The best movies on Showtime

The best picks available on the premium cable channel's streaming service

Streaming libraries expand and contract. Algorithms are imperfect. Those damn thumbnail images are always changing. But you know what you can always rely on? The expert opinions and knowledgeable commentary of The A.V. Club. That’s why we’re scouring both the menus of the most popular services and our own archives to bring you these guides to the best viewing options, broken down by streamer, medium, and genre. Want to know why we’re so keen on a particular title? Click the author’s name at the end of each entry for some in-depth coverage of the film from The A.V. Club’s past.

All the films listed are available on demand via Showtime or streaming on their website. And be sure to check back often, because we’ll be adding more recommendations as films come and go.

Looking for other movies to stream? Also check out our list of the best movies on HBO Max, the best movies on Amazon Prime, best movies on Netflix, best movies on Disney+, and best movies on Hulu.

This list was most recently updated Sept. 27, 2020.

Historically, science-fiction films have come in two varieties: one driven by ideas, the other by gadgets, gimmicks, and bug-eyed monsters. The former type has mostly been in retreat for years, if not since its apotheosis, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. But A.I.—a realization of a long-discussed, never-realized Kubrick project, written and directed by Steven Spielberg—has enough ideas to make up for the extended shortage. Working with wild ambition that occasionally (and inevitably) overwhelms itself, Spielberg launches an inquiry into humanity itself, its origins, its nature, and its end. His vehicle is a robotic boy created by scientist William Hurt and played by Haley Joel Osment, a machine that, unlike any before him, comes programmed to love his adoptive parents. Kubrick would have made a different film, but discussing the hows and wherefores is as pointless as debating whether his version would have been better. Spielberg’s best tribute to 2001's director is this: With A.I., he has created what history should confirm as one of the defining films of its time, a compelling, moving inquiry into the most basic elements of existence, told with fear and awe in a vocabulary exclusive to moviemaking. []

A towering symbol not just for the world of boxing, but for the world at large, Muhammad Ali isn’t anyone’s idea of an everyday boxer, but director Michael Mann’s skills are put to good use as he attempts to get behind the symbol in the new biopic Ali. Dramatizing the eventful decade between two upsets that won Ali heavyweight titles—his first encounter with Sonny Liston in 1964 and the Rumble In The Jungle with George Foreman in 1974—the film employs an episodic structure that focuses on key phases of his development, showing him as a brash young fighter, a spokesman for Black Power, a legal martyr for his refusal to be drafted for Vietnam, and an international icon. Will Smith plays Ali, and while the choice might seem odd, it proves inspired. Mann’s Ali, like its subject in his prime, seems incapable of making a false move. []

From its opening scene, Amy is almost more noteworthy for what it doesn’t do as a documentary than for the sad story of its famous subject. Director Asif Kapadia () opens his film not with a montage of talking heads spouting money quotes about Amy Winehouse, but with a home movie of teenage Winehouse hanging out with friends for someone’s birthday. A few of them begin tunelessly singing “Happy Birthday To You,” their voices fading when an off-camera Winehouse finishes the song with the kind of overstated flair possessed by someone who likes showing off her knockout pipes. []

reteams with his stars for this funky little cult-movie-in-the-making by his friend and writing partner Joe Cornish. (Naturally, the two worked on Spielberg’s new Tintin movie, which co-stars Pegg and Frost.) Continuing their extraterrestrial theme, the film concerns a motley, multicultural crew of street kids who take on monsters from outer space. In a pre-Star Wars performance, John Boyega plays a charismatic gang leader whose attempts to mug a pretty nurse played by Venus’ Jodie Whittaker are rudely interrupted by the unexpected appearance of a fearsome alien monster. Whittaker, Boyega, and Boyega’s gang must subsequently put aside their gender, racial, and class differences for the sake of a common cause: fighting off a mysterious alien plague. Frost is funny as a low-level drug dealer and National Geographic buff, as is Luke Treadaway as a student who stops by Frost’s weed spot to pick up some marijuana, and gets more than he bargained for. []

As strange as it may seem, an entire subgenre of black film can be traced to Joel Schumacher, the flashy hack behind such high-gloss, low-substance, whitebread fare as St. Elmo’s Fire and Batman & Robin. Schumacher wrote the screenplay for 1976's delightful Car Wash, which became the template for 1995's Friday and last year’s abysmal semi-remake The Wash. Like those films, Barbershop borrows Car Wash’s 24-hour timeframe, brassy ensemble cast, and prominent soundtrack. But where lesser Car Wash progeny only incorporate their predecessor’s most obvious elements, Barbershop replicates the intangible qualities that made it special: its sunny spirit, stellar supporting cast, and surprising sociological savvy. Barbershop tackles serious issues (assimilation, reparations, class conflict) without reducing its characters to mouthpieces for differing viewpoints. Much of the credit belongs to the director, music-video veteran Tim Story, who does a terrific job juggling multiple subplots and a sprawling, uniformly fine cast while maintaining a breezy pace. []

Writer-director Whit Stillman’s best overall film, 1994's Barcelona, stars Stillman regulars Taylor Nichols and Chris Eigeman as cousins with confusingly similar names (Ted and Fred), but opposed personalities. Nichols is an American salesman stationed in Spain in the early ’80s, and Eigeman plays a Navy officer who stays with his cousin while on a PR mission. The boys hook up with a couple of local women (Mira Sorvino and Tushka Bergen), but while Barcelona is grounded in a common romantic-comedy plot, Stillman adds a genteel inquiry into the respective meanings of beauty and image, keenly examining how cultures clash in ways both subtle and resounding. []

Though many years and straight-to-video Shannon Tweed knockoffs have passed, Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct retains a special allure, one that can be attributed in large part to the uncrossing of Sharon Stone’s legs. Granted, there’s much more to the movie than that notorious interrogation scene, but no better example of the film’s unique mix of vulgarity and elegance, which brought Old Hollywood into a world of trashy explicitness. Sitting with her blond hair pinned back like Kim Novak—one of several nods to Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo—Stone carries herself with the supreme self-confidence of a classic femme fatale, yet her candor is unquestionably modern, liberated from more than just undergarments. Unapologetically sexual, as free as a man to pursue her appetites, Stone’s character became an instant post-feminist icon, even though she’s a diabolical sociopath. []

Much as with Holocaust movies, it occasionally seems like there are no new ways to approach the story of Mexican immigrants illegally working in America. Undocumented workers are a contentious subject, and films about them tend to follow established lines of compromise, acknowledging that they’re breaking laws, then compensating by framing them as longsuffering, saintly martyrs. With A Better Life, director Chris Weitz and screenwriter Eric Eason find a new filter for those familiar signifiers by essentially remaking Vittorio De Sica’s 1948 classic Bicycle Thieves. In the process, they drop a lot of De Sica’s neo-realist focus on detail, while losing none of the strong performances or heartbreaking suffering. Demián Bichir stars as an overburdened single father working as a landscaper in east L.A., struggling to support his teenage son (José Julián), a troubled boy close to falling in with the local gangs. []

Demographically savvy in its mixture of scatological gags, gentle romantic comedy, and crowd-pleasing sentimentality, Big Daddy is Adam Sandler’s best movie, a surprisingly touching and consistent comedy that finds him reaching out to new audiences without abandoning the transgressive meanness that has enlivened his best work. A big part of the film’s success is derived from the chemistry between Sandler and the Sprouse twins, who make better foils than the obligatory love interests with whom the actor has been saddled in the past. Of course, Big Daddy features an obligatory love interest of its own—Joey Lauren Adams as a spunky, workaholic lawyer—but the filmmakers wisely keep the focus on the disarmingly tender relationship between Sandler and his two young co-stars. []Available Oct. 1

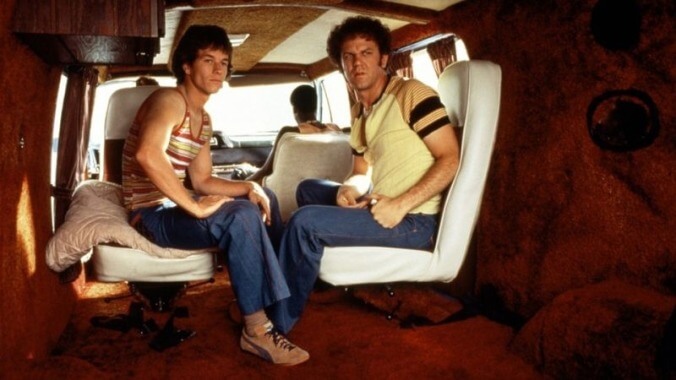

Director Paul Thomas Anderson’s second film is a sprawling, energetic, audacious look at the porn industry of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. Mark Wahlberg, in a performance that allows even “Wildside” to be forgiven, plays a young stud, with a talent clearly outlined by his tight jeans, who rises to the top of the industry only to let success go to his head. A large and universally excellent cast (Burt Reynolds, Julianne Moore, John C. Reilly, Don Cheadle, Heather Graham, William H. Macy) plays the extended family he joins. Though it’s incredibly stylish, Anderson and his cast never let Boogie Nights stray from its human center. For example, as a porn producer with artistic aspirations, Reynolds plays a character that could easily have been a caricature, but he conveys sleaze with heart so well that the threat never comes close to materializing. By taking on the porn industry, Anderson has chosen a subject that could easily be mined for cheap laughs. But while it’s very funny, Boogie Nights taps into something much deeper with its on-target depiction of the shifting political and social tides of the ‘70s and ‘80s and thoughtful relationships between characters. It’s a deeply satisfying movie. []

