The best Netflix documentaries...that aren't Tiger King or Making A Murderer

Dozens of other terrific non-fiction titles can be found on the streaming service

People who love documentaries love Netflix because the streaming service offers so much compelling long-form non-fiction content. We know you’ve read enough about Making A Murderer and Tiger King (and no, you won’t find Tiger King 2 on this list), so we’ve looked beyond those titles. This broad list encompasses other great documentaries that have been touted on The A.V. Club and are currently available on Netflix.

Looking for other movies to stream? Also check out our list of the best movies on Amazon Prime, Disney+, Netflix, and Hulu.

Any social-issues documentary worth a damn has at least one moment—one statistic, one anecdote, one archival snippet—destined to boil the blood of its audience. But in 13th, from director Ava DuVernay, those agitating moments keep coming and coming, one after another, creating a blitzkrieg of outrage. The title refers to the 13th Amendment, which officially abolished slavery in 1865, “except as a punishment for crime.” The documentary argues that this particular choice of words became a free-labor loophole in the South, creating incentive to lock up black men on minor charges and to paint them as inherently criminal. That may seem like a cut-and-dry thesis, but over the course of just an hour and 40 minutes, 13th tackles the war on drugs, the Central Park Five, Jim Crow, Willie Horton, police shootings, mandatory minimum sentences, The Birth Of A Nation (no, not ), and a dozen other related topics. The result is nothing less than an abbreviated history of racial inequality in America, with the prison system as the vortex at its center. []

This stunning, gut-churning documentary that blew up the festival circuit before landing on Netflix, is a must-see chronicle of why we should never trust anyone, ever. The true story of an Idaho preteen who was groomed and sexually abused by a family friend as her parents stood idly by, too trusting to fully acknowledge the reality of the situation, is brimming with moments that will first make you scream, but then make you ponder how you would react in a similar situation, especially under these particular circumstances. []

Unlike or any given episode of 48 Hours, Netflix’s Amanda Knox doesn’t seek to build mystery or suspense: One of the first shots is of Knox herself, talking straight to camera, clearly not behind bars or in prison clothes. She introduces her nearly unbelievable story with a frightening binary: “Either I’m a psychopath in sheep’s clothing, or I am you.” By “you” she means any innocent person who might find themselves in prison for something they didn’t do. Amanda Knox is her story, it bears her name, and the documentary wants viewers to believe her. That’s easy to do because the evidence is clear, but it doesn’t make the story itself any less harrowing or fascinating. []

The first film from Barack and Michelle Obama’s Higher Ground Productions is inherently political, but it’s more complex than agitprop. Following the reopening of a shuttered factory in Dayton under the new ownership of a Chinese auto-glass company, directors Steven Bognar and Julia Reichert offer a startling intimate look at the struggle to blend two working cultures. Never descending into xenophobia or condescension, their documentary makes the point that the issues matter because of the effect they have on the people. []

From its opening scene, Amy is almost more noteworthy for what it doesn’t do as a documentary than for the sad story of its famous subject. Director Asif Kapadia () opens his film not with a montage of talking heads spouting money quotes about Amy Winehouse, but with a home movie of teenage Winehouse hanging out with friends for someone’s birthday. A few of them begin tunelessly singing “Happy Birthday To You,” their voices fading when an off-camera Winehouse finishes the song with the kind of overstated flair possessed by someone who likes showing off her knockout pipes. []

There’s a lot that’s alarming and unsettling about the documentary Audrie & Daisy, but nothing chills the spine quite like the interviews with two of the high-school kids convicted of sexually assaulting their classmate Audrie Pott. Pretty and popular, Pott had been an object of attention for a clique of football players almost from puberty. As the boys explain in their interviews, they had a private online account for sharing nude photos of their female peers, many of whom posed for them willingly. But Pott didn’t want to play along. When she got drunk at a party one night, they stripped her, raped her, drew all over her naked body with markers, and then triumphantly shared the pictures. Years later, talking about the incident on camera, they own up to every bit of this, yet still seem uncertain about exactly what they did wrong. []

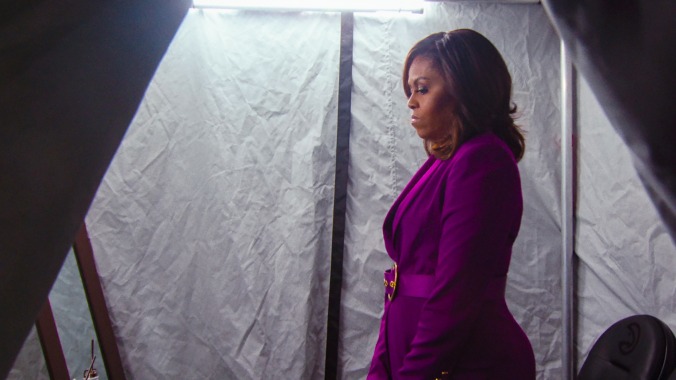

After more than 15 years in the spotlight, it may seem like we know all their is to know about former First Lady Michelle Obama, but, “this is totally me, unplugged, for the first time,” she declares—and she’s not wrong. Directed by Nadia Hallgren, the inspirational Becoming follows Obama as she engages with local communities of young women on a 34-city tour. Along the way, we’re treated to her thoughts on the criticism she’s faced over the years, her relationship with her husband, and how she maintains positivity even under the darkest of circumstances. Teach us all, please. [Patrick Gomez]

