“Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.”

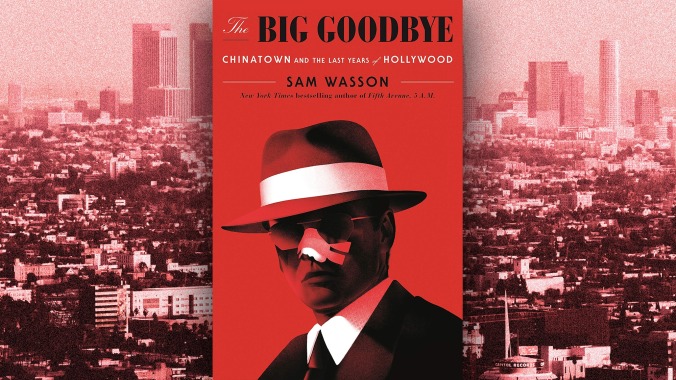

It’s one of cinema’s most enduring lines, the nihilistic coda to one of Hollywood’s most cynical, disturbing, and eternally astounding films: Chinatown. In The Big Goodbye: Chinatown And The Last Years Of Hollywood, cultural historian Sam Wasson swims in the muddy making of the 1974 film, the messy lives of its four main players, and the murky chronicles of L.A.’s studio system and the municipal water wars to produce a page-turner as suspenseful and spellbinding as the Raymond Chandler novel from which the book takes it name.

Robert Towne unhappily squanders away as a script doctor, usually uncredited, for commercial and critical smashes like Bonnie And Clyde and The Godfather. In the wake of the Manson murders, he holes up with three guard dogs, Raymond Chandler’s bloodstained stories, and a history of L.A., all the while dreaming of the impossible screenplay.

As head of production at Paramount Pictures, Robert Evans strings together hit after hit for the studio that all of Hollywood called “the Mountain”: Harold And Maude, Serpico, the first two Godfather films, Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby. He wants Polanski back in the U.S.; he wants Towne’s buzzy, 1937-set script about some detective named J J. “Jake” Gittes; and he’s used to getting what he wants.

Towne punches away at his typewriter with his former roommate in mind, a character actor starving for the role that would make him a star: Jack Nicholson, a skirt-chasing popinjay his circle of friends nicknamed “the Weaver,” for his stream-of-consciousness story spinning. Back when they shared an apartment, Towne remembered Nicholson perched at the mirror, telling himself, “Look at my perfect teardrop nostrils.”

In Chandleresque fashion, there was also a dame involved. And in Wasson’s telling, Faye Dunaway, like the most memorable hard-boiled heroines, existed only to obfuscate. Playing the wealthy and recently widowed Evelyn Cross Mulwray, Dunaway goes full Method, exasperating and porcelain brittle. The crew responded in kind, name-shaming (“The Dread Dunaway”) and rumor-mongering (“Didja hear Faye refuses to flush her own toilet?”).

But it was the men, of course, who were the true monsters. “This is a book about Chinatowns,” Wasson writes, the Chinatowns that are the lives of his four protagonists. Polanski is emotionally and physically abusive on set, especially toward Dunaway. He continually quarrels with Towne, and, perhaps triggered by his wife’s murder, rewrites the script so that the blonde heroine brutally dies in the end (while the screenwriter insisted on subverting noir norms with a happy ending).

Nicholson, Evans, and Towne come off as Hollywood Hills heathens who surround themselves with mountains of cocaine and self-destruct to various degrees. Nicholson chooses eternal bachelorhood over settling down with starlet supreme Anjelica Huston, whose legendary director and screenwriter father, John, played Chinatown’s villain. Towne wins the film’s only Academy Award—embarrassed that the film lost in 10 other categories, he hides the Oscar between his limo’s seats—and, a decade later, writes and signs on to direct a sequel. Days before initial shooting, fried on drugs and divorce proceedings, he dissolves into a paranoid wreck, and is found hiding, fetal-positioned, under a couch. Evans—one of the many kings of the Hollywood coke mountain—fritters away his home, fortune, and career following a cocaine-trafficking conviction. But the three remain close friends, even with Polanski, self-exiled from the U.S. on rape charges since 1978, facing extradition.

In 1990, flush with Batman cash and studio-system goodwill, Nicholson eventually directs that long-festering sequel, The Two Jakes, a convoluted rehash that substitutes oil for water. That film’s icy reception buried plans for a third film in Towne’s planned Los Angeles saga, Gittes Vs. Gittes, which would have focused on the privatization of the city’s public transportation network (internet speculation posits that Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, intentionally or not, completed the trilogy). Coming as no surprise in this remake era, news recently dropped that a Chinatown prequel series, scripted by Towne and David Fincher, is in early development at Netflix.

Why are we, like Jake, unable to forget Chinatown? Wasson doesn’t say. Perhaps an answer lies in those final lines. When pitching his script around Hollywood back in the early ’70s, Towne kept mostly coy about what the film was about. Chinatown is “a feeling,” he told Evans and Nicholson, “a state of mind.” In an immediate post-Manson, post-Watergate, post-Vietnam America, Chinatown combined two narrative tropes, the noir and the conspiracy thriller, to pile on the paranoiac dread. In Chinatown, the shadows have shadows.

Today, films go out of their way to explain the unexplainable. Seen The Big Short? Consider yourself an expert on the 2008 financial crisis. But watch Chinatown 10 times, and the water rights plot, with its riverine twists, turns, and incest subplot, and you’ll likely come out confused after every viewing. Just ask Jake Gittes, who, at film’s end, mumbles what we all know to be true about this world and our place in it: “As little as possible.”