Sava]

Die (Image)

As teenagers, a group of friends were mystically pulled into a table-top RPG, where they endured life-altering trauma before eventually escaping. Nearly 30 years later, they’re pulled back into this deadly world to stop an old friend gone mad. Written by Kieron Gillen with art by Stephanie Hans and letterer Clayton Cowles, Die is concisely described as “goth Jumanji,” with Hans’ moody digital painting taking center stage as she builds an immersive fantasy world. Gillen, Hans, and Cowles previously worked together on books like Journey Into Mystery and The Wicked + The Divine, and the tight execution of every aspect of Die indicates a high level of collaboration among the team. Gillen gives Hans a story that pushes her design skills and character acting, and she does stunning work with colors to heighten the dreamlike atmosphere, which can turn into a nightmare at any given moment. The J.R.R. Tolkien-centric Die #3 marks an important shift for the series, breaking from the larger narrative to tell a standalone story about the terror of war and how it shaped Tolkien’s fantasy writing. It establishes the creative team’s eagerness to explore tangents that illuminate larger themes, and both the fantasy genre and table-top gaming provide a wealth of storytelling opportunities for the future. [Oliver Sava]

Kid Gloves (First Second)

Lucy Knisley has a well-earned reputation for emotionally evocative, introspective, and intimate autobiographical work. She made her name making comics that sometimes read more like journals than novels. With both Kid Gloves and the previous Something New, she’s begun incorporating background information and science lessons into her books, interspersing things she learned while going through a major life event along with the details of her direct experience. In Kid Gloves, which tells the story of giving birth to her first child, Knisley has carefully included information about maternal mortality rates, tracing industry-wide trends and peeling back layers of uncomfortable history to remind people of the larger context in which her child was born. Her art has become more refined and ambitious, eliciting specific feelings and reactions alongside telling a true story. As with a lot of her previous work, Kid Gloves provides insight not only for people who are about to embark on the same journey, but a sense of belonging for those who have already walked that path, and important points of reference for those who never will. Motherhood and childbirth are far from a universal experience, but Knisley’s book is an important and particularly timely reminder that they are vital. [Caitlin Rosberg]

Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me (First Second)

Writer Mariko Tamaki and artist Rosemary Valero-O’Connell have crafted something masterful in Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me, a YA story as sweet and brutal as teenagers can be. It’s not quite a romance and not just a coming-of-age story told from the perspective of protagonist Freddy, who is sometimes sort of dating Laura Dean. The relationships in Laura Dean are layered and complicated and sometimes painful, and the whole book is rooted in the reality of just how difficult it can be to be a teenager, in love or not. Tamaki is no stranger to this kind of storytelling, and it’s easy to trace the parallels between her award-winning This One Summer and Laura Dean. Valero-O’Connell brings an incredible sense of place and personality to Laura Dean; the characters are designed so distinctly and completely that their personalities are clear from the jump, and her skill with using panel size and crowded spaces make Laura Dean that much more emotive and visceral. The limited color palette in grayscale with a soft shade of pink help to highlight Valero-O’Connell’s deft, gentle hand and the bittersweetness of teenage love. [Caitlin Rosberg]

Middlewest (Image)

Written by SKottie Young with art by Jorge Corona, Middlewest is the story of boy driven away from home by his father’s anger and his family’s legacy, struggling to understand his role in both. It follows in the tradition of His Dark Materials and The Wizard Of Oz, as a young person goes on an adventure with fantastical elements and a cast of characters with varying levels of trustworthiness. Corona’s art brings Middlewest to life; set in the wide expanse of a place that’s flat and full of equal parts tall grass, poverty, and boredom, the book evokes a very particular sense of place even though the time is a bit less firm. The pages are filled with painterly, detailed panels that push at the edges of what is cartoony and what is human anatomy. The dirt and the rust and the dry dust of a tornado alley state nearly jump of the page. The way Corona draws the protagonist’s father is astonishing, translating childhood fears of parental rage into a massive difference in scale and power that will feel familiar to a lot of readers. [Caitlin Rosberg]

Sobek (ShortBox)

