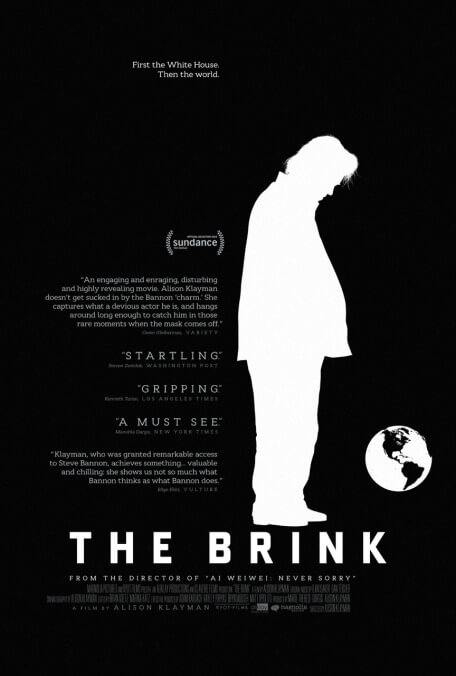

Steve Bannon loves nothing more than being the center of attention, even if that involves boos and hisses. Fortunately for him, filmmakers are practically lining up to oblige. Errol Morris couldn’t find a U.S. distributor for his feature-length interview, American Dharma, which premiered at Venice last year; he’s apparently now planning to release the film himself, in the hope that viewers will ignore those critics who complained (incorrectly) that he treated Bannon with kid gloves. In the meantime, there’s Alison Klayman’s The Brink, which follows Bannon over the course of roughly a year—starting when Trump fired him from his position as White House Chief Strategist and concluding with the 2018 midterm election—as he travels across the U.S. and all over Europe, attempting to unite various right-wing campaigns around a brand of populism that he terms “economic nationalism.” The inherent risk of this vérité approach is that your subject won’t prove to be all that fascinating, and The Brink, while far more openly critical of Bannon than American Dharma, ultimately offers little justification for spending an hour and a half in his company.

Part of the problem is that Bannon and everyone he talks to—from former UKIP head Nigel Farage to Blackwater founder Erik Prince—is very much aware that Klayman doesn’t share their agenda, and that too much candor could get them in trouble. Prince actually stops mid-sentence at one point, having suddenly remembered that he’s being filmed; “This is on camera,” he tells Bannon, “so I’ll be careful.” Needless to say, his original thought doesn’t get continued, at least that we see. Other omissions are less blatant but no less troubling. After Bannon’s effort to get accused child molester Roy Moore elected to the Alabama Senate fails, onscreen text notes that he was fired from Breitbart, lost a radio show he’d been hosting, and was cut off by billionaire donors Robert and Rebekah Mercer. If Klayman asked him about these enormous setbacks, however, none of that footage made it into the film. We just get a minute or so of Bannon silently pacing a room, looking anxious (footage that could have been shot at any time), and then it’s on to the next speaking engagement or strategy meeting. It’s not that Bannon never gets challenged—several journalists (mostly from the U.K.) push back hard against his nonsense. But Klayman seems leery of saying or doing anything that might potentially make him uncomfortable.

The key difference between American Dharma and The Brink in this respect is instructive. Bannon spends a lot of the former talking about his favorite movies, and Morris undermines his delusions of grandeur by visually indulging his inane cinematic fantasies, even conducting the interview in a replica of Twelve O’Clock High’s Quonset hut. That’s too subtle and artful for Klayman, who editorializes by reminding viewers of such major news events as the Tree Of Life synagogue shooting and the record number of women and people of color elected to Congress (almost exclusively as Democrats) last November. This sort of gotcha journalism is better suited to brief cable-news segments and late-night quasi-comedy bits. Those of us who despise Bannon require no convincing that his rhetoric is destructive, and are well aware of his failures. Those who admire him won’t be persuaded, and are unlikely to seek out this film in any case.

Ultimately, The Brink’s value lies not in any argument it makes, but in how much unfiltered Steve Bannon it captures. Here, the relevant comparison is to The War Room, and what we see of Bannon is a bit like James Carville’s cutthroat ethos as expressed through the comparatively placid persona of George Stephanopoulos. In public appearances, he mostly reassures people who hate immigrants that they aren’t racist; audiences eagerly embrace the message but don’t seem especially galvanized by his limp oratory. And the “private” Bannon, insofar as he exists on screen, is downright boring, unless you’re really into self-deprecating remarks about his schlumpy appearance. Klayman has so little compelling candid footage to work with that she includes some truly trivial observations, like Bannon’s penchant for placing a woman between himself and another man at photo ops (“A rose between two thorns,” he says every time—a canned line, but every public figure has a bunch of those), or his good-natured resistance when Klayman tells him how a Chinese name should actually be pronounced. We learn almost nothing about his tenure at Breitbart, but do get to watch him look through old yearbook pictures, remarking on how handsome he once was. The Brink winds up being neither expository nor revelatory. It’s just sort of there, tacitly acknowledging (especially when it travels to Venice for the Dharma premiere!) that every move Steve Bannon makes merits our genuflection or our concern. Arguably, its ideal viewer is Bannon himself.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.