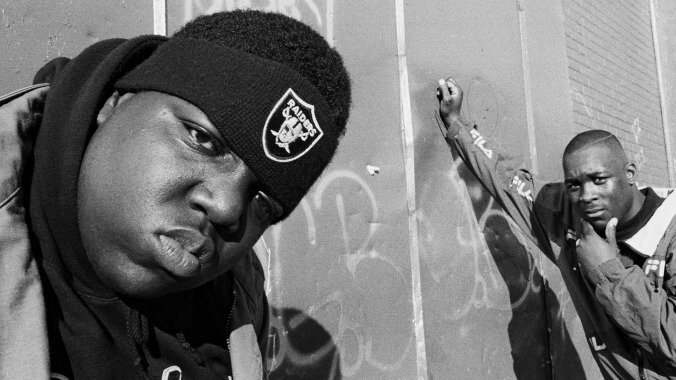

Biggie immediately establishes that we’ll get to see a more honest, personal side of the late MC. The documentary begins with a stream of camcorder footage, catching Wallace as he tours all over the place in ’95, riding high off the success of his debut album, Ready To Die (a.k.a. the record that saved East Coast hip-hop), and smash hits like “Juicy” and “Big Poppa.” There are glimpses of a lighter, more playful attitude—joking around and partying with his buddies—that Wallace adopted when not in Biggie mode. It comes out during a filmed interview where the rapper (probably under the influence of some decent weed) answers questions in a lackadaisical, indifferent manner. “Christopher Wallace is a conscious person,” says Damion “D-Roc” Butler, childhood friend and tour videographer, at one point. “He knows what the hell is going on. Notorious B.I.G., he didn’t really give a fuck.” []

Kitty Green, the director of Casting JonBenet, spent 15 months in Boulder, Colorado, where Ramsey’s 6-year-old body was found, on December 26 of 1996, in the basement of her family home, tucked underneath a blanket. Most of the film is presented as audition footage, with people from the area—many with little to no screen experience—trying out for the role of Ramsey herself, as well as the roles of her parents, John and Patsy, and her older brother, Burke. Green cuts judiciously throughout to scene-setting reenactments starring these amateur actors, shot with a cool-blue gleam somewhere between Fincher and Lynch on the murder-mysteries-by-David spectrum. It’s clear, however, that the real purpose of the project isn’t this incomplete film-within-the-film but the interviews with its prospective stars, assembled into a court of public opinion to discuss their own recollections, hypotheses, and personal feelings about the Ramsey case. []

“The world wants us dead.” That statement is delivered, if not quite casually, then with startling clarity by one of the disability rights advocates interviewed in Crip Camp. Some might be shocked by the candor. But as this Netflix-released documentary makes clear, people with disabilities don’t have the luxury of being surprised by society’s indifference toward them. Able-bodied people may feel uncomfortable if a blind person doesn’t wear sunglasses or if they can’t understand the speech of someone with cerebral palsy. Now imagine being on the receiving end of that discomfort every day of your life, as disgust and pity are piled on top of constant reminders of how little the rest of the world thinks about you and your needs. A humanizing emphasis on providing those who live with these experiences the opportunity to recount them is where this otherwise conventional documentary shines. []

If is your favorite Kirsten Dunst movie, have we got the documentary series for you. Cheer focuses not on the Rancho Toros, but the real Navarro College Cheer Team in Corsicana, Texas, which has won 14 national championships since 2000. The team is coached by Monica Aldama—described as a “beast”—whose motto is, “You keep going until you get it right, then you keep going until you can’t get it wrong.” That explains all those championships: One shot in the trailer shows a cheerleader soaking in a bathtub full of ice. [Gwen Ihnat]