It takes real skill to make a comic that eschews most text. Set in ancient Egypt, James Stokoe’s Sobek stars the titular god, who takes the form of an enormous alligator. In other hands, this book would feel inaccessible to a lot of readers who aren’t familiar with the pantheon of ancient Egypt, but Stokoe’s astonishingly detailed art and sense of humor help plant the book on solid ground. There’s very little dialog, which certainly helps the story feel more universal than if he were to focus on the minutiae of the lives that he’s depicting. Sobek is forced to abandon his relaxation and feasting when a priest arrives to tell him that an external threat has arrived and his followers are being killed. The pacing is perfect, a short and sweet story that is entirely self-contained and deeply funny. It has a lot in common with the best kinds of picture books in terms of structure, which will probably be a pleasant surprise to readers who are used to convoluted timelines or emotionally heavy comics. Sobek is a feast for the eyes, and the print quality of the book captures just how much work went into every page of the comic. People and animals are drawn true to form, but so are boats and buildings and weapons, so detailed that you can see individual reeds. Gold foil on the cover signals just how special this book is. [Caitlin Rosberg]

The Immortal Hulk (Marvel)

Nothing can stop The Immortal Hulk. The first year of this series has been an unforgettable ride through a never-ending hall of gamma horrors, and in 2019, the creative team hits new highs by positioning Hulk as the Earth’s greatest threat. Written by Al Ewing with pencils by Joe Bennett, inks by Ruy Jose, colors by Paul Mounts, and letters by Cory Petit, The Immortal Hulk drops bombshells in every single issue, with no other comic replicating the impact of its page-turn reveals. Ewing dives deep into Hulk continuity to weaponize Bruce Banner’s history, unleashing a barrage of increasingly personal attacks from Bruce’s father, best friend, and ex-wife. Bennett has never had the opportunity to explore the horror genre this intensely, and it’s unleashed his superstar potential as he composes pages that are creepy, suspenseful, and build to moments of devastating power. The deaths in this book are gruesomely spectacular, and the creative team makes these new gamma mutates more frightening than any Hulks that came before. Jose’s meticulous inks capture every disturbing detail of Bennett’s monster designs, and Mounts adds a fleshy texture to the saturated green, blue, and red of gamma characters to boost the body horror. The book is a superhero master class, and it shows the value of assembling a passionate creative team and keeping it together for the long haul. [Oliver Sava]

The Structure Is Rotten, Comrade (Fantagraphics)

The main character of The Structure Is Rotten, Comrade is Frunz, an architect who, alongside his father, seeks to level the historic buildings of Yerevan, Armenia’s capital city, and replace them with high-rise buildings of their design. The people of the city, not so taken with the top-down approach to city planning, respond by successfully executing a revolution. It’s a madcap, fast-paced story about a person whose myopic fascination with a single type of building causes him to lose track of what his goal as an architect should be. The book balances its interest in high-minded exploration about how society should be with bizarre, sudden violence, sometimes from literal wrecking balls. Viken Berberian’s writing is propelled by artist Yann Kebbi’s color pencil art, which embraces the chaotic narrative fully. Most pages are busy with streaks and smudges of color with the motion of everyday life in a city layered underneath. Particularly delightful is the way that Kebbi manages to draw Frunz into the world without making him feel a part of it. Even as his plans for the city come crashing down around him, his obliviousness is apparent and something about it makes him quite likable, too, even as he gets his comeuppance. Smart and wild in equal measure, The Structure Is Rotten, Comrade is excellent reading. [Bradley Babendir]

The Wild Storm (DC)

Warren Ellis and Jon Davis-Hunt’s The Wild Storm has often been a slow burn, but when the fuse runs out, the explosions have been oh-so-satisfying. Ellis and Davis-Hunt, along with colorist Steve Buccellato and letter Simon Bowland, have crafted a story that reinterprets Wildstorm characters and concepts with an understated point-of-view that grounds them in a compelling new way. The stakes have been steadily rising over the series’ 24 issues, and while a war has broken out between covert organizations I.O. and Skywatch, a third party emerges as The Authority finally assembles to completely change the battlefield. These final issues have been a thrilling action extravaganza, with the members of The Authority unleashing their power to reclaim the Earth from its secret rulers. These action sequences have an incredible sense of scale, and Davis-Hunt often zooms way out to show the might of these superhuman characters in relation to their much larger surroundings. The interactions between team members are cheeky and fun, and maintaining a sense of humor keeps the book light on its toes as it approaches its conclusion. Ellis’ masterful plotting on this series builds a lot of anticipation for The Authority’s debut, and the pay-off doesn’t disappoint. [Oliver Sava]

