The biopic Big Eyes adds another misfit to Tim Burton’s gallery

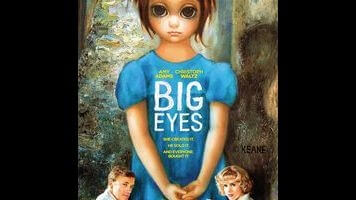

Tim Burton reserves a special place in his heart for hucksters. On the rare occasion that the filmmaker behind Alice In Wonderland and Sleepy Hollow strays from the path of making baroque blockbusters out of preexisting properties, it’s usually to celebrate the moxie of some real or fictional fabulist: Ed Wood, the “worst director of all time,” whose zealous ambition Burton treated as more important than his ineptitude, or the incorrigible fibber of Big Fish, that “heartwarming” tale of a family man who bullshits his wife and kids for an entire lifetime. There’s a little bit of both those characters in Walter Keane, the real-life figure Christoph Waltz plays in Burton’s new movie, Big Eyes. The modern artist as celebrity gadfly, Keane made a fortune in the ’50s and ’60s selling paintings of adorable moppets with oversized peepers, whose maudlin appeal enraged art critics. Keane was a relentless self-promoter, goosing interest in his work through outrageous public behavior, and a savvy businessman, building an empire on the shrewd decision to mass produce prints of the paintings. He was also, as it turns out, a complete charlatan: The real artist was his wife, Margaret, who toiled away in secret, painting one saucer-eyed waif after another, each of which Walter would claim as his own.

It’s not difficult to see what drew Burton to this material. Keane is a fascinating fraud, a pathological liar who leeched off the talent of others and used charm to conceal his total lack of scruples. Waltz attacks the role with unrestrained gusto, to the extent that it’s difficult to say if he’s delivered a great performance or a terrible one. (Though playing a man born and raised in Nebraska, the actor makes no attempt to mask his accent—a choice that can be attributed to laziness, a sly nod to Keane’s fundamental phoniness, or both.) The problem with Big Eyes, as it’s been conceived anyway, is that it isn’t really about Walter; instead the film’s focus is on Margaret (Amy Adams), the real victim of his two-decade con job. That’s an understandable and even noble approach: Margaret was, after all, the one with the gifts, and the story of her husband bilking her out of success is sad and enraging. What it’s not, however, is especially cinematic, and the movie ultimately amounts to watching someone stew passively on the sidelines of her own life, until the time comes for a very belated reckoning.

That’s not to say that Big Eyes is a wash, exactly. There is, in fact, some fun to be had with its vision of mid-century San Francisco, where an ambitious hack like Keane could infiltrate the art world through the force of his snake-charmer personality. Freed from the duty of Gothic world building, Burton seems liberated by the opportunity to operate in some version of reality—though, admittedly, his take on the Bay Area bears a certain resemblance to the fairytale suburbia of Edward Scissorhands. The director coats every scene in a gauzy glow, a sentimental aesthetic that, while somewhat unsightly, suits this tale of a culture hijacked by the big profits of kitsch. Burton also can’t quite resist indulging in a couple of fantasy sequences, as when Margaret mentally supplies everyone at the supermarket with her eerie ocular signature. More distracting is the script’s employment of a totally superfluous narrator—a journalist played by Danny Huston, whose expository musings feel like the handiwork of executive producer/distributor Harvey Weinstein, who never met a movie to which he couldn’t affix some unnecessary voice-over.

Big Eyes has plenty of surface pleasures, but there was reason to expect more than that from it. After all, the film reunites Burton with screenwriters Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, the team that wrote his masterpiece, Ed Wood. Here, though, the duo have fashioned a much squarer biopic, one built around an injustice of sexism and deceit that’s difficult to dramatize. Margaret spends much of the film retreating to her secret studio, a dimly lit sweatshop that Walter guards with Bluebeard-like diligence. Perhaps fearful that their heroine will come across as a doormat, Alexander and Karaszewski supply her with a steady stream of withering putdowns, but it’s still dispiriting to see Adams, an actress who radiates vitality, reduced to playing a stifled, long-suffering wallflower. And it’s not as though the film has many big opinions about her iconic art or what it meant to her.

Gunning for some redemptive uplift, Big Eyes builds inevitably to a climactic courtroom standoff, the rousing details of which are apparently true. Even here, though, when Margaret is finally granted some agency and respect, the film can’t help but be seduced by Walter, whose comic attempts to serve as his own defense attorney—running back and forth to question himself on the witness stand, like a character in a Jim Carrey movie—end up taking precedence. The film’s sympathies may lie with the aggrieved party, but Burton, that longtime lover of misfits, clearly has big eyes for another.