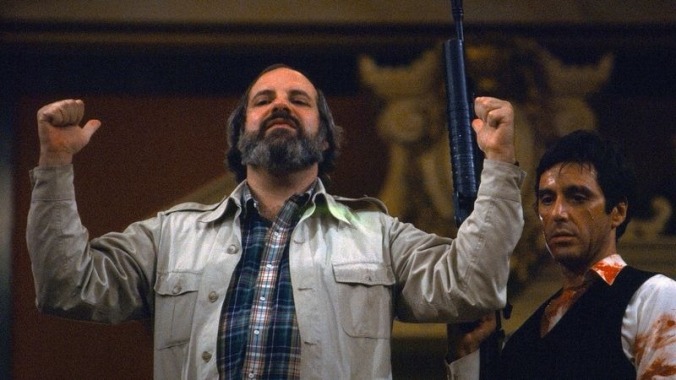

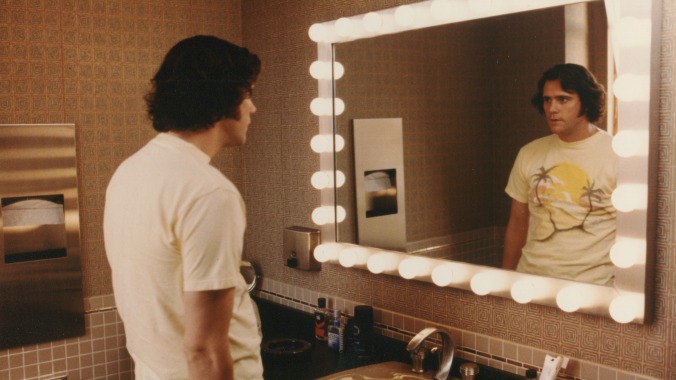

To open a film about the life and career of Brian De Palma with a clip from Vertigo is almost too on the nose, like ending the greatest thriller of all time with a doctor clinically diagnosing its killer. Not that the maker of The Untouchables, , and two dozen other exercises in obscenely virtuosic style resents the comparison. De Palma, the most divisive of the major directors to emerge from the New Hollywood camp, has spent four decades proudly operating within the iconic silhouette of Alfred Hitchcock. Toward the end of De Palma, an entertaining new documentary companion to his work, the 75-year-old filmmaker even positions himself as a proper heir—the one true disciple to actually build upon Hitch’s lessons, to makeover the master’s approach for a new era. Egotistical? Maybe, though anyone who sits through this feature-length highlight reel—packed with excerpts of stunning set-pieces, all supportive of his claim that a director’s duty is to make the material as visually interesting as possible—may walk out more convinced of his torch bearing than not. []

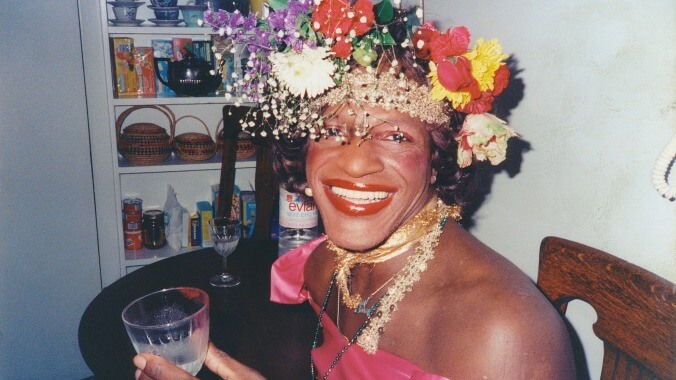

Directed by David France, The Death And Life Of Marsha P. Johnson is ostensibly about the title character: a gay pride pioneer who participated in the Stonewall uprising, and who remained a vocal advocate for the rights of New York’s street-dwelling outsiders in the 1970s and ’80s. Born Malcolm Michaels—and known by friends as “Mikey,” “Michelle,” or “Marsha”—Johnson self-identified as a drag queen and transvestite in the era before transgender people began fighting en masse for more precise terminology. She was found dead in the Hudson River in 1993, in what the police initially ruled a suicide. But those who knew her joie de vivre and history of mentoring runaways and street prostitutes suspected that she’d been murdered. France does a remarkable job of finding the continuity between New York in the ’70s, ’90s, and now. Like How To Survive A Plague, this documentary acknowledges progress, while noting that the issues that gay rights pioneers were struggling with have never fully gone away. If nothing else, that’s a necessary corrective to the impression that everything’s okay now for every (or any) color on the LGBTQ rainbow. []

Documentarian Alex Gibney (, , ) is doing the lord’s work with Dirty Money, a Netflix docuseries that digs into just how comically evil the 1% truly is. The first season of the Gibney-produced series dug deep into payday loans and pharmaceutical corruption—not to mention our president’s history of shady dealings—and its follow-up zeroes in on the Wells Fargo banking scandal and Malaysia’s 1MDB corruption case, among other depressing things. Dirty Money’s biggest star in its second season, however, is another figure close to the president: Trump senior advisor Jared Kushner. In an episode directed by Dan DiMauro and Morgan Pehme—who helmed Netflix’s excellent —Dirty Money pulls back the curtain on the Kushner clan’s real estate practices, which are . [Randall Colburn]

This three-episode miniseries packs a suspenseful punch showing you just how vast the World Wide Web is and how even the smallest detail of information can be a vital piece in a gigantic puzzle. True-crime documentaries don’t usually give me the creeps, but this one certainly had me rethinking every choice I ever made regarding my social media footprint. Though the holiday season is supposed to renew my faith in humanity, Don’t F**k With Cats did just the opposite. [Angelica Cataldo]

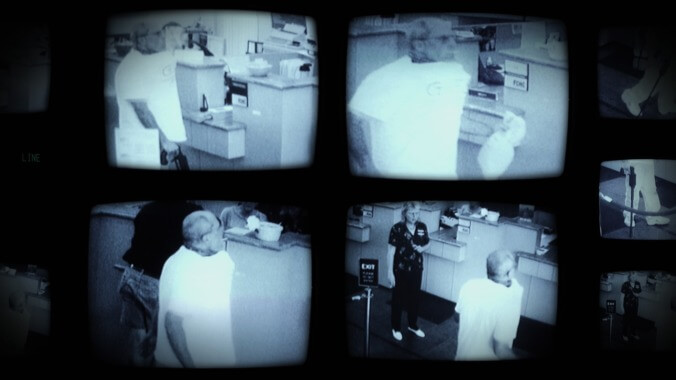

Some of Netflix’s true-crime series start with a fascinating case, then expand their focus to engage with larger social issues: and corruption, for example, or and institutional memory. However, in Evil Genius: The True Story Of America’s Most Diabolical Bank Heist the streaming service decided to eschew deeper meaning, and just take viewers on a ride. The story begins on August 28, 2003, when 46-year-old pizza delivery driver Brian Wells was recorded on security cameras walking into the PNC Bank on Peach Street in Erie, Pennsylvania with a strange, bulky object under the collar of his white Guess T-shirt. He presented a pre-written note to a teller explaining that the object was a collar bomb, and demanded $250,000. When the bank was unable to produce the full amount in the stated 15-minute time frame, Wells exited the building with a bag containing about $8,000. He then sat down in the parking lot between two squad cars, told assembled officers that two men had strapped the bomb to his neck after he was called to deliver a pizza to a remote radio tower, and, when the bomb detonated, died in full view of local news cameras while the bomb squad was stuck in traffic. This all occurs within the first half-hour of the first episode. []