Based on Helen Fielding’s best-selling, acclaimed 1996 novel of the same title (it won British Book Of The Year in 1998), the highly anticipated film arrived after a decade of big-budget romantic comedies had made audiences familiar with the beats, but before their tropes had been completely solidified—something that, for better or for worse, Bridget Jones’s Diary helped to do. In fact, the movie’s trailer plays beat-for-beat like the kind of thing that Black Widow parody was mocking. Yet it’s remarkable how little its clichéd trailer does justice to the sweet, funny, empathetic spirit of the film. Bridget (Renée Zellweger) is an accident-prone 32-year-old who can’t seem to get her career, her body, or—most importantly—her love life in order. So after a particularly embarrassing start to the New Year in which she butts heads with awkward, aloof barrister Mark Darcy (Colin Firth), Bridget decides to turn her life around. She starts a diary to hold herself accountable, but it’s not long before she’s repeating old patterns and falling into bed with the “office scoundrel,” her boss Daniel Cleaver (Hugh Grant). Eventually, however, Bridget finds her confidence, while simultaneously realizing she may have misjudged Mark after all. []

Steven Spielberg and Leonardo DiCaprio both know a little something about conquering the world at a young age, which may explain why Catch Me If You Can paints such a sympathetic and resonant portrait of its wunderkind protagonist, a wily real-life con-man who passed millions of dollars worth of worthless checks and successfully impersonated a doctor, FBI agent, and airline pilot, all before turning 21. Loosely based on the self-aggrandizing autobiography of Frank Abagnale Jr., Catch Me If You Can stars DiCaprio–as effectively cast here as he was miscast in Gangs Of New York–as its debonair antihero, the quick-witted, licentious son of prominent New York businessman Christopher Walken. Bored by school and eager for new challenges after his beloved father’s traumatic divorce, DiCaprio embarks on a series of increasingly complicated and lucrative criminal endeavors. Tom Hanks co-stars as DiCaprio’s friendly antagonist and father figure, a straitlaced, dry-witted federal agent who can’t help but feel sympathy for DiCaprio’s baby-faced grifter. [Noel Murray]Available Oct. 1

More a narrative revue than a play, Chicago doesn’t immediately lend itself to a cinematic interpretation, and the conceptual difficulties kept it from the screen until now. But in his film debut, theater and TV vet Rob Marshall slashes through this Gordian knot by turning the songs into Walter Mitty-esque asides and never trying to play down the artificiality. Just as the 1995 stage revival looked to Fosse the choreographer for inspiration, Marshall looks to Fosse the film director, keeping the staging dark and the frills limited, and letting the rhythm of the music and the dancing drive the rhythm of the editing. Realized with flair and confidence belying the fact that—apart from the more determinedly experimental Moulin Rouge and Dancer In The Dark—this is the first high-profile musical in some years, Chicago’s musical numbers could stand on their own even if the compelling story didn’t sweep them along. []

Bound and hooded by a group of activists-turned-terrorists-trying-to-turn-activists-again, a kidnapped Clive Owen sits in a shelter papered in a decade’s worth of tabloid headlines. They scream of war, nuclear mishaps, and ecological disaster. It’s real end-of-the-world stuff, presented in the form of everyday material, much like the film around it. There’s much more to Alfonso Cuarón’s Children Of Men, adapted from a P.D. James novel, than a tour of a world gone terribly wrong, but the story comes tightly bound to its intricately realized setting, a fascist Britain that’s also apparently the last nightmarish refuge of civilization. As a former radical now whiling away his time drinking scotch and manning a desk in a low-level bureaucratic office, Owen seems content to watch the world go to hell, until his ex-wife (Julianne Moore), a leader of the pro-immigrant Fishes, presses him into retrieving a pair of illegal travel passes in the hopes of reaching a group of much-rumored, never-confirmed benevolent off-shore scientists called The Human Project. Their motives, tied to the well-being of a young immigrant (Claire-Hope Ashitey), will soon become clear, but only after the cost of failure has been made equally clear. []

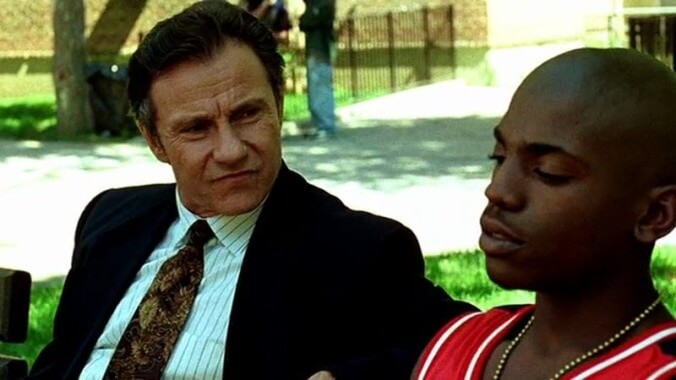

The first half of the ’90s saw a proliferation of dramas about inner-city crime, but Spike Lee took his time before jumping into that fray with Clockers, a Richard Price adaptation that debuted to some acclaim and little box office in 1995. True to Lee’s ongoing portrait of Brooklyn, the movie seems more interested in the neighborhood it portrays than the specifics of the drug trade. Much of it is seen through the eyes of Ronald (Mekhi Phifer), also known as “Strike,” a low-level employee of Rodney Little (Delroy Lindo), a local shopkeeper who fancies himself both a father figure and, when needed, fearsome boss in charge of many of the neighborhood’s young black men. Strike spends most of his time dealing from park benches, nursing a developing ulcer, and early in the film, Rodney tells him that he can move up the chain if he takes care of a rival. Soon enough, that man is dead. But the murder isn’t shown on-screen, and a question lingers over both the audience and detective Rocco Klein (Harvey Keitel): Was Strike actually responsible for this man’s death? []Available Oct. 1

Mike Nichols’ uneven filmography has won praise for its maturity and tastefulness, but the titles are rarely less than ingratiating, and have never approached the daring provocation of his early work. So it’s a pleasant surprise that his new Closer, a lacerating four-character suite on the elusiveness of love and intimacy, finds Nichols returning to his roots without having lost his sardonic edge. “The heart is a fist wrapped in blood,” deadpans Clive Owen, who plays the most Darwinian of romantic aggressors, though not necessarily the most devious. It’s a stretch to say that Closer chronicles four misguided quests for happiness—or that any of the people involved are even capable of being happy—but they’re just vulnerable enough to hurt each other. The film opens with the impossibly romantic image of two lonely faces connecting in a crowd, but an accident breaks the spell: After fleeing a bad relationship all the way to London, free-spirited American Natalie Portman almost literally falls into Jude Law’s arms when she’s clipped by a cabbie on the left side of the road. Their fateful encounter blossoms into an affair that inspires Law, who writes obituaries (“the Siberia of journalism”), to write a novel. A year later, Law gets a book-jacket photo snapped by Julia Roberts, an older and more experienced woman who immediately seizes his interest. The love triangle turns into a square when Law draws Owen into an Internet sex chat-room and unwittingly arranges for him to meet Roberts, who later agrees to marry him. []

The secret-shrouded brainchild of producer J.J. Abrams, writer Drew Goddard, and director Matt Reeves, Cloverfield speaks so directly to a decade in which camera phones and YouTube have take the middleman out of video. The film taps into the spirit of the age in other, more unsettling ways as well. Its horror is devastating and citywide. Baffled news anchors report it breathlessly, inspiring panic in characters who realize that the violence that only happens elsewhere has found its way home. The monstrous source of the violence maintains an unerring concentration on destruction, and spawns other, smaller monsters with the same focus. It leaves terror, broken buildings, and clouds of dust behind. The best efforts of conventional warfare can’t bring it down. The filmmakers have gone to great lengths to keep the nature of the threat a secret, so let’s just say that it couldn’t have existed without H.P. Lovecraft, H.R. Giger, or Ishirô Honda, the director who gave Japan an embodiment of its then-recent nuclear attacks with Godzilla. Also, it’s absolutely terrifying, and it’s all the more effective for the way it lets viewers spend time getting to know the terrified stars, and the emotions and regrets behind their seemingly futile efforts to survive. It puts human faces on the victims of mass destruction, faces that might easily have been yours or mine, staring down the maw of something we don’t understand. []

Courage Under Fire opens with the kind of tasteful battlefield bombast often associated with director Edward Zwick, as Lieutenant Colonel Nathaniel Serling (Denzel Washington) commands a tank during the first Gulf War. But after a disastrous friendly fire incident, Serling returns Stateside; his blunder is covered up, and he’s assigned to determine whether another soldier, Captain Karen Walden (Meg Ryan), should receive a posthumous Medal Of Honor. The movie ostensibly focuses on what happened to Walden and her men as Serling starts to notice inconsistencies in the survivors’ stories, and much of the buzz around its 1996 release similarly emphasized Ryan, the romantic comedy queen, in a grittier and more dramatic role. But the true center of the movie is Serling, beautifully played by Washington. []Available Oct. 1

D.B. Sweeney and Moira Kelly star as two world-class athletes whose Olympic dreams are deferred by an eye injury and stubbornness, respectively. Hockey player Doug (Sweeney) must alter course on his way to the gold, trading in his helmet for sparkly shirts to become Kate’s (Kelly) figure-skating partner. She’s imperious, he’s affable, so there’s no way they can work together, right? Of course, the pertinent rule of attraction dictates that these opposites will fall in love despite their differences. It’s a stale premise made fresh by Sweeney’s hangdog charm and Kelly’s vulnerability. [Danette Chavez]