This Woman’s Work (Drawn & Quarterly)

Julie Delporte’s graphic memoir (translated from French by Helge Dascher and Aleshia Jensen) explores the often difficult relationship between her creative work and her gender, the latter idea constantly caught between how Delporte herself wishes to understand and enact her gender and how those around her wish her to act and be. She comes to the subject of her own life via an abandoned attempt to write a biography of Finnish author and painter Tove Jansson. Instead, she writes about why that book failed and how she ended up writing this one instead, searching through the traumas of her childhood and the hardships of her adulthood in the process. She follows a narrative and thematic thread as opposed to a chronological one, at all times buoyed by the bright color pencil art that fills the pages of This Woman’s Work. When describing her imagination and ambition, the brightness is an excellent companion and when she dives into heavier territory it is both guardrail and ironic contrast. The final product is a beautiful memoir with a distinct, personal feel. This style, combined with the handwritten, cursive text and Delporte’s beautiful, sparse prose make for an unforgettable book. [Bradley Babendir]

When I Arrived At The Castle (Koyama Press)

Emily Carroll is one of the queens of modern comics horror, and When I Arrived At The Castle came along just in time to remind readers of why. As both a writer and an artist, Carroll excels at slow, creeping horror stories that build dread and sometimes never let the tension break. When I Arrived At The Castle has more of the outward trappings of a horror story than some of her previous work, and a lot of it is on the cover. A cat-woman and a vampire, both with bloody fangs, embrace one another, and even as readers open to the first pages it’s not clear who exactly they are supposed to be rooting for. The book is in a very limited palette of black, white, and red, something of a signature style for Carroll, but she’s far from limited by it. Even with the monstrous nature of the two main characters, it’s the anticipation and dread that make When I Arrived At The Castle frightening. Motivations aren’t entirely clear, and a lot is left to the interpretation of the reader. Filling in those gaps, waiting for what is going to happen next, and wondering why, all fuels the tension that Carroll has masterfully crafted out of a perfectly pared down, spare story. It’s gothic horror at its best, and perfect for readers who can’t wait for October. [Caitlin Rosberg]

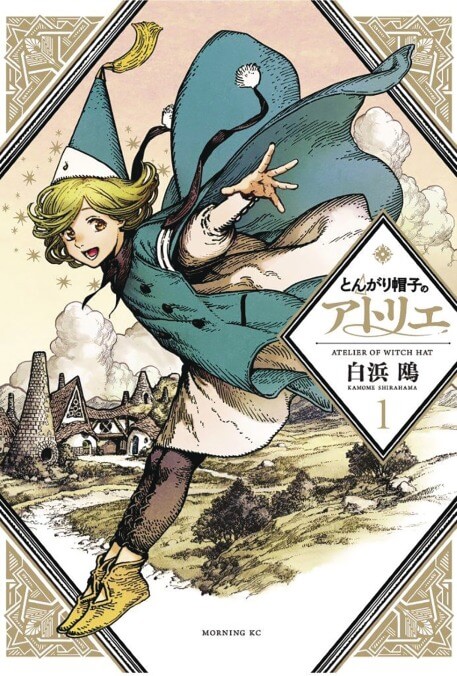

Witch Hat Atelier (Kodansha Comics)

When it comes to enchanting all-ages comics, it doesn’t get much better than Kamome Shirahama’s Witch Hat Atelier. Following a girl desperate to learn the ways of magic, the manga is a charming coming-of-age tale built around realizing your creative potential. The book’s clearly defined magic system makes the fantasy elements feel more real, but it also is essential to the theme of artistic expression. There are firm rules for casting spells, but by thinking outside the box, Coco is able to use old tools in brilliant new ways. The vitality of Shirahama’s characters is matched by the intricacy of her linework, and there’s a sweeping energy to this book that whisks the reader away on a wonderful adventure. Each new locale and character design offers something beautiful to pore over, but it’s hard to slow down when the story moves so swiftly. Readers that do will find plenty of treasures, and Shirahama has put in an astounding amount of work to realize every little element of this magical environment. The ending of the first volume is a cliffhanger that makes the next book irresistible, and thankfully Kodansha isn’t waiting long to release the second volume, which goes on sale this month. [Oliver Sava]