The best TV comedies on HBO Max

Streaming libraries expand and contract. Algorithms are imperfect. Those damn thumbnail images are always changing. But you know what you can always rely on? The expert opinions and knowledgeable commentary of The A.V. Club. That’s why we’re scouring both the menus of the most popular services and our own archives to bring you these guides to the best viewing options, broken down by streamer, medium, and genre. Want to know why we’re so keen on a particular show? Follow the links in each slide to coverage from The A.V. Club’s past. And be sure to check back often, because we’ll be adding more recommendations as shows come and go.

In the mood for something more dramatic? We’ve got you covered there, too.

Witnessing the chemistry between 2 Dope Queens hosts Jessica Williams and Phoebe Robinson, it’s hard to imagine that this partnership kicked off just a few years ago, after they met during a taping of The Daily Show. Williams was a correspondent for the satirical news show, while Robinson, a stand-up comic and TV writer, was an extra in one of her sketches. Robinson later invited Williams to join her onstage during her routine—as a birthday gift, no less—and the rest is podcasting history. []

The home improvement and hospitality shows that fill up HGTV and Food Network’s lineups seem to exist just to make us feel bad about our unfinished sanding projects and/or misshapen holiday cookies. As an avid watcher of programs like Barefoot Contessa and its public-access counterparts, Amy Sedaris has also found those standards set impossibly high, which is what makes her new TruTV series as refreshing as it is hilarious. In At Home With Amy Sedaris, the actor-comedian crafts a comedy that defies easy categorization, but is often as darkly funny as her previous hits like Strangers With Candy. []

The funniest show about an assassin having a crisis of conscience—or maybe the most heartbreaking show about an aspiring actor—HBO’s Barry is a masterclass in character work, which makes sense, since it’s about a guy (Bill Hader, the eponymous Barry) literally taking acting classes. Barry himself is great, and Hader does a good job generating sympathy for a guy who is a professional murderer, but the other characters he meets are just as interesting: Sarah Goldberg’s Sally Reed, another aspiring actor, struggles with exploiting and dramatizing her own personal experiences to help her career, and Anthony Carrigan brings surprising amounts of humanity to a semi-hapless Chechen gangster named NoHo Hank who idolizes Barry (for his murdering skills). []

To simply describe Betty as an expansion of Crystal Moselle’s 2018 film Skate Kitchen is to radically undervalue just how creatively transformative the series became in growing beyond its source material. While the film’s Altman-meets-Linklater sensibility is undeniably compelling, Betty takes everything that worked there and deepens it, mining rich veins of pathos, weighty social drama, and penetrating character study in equal measure. The young women navigating New York City’s male-dominated skateboarding subculture feel both idiosyncratically authentic and instantly relatable, which is testament both to the bond of their collective relationship and the inspired performances of the core group: Dede Lovelace’s Janay, Nina Moran’s Kirt, Ajani Russell’s Indigo, Racehlle Vinberg’s Camille, and Moonbear as the perpetually camera-wielding Honeybear. The intimacy of the storytelling and the relaxed hangout vibes suffusing the narrative belie the often heightened tensions lying just below the surface of these soulful skaters; there may not be any one central plotline (save for the steadily growing bond between five people who didn’t really know each other at the start, Kirt and Janay’s friendship notwithstanding), but there’s never a sense that the daily tribulations endured by our charismatic protagonists, no matter how fleeting, are anything less than riveting. []

In the “content” era, TV comedy increasingly feels like a way for networks to populate their YouTube channels and inevitably create some sort of podcast presence. Sketches are created to be shared without any larger context; scenes from sitcoms get turned into short videos to be shared. Late-night talk shows are competing to create viral moments that can become their own webseries. Narrative becomes irrelevant; there are only clicks. A Black Lady Sketch Show possesses a confidence in its first season that suggests the show is not interested in being chopped up into easily consumable chunks. A Black Lady Sketch Show seems more interested in creating a whimsical, loving world for its leads. The new sketch series offers up unfettered access to the minds of four dynamic women: Ashley Nicole Black, Quinta Brunson, Gabrielle Dennis, and the show’s creator, Robin Thede. []

From our : The hook of Aaron McGruder’s animated series is usually explained as the culture clash between the streetwise Chicago kids of the Freeman family and the whitebread mall culture of the suburbs. But that gets it tonally wrong: when Robert Freeman used his life savings to buy a home in the fictional suburb of Woodcrest, Maryland, he was doing it to get away from the hassles of the big city, and Woodcrest is almost always portrayed as accommodating at worst and downright nice at best. The real hook of the show is that it’s a vicious satire of black culture delivered from the inside; McGruder deliberately chose not to take the easy route by mocking the ’burbs for their unfunky sterility as so many people have done before, but to mock Huey and (especially) Riley’s inability to adjust to the fact that their new surroundings don’t force them to constantly struggle for survival. The idea that the white residents of Woodcrest recoil in terror at their new black neighbors was dropped almost immediately; instead, they’re indulgent of Riley’s gangsta poses and downright welcoming when rapper Thugnificent moves in. The only person who makes race an issue is Uncle Ruckus, a self-hating black character. And Huey’s biggest problem is that he’s accused of being a sellout by his Chicago homies, and doesn’t know how to cope with an environment free of “nigga moments.” Thus the satire works on a deeper level, suggesting that some people feel like outsiders in the suburbs because they’re making themselves that way.

Jonathan Ames (Jason Schwartzman) is a struggling writer who’s mostly unlucky in love. He decides to take a break from rejection and work as an unlicensed private detective, the better to avoid dealing with his own problems by zeroing in on other people’s. With only a Raymond Chandler book as his guide, he dives right into the seamy underbelly… of Park Slope. Things get more absurd and dangerous for the clueless dick, but he muddles through with the help of his friend Ray (Zach Galifianakis) and father figure George (Ted Danson). []

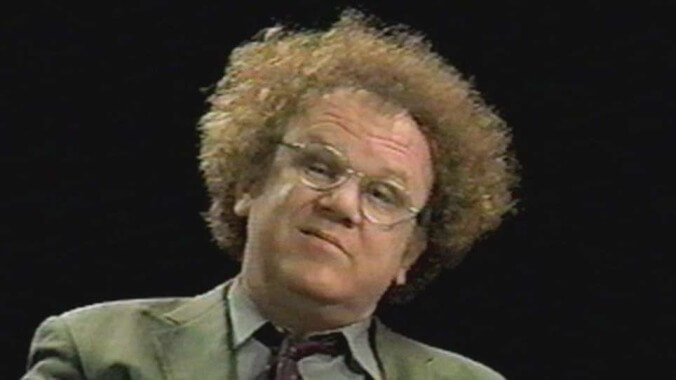

As Dr. Steve Brule, John C. Reilly remains funny on a surface level for his twitchy body language, bursts of guttural emotion, and constantly perplexed facial expressions. But beneath the physicality is a troubling psyche—the brain of a manchild who’s emotionally stunted, desperate to prove his own intelligence and masculinity, and—saddest (and funniest) of all—both intrigued by and scared to death of the real world. []