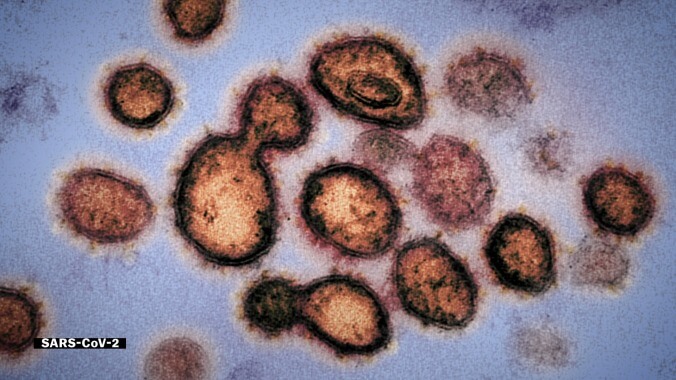

A half hour (or sometimes just 16 minutes) may not be enough time to make you an expert on any one subject, but this docuseries—based on Vox’s popular weekly YouTube series—distills subjects ranging from the rise of cryptocurrency to why diets fail to the expansion of K-pop down to digestible nuggets of knowledge. It’s even spawned special seasons focused on sex (narrated by Janelle Monáe) and the mind (narrated by Emma Stone). In April 2020 they released Coronavirus, Explained, narrated by J.K. Simmons. Oddly (or maybe not?) the Farmers Insurance guy makes for the perfect, soothing guide through the pandemic. [Patrick Gomez]

Among the eccentric secondary characters of film history, few are as puzzling as Leon Vitali, the English actor who left behind his career to become a personal assistant of director Stanley Kubrick. Filmworker (as opposed to “filmmaker”), the title of Tony Zierra’s documentary about Vitali, was his preferred term for this peculiar calling. For more than 20 years, Vitali was Kubrick’s go-between, research assistant, talent scout. He coached Kubrick’s actors and took his notes. When Kubrick was preparing his Stephen King adaptation, , he sent Vitali on a trip around America to take pictures of hotel kitchens; when one of the director’s many cats got sick, it was up to Vitali to set up a closed-circuit TV system so Kubrick could keep watch from anywhere in his secluded mansion. And when the notoriously private filmmaker needed to fire off a strongly worded missive to studio executives or a film lab, he would sometimes sign it “Best, Leon Vitali,” leaving his assistant to field the apologetic follow-up call. But what does a person who has given over the best years of his life to being micro-managed by a perfectionist do when the master is gone? []

In times of peril, some people feel compelled (or are, in fact, legally compelled) to pick up a weapon. There’s no shortage of guns and bombs in Five Came Back, writer Mark Harris and director Laurent Bouzereau‘s three-part wartime documentary, but the weapon in focus is of a very different sort. This is a series about the power of a camera, particularly when there’s an artist peering through the lens. []

Chris Smith directs Fyre—about the notorious Fyre Festival, the wannabe luxury music fest put on in the Bahamas that briefly took social media by storm when in the spring of 2017—with a razor-sharp point of view and eye for crafting a narrative that captures surprising, small moments of human foibles amid all the madness. (His résumé includes and 2017’s Netflix doc .) Smith knows just how outrageous this story is, and lets his narrative be guided by the inside scoop from his parade of subjects, nearly all of whom witnessed firsthand this slow-motion train wreck of a music festival as it unfolded. []

Is it possible to talk about the fascinating and complex universe of black hair without dealing with race and identity? That’s the question posed by Good Hair, director Jeff Stilson and co-writer/producer/narrator/star Chris Rock’s charming new comic exploration of African-American hair. The film is filled with sadly telling moments, like a black beauty student telling Rock that she’d have a hard time taking a job applicant seriously if he had an afro, yet its tone is one of amusement rather than indignation. Rock is an entertainer, not a polemicist, and Good Hair will never be mistaken for a college course in African American Hair And Racial Identity, though it does stress the pain women will endure and the exorbitant prices they’ll pay to keep up with follicular trends. To the film’s subjects, paying thousands for a complicated, high-maintenance weave is less a luxury than a necessity, even for those low on the socio-economic scale. Borrowing moves from Michael Moore and Morgan Spurlock, Good Hair alternates funny, candid talking-head interviews with famous folks like Nia Long, Ice-T, Al Sharpton, and Raven Symone with prankish stunts like Rock trying to sell African-American hair on the street and an extended trip to the Bronner Brothers Hair Show. During the climactic Hair Show competition, stylists battle in flamboyant production numbers that take showmanship to comic extremes, from a fuzzily conceived bar scene involving an aquarium and underwater hair-styling to a dizzy spectacle involving more or less an entire marching band. []