Based on James Dickey’s novel, John Boorman’s 1972 thriller follows four city slickers from Atlanta as they take a canoe trip down the Cahulawassee River, a fictional waterway in the hill country of North Georgia. This will be the last time the river will be a river and the local village will be the local village: A dam under construction will soon flood both out of existence, and uproot the townspeople, taking an entire way of life with it. Boorman lingers on shots of bulldozers moving dirt around these vast unnatural canyons, and he lingers later on the local church, the symbol of bedrock moral and spiritual value, getting carried off on the back of a flatbed. For the locals, the presence of these outsiders, paddling merrily down the Cahulawassee one last time before it’s obliterated, must feel like the final insult. And, in one of the most notorious scenes in American cinema, they make them pay for it. []

On its surface, Desert Hearts doesn’t seem like such a groundbreaking film. It’s the opposite of flashy—a quiet, intimate portrait of love blossoming between two women against a rocky Reno backdrop. But in 1985, it was revolutionary just to make a lesbian romance the center of a film—especially one that did not end in tragedy. In Desert Hearts, based on a novel by Jane Rule, the relationship between Vivian and Cay is the primary focus of the movie, offering a new landscape for cinema to explore. Vivian Bell (Helen Shaver) is a stuffy English literature professor from Columbia University who wants to dissolve her loveless marriage. She takes up residency at the ranch of Frances Parker (Three’s Company sitcom star Audra Lindley, the biggest name in the cast), a warm, down-to-earth woman who claims that out in “God’s backyard,” Vivian will enjoy “lots of iced tea and no deep thinking.” But Vivian’s desert respite is soon rocked by Frances’ sort-of daughter, Cay (Patricia Charbonneau, in her film debut), a coltish free spirit who is upfront about her attraction to and relationships with women. To Vivian, Cay represents all the things she isn’t—confident, unrepressed, free to be herself—which makes her all the more attractive to someone who’s still searching for answers. []

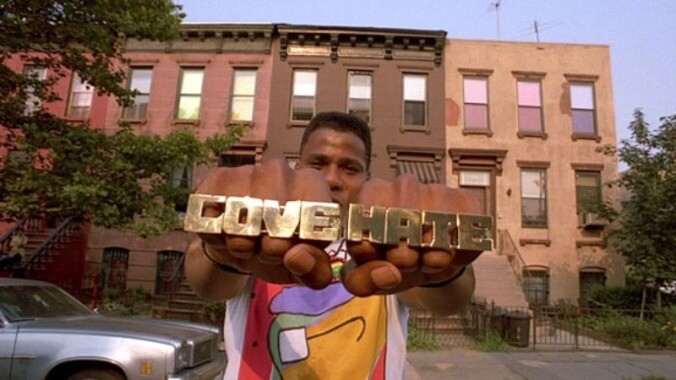

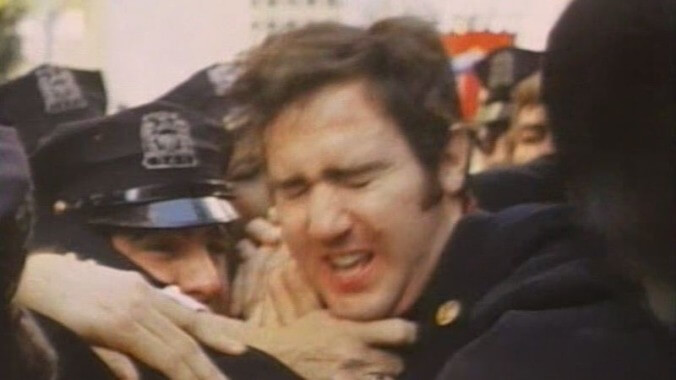

Released during one of New York’s most hotly contested mayoral elections, as well as one of the hottest summers on record, 1989's Do The Right Thing prompted a controversy that threatened to overshadow its artistic worth. But neither those initial criticisms nor the muddled politics of many of Lee’s later films lessen the impact or importance of his brilliantly constructed breakthrough. Following the day-in-the-life-of-a-community paradigm popularized by American Graffiti and Car Wash, Do The Right Thing focuses on one exceedingly hot day in the life of Brooklyn’s Bed-Stuy neighborhood, a primarily black community enduring an uncomfortable codependence with its primarily non-black shop owners. Danny Aiello and Spike Lee lead a large, excellent cast as an Italian-American pizza-store owner and his delivery boy, respectively. At the time of its release, Do The Right Thing was attacked for allegedly painting a hopelessly bleak view of American race relations. But the film’s supposed nihilism isn’t as striking as its warm, empathetic depiction of a community wracked with poverty, aimlessness, and misdirected anger, yet still bursting with vitality and solidarity. Rather than peddling false uplift, the trademark of Hollywood dramas about racism, Lee’s film depicts a universe where the social strictures designed to maintain order are forever endangered by an underclass no longer willing to work within a system that has failed them. []Available Oct. 1

Brian De Palma’s Dressed To Kill features a schizophrenic psychiatrist as its villain. That counts as a spoiler, but it’s probably fair to say that the statute of limitations on surprises has run out after 35 years. Besides, it’s not as if the film really tries to disguise its big twist. No sooner have we met the prosperous Manhattan headshrinker Dr. Robert Elliott (Michael Caine) than De Palma’s camera calls attention to the little mirror sitting on his desk; it doesn’t take an advanced degree in psychology (or cinema studies) to detect the split personality symbolism. Just as Dr. Elliott skillfully disguises his essential depravity underneath a veneer of intellectual respectability (and puts on a blond wig and a black trench coat when he’s on the prowl), Dressed To Kill is a giallo disguised as a metropolitan, mainstream thriller. It’s a film of impeccable pastel surfaces concealing a deep red, blood-drenched core. At this point, explaining the film’s relationship to Psycho is as prosaic and academic a task as, well, the psychiatrist’s explanation at the end of Pyscho—a scene De Palma gleefully parodies twice over in his final act. But it’s worth pointing out that where Hitchcock’s classic deconstructed Norman Bates’ psychological architecture as an afterthought, Dressed To Kill is explicit about duality at every level of its storytelling. []

Voracious readers of the late David Foster Wallace, an author of massively ambitious fiction and casually revealing nonfiction, could be forgiven for regarding a movie about his life with some skepticism. How, after all, could one normal-sized film hope to capture the spirit and legacy of a writer who many came to regard as a voice of his generation? Wouldn’t any attempt to get into his famously bandana-wrapped head feel insufficient, at least compared to the sheer volume of work Wallace himself produced on the subject? But that’s the gentle genius of The End Of The Tour, James Ponsoldt’s witty and poignant new gabfest. Not only does the film productively narrow its time frame, dramatizing just five days in the life of the revered wordsmith, it also unfolds from an outside perspective—that of the reporter who accompanied Wallace on the final leg of the Infinite Jest book tour. The result is less portrait of an artist than snapshot of a brief, meaningful encounter, shared between two men enjoying different stages of professional success. That one of these men happens to be a modern literary hero is almost, if not quite, incidental. []

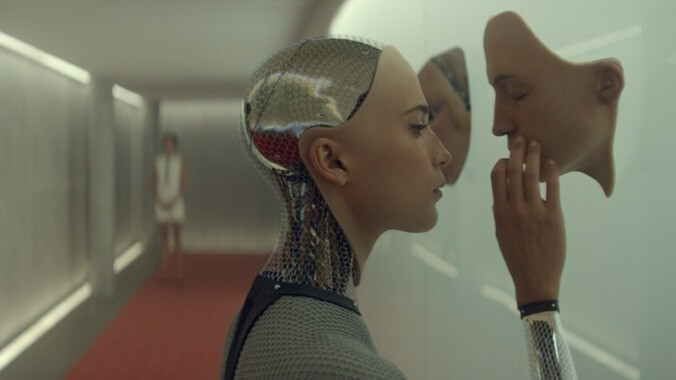

Make no mistake, this is a film of ideas—sadder, quieter, more delicate than the Hollywood sci-fi standard—where every sliding wall of opaque glass suggests something about technology and the way people would use it. The AI, Ava (Alicia Vikander) is specifically gendered, but so is everything else in the film, from the friendship and tension that develops between the two men to Caleb’s (Domhnall Gleeson) unconcealed attraction to this demure robot, who lives in a little glass box with a closet full of floral print sundresses. In both his screenplays and his prose, director Alex Garland often focuses on makeshift societies; here, he creates a tiny one, limited to a few rooms and hallways, but with a future of infinite technological possibilities. As is often the case, it can’t fully let go of the world it’s supposed to replace. []

Loved and revered perhaps more fiercely than any other non-commercial filmmaker of his time, Stanley Kubrick was a true iconoclast, a cinematic rebel who could command as much artistic control as any other major director. And, perhaps more than his other films, Eyes Wide Shut epitomizes Kubrick’s commendable and audacious willingness to venture into unexplored territory and risk making a fool of himself. Like Crash and Blue Velvet, two similarly fearless, sexually transgressive but ultimately moralistic films that straddled the fine line between genius and lunacy, Eyes Wide Shut is above all a masterpiece of sustained tone, a tightrope act that pays off in rich and unexpected ways. []

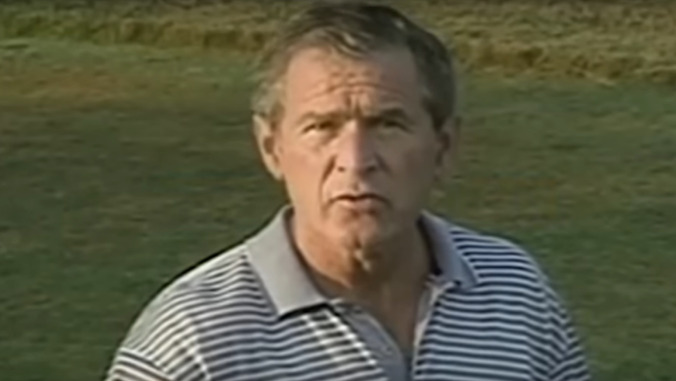

One of the most striking things about watching now is realizing just how deeply, uncomfortably resonant it is with our current state of the union. Within the first half hour, it depicts a venal, intellectually bankrupt administration led by a preening dimwit as he spends most of his time in the White House golfing and avoiding responsibility. And then—even more timely—the film depicts the American president actively impeding the cause of justice by trying to prevent the House Of Representatives or independent commissions from setting up probes to investigate the links between his own checkered past and avowed enemies of American democracy that might not-so-secretly hold a little too much sway over him. Sound familiar? []

