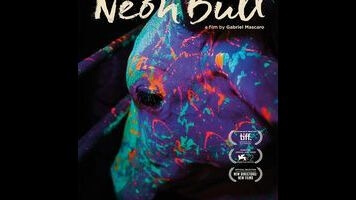

American movies about the rodeo—most of the notable examples, from Sam Peckinpah’s Junior Bonner to Sydney Pollack’s The Electric Horseman, were made in the ’70s—invariably feature a performer as the protagonist. Neon Bull, a Brazilian film with a similar setting, focuses instead on the grunts who toil behind the scenes, dealing with literal bullshit. The sport in question, vaquejada, is popular in the Nordeste region of the country; it consists of two men on horseback flanking a running bull and attempting to trip the animal at a designated spot. (Judging from this film, the task doesn’t appear all that difficult—nobody is ever seen to fail, at least—but presumably there’s considerable skill involved.) While the vaqueiros get all the glory, however, it’s up to various low-wage workers to feed and transport the bulls, get them in place for the competition, and dust their tails with chalk, for roughly the same reason that a pool player chalks a cue. Writer-director Gabriel Mascaro doesn’t really have a story to tell about these folks, but he does have a wealth of almost documentary-style detail to share, plus style to burn, and that’s nearly enough.

For Iremar (Juliano Cazarré), the vaquejada life is something to be stoically endured while he entertains dreams of the profession he’d really like to join: fashion design. During downtime, Iremar steals a porn magazine from a co-worker (nobody here has a smartphone, much less a laptop) and sketches outfits onto the naked women; after an event, he collects hair stripped from bulls’ tails, which he later spray-paints gold and fashions into a dancer’s costume. The dancer in question appears to be Galega (Maeve Jinkings, from Neighboring Sounds), though neither her function in the organization nor her relationship to Iremar is entirely clear. Iremar definitely isn’t the father of Galega’s young daughter, who bears the unfortunate-to-English-speakers name Cacá (Alyne Santana), but he does nonetheless seem to have paternal feelings toward her, often letting her hang around while he works at both his job and his hobby. And that’s about all there is to relate in the way of a narrative, as nothing much ever really “happens.”

Instead, Mascaro uses this milieu, and his off-center approach to it, as an excuse to generate as many stunning and/or startling images as he can. From the very first shot—which looks downright surreal, and is eventually decipherable as one bull’s haunches smooshing another bull’s head—Neon Bull privileges oddity for its own sake, which is invigorating until such time as it starts to seem like a dead end. There is indeed a neon bull, for example, never explained, and the film pauses for multiple interludes that see a figure perform in a spotlight for an unknown audience. Even Iremar’s passion for fashion, in this intensely macho context, feels like a deliberate effort to avoid the expected. Combined with the overall plotlessness, this eventually gets a bit oppressive, with the nadir being an extended sex scene between Iremar and a hugely pregnant woman that Mascaro evidently included with no greater purpose than to explore what a hugely pregnant woman looks like having sex. (Also, if you ever wondered what a horse being masturbated to orgasm looks like, wonder no more.) Still, there’s considerable talent on view here, even if it’s mostly expended on local color, incidental moments, and random weirdness. Maybe Mascaro should try grabbing the horns next time, rather than the tail.