The best movie scenes of 2020

Any movie can achieve a moment of greatness. We’re talking about those few minutes that stick with you for a lifetime, even after everything around them fades from memory. You’ve heard of a TV show jumping the shark? This is the shark jumping Sam Jackson; when the world has forgotten Deep Blue Sea, his gloriously interrupted pep talk will live on in the collective imagination. It’s a principle we here at The A.V. Club try to keep in mind every December, when we’re putting together the list you’re about to scroll through. Sure, there’s inevitable overlap between a year’s great movies and its best individual scenes, which is why some of the titles appearing in this feature will show up again next week, when we count down our favorite whole films of 2020. But great scenes can come from all sorts of movies—even, say, a nattering family-friendly video game adaptation we’d otherwise prefer to forget. You’ll find that and more on the list that follows, unranked save for the selection of a single scene that we settled on as our consensus favorite of 2020. Oh, and reader beware: Although we tried to stick the more revealing descriptions toward the end, there will be spoilers throughout. Because no matter where the scene comes from, explaining its greatness requires some, you know, explaining.

Any movie can achieve a moment of greatness. We’re talking about those few minutes that stick with you for a lifetime, even after everything around them fades from memory. You’ve heard of a TV show jumping the shark? This is the shark jumping Sam Jackson; when the world has forgotten Deep Blue Sea, his will live on in the collective imagination. It’s a principle we here at The A.V. Club try to keep in mind every December, when we’re putting together the list you’re about to scroll through. Sure, there’s inevitable overlap between a year’s great movies and its best individual scenes, which is why some of the titles appearing in this feature will show up again next week, when we count down our favorite whole films of 2020. But great scenes can come from all sorts of movies—even, say, a nattering family-friendly video game adaptation we’d otherwise prefer to forget. You’ll find that and more on the list that follows, unranked save for the selection of a single scene that we settled on as our consensus favorite of 2020. Oh, and reader beware: Although we tried to stick the more revealing descriptions toward the end, there will be spoilers throughout. Because no matter where the scene comes from, explaining its greatness requires some, you know, explaining.

Regardless of how you classify Small Axe, the five-film anthology Steve McQueen made for the BBC (the final two installments hit Prime this Friday and next), there’s little denying that it offers the most ecstatic, transporting few minutes to grace screens this year. They arrive halfway through the second entry in the series, Lovers Rock, which is set almost entirely at a house party in the West London of the 1980s. The DJs cue up Janet Kay’s 1979 reggae hit “Silly Games,” and as the song plays out in its swoony entirety, McQueen keeps his camera locked on faces and bodies, capturing the joy and desire passing across the dance floor like electric currents. Then the music cuts out and everyone keeps singing, the song taking on the euphoric quality of a hymn. Without dialogue, McQueen conveys the full significance of his backdrop—how house parties like this one offered Black Londoners fun, community, and brief refuge from the racism of life in the city. But for as vividly as Lovers Rock captures its particular milieu, it also speaks to the powerful desire for connection so many have felt over these lonely few months. More than just the vicarious party of the year, its centerpiece sing-along feels like a requiem for communal experience, specific and universal, rapturous and bittersweet. [A.A. Dowd]

At first, the brilliance of the nine-minute opening shot/sequence of Michael Angelo Covino and Kyle Marvin’s The Climb seems to spring from an old aphorism: location, location, location. Two friends bike through the French countryside, shooting the shit about life and love. But when they begin an ascent, Mike (Covino) lets loose a piece of information that pops the bubble of contentment Kyle (Marvin) calls home: He’s been sleeping with his buddy’s fiancée for years. The peace cracks, but the pace holds, because the two are pedaling, winded, up a big hill. Essentially a remake of the pair’s short of the same name, the scene is marvelously staged in a single, extended take. But its genius lies not just in Covino’s direction but also in the character beats he and his writing partner offer as actors. They set the tone of this bittersweet buddy comedy and the complex relationship at its center. [Allison Shoemaker]