What’s it about? “The worst college in America,” a dubious honor worn as a badge of pride by the irresponsible, beer-swilling faculty at the University Of China, Illinois. It’s a place where the instructors want to party and the students want to learn, noble pursuits disrupted by time-traveling presidents, dunderheaded rock gods (at least one of whom is a legitimate deity), and a mountainous man-child in camouflage pants nicknamed Baby Cakes. It’s all held together by the high-minded crassness creator Brad Neely previously brought to “Cox And Combes’ Washington” and the Harry Potter fan dub Wizard People, Dear Reader.Why you should watch it: Because nobody on TV talks, sings, or holds a televised debate for department chairmanship like a Brad Neely character. The dialogue on China, IL is a singular gumbo of historical references, second-hand pop-culture riffs, and slang terms of the series’ own invention. (Professor Frank Smith is fond of “rat dicks” as a pejorative and an exclamation; Baby Cakes mixes Canadian whisky, maple syrup, and instant oatmeal into a treat he dubs “Canada Cake.”) Combined with a deep bench of supporting players (like Hulk Hogan as the school’s brawny dean) and the made-up commodities that litter the university’s landscape (King Drunk Beer, for one), the bizarro world of China, IL sets itself further and further apart with each passing episode. []

From 2011 through 2018, The Chris Gethard Show was the best party on TV, an inviting showcase for conceptual ambition, outrageous characters, and everyday people that wouldn’t have found a home anywhere else on the tube. Only the show’s third cable season (and single season on truTV) is streaming on HBO Max—so there’s no “,” unfortunately, but there is the one where dumpster episode guests Jason Mantzoukas and Paul Scheer are unexpectedly handed the keys to the Gethard Show kingdom with zero warning. It’s this one-of-a-kind series’ 26-episode swan song, a return to its high-wire, public-access, live-broadcast roots.

From our :While the original run of The Comeback, Lisa Kudrow’s cringe-comedy takedown of Hollywood narcissism, had a small but devoted following, it never inspired the kinds of feverish calls for a return engagement that, say, Arrested Development provoked. Sometimes, however, that time away, combined with the removal of the weight of expectations, can be a boon: When the series returned in 2014, it didn’t have to worry about fan service, or providing answers to lingering questions demanding resolution by loyal viewers. All it had to do was be funny. Which it did to delicious effect, the nearly decade of time between installments suggesting Kudrow and Michael Patrick King had been saving up great ideas all those years, just waiting to unleash them. Call it the Fury Road advantage: all that time away to plot and plan made the return that much sweeter. [Alex McLevy]

Six thirtysomething Londoners examine the steamy side of relationships in a show that’s like one of those innumerable Friends clones launched in the States in the ’90s, except, you know, good. Many on this side of the pond may only know Coupling from the deplorable American remake. Wipe the horrific memory of that sinking ship from the mind and embrace this witty, wonderful series. The show started out examining the relationship between Steve (based on show creator and writer Steven Moffat) and Susan (based on Moffat’s wife, producer Sue Vertue) and eventually branched out to develop an even more interesting relationship between self-deprecating Sally and arrogant Patrick. Sure, it’s reminiscent of Friends, but Coupling is a bit darker, and usually delves more deeply into sex than romance. Fans of How I Met Your Mother will appreciate the show’s experiments with concurrent plotlines and flashbacks. []

From our list of : At first blush, it sounds like an easy show to get into: a comedy about the fabulously wealthy crotchety man who created Seinfeld. But what makes Curb Your Enthusiasm more than just an amusing sitcom is that it forces its audience to accept a reality not quite similar to our own. Curb Your Enthusiasm might be set in the real world with real people, but it isn’t a realistic show; its people are driven by their ids, saying what’s on their minds and feeling so constrained by social niceties that they rip them apart like petulant children. Via creator/star Larry David, we root for a guy we’d probably want to punch in real life.

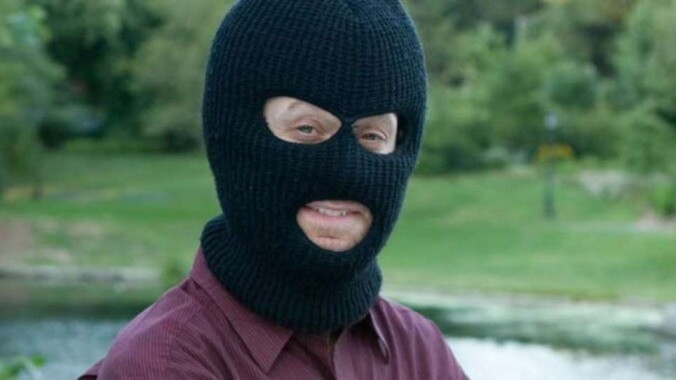

Adult Swim’s Delocated is the rare comedy show that succeeds both as a sitcom and as a premise-heavy sketch. It debuted in 2008 with a pilot, then launched as a series in 2009 with seven 15-minute episodes centered on a grand joke: A guy and his family are stars of a New York-based reality show, but they’re also in the witness-protection program, requiring them to wear ski masks and modulate their voices. The show quickly went off the rails, until “Jon,” played by show creator Jon Glaser, was the only one left lurking around with a balaclava. The show’s second season extended the format to half an hour per episode, and expanded Delocated’s world to include a cast of characters loyal to the dickish Jon, plus an entire Russian mob family out to kill him. It’s silly and self-referential (Eugene Mirman plays Yvgeny Mirminsky, a hitman/struggling stand-up comic), and fits perfectly between Parks And Recreation and Childrens Hospital on the TV-comedy spectrum. []

It likely won’t surprise you to hear this, given where it airs, but Eagleheart is seriously weird television. On many Adult Swim series, there’s a temptation to just let the weirdness stand in for good stories or good characters or even good jokes, but the best Adult Swim series—your Delocateds or your Childrens Hospitals—find ways to make the weirdness work within more traditional story structures. Delocated tells incredibly complicated stories with surprisingly well-realized characters (considering how many of them are in ski masks). Childrens Hospital may have the highest joke-per-minute ratio on TV, and a huge number of those jokes land. It’s not enough to just be weird; there’s gotta be something else behind the weirdness.For the most part, there is in Eagleheart, a sort-of-parody of action-packed cop dramas of the ’80s and early ’90s (apparently, the show was initially pitched as a more straightforward Walker: Texas Ranger spoof) that has mostly outgrown those initial trappings to become something all of its own. Even in the episodes that don’t work in the first season—and there are a handful of them—there are big laughs to be had, at least two or three times per episode. And in the episodes that do work, things keep getting weirder and weirder, but in a surprisingly logical way that almost seems to fit the show’s goofy universe. []

From our list of : HBO’s Eastbound & Down doesn’t entirely fit in with the “comedy of discomfort” scene epitomized by the British Office and Curb Your Enthusiasm, nor is it as broadly farcical as other projects featuring its star, Danny McBride. Instead, it finds a sweet spot between outlandish and authentic. McBride plays a washed-up baseball player, Kenny Powers, who has none of the fans he once did, yet retains all of his swagger. He’s a chauvinist pig and the ugliest of ugly Americans, and Eastbound at first invites viewers to laugh mostly at him, but the six-episode first season—half of which was directed by indie auteur David Gordon Green, tellingly—also allowed audiences to feel a little sympathy. Even though Kenny Powers says things like “I’ve been blessed with many things in this life: an arm like a damn rocket, a cock like a Burmese python, and the mind of a fucking scientist,” he’s hard not to love.