“When I decided to do Coachella, instead of me pulling out my flower crown, it was more important that I brought ourculture to Coachella.” Though she chuckles warmly at her joke, there is a quiet power couched in Beyoncé’s mission for her historic 2018 festival set, stated roughly 32 minutes into the Netflix documentary . The idea of carving out a space at the largest music event of the year—one that is not-so-secretly consumed by a predominately white audience—to unabashedly celebrate black culture might ring as too ambitious of an undertaking for most to seriously entertain. But as we witness throughout this vibrant documentary, the journey isn’t exactly for the faint of heart and can be an upward climb for even the most time-tested of legends among us. []

Twenty-two years is an enormous chunk of life to sacrifice to a false prophet and his empty promises of spiritual salvation. But when budding filmmaker Will Allen emerged from the cult that had used and abused his devotion for more than two decades, he at least had something to show for the time lost: reels upon reels of footage, the cinematic record he had amassed as the group’s official documentarian and unofficial propaganda minister. Holy Hell is the fruit of that labor. Through a combination of his vast library of home movies and a series of talking-head interviews conducted with his fellow duped, Allen invites audiences to relive all 22 years spent under the spell of a charlatan; he’s reverse-engineered an undercover exposé of life within a cult. []

Hard-bop trumpeter Lee Morgan, one of the virtuosos of the stylistic explosion that followed postwar bebop, was shot in the chest during a late-night gig at the already notorious Lower East Side club Slugs’ Saloon by his common-law wife and manager, Helen More, and bled to death while awaiting an ambulance that was trapped for almost an hour in a snowstorm. Part character study in codependence, part true-crime doc, I Called Him Morgan examines the lives of Morgan and More through talking-head interviews with bandmates and associates, archival photos, and a cassette-tape interview with More conducted in 1996 by Larry Reni Thomas, a jazz historian who befriended her while teaching an adult education class. For Swedish documentarian Kasper Collin (My Name Is Albert Ayler), the true point of interest in the story is More, whose personality emerges in fragments. A widow and mother of two before the age of 20, she escaped North Carolina to New York City, where she made her home a popular hangout for jazz musicians and bohemians. The argument that led her to return to Slugs’ with a revolver was over Morgan’s relationship with another woman (also interviewed here), though I Called Him Morgan makes it clear that years of drug abuse had left the jazzman impotent. It was, in other words, strictly emotional. []

Bryan Fogel’s documentary tells such an eye-opening story that it almost doesn’t matter when the storytelling itself gets a little sloppy. An actor and playwright best known for the comedy Jewtopia, Fogel is trying his hand at feature-length non-fiction filmmaking for the first time with Icarus, and he just happened to stumble onto the kind of relevant, ripped-from-the-headlines scandal that investigative journalists spend years trying to dig up. What starts out as a -esque stunt—with Fogel injecting himself with performance-enhancing drugs to compete in an amateur cycling race—becomes a wider-ranging exposé of doping in organized sports. And then it takes a darker but in retrospect inevitable turn, as the filmmaker’s foray into the shady world of PEDs brings him into contact with a network of Russian scientists who’d rather not get caught on camera. []

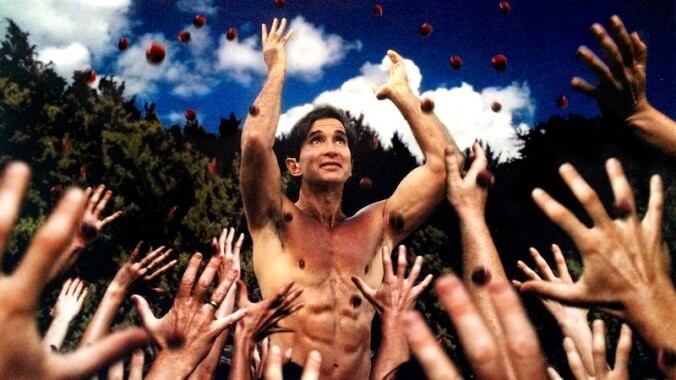

Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond—Featuring A Very Special, Contractually Obligated Mention Of Tony Clifton (yes, that’s the actual title) is a documentary constructed from behind-the-scenes footage shot for , the 1999 Andy Kaufman biopic starring Jim Carrey. This material, intended for the usual DVD extras and so forth, proved to be so abrasive and potentially alienating that it was never used, and has been sitting on the shelf for two decades. Carrey, a Kaufman fanatic, had obsessively campaigned for the role; once he won it, he wasn’t about to relinquish it. He remained Kaufman—or Kaufman’s cartoonishly obnoxious lounge act of an alter ego, Tony Clifton—at all times, resurrecting the prankster’s button-pushing idiosyncrasies and uncomfortably realistic fake feuds. When wrestler Jerry Lawler showed up to play himself, Carrey went way too far in taunting him, just as Kaufman surely would have. And pity Man On The Moon’s director, two-time Oscar winner Miloš Forman (, ), who’s repeatedly seen struggling to engage his star in serious and necessary conversations about the work, only to be met with Kaufman’s calculated indifference to convention or Clifton’s standard barrage of insults and anarchy. []