On paper, the opening scene of Leigh Whannell’s The Invisible Man doesn’t sound terribly exciting. It’s night in a lavish modern house, and a woman, Elisabeth Moss’ Cecilia, is trying to get dressed without waking her partner. Yet what follows qualifies as an impeccably crafted gauntlet of nail-biting stress, as the director and his star wordlessly convey the dangerous stakes of Cecilia’s late-night escape plan: We don’t need the details of the relationship to know that it would be very, very bad if the man in the bed woke up—that reality is scrawled all over Moss’ breathless performance. As the seconds tick by, we wait for Whannell to drop the other shoe; when a character accidentally kicking a dog bowl is a genuinely heart-stopping turn, you know you’re watching a master class in tension. [Alex McLevy]

Too many filmmakers put too little effort into crafting their movie’s opening minutes, which should vividly establish the world—unique in some respect, hopefully—that viewers will inhabit for the next couple of hours. Andrew Patterson doesn’t make that mistake. While The Vast Of Night announces itself up front as a sort of Twilight Zone riff, there’s nothing spooky or mysterious about the elaborately choreographed sequence that introduces its two main characters. In 1950s New Mexico, teen disc jockey Everett (Jake Horowitz) wanders his high school’s gym prior to a basketball game, chatting up various friends and teachers, while the slightly younger Fay (Sierra McCormick) bugs him to help field-test her brand-new tape recorder. Little of this business (and literal busy-ness) matters to the narrative that will soon emerge. It’s just a bravura means of dialing us into The Vast Of Night’s stylized patter (“I don’t know what you just said, Fay. You sound like a mouse being eaten by a possum.”), naturalistically mannered performances, and slightly warped period flavor. By the time these kids head outside, you’re ready to follow them anywhere. [Mike D’Angelo]

The terrific micro-set piece that comes early in John Hyams’ back-to-basics abduction thriller is a lesson in creating big-screen spectacle without a big budget. In fact, there’s no action in this single-take sequence, in which the widowed heroine (who’s being stalked, Duel-style, by a mysterious SUV) makes an innocuous phone call from a dimly lit rest stop. Oners in modern thrillers usually involve a lot of pizzazz-y camera movement, but Hyams keeps to one vantage point. It’s all in the timing, with slow pans and pulled focus tracking distant extras in the background like potential threats, creating one of the year’s most suspenseful scenes. [Ignatiy Vishnevestky]

Poise and dignity are the words that first spring to mind when describing Sibil “Fox Rich” Richardson, the subject of Garrett Bradley’s lyrical documentary Time. Fighting to free her husband 20 years into his 60-year prison sentence, Richardson makes near daily phone calls to the courthouse looking for updates on his re-sentencing appeal—a Sisyphean task she approaches with herculean patience. So it’s startling when she finally snaps. Upon learning that a judge’s secretary didn’t even check for the updates she just claimed weren’t available, Richardson initially tries to laugh off the bureaucratic absurdity. But the emotions beneath her unflappable exterior finally bubble to the surface in a stream-of-consciousness monologue fueled by two decades of pent-up frustration. As reflected in that unfiltered moment, Time is a damning look at the dehumanization of the prison–industrial complex—both for those behind bars and those left in limbo on the outside. [Caroline Siede]

To the (admittedly arguable) extent that Jeff Fowler’s Sega adaptation works at all, it’s in leveraging its most consistently cartoony asset—and we’re not talking about the CGI rodent. No, the biggest pleasure to be derived from Sonic The Hedgehog is in watching Jim Carrey go the full Jim Carrey, throwing everything he has at his performance as video game no-goodnik Dr. Robotnik—a literally mustache-twirling turn that brings the actor’s manic energy and gift for slapstick back to the fore after what feels like years of hibernation. Nowhere is that apparently limitless energy clearer than the sequence (largely wordless, in a film that otherwise never shuts up) in which Carrey dances around his evil lab, humping the scenery to the tune of The Poppy Family’s “Where Evil Grows.” It’s goofy, over the top… and completely magnetic and hilarious. Vintage Carrey, in other words. [William Hughes]