From our list of : When HBO announced that it was building a sitcom around the New Zealand folk-comedy duo Flight Of The Conchords, many doubted whether what was essentially a musical act would translate well to filmed, scripted comedy. But the series has shown unique strengths: Jemaine Clement and Bret McKenzie are able to play low-key in front of a camera, toning down their stage personas to a pleasantly awkward degree. And by arranging for support from a wide range of alt-comedy stars (Kristen Schaal, Aziz Ansari, Eugene Mirman, Demetri Martin and others), they concocted plenty of situation for their comedy. Flight is also delightfully New York-y, with lots of charming location shots to augment the scenes shot in the duo’s cramped pad. The show went a bit too broad in its second season, but even when the comedy faltered, there was always a winning song just around the corner.

Here is a sentence that is inarguably bizarre without context: Every Fresh Prince fan should feel indebted to the Internal Revenue Service.Here is a sentence that may sound even more far-fetched: The Fresh Prince Of Bel-Air was one of the most subversive network sitcoms of its time.Regarding that first improbable sentence: When Will Smith met music producer Benny Medina, Smith had already won the first Grammy awarded in the rap category as part of the duo DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince. He had already made a fortune. But Smith was particularly receptive to Medina’s pitch—that he star in a television show based on the producer’s childhood move from Los Angeles’ Watts neighborhood to Beverly Hills—for one simple reason: He had already spent a fortune, too, and he neglected to send the government its share of his earnings. Smith was nearly bankrupt after the IRS assessed his unpaid taxes at $2.8 million. The show was a shot at solvency, and Smith’s wages were garnished 70 percent during the first three seasons to pay his back taxes.Medina and his partner Jeff Pollack capitalized on Smith’s eagerness for a steady paycheck and brought him to see Quincy Jones, who wanted to produce a sitcom starring the charismatic MC. “He told everyone from NBC, ‘Listen, I got your next star. I need you to come to my house after the Soul Train Music Awards.’ So everyone went to his house,” Smith told James Lipton in an episode of Inside The Actor’s Studio. The details of Medina’s childhood were fuzzed to match the star’s biography. The main character would also be named Will Smith, and like Smith, he would be “born and raised” in West Philadelphia. According to Smith, nobody asked him if he could act before the deal was signed. He did not know how; in his first scenes on the series he is clearly mouthing along with other actors’ lines.Smith treated Fresh Prince like an acting bootcamp, and his lack of experience didn’t hamper the show. NBC put the fledgling actor front-and-center from the beginning and let his charisma compensate until his acting caught up. []

Before the dawn of the 1994 TV season, networks were declaring that fall to be the year of the “family.” Building off of Urkel-related horrors like Family Matters, many TV creative powers were aiming to capitalize on the familial mindset with relatives-based series: Margaret Cho’s All-American Girl, Steve Harvey’s Me And The Boys, and not one but two shows that featured orphans trying to raise themselves and stick together: On Our Own and Party Of Five.As it turns out, 1994 was the year of some kind of family, but an unconventional one, as TV legend James R. Burrows was one of the few who foresaw the Friends explosion. Pilot director Burrows—who knew sitcom ensembles from his work on The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The Bob Newhart Show, Taxi, and Cheers, among many others—knew that the magnetic chemistry of the cast was going to be the show’s main draw. At a Hollywood event in his honor [in 2013], Burrows recalled, “I said to Les Moonves, who was then running Warner Bros., ‘Give me the plane—I want to take the six kids to Vegas to talk to them.’ It was me and the six of them, and I said, ‘This is your last shot at anonymity.’ I knew that this show had a chance to really take off.”Friends did more than take off: It changed the sitcom landscape by breaking from many typical formats. The show did not revolve around a family home or a workplace, but a makeshift clan that seemed familiar to Gen Xers who were forming their own similar connections. The six twentysomething stars were so young that network execs initially suggested an “older mentor type” to give the show’s opinions more weight. The first sitcom not to feature any sort of authority figure (i.e., parent or boss) was The Monkees, which debuted in 1966 (I like this parallel because Matthew Perry’s delivery always seemed rather Dolenzian). Hip young sitcoms of earlier eras usually featured young couples (Bridget Loves Bernie, He & She), en route to eventually starting their own families. It’s safe to say that before Friends, the youth sitcom was far from as prevalent as it is today (although Living Single, a sitcom about six African American friends living in Brooklyn, preceded Friends by a year). []

From our : For the last decade or so, every hard drive I’ve owned has had 3 GB dedicated to Adam Reed and Matt Thompson’s Frisky Dingo, the ultimate in viewing pleasure for a brain addled by strong drink or weak immune system. Looser and weirder than Reed’s later Archer, it has a lot to offer the under-the-weather watcher: It’s short (the entire series is only about four hours long), funny as hell, and the rhythmic, callback-heavy dialogue can produce an almost hypnotic effect, as the various “Boosh”es, “What the hell damn guys,” and references to Hooper slowly lull you into a sort of pleasant nonsense trance.” [William Hughes]

Composed of equal parts wacky small town show, family comedy, and sweetly observational romantic comedy, Gavin & Stacey is the antithesis of most TV shows. On most TV shows, there would be more of an emphasis on the impossible odds the central couple faces in making their lives work, and Gavin would work at a wacky radio station or something, and the two would have a whole army of cute, adorable kids. The temptation with a scenario like this is to just keep tossing crap at it until it feels more like a TV show. There’s really no high concept to the series. What there is to the show is pretty much the very slight idea at its center: A boy and a girl fell in love, but they lived a long way apart—in different worlds, really—and in the course of trying to make their relationship work, they realized that you can’t leave your old life behind as comfortably as you might like.Gavin & Stacey is only going to work for you if you can buy, well, Gavin and Stacey. The two could be annoyingly cutesy (and, indeed, are written as such at times), but the show has a healthy sense of just how much is too much and when we’ll be rolling our eyes, instead of finding their banter enjoyable. It helps that Matthew Horne and Joanna Page make such a believable couple at the center of the show. You can buy that these two fell in love and fell hard without really thinking through the problems that might result, that their connection would keep pulling them back together again and again, even as their old lives might attract them as well. Horne’s appealingly blank face and go-getter manner mesh nicely with Page’s, for lack of a better word, spunk, and the series turns such small stories as having sex two times a day to be sure you conceive a child into things that feel emotionally involving. []

“You did good, ma’am,” says Niecy Nash’s no-nonsense nurse DiDi to an elderly patient after she gives a little push and releases her bowels all over another nurse’s face. “You did real good.” With her compassionate dialogue, patient deliveries, and award-worthy side-eye, DiDi exemplifies the spirit of Getting On. She’s not unflappable. She’s just quiet. She takes a moment to collect herself before speaking when her sister-in-law gets on her nerves. At her angriest she sarcastically asks whether it’d be better to bounce a patient to a negligent nursing home or throw her out on the street. The show has the stakes of ER and the slapstick of Jackass, but Getting On is defined by its calm. No matter how grave or raucous it gets, Getting On keeps the volume down so it doesn’t needlessly disturb anyone. It’s the most peaceful show on television. []