Pairing director Terry Gilliam and star Robin Williams seems like a recipe for unbridled id, like letting the flying head Williams briefly played in run amok for two hours. But The Fisher King brings out the best in both artists. Jeff Bridges has the straighter role in this buddy comedy. He plays Jack, a shock-jock whose cavalier remarks convince a listener to commit mass murder. Three years after this incident, he’s marinating in self-pity, loathing, and booze; mistaken for a homeless man on the streets of New York, Jack meets Parry (Williams), an actual vagrant with a connection to his past. Back in 1991, surely some grumbled that the showier Williams performance received an Oscar nomination, while Bridges was relegated to the sidelines for more subtle work. (Call it the Tom Cruise-in-Rain Man non-award). But both actors are terrific in The Fisher King, as are Mercedes Ruehl as Jack’s patient but blunt-spoken girlfriend and Amanda Plummer as a mousy woman Parry admires from afar. The movie finds beauty in a setup as simple as the four of them sitting in a booth at a Chinese restaurant, and even a quest for the Holy Grail turns intimate. Williams modulates his performance accordingly; despite his outbursts, he never goes over the top. Against the odds, he and Gilliam ground each other. []

Fly Away Home has been marketed as an innocuously cheerful bit of high-concept family fluff: Geese meet girl, geese follow girl, girl and geese fly over pretty landscapes and past corporate office building. In fact, Fly Away Home does make good family fare, but not because of the tepidness often associated with that label: It’s wholesome without being shallow. Anna Paquin and Jeff Daniels both establish great screen presences; Paquin is a New Zealand girl whose mother is killed during the opening credits, and Daniels is her long-absent but cool, Boho-liberal-inventor father who brings her back to his farm in rural Ontario. Paquin is particularly good, playing a more conventional character than in The Piano, but bringing depth to her early scenes of grief and depression. Surprisingly, she achieves moments of transcendent beauty with her geese long before any of them leave the ground. What doesn’t work as well are the transitions between these moods: Needless obstacles include a villainous game warden; about a reel’s worth of laborious and humorless planning of a trip south; and an inappropriately cute shower disaster scene that seems like an attempt to lighten the mood, but which instead serves to trivialize the fear and pain Paquin’s character feels. All this is forgettable, but also forgivable given the moments of genuine emotional connection throughout. []

Some of the most chilling visuals in Fright Night—a new remake of Tom Holland’s well-liked, self-aware 1985 vampire movie—come not when the blood starts spurting and the stakes start flying, but from the images of a desolate suburban oasis that appear near the opening of the film. Just a few uniform blocks surrounded by desert, darkness, and the distant lights of Las Vegas, the setting suggests a nice, normal place where unspeakable things could transpire without the world at large noticing—and where those directly affected might be too dulled by the blanketing blandness to save themselves. That’s more or less what happens when a nice high-school kid (Anton Yelchin) fails to suspect that his new next-door neighbor (Colin Farrell) might be the reason so many fellow students have stopped showing up for school in the morning. To be fair, he has his reasons for not noticing. Too distracted by the pressure of dating a classmate (Imogen Poots) above his social station, Yelchin ignores the warnings of his one-time best friend Christopher Mintz-Plasse, an unrepentant nerd who’s had his eye on Farrell for a while and has come to a chilling conclusion: “He’s the fucking shark from Jaws.” Trouble is, Farrell has had his eye out, too. []

In the early ’80s, The Go-Go’s were the epitome of bright, breezy fun-girl pop, cresting the first wave of MTV stardom. But the true story of the band is much darker, awash in depression, drug addiction, and intra-band squabbles that belied the group’s candy-colored façade. Documentarian Alison Ellwood continues her encyclopedic efforts to chronicle the California music scene (following History Of The Eagles and Laurel Canyon) with a new Showtime documentary on the first all-girl band in the U.S. to have a No. 1 record playing its own instruments and writing its own songs. As one member of the band says in the movie’s intro, “People automatically assume that we were put together by some guy, but we did it all ourselves.” The story Ellwood puts together is both straightforward and familiar, traveling from the band’s scrappy beginnings to the pitfalls of fame that would inevitably become its undoing. []

B-movie maverick Larry Cohen (It’s Alive) spent much of the ’70s and ’80s blending elements of science fiction, horror, and the police procedural into idiosyncratic schlock. But God Told Me To may be his most bonkers creation, a crime thriller that gets more outlandish the deeper its hero gets into his investigation. Cult connoisseurs will be in heaven, but the film has more to offer than transgressive weirdness. Cohen, who writes more often than he directs these days, had a real knack for capturing the flavor of the city. This is a great New York film, full of seedy scenery and populated by a stable of eccentric bit players. (Andy Kaufman, in his first big-screen appearance, plays a cop who goes berserk during a parade.) Ambitious in scale despite its modest budget, God Told Me To also established Cohen’s talent for getting a lot of bang for his limited buck. As a film about faith, it’s pure hooey, but it’s hooey with a provocative edge. What could be scarier, Cohen asks, than the dawning realization that the voices in the heads of the deranged are all coming from the same divine source? And he’s a got a plan for you, too. []

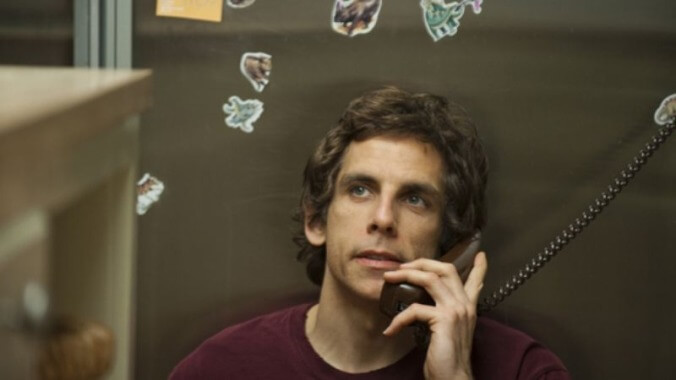

In Greenberg—the 2010 caustic character study from writer-director Noah Baumbach—mumblecore darling Greta Gerwig plays a rudderless 26-year-old whose overarching philosophy involves taking the path of least resistance. Gerwig toils as a nanny for a wealthy Southern California family, halfheartedly pursues a singing career, and stumbles into bed with men she barely knows because wordlessly cooperating is often easier than saying no. Into her inert, apathetic life comes Ben Stiller, her employer’s black-sheep brother and housesitter, an emotionally fragile recent graduate of a mental hospital engaged in a passive-aggressive, decades-long battle with the compromises and vulgarity of the modern world. Like Jeff Daniels in Baumbach’s The Squid And The Whale, Stiller is intent on rejecting a world he feels, not without reason, has rejected him. Stiller’s bitter loner seems to have stopped developing emotionally when his future radiated the most promise. When he was 25, major labels wooed his band, but he got spooked and has wrestled with the consequences of his actions ever since. Stiller claims he’s devoting himself to doing nothing, but his lack of ambition comes across not as a Zen state of contentment, but as the self-serving rationale of someone who has given up. Gerwig thinks she can reach the sensitive soul buried under layers of bitterness, rage, and self-destruction, but Stiller doesn’t want to be saved: He can’t take a step forward without shimmying three or four steps back. His brittle exterior might just mask an even angrier, even more dysfunctional interior. []Available Oct. 16

Few movie soundtracks have changed the face of popular music more than the one for The Harder They Come, which single-handedly put reggae on the map, paving the way for Bob Marley’s breakthrough album a year later. But while the distinct island sounds remain forever lodged in the public consciousness, it would be a shame to forget the corrosive and politically radical vehicle that brought them there. Like Burn! and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song before it, The Harder They Come is a crude, low-budget expression of revolutionary values, with an outlaw hero—the people’s hero—taking on his oppressors with guns blazing. Billed as “Jamaica’s very first feature-length film,” it shouldered the heavy responsibility of introducing the country to the world, but writer-director Perry Henzell’s approach is simple and organic, building a sense of national identity that keeps perfect time with the music. In an iconic turn, singer-songwriter Jimmy Cliff stars as a country naïf who arrives in Kingston with little money and no prospects, determined to be a famous musician. Once there, he faces with corruption at every turn, from a monopolistic producer who will only pay him $20 a song to a missionary church that peddles “The Word,” to a police force bought off by the criminal element. Desperation tempts him to the ganja trade, and he finally achieves notoriety by shooting a few cops in self-defense and hiding in the Underground; meanwhile, his single climbs to the top of the charts. Layered with biting ironies, Henzell’s story lands forceful blows to the capital-A Authority that poisons just about every social and religious institution in the city. []

Dorothy (Constance Wu) makes her living as an exotic dancer, climbing into the laps of Wall Street types and seducing them into buying plenty of drinks—and leaving plenty of tips—under her alias of Destiny. But Hustlers writer-director Lorene Scafaria is interested in a different sort of intimacy: Her camera seems to capture just about every time Destiny touches hands with her more experienced co-worker Ramona (Jennifer Lopez). Hustlers isn’t a love story, not even a platonic one. But Destiny is still starved for affection, connection, or any form of non-transactional contact, really. So she’s especially receptive to being taken under Ramona’s wing—or, in this case, her fur coat, under which the two women huddle during a rooftop smoke break. []

