The best films of 2021

West Side Story, The Green Knight, and Licorice Pizza are among our favorite movies of the year

2021 would seem like the strangest year for moviegoing in all of our respective lifetimes were it not for 2020. Things didn’t exactly return to normal over the last 12 months; we’re still very much in a pandemic, and in fact are facing the very real possibility of a return to strict lockdown conditions, if those Omicron numbers are any indication. But thanks to the rollout of vaccines (and subsequent booster shots), movie theaters did scrape out some wins, welcoming audiences again with all the blockbusters delayed over the previous year. Those looking for symbolic evidence that #MoviesAreBack could find it in the triumphant return of James Bond, suiting up for a climactic adventure on the big screen, 18 months after the dramatic announcement that No Time To Die would not be coming soon to a theater near anyone.

Movies never left, of course. Not really. We got plenty of fine ones last year, when theaters were mostly dormant or sparsely occupied, and plenty more over the course of 2021, regardless of fluctuating attendance numbers. As in any other year, most of the films on The A.V. Club’s best-of list were not the kind of major-studio productions mounting some measure of comeback right now; only one of the 25 films in our ranked rundown had a giant budget, and its spectacle was more song-and-dance than cape-and-cowl. You want superheroes? Look for them on the box office charts, not here.

So what did our 10 ballot-filing contributors gravitate towards instead? Westerns and musicals. Anthology projects and stage adaptations. A joyous concert film and a melancholy animated documentary. If these movies had anything in common beyond their general excellence, it was the opportunity to see each of them on the big screen—a once-normal privilege that became an abnormal (and sometimes stressful) treat in 2021, and which we hope won’t become a total pleasure of the past, again, in 2022.

2021 would seem like the strangest year for moviegoing in all of our respective lifetimes were it not for 2020. Things didn’t exactly return to normal over the last 12 months; we’re still very much in a pandemic, and in fact are facing the very real possibility of a return to strict lockdown conditions, if those Omicron numbers are any indication. But thanks to the rollout of vaccines (and subsequent booster shots), movie theaters did scrape out some wins, welcoming audiences again with all the blockbusters delayed over the previous year. Those looking for symbolic evidence that #MoviesAreBack could find it in the triumphant return of James Bond, suiting up for a climactic adventure on the big screen, 18 months after the dramatic announcement that would not be coming soon to a theater near anyone.Movies never left, of course. Not really. We got plenty of fine ones , when theaters were mostly dormant or sparsely occupied, and plenty more over the course of 2021, regardless of fluctuating attendance numbers. As in any other year, most of the films on The A.V. Club’s best-of list were not the kind of major-studio productions mounting some measure of comeback right now; only one of the 25 films in our ranked rundown had a giant budget, and its spectacle was more song-and-dance than cape-and-cowl. You want superheroes? Look for them on the box office charts, not here.So what did our gravitate towards instead? Westerns and musicals. Anthology projects and stage adaptations. A joyous concert film and a melancholy animated documentary. If these movies had anything in common beyond their general excellence, it was the opportunity to see each of them on the big screen—a once-normal privilege that became an abnormal (and sometimes stressful) treat in 2021, and which we hope won’t become a total pleasure of the past, again, in 2022.

When film historians of the future look back at 2021, Zola will be remembered as a turning point in how the medium engaged with social media. Janicza Bravo approaches the first major movie based on a Twitter thread with the nimbleness and wit of a digital native, using cheeky sound effects and dynamic direction to put viewers inside of A’Ziah “Zola” King’s wild tweetstorm about a disastrous weekend working at a strip club in Florida. But what really elevates her road-trip picture above curio status is its cast. The supporting players are especially strong, with Colman Domingo, Riley Keough, and Nicolas Braun providing three of the funniest, slipperiest, most engaging lowlife performances to a year that was filthy with them. [Katie Rife]