For the most part, Borat Subsequent Moviefilm has a weaker bite than the original. Yet the addition of Tutar (Maria Bakalova), Borat’s daughter and the “oldest unmarried woman in Kazakhstan,” gives Sacha Baron Cohen’s harebrained social experiment new, surprisingly feminist depths. Following her “American” makeover, Tutar and Dad attend a debutante ball and perform their country’s traditional “moon blood” fertility dance for a conservative audience. When Tutar breaks out her rugged dance moves, it’s out of the ordinary but ultimately kind of charming—the spectators warm up to the duo and begin to clap. Then Tutar hikes her gown up over her waist and reveals blood-soaked underwear. What the first Borat’s infamous fight scene did with male nudity, the sequel does with the female anatomy. It’s an outrageous, genuinely surprising moment, drawing shock and anger from the scarred onlookers. It’s also triumphantly funny. [Beatrice Loayza]

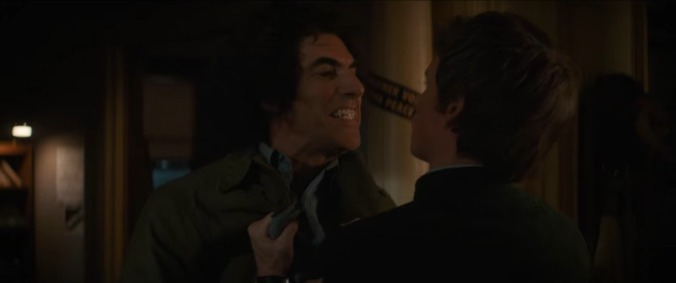

Aaron Sorkin has a lot of bad habits as a screenwriter, but one thing he’s always been good at—as far back as A Few Good Men—is framing ideological debates so that both sides get their points across, clearly and concisely. Most of The Trial Of The Chicago 7 is about the conflict between a conservative legal establishment and the radical free-speech advocates they’re trying to silence. But there are divisions among the radicals, too, and in one of the movie’s most thrillingly Sorkin-esque scenes, clean-cut progressive Tom Hayden (Eddie Redmayne) snaps at hippie provocateur Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen), arguing that his loud and clownish antics may draw crowds but they won’t win votes. Hoffman counters, saying that what matters is education and engagement, not compromise. It’s a short but clarifying debate, sketching out the framework for a fight that American leftists are still having, 50 years later. [Noel Murray]

One of the major pleasures of Sofia Coppola’s new movie is the spectacle of Bill Murray playing, essentially, a version of himself: a carefree celebrity fuck-around who lives life like it’s one endless vacation. Of course, the fact that his seventysomething character, Felix, has never faced any real consequences for his decades of womanizing and joyriding also speaks to the enormous privilege he’s enjoyed. That much is made clear in what may be the film’s funniest but also most pointed scene, when Felix, speeding around New York in a convertible with daughter Laura (Rashida Jones), gets pulled over by a police officer and successfully sweet-talks his way out of a speeding ticket. It’s a classic Murray moment, a devious charm offensive… and also a demonstration of how men like him and his onscreen alter ego live by different rules. “It must be very nice to be you,” Laura incredulously remarks. “I wouldn’t have it any other way,” Felix replies. Yeah, no shit, dude. [A.A. Dowd]