Knowing the inside story of Terry Gilliam’s history of failed or flawed projects just makes The Imaginarium Of Doctor Parnassus all the more heartbreaking. Heath Ledger’s death during filming was yet another painful setback in a career full of them, but Gilliam worked around it, bringing in a plot device that lets Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell, and Jude Law sub in for Ledger in a series of fantasy sequences. That gimmick works passably well, though in their CGI-heavy imagination-land scenes, all three actors seem hammy and flailing, with an understandable lack of connection to the character they’re playing. The real tragedy is in the film’s plot, which seems like a mighty personal story for director and co-writer Gilliam. []

Whether it’s a responsible choice to turn a real-life disaster into a stunning special effect—or to depict the natives of Thailand as “obstacles,” as opposed to people who’ve just had their own lives upended—is worth debating further. But The Impossible ultimately isn’t about the tsunami and its victims per se; it’s about this one family, and their resourcefulness in the face of disaster. Bayona’s tsunami sequence is bound to garner accolades—and rightfully so, since it’s 10 of the most harrowing minutes in recent film history—but the film is filled with smaller but no less gripping scenes of the characters scrambling toward each other, agonizingly slowly, amid a landscape of wreckage and strangers. On the whole, The Impossible is a superb example of the “man against the elements” film, driven by the panic that sets in when one family member fears never seeing the others again. With that as his starting point, Bayona deftly pushes the audience’s buttons. []

With its name cast and familiar trappings, Inside Man may come on like a conventional heist movie—even the title sounds as generic as a brown paper bag—here’s another hostage situation and police standoff—but director Spike Lee’s incapable of playing by the rules. At first, it takes some time to adjust to the film’s peculiar rhythms, which are conspicuously loose and slack by genre standards, as if Lee has agreed to take on a Hollywood thriller just to perversely extract the thrills. []Available Oct. 1

French director Patrice Confining the action mainly to the four walls of an office space, though with some subtle cinematic touches, Leconte begins with a premise that sounds like a silly comedy of misunderstanding, but evolves into a deeper, more complicated undertaking. Late for her first appointment with psychiatrist Michel Duchaussoy, Sandrine Bonnaire accidentally stumbles into the office of tax attorney Fabrice Luchini, who listens patiently and attentively as she discusses her marital problems. (Leconte doesn’t let the audience know Luchini’s real profession until later, but the lawyer’s deer-in-the-headlights expression gives it away.) Comfortable with this illusory doctor-patient relationship, Luchini takes weekly sessions with Bonnaire, continuing even after the truth is revealed. Each has a reason: She takes comfort in a good listener, while he is falling in love. []

With apologies to Don Siegel and Abel Ferrara, the best adaptation of Jack Finney’s The Body Snatchers is still the 1978 version, which unleashes the allegorical bogeymen-from-above on an unsuspecting metropolis. Whereas the 1956 original is either anti-Communist or anti-anti-Communist, depending on whom you ask, Philip Kaufman’s Invasion takes on the Me Generation—the way hippies transformed into yuppies, basically overnight. Of course, to attribute just one agenda to the film is to deny the whole spectrum of anxieties it probes; Kaufman taps into fears of biological contamination, government surveillance, urban alienation, and waking up one day to discover that the people you know and love are not who you thought they were. More so than The Conversation or All The President’s Men or any of those Watergate-era milestones, this is the great paranoid thriller of the 1970s. []

Always somewhat culturally marginal, even at the height of its original popularity, the strange countercultural take on the Synoptic Gospels known as Jesus Christ Superstar has gone in and out of acceptability since its release—at times considered cool, at others utterly beyond-the-pale lame—and grown increasingly forgotten by all but the most extreme theater nerds, which as far as I can tell are the only subcategory of the music-fandom population that has always worshipped it. But the fact is that, despite what most rock music fans may think (either because they hate Broadway musicals, religion, or both), Jesus Christ Superstar is not a corny attempt at hippying up the Bible, like its vastly inferior, non-rock Broadway musical contemporary Godspell, nor is it an example of that lamest of rock genres, born-again fundamentalist Christian rock. What it is, on the contrary, is a truly great rock record, and a fantastic movie—one that deserves to be pulled off the shelf of pop-cultural history, dusted off, and listened to again. It’s the perfect thing to play this time of year. And it’s best played loud. []

Retaining the original film’s art deco-and-Great Depression setting, Jackson’s King Kong opens on a world of big dreams and dire straits. Struggling actress Naomi Watts gives her all to vaudeville audiences who can barely be bothered to look up from their newspapers, while across town, producer Jack Black struggles to keep a jungle-adventure film afloat. In sudden need of a leading lady, Black ropes Watts into a scheme to run off with some studio resources and film on an uncharted South Pacific island. (Nothing beats a good location, after all.) After half-kidnapping playwright Adrien Brody, they set sail for the not-so-welcoming-sounding Skull Island. What happens next will be familiar to anyone who’s seen the original (or even the all-but-forgotten 1976 Dino De Laurentiis remake), but Jackson finds ways to make every moment feel new. It’s clear the director made a Kong as sure to evoke the same sense of wonder and heartbreak as the original did for him. []

If asked to make a movie about how the yuppie ascendancy of the early ’80s helped squeeze the funkiness out of New York, most filmmakers would make the yuppies the bad guys. Not so Whit Stillman. Stillman’s 1998 comedy The Last Days Of Disco follows a group of privileged young New Yorkers as they strive to cobble together a social life and an identity while embarking on careers in advertising, publishing, law, and nightclub management. Stillman makes them the heroes of his story, though he doesn’t let any of them off the hook, exactly. Like the characters in his Metropolitan and Barcelona, the young men and women in The Last Days Of Disco—played by Chloë Sevigny, Kate Beckinsale, Robert Sean Leonard, Chris Eigeman, Mackenzie Astin, and Matt Keeslar, among others—are depicted as vain, smug, and self-deluded, and they often make mistakes with dire consequences. But Stillman understands these people, and even forgives them. After all, everyone has the right to a nightlife. []Available Oct. 1

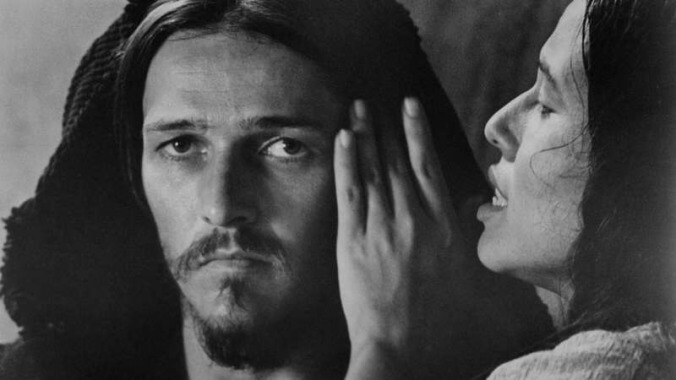

Certain films have become so inseparable from the controversies surrounding them that watching without thought to the furor becomes almost impossible. The protests greeting Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation Of Christ upon its 1988 release reached such a fevered pitch that the film itself, one of the finest achievements of Scorsese’s career, became almost an afterthought. Cooler heads never quite prevailed, but time has helped place things in perspective, allowing Temptation to be seen as the radical, profound, unabashedly reverent film it’s always been. An adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis’ sprawling novel, the film deals explicitly with the sacred paradox of the figure of Jesus: What does it mean to be both fully human and fully divine? As scripted by Paul Schrader and played by Willem Dafoe (who pulls off a nearly impossible performance), it means to struggle. Scorsese’s film presents a Jesus so fraught with conflict and doubt—emotions immediately familiar to anyone who’s ever struggled with faith—that understanding His humanity never becomes an issue. It’s this immediacy, despite the impressive recreation of the first-century Middle East, that best defines Temptation. What Scorsese has done, presenting a version of the Christ story filled with the sort of direct dialogue and troubled relationships of his contemporary films, comes from an impulse akin to that behind the creation of medieval passion plays: This is God speaking and acting in a way recognizably our own, God made one of us. [Keith Phipps]Available Oct. 1

All virtual reality and no restraint makes simple-minded Jobe Smith (Jeff Fahey) a dangerously smart boy in The Lawnmower Man, a technophobic 1992 thriller that imagines VR as a gateway to another dimension. In Brett Leonard’s film—which, despite sharing a name, bares almost no relation to Stephen King’s 1975 short story— Virtual Space Industries scientist Dr. Lawrence Angelo (a suitably frazzled Pierce Brosnan) endeavors to expand consciousness and advance evolution via experiments that combine virtual reality games and drugs. While an initial formula drives a chimp to commit murder, Lawrence finds greater success with trials on grass-cutter Jobe, a shaggy-haired, overalls-wearing simpleton who lives in a shack behind the local church and suffers abuse at the hands of both a gas station bully and a priest. All that changes, however, once Lawrence’s trials turn Jobe into a hyper-intelligent monster—part Christ-like martyr, part vengeful techno-God. []

Jonathan Demme updates Cold War paranoia for the War On Terror age with The Manchurian Candidate, a surprisingly sturdy remake of John Frankenheimer’s 1962 classic. In Demme’s 2004 redo, the bad guys aren’t the communists, or even the Iraqis whom Major Marco (Denzel Washington) finds himself fighting in Kuwait on the eve of Desert Storm. Rather, they’re the military-industrial-complex bigwigs who hunger for both profit and control of the Oval Office. To that end, the villains nab Major Marco and his team—including Raymond Shaw (Liev Schreiber), a political scion groomed for the throne by his fierce mother, Eleanor (Meryl Streep)—and brainwash them all into believing the false story of Raymond saving the whole battalion from enemy attack. Thus, the war-hero narrative is set, paving the way to a VP nomination for Raymond, who can then presumably be controlled by his corporate overlords. []

