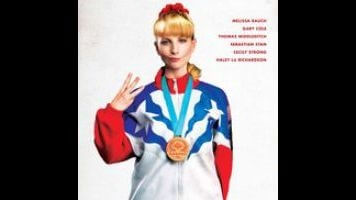

The Bronze follows a clear template: It’s an inappropriate-mentor comedy, pairing a foulmouthed adult with an innocent younger person, just like Bad Santa, Bad Words, and plenty of others before it. Given those easy comparisons, it takes a surprising amount of time to adjust to the film’s shticky conception of its main character, Hope Ann Greggory (Melissa Rauch). Hope is a former gymnast and one-time America’s sweetheart known for persevering through an injury and winning a bronze medal at what the movie is clearly legally prohibited from calling the Olympics. But following her emotional triumph, Hope was unable to fully recover to compete again—and gymnastics, being a young and tiny person’s game, passed her by. The movie rejoins her as an adult, still living with her father in her hometown of Amherst, Ohio, and exploiting her local-celebrity status by demanding free food from the Sbarro at the mall.

Hope speaks, in her nasal Midwestern twang, with the kind of elaborate, relentless vulgarity that comedy writers love (particularly if they’ve seen Bad Santa a few dozen times). She makes no real concession to the town’s rose-colored vision of her, and no one in Amherst seems to take particular notice of her cruelty, with the exception of her patient, long-suffering father Stan (Gary Cole). Even for the hero of an inappropriate-mentor comedy, the diminutive, short-fused Hope acts and looks like a cartoon, complete with an ever-present neck-hugging trainer jacket that manages to make her look even smaller than she is (she wears it, at least in part, to hide the physical developments that helped curtail her career).

The idea of a chipper gymnast gone to seed is funny, to be sure—and so funny to Rauch (who co-wrote the movie with her husband Winston) and director Bryan Buckley that they don’t feel the need to draw a clean line between Hope’s childhood pep and her current, degraded state. For example, if Hope cares so much about her heroic image, why isn’t her bad behavior a little more subtle or passive-aggressive? The real answer, of course, is that the movie needs Hope to say outrageous, offensive things so it can bask in the shock-comedy effects. But after a protracted adjustment period, Hope does come into focus. The character makes the most sense as a woman who has stalled out in the hormonal surliness phase of her bygone teenage years—and The Bronze makes the most sense as a faux-outrageous comedy that sometimes more closely resembles an actual psychological drama.

The movie also gets a surprising amount of mileage from its resemblance to a real sports movie when Hope takes to coaching new local hero Maggie Townsend (Haley Lu Richardson) for plot reasons that might be described as overelaborate. At first, Hope gives Maggie an amusingly destructive regimen of napping, snacking, and blasting Avril Lavigne (another nicely detailed sign of Hope’s arrested-teenager status, along with her constant Fanta-sipping). But eventually, she warms to the job and to Maggie—and to Ben (Thomas Middleditch), the low-key guy from her past who co-runs the gym where she and Maggie practice. The developing relationship between Ben, who Hope calls “Twitchy” after his physical tics (which she mis-classifies as “deformities”), makes very little sense—and becomes, against the odds, kind of touching for its very unlikelihood.

That’s true of the rest of Hope’s obligatory softening, too. It comes as no surprise that this character must eventually begin to move past her vulgar hostility (or at least her hostility). But the earliest signals of her potential decency have a certain delicacy about them: She treats the mangy regulars at her local mall with a plainspoken friendliness, and she is fiercely anti-littering, part of a protective instinct toward the dinky little town she calls home. Rauch goes after plenty of easy laughs throughout the movie, and gets some of them. But she’s more affecting when chasing her surliness with moments of humanity.

Her believability in the serious moments neutralize the fact that The Bronze is only hit-and-miss as a comedy, leaning heavily on the verbal (which is to say: swears). The gym setting offers a natural proscenium for physical gags, but Buckley doesn’t really frame for comedy—and there’s no discernible logic, comic or otherwise, for his random cuts to wide shots mid-scene. The best shot in the movie isn’t comic at all, but rather a slow track across the gymnastics floor, past Maggie’s routine, zeroing in on Hope’s pensive face. At this point, if not much earlier, anyone looking for a truly blackhearted, merciless comedy will be disappointed. But that can be a zero-sum game; at least The Bronze softens up convincingly.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)