As with the other films Charlie Kaufman has directed, I’m Thinking Of Ending Things sometimes threatens to obscure itself with symbolism and dream logic. But Kaufman is brilliant at grounding his weirdness in quotidian details, and the Ending Things scene where Jake (Jesse Plemons) and his tenuous girlfriend, Lucy (Jessie Buckley), sit down to dinner with his parents (Toni Collette and David Thewlis) is a 10-minute masterwork of realistic discomfort. Jake seethes with embarrassment as his father makes blithe pronouncements about art and Billy Crystal, his overeager mother nervously forces joviality, and Lucy tells a protracted meet-cute story involving bar trivia; the characters are rarely able to share Kaufman’s narrow frame, creating a conversation that’s both continuous and out of sync. Thewlis gets some of the movie’s biggest laughs by actively refusing to accept the abstractions Kaufman himself seems to prefer: “How can a picture of a field be sad without a sad person looking sad in the field?” he demands. Then again, maybe Kaufman isn’t as obtuse he seems: The scene ends with Lucy looking sad—and alone. [Jesse Hassenger]

Small children fear the dark and haven’t yet learned to relish unconsciousness, so getting them to sleep can be an ordeal. Hence the enduring appeal of the bedtime story, meant to lull kids into a more receptive state, or just plain exhaust them with verbiage. Ingimundur (Ingvar Eggert Sigurdsson), however, is going through a rough time, which puts a startlingly sadistic spin on the tale that he tells to his granddaughter (Ída Mekkín Hlynsdóttir) one night. It’s closer to being the sort of yarn one spins around the campfire, concerning a reanimated corpse seeking its stolen liver (a variation on “”), and Ingimundur persists even as the little girl buries herself underneath the covers and shrieks for him to stop. There’s never any question that he loves her, and the scene concludes without any sense of lingering trauma; one could chalk it up to misguided playfulness. But it also suggests a man on the verge of snapping. [Mike D’Angelo]

In surveying the vast workings of Boston’s municipal administration, Frederick Wiseman’s City Hall has something of a central figure in Mayor Marty Walsh, whom we see at public functions, meetings, and speaking engagements of all sorts. But he is significantly absent from the film’s most riveting passage: a public discussion regarding a proposed cannabis dispensary in Dorchester, one of Boston’s most ethnically diverse and economically underserved neighborhoods. For over 20 minutes, we see a group of businessmen engage with the area’s concerned citizens, and the results are by turns tense and confrontational, exasperating and rousing. The scene also illustrates just how liberal entreaties and practiced political rhetoric—e.g., appeals to “community,” “diversity,” and the city’s “majority minority” population—can, under some circumstances, sound like so much pandering PR. Far from the chambers of city hall, Wiseman takes a hard, necessary look at the ground-level realities of talk as the lifeblood of political action. [Lawrence Garcia]

Just about any five minutes plucked at random from Diao Yinan’s stylish manhunt thriller might rank among the coolest scenes of the year; the film’s a slick set-piece machine whose plot is pure pretext for the movement of bodies through neon-lit spaces. But among its most mesmerizing passages is the one that begins with our gangster hero (Hu Ge), who’s on the lam after accidentally killing a cop, falling into the clutches of thugs hoping to turn in his body for the reward. A bloody, chaotic escape leads to a mad chase staged across multiple axes, as the alleyways become a labyrinth of treacherous sight lines and death from above. Diao dazzlingly abstracts some of the action, turning a feverish pursuit into a shadow play and implying one casualty with an offscreen gunshot and a drop of blood falling onto a goon’s face. Not that he skimps on violence; the scene commences with murder by umbrella—maybe the most surreal image in a movie that unfolds in a twilight zone of noir unreality. [A.A. Dowd]

It’s no surprise that storied Gina Prince-Bythewood would find a moment to showcase love in her big action drama, The Old Guard. But in a media landscape where blockbusters regularly expect praise for the briefest of “exclusively gay moments,” it’s astonishing to see a comic book movie place a queer love story at its center. In one of the film’s most memorable character beats, immortal warrior Joe (Marwan Kenzari) confronts a tossed-off homophobic joke with a monologue so eloquently impassioned as to make any mere mortal blush at the inadequacies of their own affections: “I love this man beyond measure and reason. He’s not my ‘boyfriend.’ He’s all and he’s more,” Joe explains with a simple, sincere conviction befitting Kenzari’s drama school roots. When Nicky (Luca Marinelli) playfully calls him an “incurable romantic” in response, the duo cements their status as one of superhero cinema’s most winning couples. [Caroline Siede]