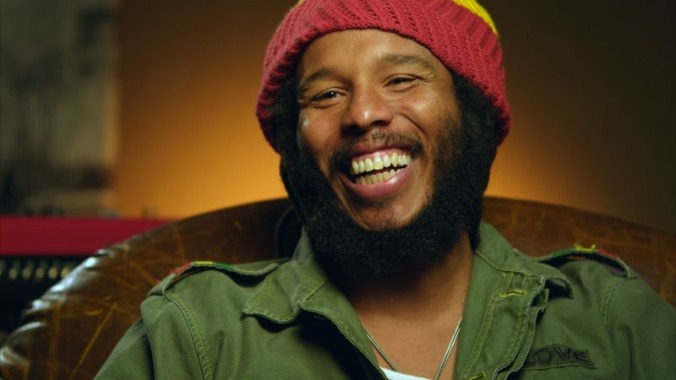

Any respectable retelling of ’s life has a lot to cover. In the 1970s, drive, charisma, and especially talent made Marley one of the biggest music stars in the world, but understanding his ascent and his music means understanding the difficult circumstances from which it emerged. It’s a lot for any film to unpack, and director Kevin MacDonald deserves a lot of credit simply for keeping the narrative coherent as Marley, his cradle-to-grave documentary, plunges into the world that created Marley and the effect his music had on that world. The film patiently establishes what it was like to grow up impoverished as an outcast in Jamaica, as MacDonald talks to everyone he can access, including Marley’s wife Rita, Bunny Wailer, cousins whose family refused to acknowledge Marley’s existence when he was young, and a fellow musician/custodian who lived with Marley when both were staying in unused rooms at a Jamaican recording studio in the ’60s. That diligence continues as the film progresses through Marley’s career, and though Marley’s son Ziggy and Island Records chief Chris Blackwell served as executive producers for the film, the subjects all give frank, open interviews that shine a light on one part of Marley’s life or another. Yet in spite of all the diligence and frankness, Marley remains an enigma. []

Jacob Aaron Estes’ extraordinary writing and directing debut Mean Creek at first appears to be a particularly skillful entry in the burgeoning subgenre of cautionary youth dramas—see 2003's Thirteen for a dire example—dedicated to the proposition that the kids today most assuredly aren’t alright. In the film’s kinetic opening scenes, Sharon Meir’s masterful cinematography lingers over budding adolescent bodies with a nervy energy that can’t help but recall the sex-saturated oeuvre of Larry Clark. Thankfully, Estes eschews the photographer-turned-director’s brittle misanthropy and penchant for sensationalism in favor of a more delicate take on the cruelty and heightened emotions of adolescence. Sure, the intricately observed inhabitants of Estes’ teenage wasteland smoke pot, drink beer, and sometimes heap abuse on each other, but most are guided by a nagging sense of morality that never becomes moralistic. Mean Creek stars Rory Culkin as a sensitive kid whose brother and friends conjure up a cruel scheme to punish portly local bully Josh Peck: They plan to lure Peck out into the middle of the river, strip him, and force him to run home naked. But they begin to get cold feet when they realize that under Peck’s obnoxious exterior lies an essentially decent human being, albeit one whose lack of social skills makes kindness and compassion difficult. []

The dynamic at a casino poker table is unique. In every other table game, all players are battling the house (and its stacked odds). Poker, by contrast, requires them to play each other, with the casino merely taking a fee—usually a small cut of each pot—for providing space on the floor and a dealer. So it’s perfectly understandable that Gerry (Ben Mendelsohn), one of the two main characters in Mississippi Grind, is a bit wary when a stranger named Curtis (Ryan Reynolds) sits down at his table and starts chatting up a storm. Curtis is friendly, sure, and he seems to be there primarily to socialize, to have a good time. In this context, however, having a really good time often involves taking money from his new buddies. Trust is an unstable commodity in the gambling world, even for two people who share exactly the same goals. As it turns out, all Gerry and Curtis have in common is recklessness, but it’s possible that that’s enough. []

Duncan Jones’ low-budget science fiction feature Moon curries a lot of favor in its first 15 minutes, which consist of star Sam Rockwell going about his daily business as the lone human employee at a power company’s lunar outpost. Rockwell cracks jokes, swears freely, and demonstrates a love-hate relationship with his over-helpful, omnipresent computer/robot GERTY, voiced by Kevin Spacey. Moon looks like a bargain-priced 2001, and has the clean, white, sterile design familiar to any thinky outer space movie made after 1968. But Rockwell’s presence gives the movie a funky humanity, and it helps that the set designers introduce some subtle smudges and clutter to reflect the presence of a man nearing the end of his three-year contract. Unlike GERTY—who expresses rudimentary emotions via a series of never-not-funny smiley/frowny/nervous faces—Moon has an honest-to-goodness personality. []

Moonstruck is a weird movie. More romantic comedies should be this weird. Hell, more movies should be this weird—this willing to throw out structural rules and play around with tone. Moonstruck is part working-class Italian American love story and part larger-than-life operatic melodrama, with just a touch of magical realism thrown in. It sits somewhere between the kitschy exuberance of Dean Martin’s “That’s Amore” and the tragic poignancy of Puccini’s La Bohème, both of which feature heavily in the score. As Roger Ebert in his glowing review of the 1987 film, “The most enchanting quality about Moonstruck is the hardest to describe, and that is the movie’s tone. Reviews of the movie tend to make it sound like a madcap ethnic comedy, and that it is. But there is something more here, a certain bittersweet yearning that comes across as ineffably romantic, and a certain magical quality that is reflected in the film’s title.” If bad luck and curses are real, maybe magical moons and love at first sight are, too. []Available Oct. 1

There’s certainly an abundance of clarity in the A Most Violent Year’s opening scene, which sees heating-oil magnate Abel Morales (Oscar Isaac), represented by his attorney (Albert Brooks, almost unrecognizable with straight hair), negotiate the purchase of an abandoned waterfront fuel yard. The terms are unforgiving: Abel has 30 days to fork over $1.5 million (closer to $4 million today), or he forfeits a sizable cash advance and the property gets sold to one of his competitors. Will things go wrong? Of course they will. Somebody keeps hijacking Abel’s trucks at gunpoint, and the district attorney (David Oyelowo) reveals that he’s conducting an investigation of the entire industry, with a special emphasis on Abel’s firm. Before long, the bank that had promised Abel the money for the deal pulls out, forcing him to beg wealthier rivals for loans, at terms highly unfavorable to him. Meanwhile, his trucks are still being robbed, and his drivers, now illegally carrying firearms at the insistence of the union boss, are engaging in shootouts on crowded highways. In order for him to meet his deadline, the personal integrity he so values will have to go on the back burner. []

Augustine Frizzell’s low-budget movie never expanded to more than 30 screens, which belies its secret, unofficial status as a model studio comedy. Its scope, scale, and 85-minute running time may be indie-style modest, but Frizzell is blessedly unconcerned with indulging in cutesy quirks or teaching anyone a lesson. Angela (Maia Mitchell) and Jessie (Camila Morrone), two teenage drop-outs living in dead-end Texas, want only to escape to Galveston for a brief beach vacation. Their plans to pay for it by working extra diner shifts are stymied by a drug deal gone wrong, gastrointestinal distress, and accidental pot-cookie ingestion—in other words, nothing too far removed from the likes of Dude, Where’s My Car? But Mitchell and Morrone make a winningly codependent pair, sort of a distaff, more self-aware version of fellow Texans Beavis and Butt-Head, and their zany antics are grounded by Frizzell’s tacit acknowledgment that their tight-knit friendship is a desperate necessity. Amazon. [Jesse Hassenger]Available Oct. 3

Very late into Obvious Child, a Sundance crowd-pleaser that actually pleases, struggling stand-up comedian Donna (Jenny Slate) issues an offhand dismissal of romantic comedies. The moment is a transparent wink, a way for writer-director Gillian Robespierre to acknowledge the genre her debut feature is loosely, eccentrically occupying. Such self-reflexivity seems unnecessary; if nothing else, Obvious Child proves that rom-com conventions require no apologies, at least when they’re invested with honesty and sharp humor. Also, a few fart jokes never hurt. []

The Paper captures a particular ’90s flashpoint. It simultaneously represents a time when Michael Keaton was a leading man, when Ron Howard was better-known for his comedies than his prestige pictures, when David Koepp was one of Hollywood’s hottest screenwriters, and when a print newspaper’s scrappiness could be determined by its relationship to a richer, more successful newspaper rather than its very existence. Howard’s film, one of his best, follows exactly 24 hours in the life of Henry Hackett (Michael Keaton), an editor at the New York Sun (loosely modeled after the Post), as responsibilities pile up. He’s got a job interview at the competing Sentinel (a broadly drawn Times spoof); his wife Marty (Marisa Tomei) is about to give birth; his boss Bernie (Robert Duvall) has cancer; the Sun’s managing editor Alicia (Glenn Close) pinches pennies; and, throughout all of this, a breaking story about a couple of teenagers arrested for a grisly murder isn’t sitting right with him. Howard’s camera bustles through the newsroom, catching snatches of fast-talking dialogue and running gags. Hackett isn’t the final decision-maker at the Sun, but Keaton commands attention because he talks the fastest—he has a way of making stammers and half-sentences sound like the product of a brain that can’t keep up with its meager human mouth. The movie creates symphonies of chatter around him: There’s one in person, with ornery reporters swarming around Henry’s office, and another conducted through a multi-line series of phone conversations, aggressive jamming of the hold button serving (along with the editing) as punctuation. The phone scene culminates with a glorious New York kiss-off—one of Keaton’s finest on-screen moments. []