A cringe-comedy character study too often mistaken for a treatise on the entirety of millennial culture, Lena Dunham’s HBO series presented an unglamorous flip side to the Sex And The City fantasy. In both its strengths and its weaknesses, Girls became a lightning rod for contemporary feminist discourse. Yet from its realistically awkward portrayals of sex to its willingness to unapologetically revel in the worst impulses of its leads, the influence of Girls lives on in just about every dramedy that’s followed. []

Many hangout sitcoms have tried to replicate Friends’ cast chemistry and, let’s face it, ratings success. Happy Endings certainly never achieved said ratings success, but the chemistry between its cast remains one-of-a-kind to this day. Unlike Friends, the series openly acknowledged how its characters were terrible people, all in the name of “pile-ons.” Beginning with the rather generic premise of what happens in a friend group when two of your friends have a massive breakup, Happy Endings was quick to reveal its rapid, obscure-pop-culture-reference-heavy style of comedy, whether you watched it in order or not (thanks, ABC). As far as the ratio of jokes per minute, no sitcom has been able to touch Happy Endings since it went off the air. []

It’s easy to forget in the age of Rick And Morty, Too Many Cooks, and Family Guy reruns, but the original Adult Swim lineup was almost entirely based around plucking characters from Space Ghost: Coast To Coast or obscure Hanna-Barbera cartoons and dropping them into new TV genres. The Brak Show was a family sitcom, Sealab 2021 was a workplace comedy, and Aqua Teen Hunger Force was sort of a stoner hangout show (a glimpse of Adult Swim’s future), but none of them committed to this conceit as thoroughly as Harvey Birdman, Attorney At Law. As indicated by the name, it was a parody of legal dramas that happened to star the guy from Birdman And The Galaxy Trio—a ’60s action cartoon about a guy with wings who can shoot beams out of his hands.The Adult Swim show was created in 2000 by Michael Ouweleen and Erik Richter, and it takes place a few decades after the events of the old cartoon. In the years since his turn as superhero, Birdman (whose real name is now given as Harvey Birdman) has taken a job as a defense attorney at a law firm run by his old superhero associate Falcon 7 (now Phil Ken Sebben), with most of the other attorneys he faces being villains from the old show and most of his clients being the stars of Hanna-Barbera cartoons from the studio’s heyday—think The Jetsons, Scooby-Doo, and deeper cuts like Speed Buggy.While other early Adult Swim shows rejoiced in absurdity, Harvey Birdman was a love letter to both the tropes of legal dramas and an entire generation of cartoons that some younger viewers might not have even been aware of. That’s not to say Harvey Birdman wasn’t absurd, as it was built on a structure of running jokes and callbacks that would become increasingly nonsensical as seasons went on. One early episode featured a miniature clown car popping out of a character’s mouth, after which the car could regularly be seen driving around the courtroom or popping out of other unexpected places. Then, in the finale, a big villain destroys a clown-car factory as a direct acknowledgement of the weird little gag. []

The Heart, She Holler is less a comedy show than a feeling—an aesthetic. It’s still funny, but pushes the mind to strange and unsettling places that sit peripheral to comedy, like gleefully making numerous outrageous jokes about incest; sometimes you don’t know where the laughter’s coming from, but it’s there. Not surprisingly, the show is from the minds of PFFR, the collective known for Wonder Showzen, Xavier, and Delocated, each at varying degrees of groundedness. (In the non-PFFR world, think Tim & Eric as the most obvious example, or to a lesser extent Jon Benjamin Has A Van.) Sometimes these shows are best appreciated when you sit back and marvel at how they’ve turned something simple into something fucked up with only a few minor tweaks. []

Beyond a bump in production value, Ben Sinclair and Katja Blichfeld’s webseries hasn’t fundamentally changed since HBO picked it up in 2016. And that’s because High Maintenance was, from the beginning, delivering compassionate, must-watch experiments in storytelling. The sense of connection the show builds in glimpsing so many different New Yorkers’ lives, all threaded together by their cannabis dealer, The Guy (Sinclair), is a humanizing, mind-expanding experience we hope to sustain well into the 2020s. []

Navigating adolescence through the lens of his video camera, the preteen protagonist of Home Movies shares a name, a voice, and presumably some life experiences with the show’s mastermind, Brendon Small. But this four-season cult cartoon, born on UPN and raised in the more permissive household of Adult Swim, belongs equally to its co-creator, Loren Bouchard. There are telltale signs of both writers’ involvement over four stellar seasons. The elaborate movie homages and rock operas dreamt up by the fictional Brendon feel like dry runs to the power-chord insanity of the real Brendon’s Metalocalypse. Likewise, the show’s vision of precocious childhood anticipates the more refined pleasures Bouchard now offers with Bob’s Burgers. But Home Movies is its own animal, heavy on inspired improvisation and featuring characters as richly developed as they are crudely drawn (first in Squigglevision, then through a marginally more attractive Flash animation). And with all due respect to Sterling Archer and Bob Belcher, H. Jon Benjamin’s definitive vocal performance may still be his embodiment of ill-tempered peewee soccer coach John McGuirk, the most uproarious of this show’s young and old screw-ups. []

One of [2020]’s sweetest and strangest shows combines the esoteric beauty of an avant-garde documentary with the comic whimsy of a late-night TV “man on the street” sketch. Host and narrator John Wilson has apparently spent years obsessively recording and annotating his daily life in and around New York City. For How To, Wilson and his co-writers Michael Koman and Alice Gregory have assembled some of those video clips and observations into remarkable autobiographical journalism, presented in the form of self-help tips, delivered in a halting voice. Wilson has a knack for visual gags, drawing on his archive of images to find the perfect images of urban absurdity to illustrate—and sometimes undermine—his points. Whether he’s contemplating the deeper meaning of scaffolding, wondering why it gets harder for people to make friends as they age, questioning the reliability of his own memories, or documenting a city transformed by a pandemic, Wilson ultimately looks at life on a touchingly human scale, trying his best to put a hopeful spin on whatever horrors and wonders he captures within his camera’s frame. []

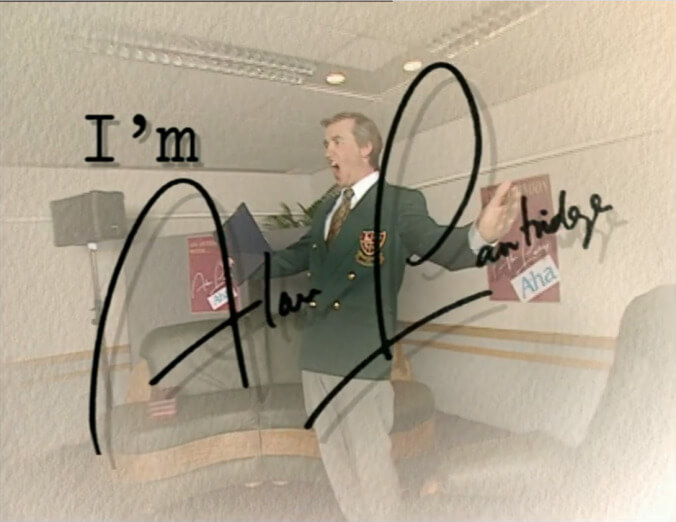

A sublime creation, [Alan] Partridge (Steve Coogan) is a self-styled guardian of showbiz traditionalism, beset on all sides by people who want to push political or social agendas. Partridge is also a narcissist and a bumbler, convinced that he’s more popular and beloved than he actually is, and thus prone to career-threatening gaffes. In I’m Alan Partridge (co-created with Peter Baynham and Armando Iannucci), we see Partridge after he’s been drummed out of the BBC and forced to regroup in his hometown of Norwich. The extension of the Partridge story to his off-camera life proves to be a stroke of genius, showing (as The Larry Sanders Show did around the same time) how difficult it is for even a small-time celebrity to muddle along in the real world. []