Two strangers—divided by age, nationality, and language—go about their daily routines in solitude, until their lives intersect during an erotic encounter in a Hong Kong hotel room. That’s the long and the short (emphasis on the long, given how characteristically protracted the takes are) of this latest meditative drama from Tsai Ming-Liang. With Days, the great Malaysian-by-way-of-Taiwan director drops any pretense of catering at all to a mainstream audience: What passes for a plot is mostly mundane activity, the dialogue reduced to an unscripted, un-subtitled minimum. Yet those who can adjust their attention span to Tsai’s demands on it will discover a film fluent in the loneliness so many have endured these past couple years. In the aging visage of the filmmaker’s perennial star, Lee Kang-Sheng, one can see the emotional cycle of our moment: the agony of isolation, the ecstasy of connection, and how one bleeds back into the other as together gives way again to apart. [A.A. Dowd]

In this striking animated documentary, Danish filmmaker Jonas Poher Rasmussen interviews longtime friend Amin (a pseudonym to safeguard the subject’s identity), whose family escaped their homeland of Afghanistan in the turbulent 1980s. Over the course of the film, Amin orally chronicles his harrowing odyssey from Kabul to Copenhagen, with a long stint in Russia, while reflecting on his fear of coming out to his traditional parents. Here, animation provides more than just the cover of anonymity; it’s the perfect vehicle to visualize the man’s richly visceral memories, getting us closer to the sensory truth of his journey than reenactments ever could. In grappling with a past he had buried for so long, Amin rediscovers a part of himself and his history he was in danger of forgetting. His contrasting fright and elation, summoned through recounted anecdote, makes Flee an especially complex portrait of the refugee/migrant experience. [Carlos Aguilar]

For his first “solo” film made without the participation of his brother Ethan, Joel Coen gets back to the Shakespearean roots that fans of the erstwhile duo may not have realized they had. It turns out that the mordantly noirish schemers that populate their impressive filmography might actually be descendants of Lord and Lady Macbeth, sharply played here by Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand as an older couple taking one last grab for power. Coen’s take on Macbeth doesn’t look or sound exactly like any of his other movies. In an age of remaking by excess, he subtracts, draining the color from the images and leaving only black-and-white to capture the stunning, borderline abstract sets. Washington and McDormand perform in a stage-cinema hybrid dream state, ghostly and fatalistic. Not only is this a worthy production of a great play, it’s a fascinating restart point for a director proving he can make exciting work on his own. [Jesse Hassenger]

Welcome to the island of Fårö, a scenic getaway where the lingering essence of former inhabitant Ingmar Bergman overcasts the leisurely sightseeing with existential isolation and reminders of life’s many unfulfilled expectations. Mia Hansen-Løve flirts with autobiography as her filmmaker stand-in goes on holiday with her slightly better-known partner to break her writer’s block and invents a fictive alter ego of her own. The poignant interlude spent inside the character’s in-progress screenplay shows how an artist might use their work as a method of processing or revising their circumstances, reframing everything around it as a revealing roman à clef for Hansen-Løve and ex Olivier Assayas. It’s no great stretch to conclude that she’s mapped the rocky terrain of a past relationship with candor and emotional intelligence; the ecstatic dance scene soundtracked by Sweden’s finest non-Bergman cultural export—ABBA—is just the gravy on the meatballs. [Charles Bramesco]

Ryusuke Hamaguchi makes films that are so deceptively even-keeled it can sometimes take a while to process just how deep their still waters run. That makes him a fascinating match for playwright Anton Chekhov, whose world-famous work deploys its own unique tonal reveries for unexpected aims. Centered around an experimental, multilingual production of Uncle Vanya, Drive My Car is a meditation on grief, art, communication, and the silences that say more than words ever could. At three hours long, it’s not a breezy watch, per se. But Hamaguchi uses that extended runtime to craft a contemplative, almost hypnotic tone in which patience is a virtue that pays dividends. Anchored by stellar performances from Hidetoshi Nishijima as a taciturn theater director and Tōko Miura as his mysterious driver, this Japanese drama is an enthralling ride. [Caroline Siede]