The cinéma vérité horror film/mockumentary Paranormal Activity paradoxically feels more like a sequel to The Blair Witch Project than that film’s actual sequel. Like an ideal follow-up, Paranormal Activity takes the same basic premise—amateur filmmaker documents own descent into paranoia and terror at the hands of sinister unseen forces—in a bold new direction. Where Project got a lot of mileage out of the archetypal campfire-story spookiness of the wilderness where its hapless filmmakers got lost, Paranormal Activity derives much of its power from juxtaposing supernatural otherworldliness with the mundanity of the apartment where its action takes place. At best, Paranormal Activity makes the banal and commonplace deeply unsettling. The film’s resemblance to Blair Witch extends to unknown lead actors who are realistic and convincing enough to come off as shrill and unpleasant. After all, people are seldom at their best when confronted by dark powers beyond their comprehension. []Available Oct. 1

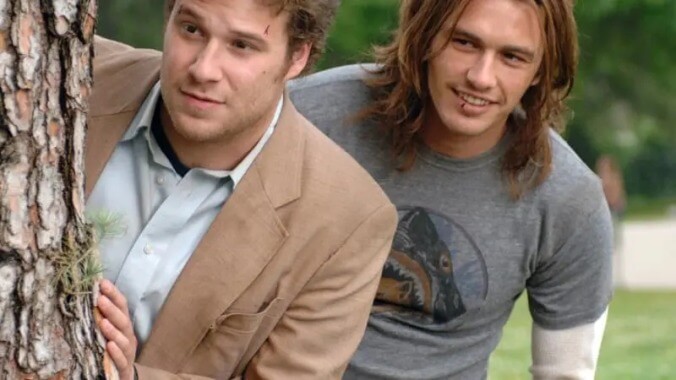

Written by Seth Rogen and his writing partner Evan Goldberg—the duo also scripted Superbad—Pineapple Express refers to an exclusive strain of weed that James Franco offers to Rogen, his favorite customer and secret best friend. Rogen’s job as a process server allows him to toke up in his car between jobs, but one night, while waiting to hand out a subpoena, he witnesses a murder, and murderer Gary Cole witnesses him right back. As it happens, Cole is also Franco’s chief supplier, and he traces the marijuana strain back to the source, sending Franco and Rogen on the run with a crooked cop (Rosie Perez) and a couple of bumbling henchmen (Kevin Corrigan and The Office’s Craig Robinson) hot on their trail. A subplot involving Rogen’s relationship with a high-school student (Amber Heard) could have been excised, though at the expense of the one of the film’s funniest scenes. But good stoner comedies like Pineapple Express have a rambling, shaggy-dog nature that can make quirky little detours and non sequiturs more essential than story itself. []

H.P. Lovecraft wasn’t generally a barrel of laughs, and his serialized short story “Herbert West: Reanimator,” originally published in 1921-22, was such a desultory paycheck effort that even the author himself reportedly disowned it. That may be precisely why it works so beautifully onscreen, transformed by the young Stuart Gordon—making an impressive feature debut—into a straight-faced gore comedy. Retaining only the title character and a handful of basic plot elements, the movie stars Jeffrey Combs as a hilariously dry, amoral medical student who’s found a way to revive dead tissue, using a neon-green fluid rather than Dr. Frankenstein’s jolt of electricity. Unlike most horror-comedies, this one simply amps up the horror and lets the comedy take care of itself. [

In spite of the technological twists, The Ring is at heart a classic ghost story, and it knows it. It allows the horror to unfold out of a campfire-ready opening scene, as two teenage girls exchange the story of the videotape while left alone in a seemingly peaceful house. The evening doesn’t go well, which prompts single mom and Seattle Post-Intelligencer reporter Naomi Watts to investigate. Her efforts lead her to a remote cabin and, inevitably, an unmarked videotape whose spooky contents could pass for unused dailies from Mulholland Dr. “Very film school,” says unimpressed former flame Martin Henderson. While he’s not far off the mark, the images have an unsettling quality that portends the troubles to come. Expanding on the strong visual sense evinced in the otherwise mediocre The Mexican, director Gore Verbinski creates an air of dread that begins with the first scene and never lets up, subtly incorporating elements from the current wave of Japanese horror films along the way. He succeeds mostly through sleight of hand. When the shocks come, they interrupt long stretches in which the camera lingers meaningfully as characters accumulate details that confirm what they already know: What they’ve seen will kill them, and soon. []

A coming-of-age film that turns Tom Cruise’s high-school senior into an accidental pimp after he nervously hires a call girl (De Mornay), Risky Business is partly about how teens grow up, discover desire, and move past the little-kid images that line their parents’ homes. But the “business” half of the title is just as important. Forced to embrace his role as a panderer after wrecking his dad’s Porsche, Cruise winds up looking at capitalism at its rawest as he joins De Mornay in the “shameless pursuit of material gratification.” But eventually, the business gets the better of him, and Cruise is troubled by the suspicion that his relationship with De Mornay might mean nothing more to her than a dollar amount, since she’s so adept at putting prices on everything else. Risky Business found its audience as part of a wave of teen comedies, but Cruise’s character has more in common with Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate than any of the Porky’s horndogs. As the film progresses, he clearly realizes his soul is at stake. If audiences in that material-world decade paid attention, they probably saw a bit of themselves up there. []

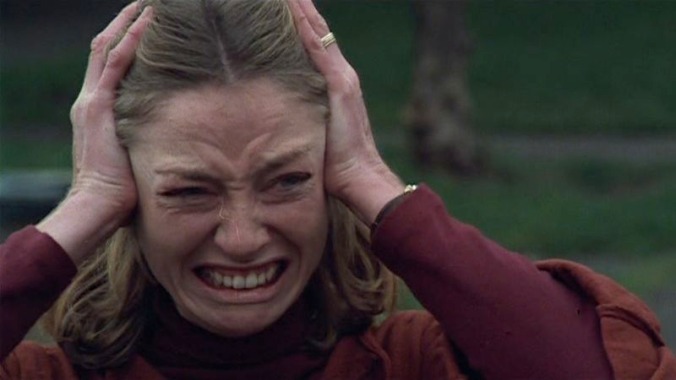

Both Larson and Tremblay are terrific in Room. For the first half of the film, Larson plays Joy as a woman who’s grown used to playing pretend: being a cheerleader for her son and exaggeratedly docile for her captor. Tremblay, meanwhile, sports the undue confidence of a pre-school kid who believes he’s learned and mastered everything he’ll ever need to know or do. It’s only after they get out that Jack becomes overwhelmed by how much more there is to life, while an exhausted Joy quickly checks out from being a mother to her son or even a daughter to her own folks, who take them in after they escape. Larson always seems to have two or three emotions playing across her face simultaneously, while Tremblay straddles the line throughout between “bright little boy” and “stubborn brat.” Room should hit home with everyone who worries about how to tell the generation behind them what lies ahead—especially when we can’t always see what’s in front of ourselves. []

In the afterword to the 2003 edition of Ira Levin’s novel Rosemary’s Baby (reprinted in the booklet included with The Criterion Collection’s new Rosemary’s Baby Blu-ray edition), Levin writes about how the success of the movie touched off a wave of occult horror movies in the ’70s, and adds, “Here’s what I worry about now: If I hadn’t pursued an idea for a suspense novel almost 40 years ago, would there be quite as many religious fundamentalists around today?” Levin’s asking this somewhat puckishly, but it’s a valid question. There had been schlocky B-movies about devil worshippers before, but ’s adaptation of Rosemary’s Baby was a big Hollywood studio prestige project, with high production values and a striking blend of nightmarish fantasy and naturalism. And as Polanski leads the audience step-by-step through Levin’s queasy plot, he pushes them toward a conclusion straight out of a Louvin Brothers gospel song. Oh yes, brethren: Satan is real. []

A plump, severed toe floats to the surface of a meat stew, ready to be unwittingly gobbled. A decapitated head rolls down a chimney, then springs to maniacal, vaudevillian life, shouting and singing. A spider bite on a cheek keeps growing and growing and growing, until… well, arachnophobes beware. Like scouts huddled around a campfire, each trying to send a bigger chill down the others’ spines, Scary Stories To Tell In The Dark keeps coming up with new gruesome attractions, piling one on top of the next. Yet as gross and spooky and, yes, occasionally frightening as these terror tactics get, they never quite cross over into the deep end of truly grown-up horror. That’s intentional, and a key to the film’s fun: It gets away with everything it can on a PG-13 leash, smuggling some real scares to the under-18 crowd. []

Brilliantly photographed in black and white by Janusz Kaminski, Schindler’s List looks alternately luminous and stark, with a bracing contrast between the elite German bacchanals, lit with an elegance worthy of Marlene Dietrich, and footage of Polish labor camps, which have a newsreel immediacy. The film goes well beyond the merely solemn and tasteful, honoring history without cardboard villains and heroes, and without putting the shackles on artistic expression. Cynics might blame Spielberg for salvaging uplift from the ultimate tragedy, but the film’s hopefulness cannot be so easily extracted from its searing, vivid horrors. On the contrary, it’s a film that above all holds precious the continuity of the Jewish people, which is exactly what the Nazis tried to extinguish. []Available Oct. 1