Issa Rae’s confident, creative series follows leads Issa and Molly as they navigate late-twentysomething life in Los Angeles. Issa’s electric, straight-to-camera raps may be the show’s trademark, but its considered look at Black female friendship is what sets Insecure apart. Whether exploring Issa’s search for self-expression, Molly’s relationship struggles, or the micro-aggressions both face in their workplaces, Rae and her team bring honesty and humor to an experience all too often overlooked on American TV. []

“And just like that, I can feel my soul grow back.” So says Joe Pera at the end of “Joe Pera Takes You On A Fall Drive,” the third episode of Joe Pera Talks With You. It’s a fitting capper to 11 minutes that find Pera—playing a fictionalized version of himself who teaches choir in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula—taking part in a favored autumnal ritual. It’s also an apt summary of what it’s like to watch Joe Pera Talks With You, undoubtedly the most placid program to ever air on Adult Swim, not counting the two specials the New York-based comedian made for Cartoon Network’s typically anarchic late-night block in 2016. Everyday life is so loud and so abrasive, and Joe Pera Talks With You provides a soothing balm to all that.None of which is to say that the show isn’t funny; it is, often uproariously so. But it’s a particular type of funny, of the soft-spoken, deadpan, and disarming type that Pera practices onstage and on the talk-show circuit. It’s one of his many gifts as a performer, the way his understated wardrobe, deliberate delivery, and nervous body language set an expectation for awkwardness, before Pera pulls the rug out from under the audience with the confidence of his pacing and the precision of his writing. Joe Pera Talks With You is formatted along the same lines, with the everyday topics in the episode titles serving largely as windows into Joe’s weird little world, which reminds me in all the best ways of The Adventures Of Pete & Pete, the humor writing of Jack Handey, and the films of Wes Anderson. (Other works Joe Pera Talks With You makes me think of: Fishing With John, The Joy Of Painting, Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood.) “Joe Pera Takes You On A Fall Drive” is about so much more than an afternoon spent inside Joe’s 2001 Buick Park Avenue, but to say too much more would ruin the joy of watching the thing unfold. []

From its opening sketch exploring performative Blackness and masculinity to its devastating final sketch, a musical trip to “Negrotown,” Key & Peele uses every tool in the comedy toolbox to explore and comment on American culture. Pointed political satire, detailed character work, pop culture homage, broad physical comedy, unabashed silliness, and strange flights of comedic fancy, this series has it all. Yes, it’s ridiculously funny, with an incredible hit-to-miss ratio. Yes, it features strong performances from Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele and impeccable direction from Peter Atencio, not to mention the best hair and makeup in sketch TV. What’s most impressive, though, is the versatility and depth of its writing, giving audiences some of the decade’s most indelible comedic characters. It’s most definitely our shit. []

Steve Coogan and Patrick Marber created the BBC TV series Knowing Me Knowing You With Alan Partridge in 1994 in part as a mockery of the kind of show-business personality who’d be sorry to see variety shows go. Coogan’s fatuous chat-show host Alan Partridge is the sort who thinks he’s hip because he owns a David Bowie album, but he packs his half-hour program with as much old-fashioned, fun-for-the-whole-family entertainment as he can work in between the strained celebrity interviews and self-promoting stunts. As Partridge, Coogan is so dense that it’s almost not funny. The comedy comes from seeing Partridge’s vision of retro fun go awry: the alluring dance troupe he books turns out to be a bunch of gay men, the clown act is vulgarly avant-garde, his celebrity guests talk more to each other than to the host, and so on. It’s a keen explication of how the variety format, turned a notch off-center, can go from surreal to frankly nightmarish.[]

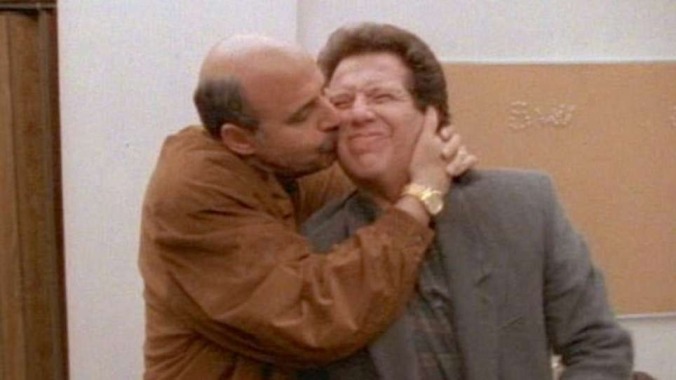

What it’s about: Against an ever-shifting late-night talk-show scene, veteran TV host Larry Sanders (Garry Shandling) struggles to keep his footing in the face of fickle audiences, threats from new faces, and the demands of network weasels. He also has to find the right balance between appeasing the correct people to keep his career afloat and fulfilling his own desires.Why you should watch it: Everyone’s heard that you should write what you know, and the razor-edged Larry Sanders is the funniest insider satire of TV imaginable. (It was conceived by Shandling at a time when he really was being courted by the networks as a possible late-night host, and although he had no intention of taking such a job, he kept public speculation over his career plans alive in order to generate publicity for the show.) Larry Sanders is also a time capsule buried at the nexus point where just about every ’90s new-style comic and show-business maverick making a name for themselves in the came together: Rip Torn, Jeffrey Tambor, Janeane Garofalo, Jeremy Piven, Bob Odenkirk, Mary Lynn Rajskub, Scott Thompson, and Sarah Silverman all had regular or recurring roles on it at one point or another. []

Looking used its central character, Patrick, an uptight, often unlikeable WASP played by Jonathan Groff, to explore a larger community of gay men in a rapidly gentrifying San Francisco. The series’ characters navigated the consequences of their youthful indiscretions, struggled to maintain their relationships, and dealt with a world that had suddenly decided they should be like everyone else. Throw in Andrew Haigh’s visual influence and some stellar performances, and you have a show best described as “tender.” []