Maybe it should come as no surprise that Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir: Part II is at least as good as her earlier , considering they were conceived together as a two-part semi-autobiographical project about Hogg’s time in film school. Yet it’s still impressive to see the British director add to the small list of sequels that not only match but possibly even improve upon their acclaimed predecessors. Part II follows Julie (Honor Swinton Byrne), still reeling from the death of her heroin-addicted lover by overdose, as she throws all her energy into making a short film about the relationship. Hogg perfectly captures the minutiae of student film production in all its stressful non-glory, but she also portrays how art and art-making can be a catalyst for processing emotions; closure might be impossible, but catharsis can be achieved, if only in fleeting moments. On top of all that, the film features a stellar comedic turn from Richard Ayoade, who steals the show as an Orson Welles-like director constantly on the brink of a tantrum. [Vikram Murthi]

Every enlightening feature Swedish master Roy Andersson has made over the last two decades consists of meticulously conceived vignettes on the absurdity of the human condition. His most recent compilation of peculiar scenarios includes a priest whose wavering faith sends him on a quest for solace, a prideful man annoyed at running into a smug old classmate, a public display of spontaneous joy in the form of dance, a storefront romance, and even a segment dedicated to Hitler’s final moments. Shooting his pale microcosms on enormous sets in his Stockholm studio, the director mines dry humor and philosophical queries mostly from quotidian tragedies and triumphs, with some touches of political commentary. Whether this will prove to be Andersson’s swan song remains to be seen. If it does, he’ll have departed with his creative idiosyncrasy fully intact. [Carlos Aguilar]

Sparks flew in 2021: Russell and Ron Mael were the subject of a , and they also conceived and wrote the year’s strangest musical, outsourcing its direction to France’s Leos Carax (). Almost entirely sung, Annette tells the story of the tabloid-headline relationship between a provocative stand-up comic (Adam Driver) and a beloved opera singer (Marion Cotillard); he metaphorically kills for a living while she symbolically dies every night, and for a while the film looks like just another study of toxic masculinity. But the couple have a daughter, Annette, who’s represented by a series of uncanny-valley puppets and turns out to possess the world’s most beautiful singing voice. Artifice and its seductive dangers become Annette’s true subject, with the Maels’ deliberately repetitive numbers calling attention to the genre’s structural scaffolding. The result isn’t to every taste (to put it mildly, hence its relatively low placement here), but those on its wavelength will be awed. [Mike D’Angelo]

Even if you haven’t seen Titane, you probably know two things about it: that Spike Lee prematurely revealed that it had won the top prize at Cannes, the Palme d’Or, this summer; and that someone has sex with a car. (Actually, it’s two cars, but who’s counting?) Yet even with that information in mind, Julia Ducournau’s follow-up to the cannibal coming-of-age fable defies every expectation. Centered around the largely wordless performance of Agathe Rousselle in one of the most impressive acting debuts in recent memory, Titane breaks new ground in “body horror” by having skulls, wombs, and veins pullulating with grease, metal, and gasoline. For all the shock value of the film, which concerns the unlikely relationship that develops between Rousselle’s on-the-lam criminal and a traumatized firefighter played by Vincent Lindon, it’s ultimately as moving as it is lurid and as sweet as it is grotesque: a sensitive meditation on gender, family, sex, and grief, just super-charged with Ducournau’s now-signature intensity. [Leila Latif]

A young woman considers blowing up her galpal’s budding romance, but has second thoughts about it. An afternoon’s would-be honeypot scheme turns into an encounter of chaster, purer intimacy. An unexpected reunion between old classmates takes an even more unexpected turn, before the two stumble into a gentle form of therapeutic transference. Bittersweet ironies flutter all around this touching triptych from Ryusuke Hamaguchi, who works in a more immediate register of feeling than the often opaque Murakami-isms of the film that falls five spots back on this list, Drive My Car. These elegantly told missed connections—one refused, one ruined, one salvaged—jointly form a patchwork picture of tragedy qualified by time. Solitude is difficult, but we learn to live with it. We sabotage ourselves, and eventually move on. We heal the wounds of the past with the present’s love and mercy. [Charles Bramesco]

