In the universe of The Borgias, trust is an almost impossible concept for anyone to hold onto. With Italy caught between the feuding countries of France and Spain, the whole of its countryside full of rival city-states, and Rome itself existing in an eternal tug-of-war between the Vatican and the Roman noble houses, any alliance made lasts only as long as it’s convenient for one of the parties involved. Everyone has an ambition, a price and a grudge, and those considered indispensable one day can be cast aside the next. Small wonder that Alexander has impressed upon his children since day one the importance of familial loyalty above all else, and small wonder that the pressures of that loyalty have driven his children to commit such sins as fratricide and incest.

This distrustful atmosphere is of course a large part what keeps The Borgias so consistently entertaining. While at times it’s difficult to keep the various feuding factions and city-states separate without a map of Renaissance Italy handy, the rate at which allegiances change mean that aside from the major figures—Alexander, Caterina, della Rovere, Savonarola—the sands are shifting so much that keeping a chart of who’s on what side is irrelevant. One rumor or one purse of gold, and you’re moved from one camp to the next as easily as Cesare reorganized the seating chart of his sister’s wedding into battle lines. “The Banquet Of Chestnuts” is a lively example of this culture of backstabbing and escalation, showing both the cost it takes to keep these alliances alive and the ease by which they can be broken.

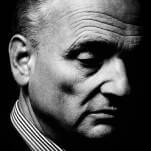

And it comes at a point where by all rights Alexander should be enjoying a position of relative strength. Having successfully emptied the consistory of cardinals he deemed a threat, he has now stocked the bench with individuals he considers pliant, regardless of their relative experience levels. (“Their only duty is loyalty to us. The rest they can learn as they go along,” he says to Cesare in the usual disinterested tone he has for day-to-day business matters.) One of those new cardinals is Giulia’s brother Alessandro, whose earned his red robes as part of his sister’s quasi-alimony payment from Alexander and came to the consistory with the promise of a head for figures. Only it doesn’t seem that he’s as clever as advertised, as Cardinal Sforza quickly overwhelms him with books his first day—shades of Norville Barnes early in The Hudsucker Proxy—and Giulia swoops in to assist him, retaking her old role from “Paolo” as Vatican auditor.

Alexander doesn’t take long to see recognize Giulia’s handwriting amidst her brother’s audits, and he has her dragged from her house by the papal guard, a move that would have been out of character even half a season ago but now is par for the course. Since the various attempts on his life Alexander doesn’t seem to have lost his facilities—witness how with one grand speech he manages to convert a Venetian complaint of piracy into an excuse for a crusade and all the attendant taxation—but there’s been a definite sense that the endless scheming has taken its toll on him. His speech is now even more willing to indulge in grandiose metaphors, seeing conspiracies all around him, and even a gesture as seemingly innocent as this only serves to remind him his inquisition was a temporary solution. “New cardinals become old cardinals…The plotting, the scheming, I can see it all as inevitable as the tide.”

Giulia’s idea to fix this problem is nothing short of masterful: the Banquet of Chestnuts, a grand event held for all the cardinals which swiftly devolves into an orgy rife with blackmail opportunity. Beyond political scheming, one of The Borgias’ greatest strengths is its gleeful willingness to depict sinful behavior amidst the holiest of settings, and the degree of blasphemy here is elaborate on a new scale. Director Jon Amiel casts the entire scene in a dark and unholy light, prostitutes dressed as nuns gradually removing their vestments as Giulia plays auctioneer with gusto, driving the cardinals into a bidding frenzy and pushing them to ever more reprehensible behaviors. The scene is made all the better with the welcome return of Simon McBurney as the Vatican chronicler Johannes Burchard, a voice-over of his report playing against the decadence of the banquet, describing the events in wonderfully clinical terms: “It is my sad duty to report that the said habits did not remain on the comely maidens long beyond the first course. They flaunted their nakedness for the cardinals with the abandon for which Roman prostitutes are noted.”

This gets Alexander what he wants—in a wonderful scene for Jeremy Irons, feigning outrage at the official report in front of the whole sheepish consistory—but I’m more interested in what this gets Giulia. She intercepts her brother prior to the evening and gives him instruction to stay away, a move which could be dismissed as looking out for your sibling were it to happen on any other show. But here, it plays more as an insurance policy, leaving one cardinal who’s not compromised and who’s already proven to be pliant to his much smarter sister’s needs. The show has always struggled to give Lotte Verbeek enough to do, and while I doubt they’ll be putting her into direct conflict with Alexander, this strikes me as a move that could pay dividends down the road.