Every year, thousands of people pay more than $350 to eat sushi at a 10-seater restaurant in a Tokyo subway station, making reservations at least a month in advance to dine at one of the few fast-food stands in the world to earn three stars from the Michelin guide. The proprietor, Jiro Ono, is in his mid-80s, and has spent his life innovating and refining, always asking himself, “What defines deliciousness?” David Gelb’s Jiro Dreams Of Sushi shows what a meal at Sukiyabashi Jiro is like: each morsel prepared simply and perfectly, then replaced by another as soon as the previous piece is consumed, with no repetition of courses. Once an item is gone, it doesn’t come back. That’s why each one has to be memorable. []

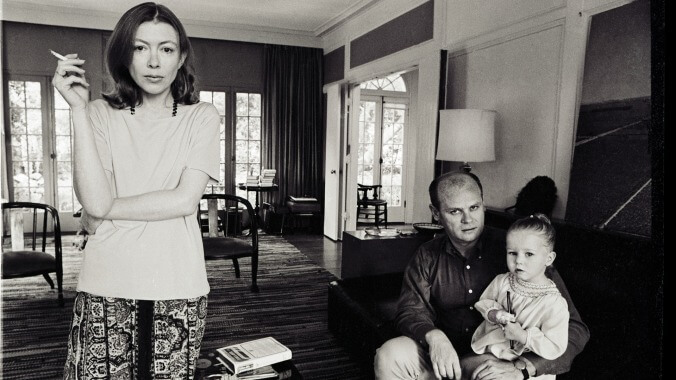

There’s something amazing about watching Joan Didion, the 82-year-old essayist, public intellectual, and icon of American culture, respond to being asked what it was like as a journalist in 1967, walking into a room and seeing a 5-year-old child on acid. After a long pause, she speaks: “Let me tell you, it was gold.” That searing sense of honesty imbues The Center Will Not Hold with a magnetism as powerful as the voice at its center. Given that relative Griffin Dunne directed, one might expect hagiography, but despite the fact that nary a single negative word about Didion is uttered, this documentary feels raw and real. It ranges freely from her early childhood to the pain of losing her daughter and Blue Nights (the book where she discusses that loss), and all of it only serves to reinforce the idea that the film could be 10 hours long and still never exhaust its subject, whose writing Dunne often returns to as proof of her volcanic intellect and penetrating insight. How vital is Didion? Harrison Ford shows up to discuss being her carpenter in ’70s Malibu, and all you want is to get back to Joan. [Alex McLevy]

This documentary ostensibly revolves around the 1969 murder of Sister Cathy Cesnik, a beloved teacher at a Baltimore Catholic high school whose case remains unsolved nearly 50 years later. But she’s only a small part of a bigger puzzle—which is how Sister Cathy, who’s painted with a saintly brush throughout the series, would have wanted it. Like Making A Murderer, The Keepers is concerned with mechanisms of power and how they are maintained. But rather than delving into the twists and turns of a criminal case, it asks why certain crimes aren’t investigated. The series is also a testament to the tenacity and determination of women, particularly older women, who keep pounding on the doors of the criminal justice system even when those doors are repeatedly slammed in their faces. []

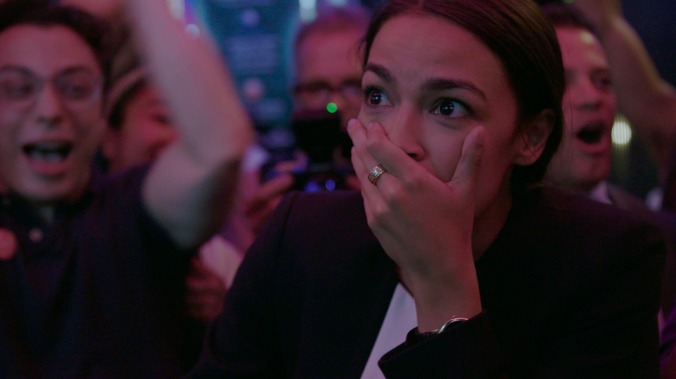

There’s an interesting debate to be had about whether political art requires an audience to agree with its partisan point of view ahead of time in order to be successful. No such concerns need intrude on the enjoyment of Knock Down The House, largely because—despite focusing on progressive campaigns against establishment politicians from overtly leftist challengers—actual policy takes a backseat to the scrappy underdog stories the film highlights. There’s a timeless appeal to watching David take down Goliath with little more than a slingshot, and in lucking into an intimate look at the insurgent campaign of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the makers of this documentary stumbled upon one hell of a David. []

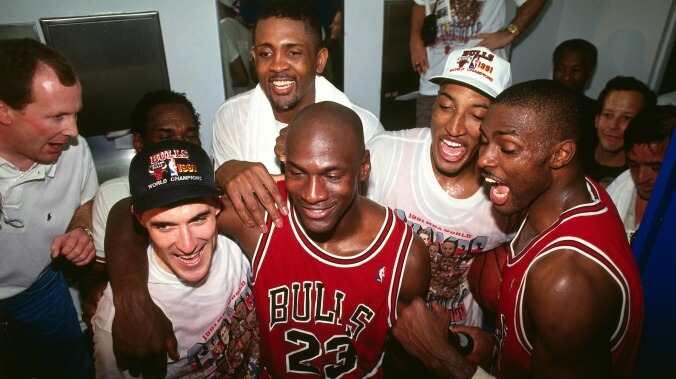

on the 1990s Chicago Bulls offers never-before-seen footage and talking heads interviews with a lot of really tall dudes. The series views the ’90s Bulls dynasty through the lens of the 1997-1998 season, the last time coach Phil Jackson and Michael Jordan, Scottie Pippen, and Dennis Rodman would all wear the red and black together in the United Center.