In the spirit of playful, provocative cinematic essayists like Jean-Luc Godard and , inventive Romanian filmmaker Radu Jude blends sharp social satire with avant-garde tomfoolery. Bad Luck Banging has a simple plot: Katia Pascariu plays Emi, a teacher publicly embarrassed and professionally embattled after a sex video she made with her husband gets widely distributed on the internet. Jude approaches the premise from different directions, in what amounts to a series of fascinating short films: a day in the life of an increasingly commercialized Romania; a playlet about the hypocrisy and bigotry of a moralizing mob; a freeform riff on the meaning of words. Expressly set during the current pandemic, Bad Luck Banging is a frighteningly accurate snapshot of today, right down to the angry parents exploiting a moment of upheaval to roll back decades of social progress. [Noel Murray]

Paul Schrader has worked within many genres throughout his career as a screenwriter and director, but his specialty has always been movies like , Hardcore, and , about dangerously obsessive and alienated loners. He’s made another great one in The Card Counter, with Oscar Isaac delivering a darkly magnetic performance as an Army vet going by the name of William Tell, who spent nearly a decade in prison for war crimes before becoming a shrewd professional gambler. When the opportunity arises to atone for past sins, William dispenses with his usual cautious lifestyle, even though—as is often the case for Schrader protagonists—no one else is really paying much attention to whether his mission succeeds or fails. He’s one of Schrader’s usual spiritually exhausted men, trying to do the right thing for a world largely uninterested in heroism. [Noel Murray]

The Worst Person In The World has multiple hallmarks of an overstuffed literary adaptation: narration that comes and goes, narrative divided into episodic chapters, a cumbersome and unclear timespan. But director and co-writer Joachim Trier isn’t actually wrestling a novel into submission; he’s using an original film to chronicle the various careers, hobbies, and relationships of twenty-to-thirtysomething Julie (Renate Reinsve), with a novel-in-stories progression through moments deceptively small and surprisingly seismic. Julie, played beautifully by Reinsve, remains at the center even as Trier cleverly positions her looking through windows into other lives: the husband and wife loudly fighting in the next room; the cancer patient air-drumming with his headphones on; an anonymous couple on the street, frozen in a kiss during one reality-blurring stunner of a scene. Chapters come and go; the book, Trier understands, is never finished. [Jesse Hassenger]

The blunt title, the John Wick-esque premise (middle-aged hermit hunts down the people who stole his beloved truffle pig), and the words “starring Nicolas Cage” primed expectations for a tongue-in-cheek, over-the-top revenge thriller. Instead, first-time director Michael Sarnoski serves up a disarmingly sincere and heartfelt portrait of curdled grief, while simultaneously exploring the Proustian ways in which food can do more than merely sustain us. That’s not to say that the film doesn’t have its enjoyably offbeat touches, like the protagonist’s visit to Portland’s secret haute cuisine fight club, which sees restaurant workers bid to pummel tyrannical chefs. And Cage does suddenly yell into a little kid’s face at one point. But it’s his beautifully internalized embodiment of sorrow mixed with grim determination that sets the tone, and Pig’s ultimate catharsis arrives in forms—one culinary, the other musical—that are unexpected and genuinely moving. [Mike D’Angelo]

If Summer Of Soul were just one of the best concert films of the year, that would likely be enough to earn it a spot on this list. But director Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson takes things one step further by using his stunningly remastered footage of the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival as a springboard to look at American history through the lens of Black culture. The structure here seems obvious in retrospect: Use electrifying performances from the likes of Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, Gladys Knight & The Pips, and Mahalia Jackson as jumping-off points to examine various socio-political topics. But it takes a deft hand to make that kind of complex historical streamlining seem effortless. Summer Of Soul filters education and reclamation through the lens of celebration. That makes it a joyous crowd-pleaser with a pointed perspective and a rhythmic spirit. [Caroline Siede]