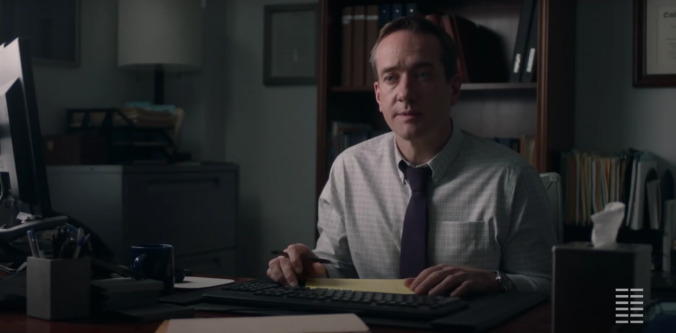

Kitty Green’s The Assistant is all about the system that allows a Harvey Weinstein-like mogul to prey on vulnerable young women with impunity. The mechanisms of entrenched power and intimidation that enable him are exposed most clearly in a chilling 10-minute scene that sees Julia Garner’s tentative whistleblower, Jane, bringing her concerns about her boss’s nubile new hire to human resources. Stuffing down her own apprehension, she relays the scant details giving her a bad feeling to HR rep Wilcock (Matthew Macfadyen, covering a moral black hole with shit-eating corporate politeness, just as he does on ), who then affirms all her worst fears about speaking out. Incredulously repeating her own words with business-casual menace like the voice of doubt in her head, he silences and belittles and condescends and threatens in such a studied manner that we realize he’s doing his actual job: He’s there to protect the company, specifically at the expense of its employees. And his parting words, that Jane needn’t worry because she’s “not his type,” are the coup de grâce of this grueling gaslighting session. [Charles Bramesco]

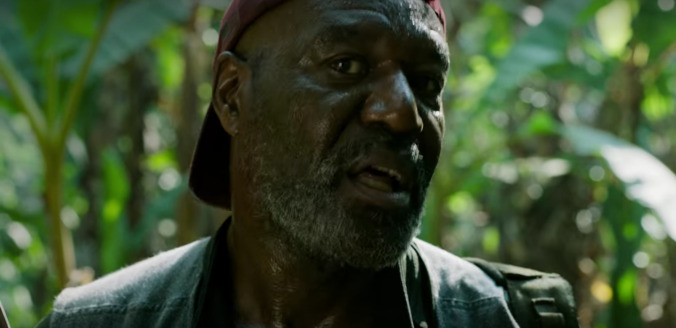

In Da 5 Bloods, Spike Lee employs every visual tool in his kit to provide his story of four aging Vietnam veterans embarking on one last mission the scope it deserves. Yet the film’s best scene is also its most straightforward, with Lee simply creating space for a killer performance. Delroy Lindo’s career-best turn as the embittered, PTSD-afflicted Paul reaches a fever pitch when he finally breaks off from the group and enters the jungle alone, with only his share of the gold and his guilt for company. Lee keeps the camera inches away from Lindo’s face as he passionately rants about the indignities he’s suffered, never breaking our gaze. The scene feels especially raw not because Lee films it in one take but because he’s clued into the unpredictable rhythms of a private, vulnerable moment with a man who has nothing left to lose. “Hear me,” Paul pleads, and Lee obliges, maintaining focus on Lindo’s weathered expression right up until the moment he pans over to his raised fist. [Vikram Murthi]