A bone-dry comedy for anyone who ever sat in front of a TV trying to conjure a showing of Beetlejuice, Los Espookys arrives like a tall glass of cold water garnished with a prop eyeball. Created by Fred Armisen, Saturday Night Live wunderkind Julio Torres (he of “Wells For Boys” and “Papyrus”), and Ana Fabrega, the show concerns a quartet of friends who form a “horror group,” channeling their interests in monster movies and creepy prosthetics into a hustle that promises to break them out of lives defined by expired cellphone minutes, dental-assistant drudgery, and barely tolerating their statuesque boyfriend while waiting around to inherit their parents’ copyright-flouting chocolate empire. It’s a deadpan daydream written and performed primarily in Spanish (with English subtitles, which switch to Spanish subtitles for scenes in English), set in an imaginary, unnamed Latin American country. The handmade look and understated punchlines recall another HBO comedy about realizing creative ambitions on a shoestring—though Flight Of The Conchords never featured a parasitic demon who’ll only divulge their host’s secret past after getting to watch a middle-of-the-road Best Picture winner. []

When The Middle first arrived on ABC in the fall of 2009, the two biggest things the series had going for it were its leads: Patricia Heaton, returning to the familiar groove of a family-oriented sitcom (her previous endeavor, Fox’s Back To You, teamed her with Kelsey Grammer, the pair of them playing local news anchors in Pittsburgh), and Neil Flynn, finally getting a chance to play someone other than the janitor on Scrubs. Also important, if not as immediately known to viewers, was that the series’ creators, DeAnn Heline and Eileen Heisler, came with a major cache of comedy credits to their names, including Kate And Allie, Doogie Howser, M.D., and Murphy Brown. What proved to be the most valuable experience in their back catalog, however, was the time the duo spent working on Roseanne, a show that managed to find humor in the struggle to make ends meet.Frankie and Mike Heck, the characters played by Heaton and Flynn on The Middle, are definitely cut from the same mold as Dan and Roseanne Conner. Mike’s a blue-collar guy who goes to work, gets paid, comes home, and enjoys life’s simple pleasures when he’s not being annoyed by his kids. Frankie tries to be the best mom she can, but she also has a full-time job, which means that she gets just as annoyed by the kids as Mike does. Still, they do their best, although it’s sometimes a struggle to deal with the disparate personalities of their daughter and two sons. []

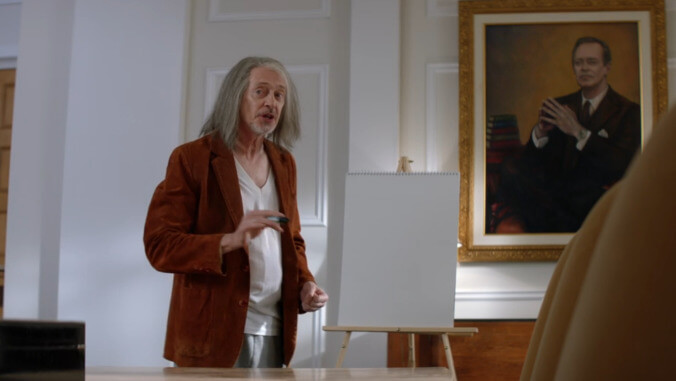

“Steve Buscemi is God” is probably enough of a pitch to land you a meeting with at least one development executive, but Simon Rich’s Miracle Workers is actually based on his novel, What In God’s Name. The high-concept series envisions heaven as a large, stagnant corporation, with Buscemi as an all-powerful deity who can’t remember if he lost his passion for his work before his ability to do it, or vice versa. But rather than reinvest in his creation, God decides he’s just going to start over—this time, with a restaurant idea so bad that even the sycophantic Sanjay (Karan Soni) can’t play along. Enter Craig (Daniel Radcliffe, who also executive-produces) and Eliza (Blockers breakout Geraldine Viswanathan), two angels in the Answered Prayers department who try to stave off the end of the world by betting God they can make a couple of socially inept humans (Sasha Compére and Jon Bass) fall in love. It’s a thoroughly absurd premise, and one that might struggle to connect with viewers. But just as he did with Man Seeking Woman, Rich uses these far-fetched notions to make witty and moving observations about love and devotion. []

Mr. Show always had something to say regardless of a sketch’s gag-reflex quotient, a satirical edge that dug into corporate greed, political overreaches, religious hypocrisy, meaningless showbiz awards, condescending advertising, lowest-common-denominator entertainment, and nearly indistinguishable blends of mustard, mayonnaise, mustard-mayonnaise, and mayonnaise-mustard. The show was well-versed in TV and cinema vocabulary, building comic worlds within news broadcasts, ride-along crime shows, grainy footage of megaphone crooners, and one family’s epic journey toward slightly discounted tube socks. In the grand Python tradition, it was deeply silly, though there were no fourth-wall-breaking conventions to punish characters for being silly. (The events of the sketches usually took care of that.)And Mr. Show was funny. God dammit was Mr. Show ever funny. Scene by scene, but also episode by episode, which meticulously stitched together (sometimes, by the creators’ own admission, in an overly fussy manner) their component parts with shared themes, linking segments, and last-second segues. YouTube and other video-sharing sites have helped to keep certain Mr. Show sketches in the cultural conversation—particularly when our reality mirrors one of its whacked-out fictions—but this view of the show misses the forest for the trees, and the following list celebrates Mr. Show for what it could accomplish in a half-hour timeframe in addition to four- or five-minute chunks. Because if you don’t watch “God’s Book On Tape” and its flying limousine punchline, you have no context for the flying limousine that turns up in the ancient scrolls shown at the beginning of “Monster Mash.” []

It was inevitable that someone would parody the wealth of business makeover series flooding the airwaves, but who knew that the result would be this? Across four seasons, Nathan Fielder used gags involving poo-flavored yogurt and Holocaust-denying outerwear companies to make resonant points about commercialism, virality, and the extremities of politeness. But it wasn’t the pranks themselves that made the show so much as Fielder, whose vulnerability and general air of desperation tended to either disarm his subjects or unnerve them, resulting in shocking glimpses of humanity both kind and cruel. A bow atop it all was its stunning feature-length series finale, “Finding Frances,” in which Fielder confronted the show’s blurry fourth wall during a road trip in search of a friend’s lost love. []

She had style, she had flair, but she was where? Nowhere to be found in the streaming universe until HBO Max came a-calling for the six seasons Fran Drescher spent dressing to the nines and flexing her nasal whines as the flashy girl from Flushing, nanny Fran Fine.

Creator Kari Lizer (an ’80s Hollywood ingenue and ex-Matlock co-star who transitioned from acting to writing in the ’90s) began The New Adventures Of Old Christine with a simple, character-driven premise, inspired by her own experiences as an overextended working mother. The show’s name introduced its “hook,” which was that, post-divorce, Christine’s (Julia Louis-Dreyfus) ex-husband Richard (Clark Gregg) was shacking up with a younger woman also named Christine (Emily Rutherfurd). From the start, the plots were always driven by “Old Christine” trying to juggle raising a son, owning a small gym, and finding her own romance—all while shrugging off the snide comments of her neurotic brother/roommate Matthew (Hamish Linklater) and laid-back best friend Barb (Wanda Sykes). As the series evolved, Lizer and her writers moved away from the network’s clumsy early advertising pitch for a show about a middle-aged woman trying to compete with younger ones, and instead built more jokes around the idea that while all of these people were fundamentally screwy, none were as messed up as the title character. []