Imagine being awoken in the middle of the night by a loud, unidentifiable noise, subsequently hearing it again at random intervals, and gradually realizing that the increasingly aggressive sound is confined to your own baffled skull. That’s the bizarre starting point (inspired by an actual phenomenon, “exploding head syndrome”) for the latest stunner from Apichatpong “Joe” Weerasethakul (), who strays from his comfort zone by shooting in Colombia rather than his native Thailand and working with a celebrity instead of his usual non-pros. Tilda Swinton plays the afflicted woman, though her character’s really a conduit for something gravely mysterious, hovering just at the edge of perception. Joe’s long been cinema’s most adventurous explorer of liminal spaces, and Memoria—which kicks off its one-theater-at-a-time national roadshow tour next week, and will allegedly never be made available to view at home—is an immersive, mesmerizing trek into the casually uncanny. [Mike D’Angelo]

What if the dream factory conjured a real dream again, and no one showed up? The box-office failure of West Side Story is bad news for those invested in Hollywood spectacles with more twinkling in their eyes than the promise of a franchise. Part of the magic of Steven Spielberg’s majestic adaptation is how it feels both classical and modern. The playwright Tony Kushner gracefully upgrades certain elements, teetering the eternal Romeo And Juliet clash of warring gangs towards a genuine balance of perspective and sympathies. Meanwhile, Spielberg brings the timeless story alive again through brilliant casting and the virtuosic verve of his staging, finally applied to a genre of pure song and dance. Still, in the end, what they’ve all emerged with is a stirringly, reverently faithful West Side Story: a new production that understands the mythic appeal of the material and the undimmed power of maybe the greatest songbook in the history of stage and screen musicals. Sometimes, they do make ’em like they used to. But for how much longer? [A.A. Dowd]

English national identity is an extremely slippery subject, mired in centuries of ambition, pomposity, and small island tribalism. Given how the past decade has crescendoed with debates about what the country really stands for, it was apt of David Lowery to choose this moment to re-examine one of its founding legends. Based on a 14th-century Arthurian poem, The Green Knight is a spellbinding epic of myth and masculinity, with a never-better Dev Patel as the foolhardy but sympathetic Gawain, an aspiring adventurer laid asunder by his ego, challenging the titular monstrous knight to a “game” he is doomed to lose. Gawain’s perilous, episodic quest takes him across the land, raising questions along the way about what he, and it, are fated to become. Gifted with an uncommon eye for breathtaking British landscape, this American director has captured some of the very best of the nation across the sea, while unearthing much of the rot clogging its foundations. [Leila Latif]

“You can’t even keep your own story straight,” Alana (Alana Haim) tells Gary (Cooper Hoffman) early in Licorice Pizza, Paul Thomas Anderson’s third and flat-out loveliest crack at chronicling Los Angeles in the 1970s. This description actually applies to both of them: two ill-fitting hustlers, one frustrated in her 20s and the other precocious in his teens, trying to piece together their next steps through various small businesses and hijinks. Though their unsteady love story is PTA’s most immediately accessible movie in years, he still elides or obscures certain narrative details, as in his more obscure work. Here he uses that elusiveness for a different effect, blurring variously strange, magical, and harrowing adventures into a heady rush of time’s uncertain but inexorable passage. Maybe that’s why the much-discussed age gap between the two heroes registers as more unusual romantic obstacle than flashing red morality alarm: They’re mutually unstuck from both childhood and adulthood, forever (or just for now) running back toward each other. [Jesse Hassenger]