It’s hard to envision a more appropriate location for a climactic Harley Quinn fight scene than an abandoned funhouse—and the action sequence in the final act of Birds Of Prey does not disappoint. For a full 4 minutes and 45 seconds, the film’s heroines—Harley Quinn (Margot Robbie), Renee Montoya (Rosie Perez), Black Canary (Jurnee Smollett), Huntress (Mary Elizabeth Winstead), and Cassandra Cain (Ella Jay Basco)—dodge and duke it out with a team of masked henchmen, all without forsaking the comedic winks Harley and co. have been offering throughout the rest of the film. Where else can you see Rosie Perez yelp as she careens down a spiral slide, a gun in one hand and gold-plated brass knuckles in the other? [Patrick Gomez]

Russian director Kantemir Balagov’s post-WWII drama hinges on a tragedy so sudden and accidental, it takes a few seconds for the audience to realize what’s happening. It starts as a warm, intimate respite from the horrors of the Leningrad hospital where most of the film takes place, as nurse Iya (Viktoria Miroshnichenko) plays with a giggling infant in her room. But then Iya, who suffers from seizures after sustaining a brain injury in the war, stiffens up and falls onto the boy’s tiny body, pinning him to the floor. The boy cries, struggles, and—after seconds that feel like hours—eventually stops moving. Balagov’s manipulation of tone is masterful, stretching the tension in the scene so tight that the shift from playful to horrifying happens almost imperceptibly. In a film where one person gently stroking another’s hair lands like a punch in the teeth, the literal smothering of its title character’s greatest joy is par for the course—and a catalyst for more tragedy and twisted drama to come. [Katie Rife]

Orson Welles’ observation that a Hollywood movie is the biggest electric train set a boy could wish for is borne out by Christopher Nolan’s sci-fi genre collage. Dopey and narratively incoherent, the 70mm spectacle of Tenet is nonetheless filled with surreal, energetic set pieces that outpace Nolan’s usual pop cerebralism, revealing what many have suspected all along: The guy loves to blow up planes! The destruction of an actual 747 is but one of the toy-box ingredients of the film’s airport-set pièce de résistance, which also throws in a convoluted caper and backwards hand-to-hand combat, and (spoiler alert!) only gets more entertaining when the heroes make their way through the entire sequence in reverse later in the film. As an action director, Nolan has come a long way since the 2000s, and this twofer offers one of the giddiest stretches in his filmography. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

In Clea DuVall’s frustrating romantic comedy, Kristen Stewart’s Abby spends the holidays at the family home of her girlfriend, Harper (Mackenzie Davis), who insists they both pose as straight while they’re there. (Meanwhile, Harper’s ex, Riley, a smoldering Aubrey Plaza, is right there.) Toward the end of the movie, Abby has finally had enough of Harper’s duplicity, leading to Happiest Season’s best scene. Dan Levy, transcending his funny best-friend role as John, explains to Abby that everyone’s coming-out story is different: “Harper not coming out to her parents has nothing to do with you.” He painfully describes the terrifying moment right before the words “I’m gay” are spoken aloud, knowing that nothing will be the same afterward. John’s speech offers poignant insight into the coming-out experience, making a better case for Harper’s behavior than she ever does herself. (But still: Riley! Come on.) [Gwen Ihnat]

A worthy successor to Edgar Wright’s , Extra Ordinary is the sweetest comedy of the year to feature multiple ectoplasm belches. Set in small-town Ireland, the supernatural comedy follows reluctant ghostbuster Rose Dooley (Maeve Higgins) as she aids widower Martin Martin (Barry Ward) with his possessed-teenage-daughter problem, further complicated by one-hit-wonder-turned-satanist Christian Winter (Will Forte), who aims to make said daughter his virgin sacrifice to the demon Astaroth. Like any good farce, Extra Ordinary eventually brings its cast together under one roof; when our heroes arrive to Winter’s manse too late to stop the sacrifice, Astaroth emerges from the pit of hell pissed—that was no virgin, you see. To say more would ruin the madcap surprises of the culminating scene, but it’s a marvel, juggling high- and lowbrow humor with ease and underscoring the importance of a well-executed climax, literally and figuratively speaking. [Cameron Scheetz]