The Office is the most influential TV comedy of the last 10 years and probably the most influential TV comedy since Seinfeld. You could make an argument for Friends or Arrested Development or the U.S. remake of the show or even Everybody Loves Raymond, but most of those shows were reacting to Seinfeld or trying to ape what made this show so great. In just 14 episodes, Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant took the standard workplace sitcom—full of will-they/won’t-they romances and wacky hijinks—and brought it slightly more down to Earth. They brought cringe humor into the TV mainstream in a big way. They invented a set of characters that resonated from the very first episode, and they create a full story that leaves at just the right point in time—twice. []

Even though it premiered all the way back in January, The Other Two was one of the biggest surprises of all of 2019. Instead of going the obvious route—with Brooke (Heléne Yorke) and Cary (Drew Tarver) resenting famous younger brother ChaseDreams (Case Walker), Pat (Molly Shannon) being a stage mom caricature, or Chase being a secret monster—The Other Two ended up being a satire with a ton of heart. In fact, only Schitt’s Creek would challenge it on the comedy and heart front this year, and it could go either way. (While The Other Two won out here, we’d still love to see vs. in a battle to the death.) The Other Two’s first season was impressive in its confidence and self-assuredness, in its automatic understanding that edginess and whip-smart don’t have to come from a negative place; they can still exist without being sappy or toothless. []

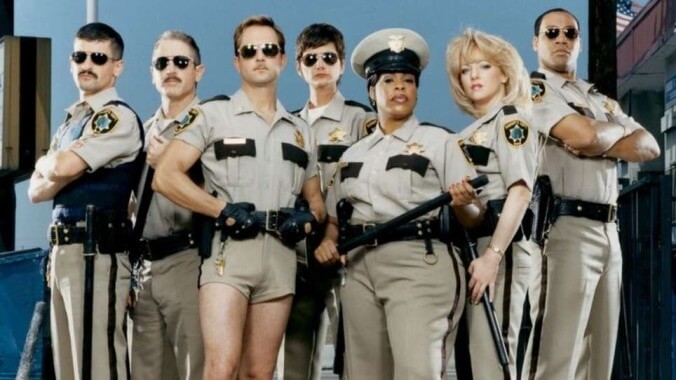

When crime rears its ugly head in Reno, Nevada, the men and women of the Reno Sheriff’s Department are… not exactly on the case, but certainly somewhere near it, probably working through their own petty disputes in the squad car. Created by The State alumni Ben Garrant, Thomas Lennon, and Kerri Kenney, Reno 911! parodied the run-and-gun look of Cops, in a improv-driven format fit for a rogues’ gallery that eventually included Paul Rudd, Keegan-Michael Key, Patton Oswalt, Nick Kroll, and many more.

Springboarding from a deliberately lowbrow comic concept (what if Back To The Future, but gross and mean), Justin Roiland and Dan Harmon’s animated universe quickly expanded to encompass the deepest reaches of scatological hilarity, existential dread, and Grant Morrison-worthy sci-fi weirdness. Roiland voices both Rick Sanchez (the universes smartest—and thus most contemptuous—mad scientist), and Morty (Rick’s painfully ordinary 14-year-old grandson/sidekick), while Community creator Harmon’s infamously Rick-like genius helps cantankerously steer the duo’s cosmic adventures in mind-bending rings around both sitcom convention and sci-fi cliché. Roping his extended family into schemes involving multiple realities, multiple Ricks, and yawning, nihilistic despair, Rick is both Roiland and Harmon’s celebration and deconstruction of the loneliness of ultimate genius, while still finding room for the occasional genocidal musical fart. []

The Righteous Gemstones is the best of the three Danny McBride collaborations with Jody Hill and David Gordon Green. It’s the story of a wealthy, powerful evangelical family that explored ideas of family dynamics, faith, greed, and fame. The Righteous Gemstones gets top-shelf performances from its stellar cast: Walton Goggins as the sly, foul-mouthed uncle who wants in on the riches; John Goodman as the soulful but intimidating patriarch who’s become unmoored since his wife died; Edi Patterson as the insecure, conflicted outcast of the family; and McBride himself, who brings a certain gravitas to the show’s look at father-son relationships. The Righteous Gemstones struck the perfect balance between comedy and drama. []

The promos for Search Party didn’t inspire confidence: Some self-involved Manhattan twentysomethings led around by Alia Shawkat seek a fellow millennial (who they barely know) who’s gone missing. But executive producer Michael Showalter showed again why he’s so very good at what he does. He and writers Sarah-Violet Bliss and Charles Rogers crafted a riveting mystery, in which the Greek chorus of these narcissistic investigators (Meredith Hagner and John Early) offered much more mirth than annoyance. Vets like Parker Posey and Ron Livingston are always going to bring it, but Shawkat was an out-and-out revelation. As her Dory became obsessed with the disappearance, it became more difficult to accurately gauge the level of danger she was in. []

Before it ever hosted Lena Dunham and her coterie of Girls, HBO aired the weekly misadventures of the thirtysomething women of Sex And The City. In 1998, Darren Star adapted Candace Bushnell’s eponymous collection of essays that had originally appeared in The New York Observer under the pseudonym Carrie Bradshaw, which became the name of the series’ lead, insomuch as it had one. Sex And The City’s focus covered a quartet of Manhattan single ladies, but as our narrator, Carrie was the linchpin. And as Bushnelll’s stand-in, the fashion- and men-savvy fictional columnist began the series as the most relatable member of the group, a premise that became harder to fathom the longer the show went on.The series would vacillate between rom-com, dramedy, and scintillating comedy genres over the course of its six-year run. It’s pretty much an established fact that things got off to a rocky start in season one. The voice-over narration, which lingered throughout the series, was more intrusive early on, and Carrie sounded far too smug for the quality of puns she was delivering. And the fourth-wall-breaking bits were a little too silly (think Saved By The Bell’s time-outs) for a series that ostensibly featured second- and third-wave feminists. Those details were ironed out by the time the show really gained traction, which was right around when HBO’s original programming did. []

An unassuming app developer with a game-changing algorithm, Thomas Middleditch’s Richard Hendricks served as an ideal vessel for the profane, tech-centric satire of HBO’s Silicon Valley. What Mike Judge’s series lacked in surprise—each season more or less played out the same—it made up for in the timeliness of its humor, which targeted everything from VR, AI, and MMORPGs to cryptocurrency, venture capital, and overconfident bros adept at little more than failing upwards. []

Even South Park acknowledged that The Simpsons did it first, but Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s creation has had a consistency The Simpsons should envy, and it’s long eclipsed other graying workhorses like Saturday Night Live when it comes to topical satire. It’s safe to say the younger generation has derived more of its sense of humor from South Park than any other cartoon—and quite possibly, any other show. []

Space Ghost Coast To Coast was an unlikely candidate to lead a TV revolution. Tasked by Ted Turner with creating a late-night animated series that appealed to adults, Cartoon Network executive Mike Lazzo dug into the Hanna-Barbera archives and refashioned the lead of CBS’ Space Ghost And Dino Boy into a clueless talk-show host. Space Ghost Coast To Coast debuted in 1994 and ran for a decade; joining Space Ghost (secret identity: Tad Ghostal) as director and bandleader, respectively, are former adversaries Moltar and Zorak, whose employment by the intergalactic superhero has no effect on their ill will toward him. The trio interacts with live-action guests via pre-recorded and re-edited interviews, though the talk-show conceit is little more than a jumping off point for petty griping, surrealist tangents, and the occasional ant hunt featuring the animated talent.