“No good deed goes unpunished,” read early reviews and festival program synopses of A Hero. That pithy idiom doesn’t begin to capture the twists and turns of motivation that drive Asghar Farhadi’s powerhouse drama about an imprisoned calligrapher (Amir Jadidi) who commits an act of apparent altruism that creeps into a web of deception entangling multiple parties. Of course, any attempt to summarize this Iranian filmmaker’s intricate plotting is bound to resort to simplifications. A Hero might be his most morally and dramatically complex since , with each new complication further muddying our sympathies and peeling back more layers of societal critique, until a gripping character study has become an indictment of a whole culture’s (maybe a whole world’s) value system. In its examination of the fickle nature of internet fame, A Hero can even be described as Asghar Farhadi’s take on the milkshake duck phenomenon—another simplification, yes, but one that reflects the firm finger the director has on the pulse of modern life. [A.A. Dowd]

Toxic masculinity is as much a part of the mythology of the American West as cowboy hats and the open range. With The Power Of The Dog, writer-director Jane Campion tugs on this thread with her signature focus on twisted relationship dynamics in majestic natural surroundings. Although it’s set in Montana, the film was shot in New Zealand, which gives it an unsettled, slightly “off” quality. The same applies to star Benedict Cumberbatch, playing against type as a mean-spirited rancher; he’s an odd fit for the role, but that’s a brilliant strategy for a character who’s painfully uncomfortable in his own skin. Subversions and acts of subterfuge abound—both in the text and in Campion’s filmmaking, which imbues even the sunniest, most carefree moments with a poisonous aftertaste. [Katie Rife]

When Mikey Saber (Simon Rex), the dirtbag former porn star at the heart of Sean Baker’s new movie, returns broke, beat up, and homeless to his small hometown of Texas City, Texas, he seems to have nowhere to go but up. But Mikey, as it quickly becomes clear, has never hit a rock bottom he can’t push through to reach unforeseen depths of degeneracy; no sooner has he regained the trust of his estranged wife and mother-in-law than he sets his sights on Strawberry (Suzanna Son), a starry-eyed teenager who works at the local donut shop and who this washed-up parasite sees as his ticket back into the Los Angeles adult film industry. Baker’s ethnographic eye, combined with Rex’s stellar motor-mouthed turn, enliven both the high comedy and minor-key tragedy of Red Rocket. Crucially, it’s refreshing to watch a film that trusts its audience enough to make up their own minds about the charming grifters who populate and prowl our culture. [Vikram Murthi]

Although it arrived in the wake of director Celine Sciamma’s international breakthrough, the rapturous romance , Petite Maman is more in line with the French writer-director’s earlier work. That means it’s a tender, delicate coming-of-age story, bathed in a warm light—both literal and figurative—that makes you want to curl up and take a nap like a cat in a sunbeam. A magical realist ghost story about the transcendent bonds between mothers and their children, Petite Maman takes a premise straight out of an extremely popular ’80s comedy (to say which one would spoil the plot) and reinvents it on both an aesthetic and an emotional level. It does so in only 72 minutes, but this little jewel of a film has a poetic impact that lingers far beyond its modest running time. [Katie Rife]