Speaking of sibling interactions full of hidden meaning, now that “Siblings” has finally resolved the sexual chemistry between Cesare and Lucrezia, the focus now shifts to dealing with the repercussions. Thankfully, we were spared a clichéd morning after scene of the two waking up in the same bed together, and are given a much more discomforting one where Alexander praises the “blushing bride” as Cesare and Lucrezia exchange loaded glances over his shoulder. Less amused is Ferdinand, who tries to coax stories of his cousin’s deflowering only to be put off by Alfonso’s sheepish comments about how she liked it “the usual way.” Ferdinand demands the marriage be consummated, and—never missing an opportunity to remind the Borgia family he doesn’t consider them his masters—also demands that it be witnessed by members of both families.

Alexander’s forced to acknowledge the action as a necessity—“There is a precedent” he weakly tells Cesare—but his children aren’t nearly as sanguine. And it’s here we see the ramifications of what the two did together, a temporary bandage on their pain that when ripped off has left even deeper wounds. Lucrezia goes from stunned disbelief to raw emotional rage, screaming at her brother that he has lost all love and honor for her, and then adding insult to injury by asking him to bear witness. And Cesare’s vaunted powers of control are shed with increasingly terrified and desperate glances as he fears the secret may come out—for the first time, he’s resembling the weakness of his brother Juan. There’s emotions subtle and broad in this fallout, and both François Arnaud and Holliday Grainger sell every beat they’re asked to play.

The official consummation plays out in an affair more spartan than Giulia’s banquet—one bed in the center of the room, Ferdinand and Cesare looking on behind curtains—and despite its businesslike arrangement it’s strikingly intimate. Lucrezia instructs Alfonso to disregard their audience and to look into her eyes, but it’s her brother she’s making eye contact with, cutting back and forth between the two as she reaches orgasm. And Cesare’s look carries similar arousal, a barely restrained gasp shadowed overwhelmingly by the look of a man who realizes that he’s damned.

Amidst all of this it seems like Alexander’s the only one not having sex, or at least not until he gets an unexpected visitor: Bianca, formerly Alexander’s favorite prostitute and now the wife of Lord Gonzaga. Alexander allied with Gonzaga to crush the French armies in last season’s “Stray Dogs,” and in one of his own most sacrilegious acts, took Bianca to bed the night before her husband marched off to war. And now that’s coming back to bite him, as Caterina Sforza’s spies have given her the information of these trysts, and passed it onto the duke to persuade him to join their conspiracy. In a nicely Shakespearean gesture Rufio leads Gonzaga to spy outside the Vatican during this twist, and twists the verbal knife as well as he does the actual one: “Knowing this pope, I’d say he’s entering your wife… just about… now.”

The move is both a nice payoff to a thread the writers could have abandoned—proving that while this world may be confusing at times to viewers Neil Jordan knows what he’s doing—and one that turns the tables on Alexander nicely. In one fell swoop by Gonzaga the pope’s new position of moral authority amongst his new cardinals is publicly undermined, and an ally previously considered too self-consciously noble to be a threat is now a potentially dangerous enemy. Because that’s how things play in the world of The Borgias: plan ahead all you like, but eventually someone grabs you by the chestnuts.

Stray observations:

- Cardinal Versucci goes on a pilgrimage, spreading the various titles and deeds he stole across Italy’s convents and monasteries until Micheletto finally catches up to him. Vernon Dobtcheff’s been with the show since the beginning, less prominent amongst the cardinals as Sforza or della Rovere but a solid representative of the duplicitous consistory Alexander had to work with. And while there’s less investment in his story as there is in the Roman scheming, it’s nice to see the character end on a redemptive note, quietly slitting his wrists as a final middle finger to a pope who used him from the beginning.

- Once again, Alexander shows his disinterest in someone requesting his audience by paying more attention to his grandson. I particularly enjoyed his dismissal of the Venetian attempts to connect their turmoil to Rome: “Well, we thank you for bringing our suffering to our attention. We are not aware.”

- Amiel regularly uses the cross-cutting technique to great effect in the episodes he directs, and it’s used well here to switch between Giulia’s outlining of the banquet scheme to Alexander and Caterina outlining Gonzaga’s new commitment to their conspiracy. It nicely builds anticipation for the acts of blackmail to come.

- Alfonso and Lucrezia’s conversation where she gently rebuffs his advances is hilarious: “Maybe our love has to be more of the soul.” “Like brother and sister.” “No. Not like that.”

- “You may tell your father the manner has been dealt with to my satisfaction.” “And you may get out of my house.” If Ferdinand survives to the end of this season it’ll be a minor miracle.