The Movies That Made Us tells behind-the-scenes stories about classic films alongside interviews with the cast and crew. The brief first season, which was released at the end of 2019, covered Dirty Dancing, Home Alone, Ghostbusters, and Die Hard, which is pretty much the exact four movies you’d choose for something like this. For , Disney probably wouldn’t let them do Star Wars, which means Raiders Of The Lost Ark would also be off limits, but we would be shocked if they made another season without Back To The Future, The Breakfast Club, or The Goonies. Maybe Aliens. Maybe a different Molly Ringwald movie. And hell, maybe Star Wars. Or, if they wanted to be overly clever about it, they could just do Die Hard 2, Ghostbusters II, Home Alone 2, and Dirty Dancing: Havana Nights. Surely those all had some kind of impact on people’s lives, right? [Sam Barsanti]

A massive part of Taylor Swift’s massive appeal is the notion that she’s an open book. Toward the beginning of Miss Americana, she describes the fan experience of listening to her records as “kind of like reading my diary,” after literally reading some of her old diary entries directly to the camera. Lana Wilson’s doc extends the metaphor: It’s intimate, specific, and presented—probably like most diaries—in a way that’s also lightly performative. Swift has always written her life story with an audience in mind. And if you’re going to tell your own story, naturally you’re going to tell the version you’d like to hear. Miss Americana focuses largely on the last few years of Swift’s career, providing just enough background to illuminate her outlook. Archival footage of early performances from when Swift was as young as 13 highlight an obvious talent who’s also doggedly eager to please, marking the beginning of the film’s arc. As a child, Swift either developed or discovered the dopamine rush of public praise, and it would prove to be the North Star of her professional life: “Those pats on the head are all I lived for,” she says, reflectively and with just a little regret. []

There’s no shortage of documentaries about the religious fringe, and they run the gamut from highlighting quirks to condemning criminal behavior. One Of Us spotlights a group that hasn’t faced the scrutiny of film crews quite so often as the likes of Scientologists or even Christian conservatives: Hasidic Jews. Rather than attempt an overarching portrait of the sheltered, rigid group, filmmakers Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady (who directed , so they’re no strangers to this type of story) follow three members who commit the unforgivable sin of stepping away from the religion. As with the Amish, who’ve been more exhaustively documented, leaving this ultra-Orthodox life doesn’t mean that you simply don’t worship anymore: You leave everything behind, including—in this film’s most compelling story—your children. []

It’s hard to feel anxious watching Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, based on the cookbook by chef and host Samin Nosrat. Nosrat is such a genuine, curious person, and loves food so much, that her energy is infectious. The show becomes more than a salve, encouraging viewers to take care in what they cook and eat, one of the greatest things you can do for yourself and others. It’s comforting to think about. [Laura Adamczyk]

Audiences don’t need to be familiar with or give a damn about Formula One racing to get drawn into Senna, a finely wrought documentary about Brazilian driver Ayrton Senna, known both for his incredible talent and his death at age 34 at the infamous 1994 San Marino Grand Prix. Senna is considered one of motorsporting’s greats, but Asif Kapadia’s film also makes it clear he was a sort of artist, his talent accompanied by an unquenchable thirst for excellence and a belief that racing offered him a connection to God. []

In Singapore of 1992, Sandi Tan and her two best friends decided to make an independent road film with their enigmatic filmmaking teacher Georges Cardona. Inspired by American independent auteurs of the era, their film, Shirkers, was poised to create a new national cinema. But at the end of filmmaking, Cardona absconded with the footage, never to be seen again. More than 25 years later, Tan recovered the footage (sans sound) and crafted a memoir-style documentary about the turbulent making of the film and its aftermath, effectively reclaiming it from the hands of her sociopathic mentor. While the story of Shirkers fascinates in its own right, Tan’s film also serves as a tribute to underground artists of yore. Tan and her friends, with their clandestine videotape syndicate and international zines, were countercultural pioneers when and where that still meant something. The Shirkers documentary feels as much like a handcrafted relic from another era as its original, lost-and-found inspiration, which makes its Netflix release all the more ironic. []

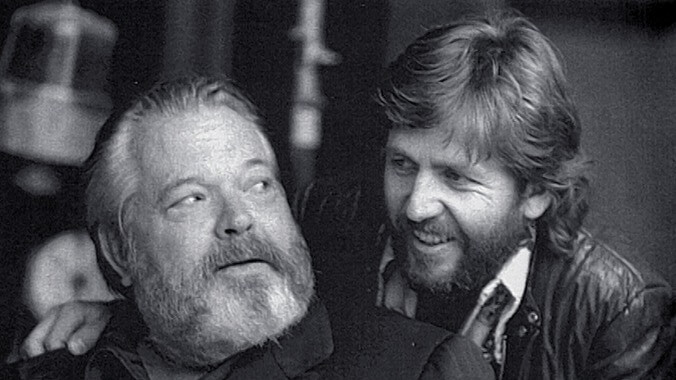

Morgan Neville’s documentary accompanied Netflix’s release of Orson Welles’ film The Other Side of the Wind and includes extensive interviews and outtakes from the roughly 100 hours of footage Welles left behind, offers a close look at The Other Side’s troubled, sporadic production, from its financing (which came in part from the brother-in-law of the Shah Of Iran) to the reshoots and recasting that became a necessity as filming dragged on and on. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