No one listens to Autumn (Sidney Flanigan) in Eliza Hittman’s devastating Never Rarely Sometimes Always. Not the school bullies, not her mom’s lecherous boyfriend, and not her coercive boss. It’s only after an Odyssean journey lands her in Manhattan’s Margaret Sanger Clinic that the pregnant teen is treated with any kindness, questioned by an empathetic case manager (played by real-life counselor Kelly Chapman) before scheduling an abortion. Hittman stays on Flanigan’s face during the interview, her subtly shifting expressions communicating the difficulty of sharing her trauma as she answers “never,” “rarely,” “sometimes,” or “always” to a series of questions about her sexual history. This is Autumn at her most vulnerable, but for the counselor, who’s well-acquainted with the pandemic of domestic and sexual violence that affects so many women, it’s just another day at work. In that balance, this timely and enraging film captures the ways Roe V. Wade has been undermined and unfulfilled since 1973. [Roxana Hadadi]

Full of playful flourishes and time-bending gambits, Michael Almereyda’s stylish subversion of the conventional biopic gives electricity pioneer Nikola Tesla his moment in the limelight. Tracing the inventor’s rise and fall, Tesla ends on a necessarily tragic note as our hero’s freewheeling genius comes under scrutiny and skepticism, and he’s cast away by the modern world he helped bring into being. Against a dreamy sunset backdrop, Ethan Hawke’s terse but intriguingly vulnerable Tesla grabs a mic and launches into a droning karaoke rendition of Tears For Fears’ ’80s pop classic, “Everybody Wants To Rule The World.” The anachronistic send-off is Tesla’s gushing final act, a lyrical expression of anguish, and perhaps regret, before the curtain falls. “So glad we’ve almost made it,” he croons. “So sad they had to fade it.” [Beatrice Loayza]

Taken out of context, the last four minutes of Thomas Vinterberg’s Another Round could be mistaken for a big-budget ad for a luxury spirits brand: Mads Mikkelsen, exuding dignity and sophistication in a well-tailored suit, cavorts around a Danish pier to the tune of Scarlet Pleasure’s “What A Life.” He sips from random bottles and cans proffered by cheering teenagers in white, showing off some pretty impressive dance moves (Mikkelsen, like his character in the film, used to be a professional dancer) as he gives in to the moment. He then leaps into the harbor, and the camera captures his long-legged tumble in freeze frame. It’s a vital, life-affirming sequence, and one that’s only slightly tempered by the fact that, in the movie, Mikkelsen and his friends have just come from the funeral of an ex-colleague who died from complications of alcoholism. That makes this celebratory ending just slightly bittersweet—and the perfect punctuation on Vinterberg’s even-handed and honest look at humanity’s relationship with alcohol. [Katie Rife]

Lots of horror movies end with the revelation that the monster isn’t really dead, that it will return to wreak more havoc. Relic, a horror movie so blatantly about the horror of losing a loved one to dementia that it basically has no subtext to speak of, puts a haunting spin on that sequel-teasing genre tradition. After a final act of shrieking haunted-house mayhem, Kay (Emily Mortimer) returns to comfort the “monster” she’s finally escaped: her elderly mother, Edna (Robyn Nevin), who’s been possessed by a dark supernatural force that’s really just a metaphor for her mental deterioration. Tenderly peeling off the last of the old woman’s skin to reveal her final form, Kay and her own daughter, Sam (Bella Heathcote), cradle the withered, harmless creature beneath. It’s a deeply moving end to this family’s nightmare. And then Sam sees the small black spot on her mother’s neck—a discovery as ominous as bubbles rising to the surface of Crystal Lake or a striped car cruising down Elm Street. [A.A. Dowd]

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.