After scaring the wits out of millions, Jonathan Demme’s The Silence Of The Lambs joined It Happened One Night and One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest as one of the few movies to score Oscars in all five major categories (Picture, Actor, Actress, Director, Screenplay). Hiring Demme, surely among the warmest and most humane American directors, to handle such a violent story turned out to be a masterstroke of casting against type: He knew from his early years working for Roger Corman how to deliver the genre goods, but his empathy, particularly with regard to women, is what makes the film so enduring. Jodie Foster’s journey makes the film a terrifying fable, and far more than the sum of its overflowing case file. []

Willis stars as a Philadelphia psychologist who, shortly after receiving an award for his work with children, is confronted in his home by a disturbed former patient (Donnie Wahlberg), who feels Willis failed him. A year later, he encounters a child (Haley Joel Osment) who reminds him of Wahlberg, a boy who eventually reveals he has some traffic with the supernatural. Though not without some genuinely frightening moments, The Sixth Sense is less a horror film than a moody piece of magic realism. Shyamalan’s approach, composed largely of Kubrickian extended takes, has a sense of purpose and an artful construction that respects both its story and its audience, allowing both to take their time sorting things out. It’s a style that also brings out the best in its cast; Willis has rarely been better, and both Olivia Williams (as Willis’ wife) and Toni Collette (as Osment’s overworked, deeply concerned mother) turn in convincing performances. Also great—and had he not been, the film would have been ruined—is Osment, whose unrelenting gravity and ability to convey sadness beyond his years threatens to give a good name to child actors. The Sixth Sense teeters on the brink of New Age ludicrousness, but it never goes over: Like Kieslowski and others, Shyamalan knows that what makes for lousy metaphysics can make for powerful metaphor, and in the end he creates a deeply, surprisingly affecting film out of a little bit of smoke and brimstone. []

Spaceballs wasn’t one of Brooks’ great successes, but it’s endured in the shadow of Star Wars as a lone “official” parody version. In retrospect, its comic deconstruction of the most successful movies of all time looks more respectful than Lucas’ own prequels, which ultimately seemed to understand less about the appeal (and pitfalls) of their source material. Certainly, George Lucas had good intentions when he tried to redo his own greatest hits, but as Spaceballs teaches us, good is often very, very dumb. []

The Spanish Prisoner is named after a legendary long con, and here Campbell Scott, in full-on Jimmy Stewart “aw-shucks” mode—he is repeatedly referred to as a “boy scout”—plays the innocent man snared in a web of dark conspiracy. Scott’s Joe has created some mathematical equation referred to as the “process,” which is about to make the company he works for loads of money. Meanwhile, he’s still bugging his boss (the inimitable Ben Gazzara) about his bonus. On a trip to the Caribbean to parade the process in front of some bigwigs, Joe meets the enigmatic Jimmy Dell (Steve Martin, masterfully playing against type). It was a genius stroke from David Mamet, who wrote and directed, to cast Martin: By 1997, everyone knew how much simmering energy the comedian contained underneath, so his calm, collected Jimmy is clearly a master of control, which only adds to his menace. []

A Sundance coming-of-age movie is on the short list of Things We Never Need To See Again, but James Ponsoldt’s romance between a teenage alcoholic and his sweetly shy classmate was executed with uncommon sensitivity and featured two of the year’s best performances from Miles Teller and Shailene Woodley (as well as Short Term 12’s Brie Larson and Nebraska’s Bob Odenkirk). In a sense, The Spectacular Now is a teen riff on Ponsoldt’s previous film, Smashed, but it’s both more hopeful and more melancholy, charged with the possibilities peculiar to adolescence as well as the knowledge that few ever live up to their potential. []

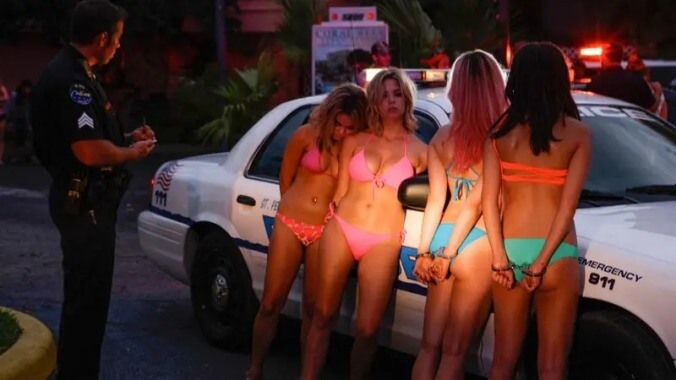

Having shot Trash Humpers on VHS, Harmony Korine goes the opposite direction with this gorgeous, widescreen, neon-splattered approximation of a mainstream effort, achieving a near-perfect fusion of exploitation and poetry. It’s certainly his funniest and most aesthetically accomplished film, from a long-take chicken-shack robbery seen from the getaway car’s point of view to fragmented editing as graceful as any in To The Wonder. Following the odyssey of four Christian-college students (mostly played by Disney TV graduates) who travel to Florida to test their boundaries of getting fucked up, the movie turns increasingly satirical as it becomes clear their definition of being bad doesn’t stop short of violence. As Alien, the drug kingpin who ushers the women into a new world (and leads them in them in a jaw-dropping rendition of Britney Spears’ “Everytime”), James “I’ve got shorts, every fuckin’ color” Franco delivers his most entertaining performance. []

Although it’s a reductive statement, calling Swallow a high-class version of My Strange Addiction isn’t entirely inaccurate. Its heroine, wealthy housewife Hunter (Haley Bennett), suffers from a rare eating disorder called pica, which compels her to swallow small, non-food objects, the sharper and more damaging to her internal organs the better. Soon after finding out she’s pregnant, Hunter begins with a lovely little glass marble, then levels up to thumbtacks, jacks, a double-A battery, and handfuls of dirt, among other tchotchkes. The film contains multiple scenes of Bennett doubled over in pain in immaculately appointed bathrooms, as her terminally meek, deeply repressed character subconsciously punishes herself for perceived sins that won’t become evident until later. Those sins, along with Bennett’s performance, are what make Swallow more than just a beautifully shot freak show—though the visuals don’t hurt either. []Available Oct. 8

Nobody gets sliced or diced in Sword Of Trust, but neither is the film’s title wholly metaphorical. There’s an actual sword to be reckoned with, one that was allegedly instrumental in the South winning the Civil War. If that sounds like obvious nonsense to you, join the club: Birmingham pawn shop owner Mel (Marc Maron) isn’t buying it, either. He might buy the sword, though, after his dopey, conspiracy-minded assistant Nathaniel (Jon Bass) does some quick Googling and discovers an entire wacko fringe that fervently believes the Confederacy was victorious, and are willing to pay top dollar for supporting evidence. Unfortunately for Mel, the sword’s current owner, Cynthia (Jillian Bell), and Cynthia’s wife, Mary (Michaela Watkins), insist on being part of the negotiation, since they need the proceeds to buy the house Cynthia had mistakenly assumed she was inheriting. Before long, the four of them are huddled together in the rear of what looks like a serial killer’s van, being driven to meet with a potential buyer whose identity is unknown. []

Much of the success of Terminator 2 is in the elegance of the storytelling. Director James Cameron sets it all up beautifully, introducing all his key characters one by one, slowly pushing them all to the point where they’ll intersect. Schwarzenegger’s foe, the shape-shifting T-1000, is understated but deadly compelling. Robert Patrick’s face is all planar surfaces, he runs with a freaky sense of focus, and he projects a dispassionate authority that allows him to slip through society more easily than Arnold Schwarzenegger. Sarah Connor, the previous movie’s hero, has had a rough time since we’ve seen her pregnant, driving off into an electrical storm. She’s all hair sweat and sinew and feral intensity. She’s been committed to a mental institution because she won’t stop telling everyone that the end of the world is coming, but also because she’s legitimately disturbed and unstable. Whenever Linda Hamilton goes full-tilt in T2, it’s magic: holding the Drano-filled needle to the psychiatrist’s neck, scolding her son for being dumb enough to come save her, screaming cuss words at the family of the man she’s just shot. Hamilton should’ve won the Oscar that year. She wasn’t even nominated. []

The studio system collapsed in the ‘60s, but every now and then, attentive mainstream filmmakers are able to recreate the creative conditions that produced so many seamless prestige pictures during Hollywood’s Golden Age. In many ways, the 1982 comedy Tootsie is a product of its time, from its bustling Dave Grusin score to its “boy, those modern women sure have it tough” theme. But it’s also a study in craft, put together by a crew of actors, writers, and technicians at the top of their games. It’s that rarest of high-toned Hollywood products: a pointed farce that ticks like a clock and rings like a bell. []

Top Gun follows Cruise to a school dedicated to reviving what an opening scrawl calls the “lost art of aerial combat,” There, Cruise (codename: “Maverick”) takes risks to obtain the “Top Gun” trophy he wants, much to the chagrin of Val Kilmer (codename: “Iceman”), who follows the rules to the letter. The greatest obstacle to Cruise’s goal comes with the death of his friend and flying partner Anthony Edwards, but in the end, he accepts that Edwards was just the guy who rode in the back of the plane, and sometimes the second bananas die. Besides, Edwards called himself “Goose,” so what did he expect? The message: Exceptional people get a free pass, so long as they act in the interests of their own success. The romantic subplot with Kelly McGillis, scored to the immortal Berlin song “Take My Breath Away,” ultimately reveals itself as a long, sexy distraction. Top Gun could just as easily be a film about selling vacuum cleaners. That might not have moved as many tickets, but Scott could conceivably have made it work. Collaborating with producer Jerry Bruckheimer and his partner Don Simpson, Scott made the smoothest jet-fighting melodrama imaginable, shot it in a gauzy sunlit style that would forever signify the summer of 1986, and reached an audience of millions. They set a goal and achieved it. []Available Oct. 1