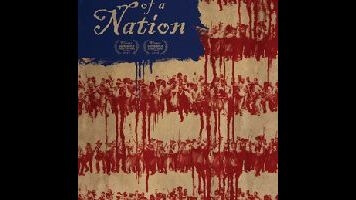

From the moment Nate Parker revealed the title of his fiery directorial debut, The Birth Of A Nation has been treated like more than just a movie. This dramatization of the life and death of Nat Turner, the black preacher who led an 1831 slave insurrection in Virginia, earned its first standing ovation at Sundance in January, before a single frame had even rolled. Was the audience at that packed gala premiere preemptively cheering its very existence, at a time when the reverberations of America’s ugly racial history were making daily headlines and when the movie industry—particularly that annual pageant of self-love, the Oscars—was taking some deserved heat for its lack of diversity? Parker’s hard-won, well-publicized efforts to get the project off the ground seemed to bestow instant essentiality upon it, shielding it from criticism. Then some awful allegations from his past resurfaced, turning a difficult movie to question into a difficult one to endorse. There are now those who refuse to even see The Birth Of A Nation, because doing so would support the man who made it.

Separating all this context, controversy, and conversation from the actual film it surrounds isn’t easy. But Parker, the director-writer-producer-star, removed the film from a vacuum the minute he borrowed the name of D.W. Griffith’s 1915 classic, a movie every bit as cinematically influential as it is horrifically racist. The choice of title was a gauntlet dropped to the dirt, a bold declaration that his Birth Of A Nation would reclaim the history distorted by Hollywood’s very first blockbuster, while also offering a different turning point for the country, tracing the ongoing battle for black lives straight back to a single spark of rebellion. That ambition eclipses Parker’s means, both creative and monetary: He’s delivered a passionate but sometimes clumsy historical drama. At the same time, the power of seeing this story—a slavery narrative of not just suffering, but also resistance—put up on screens helps compensate for the first-feature flaws.

A biopic conventional in all but the biography it depicts, The Birth Of A Nation draws much of its gravity from the details of its true story. It begins with Nat as a young boy (Tony Espinosa), raised on the Turner plantation in South Hampton County, side-by-side with the white child, Samuel, who will eventually call him property. Two parental figures shape his future: His father, Isaac (Dwight Henry), whose flight from the plantation after killing a white man in self-defense provides Nat his first glimpse of rebellion; and Elizabeth (Penelope Ann Miller), wife of the master, who encourages Nat’s learning to read and introduces him to the Christian faith that will become his calling.

It’s when The Birth Of A Nation leaps forward to Nat’s adulthood that Parker takes over the role. Casting himself turns out to be his best choice as a filmmaker: Having made strong impressions in Red Tails and Beyond The Lights, he delivers a performance here of slow-simmering conviction; we can see the will to resist developing behind Turner’s eyes, a quiet storm building scene by scene. Nat now belongs to the grown-up Samuel (Armie Hammer), who joins Benedict Cumberbatch’s character in 12 Years A Slave on the list of slavers whose (very relative) decency has its plain limits. Nat has learned how to flatter Samuel’s pride and sense of moral self-regard, and he uses that information to secure small comforts, as well as to arrange the (again relative) wellbeing of Cherry (Aja Naomi King), the woman who will become his wife. The Birth Of A Nation handles their furtive, restricted courtship with quiet tenderness—a nice counterbalance to the film’s more bombastic touches.

Parker, who co-wrote the heavily researched screenplay with Jean McGianni Celestin, synthesizes the available information into a tale of moral awakening. Nat is eventually charged with bringing the gospel to other slaves, and as he navigates the plantation system, Parker silently, reactively expresses how the young man absorbed the suffering around him and converted it into an imperative. (In one of the film’s most crucial and gut-wrenching scenes, Turner helplessly witnesses a particularly cruel plantation owner mutilate and force feed one of his field hands, who’s refused to eat in protest.) At its most poignant, The Birth Of A Nation underlines the religious dimension of Turner’s eventual decisions—the way his insurrection grew out a sense of spiritual responsibility. Samuel and the other masters want Nat to teach subservience through his sermons; they’ve perverted Christianity into another arm of their oppressive industry. But what Nat increasingly finds in the good book reads more like an encouragement to fight than a command to kneel.

Since premiering the film at Sundance, Parker has made small tweaks to The Birth Of A Nation, the most productive of which is the complete abandonment of his cheesiest visual idea: the conception of Turner’s ancestors, glimpsed in dreams and visions, as Star Wars-style hologram specters. But not all of the problems could be so easily excised. In its worst moments, The Birth Of A Nation gains the faint impression of bad community theater, as some of the actors—including Miller as the picture of Southern ladyhood and Mark Boone Junior as a charlatan reverend—grapple awkwardly with their courtly dialogue. Parker’s direction of the camera is similarly inconsistent: While there are several striking, poetic images (blood erupting from a husk of corn; Turner leaning over a literal fire as a figurative one wells up inside him) the film also has an inexpressive, digital flatness that works against the immersive qualities of its antebellum period detail. This is very much a debut feature, a passion project from an enthusiastic director still learning the craft.

More detrimentally, The Birth Of A Nation loses its footing in the final act, when it should be ballooning with dramatic intensity. The film builds up a proper head of righteous steam, pivoting the rebellion at least partially around Nat’s curdling relationship with Samuel, who shows his true colors when he viciously whips his favored slave for baptizing a white man and—in a plot development that gels uncomfortably with the allegations against Parker—allows his guests the “right” to rape the female slaves. But once the overthrow finally arrives, it seems to pass in a blur of montage, Parker “tastefully” condensing these scenes of violence into suggestive, illustrative bursts. After the slow accumulation of horrific detail that precedes it, this closing action feels like an afterthought—a disappointingly rushed, abbreviated take on a famous act of defiance. It should have filled an hour of gripping runtime.

Structurally and stylistically, The Birth Of A Nation doesn’t deviate much from the template set by countless Hollywood epics: Parker isn’t immune to the sentimental appeal of swelling music, slow-motion, or scores settled on the battlefield, and his finale—powerful though it is—bears an unmistakable resemblance to the ending of Braveheart. (Mel Gibson, of course, would never set one of his own grueling depictions of bodily harm to a soundtrack selection as affecting as “Strange Fruit.”) In a way, though, the film’s mainstream squareness feels significant. Parker is addressing a long-standing oversight in representation, applying a common cinematic language to a crucial history lesson that Hollywood has never touched. He’s giving a different audience, an underrepresented one, the conventionally stirring prestige drama white audiences take completely for granted, the same way that black filmmakers in the ’70s put their own spin on the boilerplate genre flicks of that era. Maybe all great American icons, especially the ones that still make America nervous, deserve their own middlebrow biopics. Nate Parker’s film on Nat Turner, imperfect though it is, deserves to be seen.