If this sounds similar to The Movies That Made Us, that’s probably because it served as the inspiration for that spinoff series. With three seasons now available, The Toys That Made Us dives into the creators and consumers of toys like Barbies, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Star Wars collectibles, My Little Ponys, G.I. Joes and more. Some origin stories are kids’ play, others led to all-out wars. Regardless, the series is fun to play with. [Patrick Gomez]

At its best, the first season of Ugly Delicious—Netflix’s globetrotting culinary documentary series from , Morgan Neville (), and others—took a dish, ingredient, or cuisine and used it as a jumping-off point for a bigger discussion about the world, all while remaining a solid food show. It was always the latter, but when it managed to accomplish the former, it became something really special. That was the case with “Fried Chicken,” the excellent sixth episode, which put Chang’s inquisitive mind and self-awareness to fascinating use. And it’s true, as a whole, of the show’s outstanding second season. []

For those of us born after 1975, the Vietnam War is not far enough in the past to feel detachedly academic, not recent enough to form a clear opinion on. What we know of the war is through its images and soundtrack: 16mm film footage of low-flying helicopters grazing the tops of rice paddy fields; the guitar line of The Youngbloods’ “”; . The Vietnam War, for the generation who didn’t live through it, is an abstract notion that hasn’t demanded our moral outrage. “No one wanted to talk about it.” So begins Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s magnum opus The Vietnam War. In talking about it now, a half century after the height of American involvement, Burns and Novick have engineered a staggering feat of filmmaking ambition, so overwhelming and raw it’s sure to rip open still-fresh scabs of those who lived through it. More importantly, it’s a film made for those born after, for whom their comprehension of that era—grainy snippets of late-’60s war iconography—will be supplanted by the incomprehensible tragedy of it all. []

With An Inconvenient Truth, documentarian Davis Guggenheim and former vice president Al Gore set out to save the world from an environmental cataclysm beyond the imagination of even Roland Emmerich. With his muckraking new exposé Waiting For Superman, Guggenheim wants to make sure we have a society worth saving. Having tackled global warming, he’s now moved on to another important issue: turning around a failing public-school system that should be the shame of our nation. Waiting For Superman surveys a grim academic realm where powerful teachers’ unions reward apathy and treading water, rather than innovative thinking or excellence, and the only test where American students consistently score high is on academic self-confidence. We aren’t No. 1, but we labor under the delusion that we represent the apex of academic accomplishment. With outrage, sadness, and compassion, Guggenheim examines the root causes of this public-school meltdown and offers suggestions for breaking the gridlock afflicting our educational system, most notably in the form of charter schools unbound by the institutional inertia that’s killing our schools. []

Upon introducing herself to Martin Luther King Jr., Nina Simone didn’t begin by telling him who she was, but rather who she wasn’t. “I’m not non-violent,” a stone-faced Simone said to America’s paragon of passive resistance. King smiled politely and told the esteemed jazz singer and pianist—one black civil-rights icon to another—that she was entitled to her position. So goes the story according to What Happened, Miss Simone?, director Liz Garbus’ visceral documentary set at the blind intersection between Simone’s prodigious musical talents and her polarizing political views. It’s among many stories in the film that sum Simone up as a complex, contradictory artist whose essence remains just out of reach, no matter how conventionally Garbus presents her. []

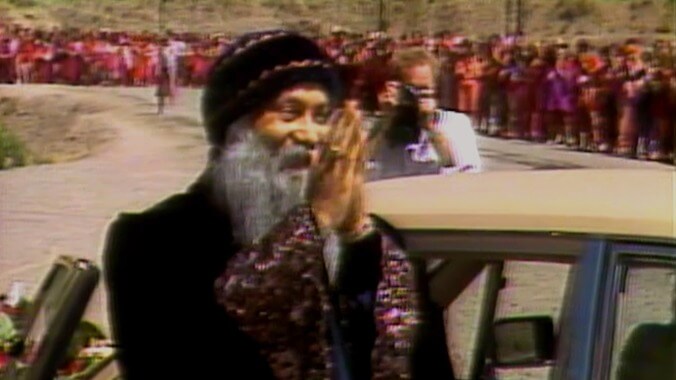

Watching the disciples of Indian guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh try to explain away the group’s involvement in everything from immigration fraud to attempted murder to intentionally contaminating salad bars with salmonella as a test run for a potential mass poisoning, you can’t help but wonder how these self-absorbed baby boomers’ quest for enlightenment got so tainted with myopia and greed. Wild Wild Country—a six-part documentary on the dark side of the utopian experiment that briefly took over the tiny town (think a few dozen people) of Antelope, Oregon in the early 1980s—is in part the story of a generational divide, a culture war between smug flower children who heap contempt on their less enlightened neighbors and scowling old folks deeply suspicious of anyone who deviates from their “God, guns, and red meat” lifestyle. It’s also the story of what happens when you create a religion with no consistent moral center, as Bhagwan did when he cherry-picked spiritual teachings from around the globe to justify his love of diamond watches, Rolls-Royces, and huffing nitrous oxide. []

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.