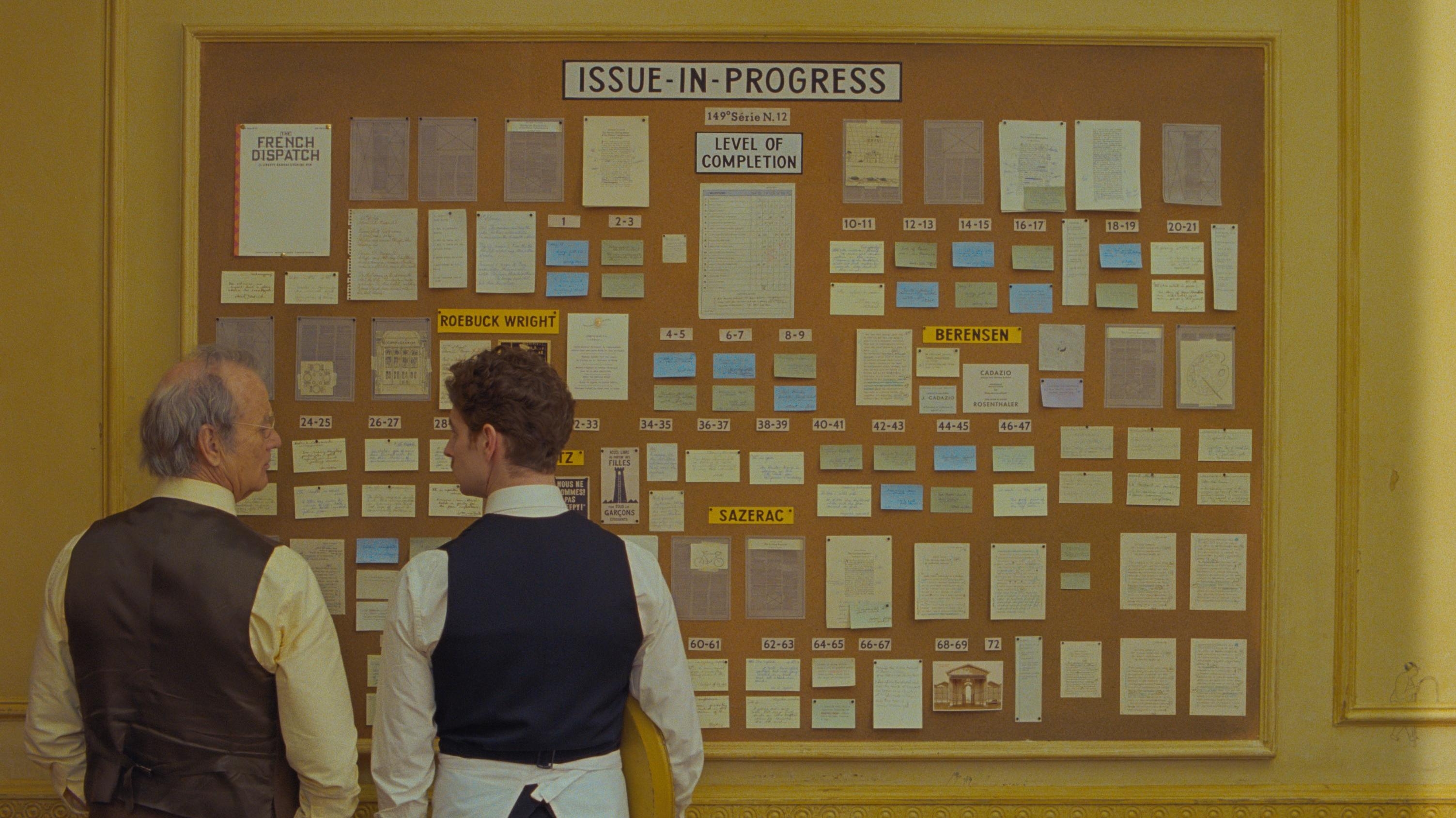

A glorious nesting doll of a movie. Furthering his obsession with building frames around frames, Wes Anderson presents his first anthology film as the final issue of a revered periodical not-so-loosely modeled on The New Yorker—a sophisticated structural gimmick that allows him to tell stories within stories within more stories, riffing on the absurdities of, say, the modern art world while also centering the perspective of the intrepid reporters navigating it. The French Dispatch has been confused, as Anderson’s work so often is, for an empty exercise in meticulously dioramic style. As usual, though, the writer-director smuggles profundities and bittersweet insights into the supposedly hollow center of his brilliant comic picaresques. Within this Matryoshka, you’ll find affecting performances (including Jeffrey Wright’s lovely Wes World take on James Baldwin), affectionate cartoon Francophilia, and a dizzyingly dense pastiche of the various artworks that have sparked Anderson’s imagination. Finally, at center is a eulogy for the Arthur Howitzer Juniors of the world: a winsome tribute to unfashionable editorial integrity, celebrating a half-remembered, half-imagined era when the owners of publications actually gave two shits about their writers and the subjects they wrote about. Today, that’s a reality that seems as unreal—and as pleasingly fantastical—as an isle of dogs, a moonrise kingdom, or the house on Archer Avenue. [A.A. Dowd]

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.