Promoting a movie can be a drag for both the film’s stars and the press covering its release. Same goes for TV actors and comedians, as well as the talk show hosts who invite them on to stump for their latest projects. They all know this dance, and do it as required. Which is what made Guy Branum’s live comedy show, Talk Show The Game Show, such a breath of fresh air; the writer-comedian made celebs work for those plugs. []

Before Jack Black and Kyle Gass recorded their first album as Tenacious D—and while Black’s film career was still in the deep-in-the-supporting-cast stages—the duo made a series of short films for HBO. The network then grouped the shorts together into six half-hour episodes, airing them sporadically over the course of three years. Produced by David Cross and Bob Odenkirk, the first shorts were broadcast almost as bonus cuts attached to the third season of Mr. Show. HBO reportedly lost interest in the show after Black and Gass refused to give up their executive producer titles and cede creative control to the network; if that’s true, it may help to explain why HBO cut back on its original order for 10 half-hour installments and then burned off what it had over such a long stretch of time, as if someone kept finding unaired episodes under the couch cushions. []

The foibles of British government, exposed with painful clarity. The show follows a fictional ministry—The Department Of Social Affairs And Citizenship—as it manages to accomplish exactly nothing, but participates in the spin, manipulation, and grandstanding that characterizes the modern political process. It’s bitingly funny and alarmingly prescient—so much so that the it actually predicted a few real-life political kerfuffles in Britain. Peter Capaldi’s Malcolm Tucker is a foul-mouthed spin-doctor who delights in excoriating stupidity. Fortunately for viewers, in DOSAC, that stupidity is everywhere. Despite its general look as a workplace comedy, it’s a complex, intelligent satire of bureaucracy, and it spares no one in its path. Creator Armando Iannucci went on to create Veep for HBO after the success of this show. []

From our list of : It’s no exaggeration to claim that Tim Heidecker and Eric Wareheim have invented a completely new kind of television show: Their Tim And Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!—from that title on down—filters the idea of sketch comedy through public-access TV, Dadaism, and poop jokes. One minute, it’s a commercial parody poking at consumerism, the next a rabid commercial for rentable child clowns, the next a story arc about a kidnapped public-access singer. But every single minute bears the stamp of two really smart minds, unafraid to examine the outermost bounds of acceptability. The surface begs to be scratched, and there’s real artistry to be found underneath. No wonder guest stars (John C. Reilly, Patton Oswalt, David Cross, Zach Galifianakis, Jeff Goldblum, the list goes on) have lined up to join in.

Mark Duplass stars as Brett Pierson, a man struggling to stave off dissatisfaction with his work as a Hollywood sound designer as well as in his relationship with Michelle (Melanie Lynskey). Brett’s wife and the mother of his two children, Michelle can’t manage to reverse her waning sexual attraction to her husband. The Piersons’ quest for greater intimacy is compromised further when Brett’s best friend Alex (co-creator Steve Zissis) and Michelle’s sister Tina (Amanda Peet) are concurrently hit with financial setbacks, prompting them to move in with the Piersons.The under-one-roof log line makes Togetherness sound like an in-development CBS sitcom, but in keeping with the brand, the Duplass brothers have no interest in obvious punchlines and pat resolutions. Togetherness is about the unsettling nature of relationships, how they remain constantly in flux and only have as much stability as the participants choose to project onto them. The show mines similar themes to its contemporaries, exploring how an all-consuming desire for intimacy can curdle into a total aversion to it. But with characters in their late 30s, older, wiser and more settled, Togetherness has a world-weariness Girls could never achieve. Its characters have figured out how to navigate the pitfalls of youth, only to learn that every decade is as booby-trapped as the one preceding it. []

The road to hell is paved with the good intentions of Tom Peters (Tim Heidecker), aspiring entrepreneur and newly minted citizen of Jefferton, the decaying pile of strip malls and buffet restaurants run by a fatuous mayor known only as “The Mayor” (Eric Wareheim). Tom Goes To The Mayor is where Heidecker and Wareheim’s blend of the satirical and the scatological first took root on Adult Swim, the limited-animated launch pad for recurring segments, pet themes, and collaborations that would help build the tracking-lines-and-chroma-key world of Tim And Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!

“‘Restore faith in democracy’? I mean, we couldn’t do that even if we wanted to.” You’d be hard-pressed to find a line of dialogue that better encapsulates any series, let alone one as jam-packed as Veep is with its endless digs, off-color insults, and terribly depressing jokes about our intractable government and the self-serving politicians who run it. Even on the rare occasion when the intentions of Julia Louis-Dreyfus’ Vice President Selina Meyer were good, her hopes for clean jobs or a free Tibet were inevitably sabotaged by her single-minded desire to occupy the highest office in the land. It’s not a rosy view, but as absurd as it sometimes became, Veep’s satire only ever reinforced an irrevocable truth: Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts hilariously. []

If those who can’t do, teach, then it stands to reason that many principals also have stymied ambitions. These school officials must first pay their (union) dues as educators before moving on to administration. But does that ascension fulfill those deferred dreams? That’s one of the central questions of HBO’s Vice Principals, the latest dark comedy from Jody Hill and Danny McBride.In tone and setting, it’s a spiritual sequel to their previous premium-cable outing, the mostly uproarious Eastbound & Down. There’s even a blustering man-child at the center of the story. But while the profanity reliably reaches virtuosic levels, it rarely does so at the cost of more meaningful discussion. What Hill and McBride end up with, after the LSD-laced shenanigans, is as much a meditation on disillusionment with life as it is a clash of would-be titans.Fans of the duo who watched the trailers ahead of the premiere needn’t worry that Vice Principals ignores the first word in its title. The central conflict starts off just as it’s framed in the teasers, complete with Bill Murray cameo. A power vacuum is created when Murray’s principal character steps down to look after his ailing wife, giving his two assistants, Neal Gamby (McBride) and Lee Russell (Walton Goggins), even more reason to plot the other’s demise. Their verbal sparring inspires a lot of raucous laughter, naturally. McBride is a master of profanity, but he’s matched by Goggins, who has an uncanny ability to turn “eat shit” into a four-syllable phrase that nonetheless rolls right off his tongue. []

The quietly great Wyatt Cenac’s Problem Areas managed to cut through the din of online discourse and tentpole-touting late-night shows thanks to its measured approach and host Wyatt Cenac’s dry-as-fuck wit. The HBO series, a kind of documentary and talk-show hybrid, offered something that the talk landscape, for all its many, white male-led options, has been desperately lacking: a discussion centered around facts and grounded by real, lived experiences. Cenac never did anything as flashy as invent a new spokesperson for the tobacco industry or stage a big musical number about restorative justice, but the show did do its research on topics like unions, police shootings, and education. Problem Areas always unearthed even more questions as it sought out solutions, but that didn’t make the show any less intelligent or gratifying. Viewers could take heart in watching communities come together in Michigan to improve upon the school lunch program, while also taking away a valuable lesson about the widespread effects of food insecurity. []

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.